Well, I’ve joined a delightful group of people on Twitter and we’re engaged in a read-along of The Wind in the Willows. As you know, it’s one of my favourite books of all time, and a couple of years ago I produced some of my best recent articles surrounding my favourite chapters.

We’ve now reached Chapter VI and, as I already mentioned when talking about The Open Road, I’m not very fond of the character of Toad, and I’ve got a lot of reasons, some rational and some less so.

First of all, I’m all for a rascal as a main character but I don’t like the lack of accountability that seems to come with Toad. Grahame seems to think Toad’s imprisonment isn’t fair, and he depicts it as some sort of social injustice, where the accursed amphibian was behaving like a bully and using his money to wreak havoc on the innocent countryside.

Another reason I don’t like Toad has its roots in the genesis of these chapters.

Grahame wrote the book for (and a lot of times with) his son Alistair, but these particular chapters date back to a time when the relationship with his son had started to deteriorate. Alistair is often complaining his parents don’t come to visit him, and he reached a point where he changed his name to Robinson as a provocation for his father (Robinson was the name of the guy who tried to shoot him back in 1903).

Lots of biographers, from Alison Prince to Humphrey Carpenter, have speculated that Kenneth’s writings on Toad’s excesses were a way to patronise Alistair. Maybe that’s what I’m picking up when I instinctively dislike Toad so much. I loathe patronising writing.

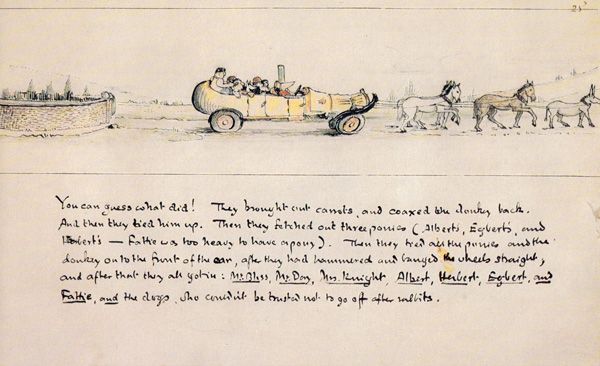

I do love, however, this illustration by Richard Johnson with Toad pretending to be driving his motor.

…he would arrange bedroom chairs in rude resemblance of a motor-car and would crouch on the foremost of them, bent forward and staring fixedly ahead, making uncouth and ghastly noises, till the climax was reached, when, turning a complete somersault, he would lie prostrate amidst the ruins of the chairs, apparently satisfied for the moment.

What about Toad, then?

Well, I come here neither to bury Toad nor to praise him. I have no interest in writing an article on why I dislike something. I prefer to focus on some interesting aspects of the chapter and make something nice out of it. So I’ve decided to talk about Toad’s car.

Grahame has a striking anti-industrial mentality, something that strongly ties him to Tolkien, and when dealing with Toad’s car he employs a couple of narrative tricks.

The first one is ridicule by exaggeration: when describing Toad’s attitude and attire, we’re drawn to believe Toad fancies himself a modern knight on his noble steed, in a very quixotic way, and his attire reflects his delusion: his “singularly hideous habiliments”, as Graham puts it, “transform him from a (comparatively) good-looking Toad into an Object which throws any decent-minded animal that comes across it into a violent fit”.

The very word “habiliments“, according to Annie Gauger in her excellent annotated edition, is a voluntary archaism: a version of the words appear in Sir Thomas Malory’s 1470s Morte d’Arthur, and in Raoul Lefévre‘s Histoire de Jason the word is specifically used to describe the vestiments of a chevalier:

Hauyng the forme and habylement of a knight.

It’s only natural that the word comes from the Old French habillement, and we still find it in the Italian very common “abbigliamento”, simply meaning “clothing”.

Grahame’s attitude towards technology is also conveyed through another trick: random capitalization. According to Gauger, the capitalization follows the Gothic style and it’s meant to convey how something familiar can be transformed into an Object of horror, into something that looms over humanity with its menacing shadow.

You’ll recognise a similar approach in Tolkien’s description of Saruman’s madness:

To take the more obvious example first, Saruman shows many signs of being equatable with industrialism, or technology. His very name means something of the sort. Searu in Old English (the West Saxon form of Mercian *saru) means ‘Device, design, contrivance, art’. Bosworth-Toller’s Dictionary says cautiously that often you cannot tell ‘whether the word is used with a good or with a bad meaning’.

— Tom Shippey. The Road to Middle-earth: How J. R. R. Tolkien created a new mythology

Toad’s ridiculous attire rarely gets illustrated properly, as many artists decide to represent faithfully what might have been the clothing of a bourgeoise “motorcarist” at the beginning of the last century. On the historical context surrounding the motorcar phenomenon, take a look at this excellent article.

What about the car?

As I wrote in The Open Road, cars were made legal to run in England’s open roads in November 1896, with the Light Locomotives on Highways Act. The Act set the speed limit to 12 Mph, and superseded a previous Locomotive Act from 1865, which set a speed limit of 4 Mph and demanded that the car was preceded by a man on foot waving a red flag, which kind of defeats the purpose.

Roads and highways were often unpaved and unprepared for a superior speed, as people very rarely went racing in stagecoaches, although that was not unheard of.

Only nine models of cars were manufactured in the UK at the time when Grahame wrote The Wind in the Willows.

The Albion 24/30 was the fourth model of car produced by Albion Motors, following the Albion 8, the Albion 12 and the Albion 16. It was a 4175 cc 4-cylinder and it would be the penultimate before the Scottish firm ceased its production of passenger cars in 1915.

The first Argyll car was produced in 1899 at The Hozier Engineering Company, a factory founded by one Alex Govan. The car was fundamentally a Renault rip-off, though significant updates were made between 1902 and 1903. The Company changed its name to Argyll Motors Ltd. and eventually grew enough to have its own private railway line for supplying parts, opened in 1906 by John Douglas, 2nd Baron Montagu of Beaulieu, a big supporter of motorization in Great Britain. The Company went into decline when its founder died in 1907, and by 1908 it was being liquidated for bankruptcy. It would be revived in 1910, and called Argylls Ltd., but The Wind in the Willows’ outline would have been mostly completed, by then.

If Toad’s car was an Argyll, it could have been a model 14 16, one of the last produced before the Company’s downfall.

The Austin Motor Company Limited was founded in 1905 by Herbert Austin, as a spin-off of his successful Wolseley Sheep Shearing Machine Company based in London, after having built three of the first British cars in his spare time around 1895. The Company produced its first 31 cars in 1906. The following year, the number would go up to 180 and we might like to think that Toad was amongst one of them. If so, the car might have been the 25/30 hp open tourer.

The Daimler Motor Company Limited, which adjusted its name in 1910, is known as Britain’s oldest car manufacturer and is associated with the Royal Crown since it received patronage from Edward VII in 1908. Not that it would have made Badger change his mind on the subject, as we know. The 48hp from 1908 would certainly be a good candidate for Toad. And take a look at that red!

The motor division of the already existing Humber Limited, which specialized in cycles, began in 1896 and struggled to take off the ground until the company was sold to Raleigh in 1932. The car production started with a prototype and nine exemplars, followed in November 1896 by an exhibition of one of those prototypes at the Stanley Cycle Show in London. Proof of this exhibition gives Humber the right to claim they produced the first motorcar on British soil.

At the time of The Wind in the Willows‘ writing, the Humber 10/12 and the Humber 30/40 were both in production.

The D. Napier & Son Limited company built luxurious cars after 1895, when Montague Stanley Napier inherited a failing business from his father. A passionate car racer himself and a talented engineer, he sold his first six cars in 1900 sharp. They were an 8 hp and a 16 hp. On behalf of the novelist Mary Eliza Kennard, they entered the Thousand Miles Trial of the Automobile Club in 1904, being the first British car to do so, and they won their class with Kennard herself on board. The Company will later continue its tradition of women riding its cars: look Dorothy Levitt up if you don’t believe me.

I like to think this particular attention to racing might have drawn Toad’s attention.

If so, the purchased car might have been a Napier 60.

Rover, as in Range Rover and Land Rover, is possibly the most influential Company amongst this bunch. Like Humber, it had been a bicycle manufacturing company since 1885, and moved to motorcars in 1904 although its first one was en electrical car from 1888, never produced. The first cars were designed by Edmund Lewis, who had previously worked at the Damier Company, and around 1907 we have three models being produced: the 8, the 6, the 10/12, the 16 and the 20.

If Toad was partial to any of these, it had to be the latter, a replica of the car which won the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy Race in 1906. It’s an open tourer, and it comes in red.

Vauxhall Motors Limited was founded in 1857 by a marine engineer, and initially produced boat engines. They tried their hands at motorcars in 1903, with 70 exemplars of a a 5hp single-cylinder model, and it had a tiller – like a boat – instead of a steering wheel. Maybe Rat would have approved of this particular motor, but a more sensible approach was taken in 1904.

Around 1907, its cars were being designed by a young talent named Laurence Pomeroy, 22 at the time, who designed a wonderful car during his boss’ vacation and swiftly took his place. Subversive and revolutionary, the Y-Type Y1 would perfectly fit Toad’s tastes. I unfortunately don’t have a picture for it.

Last but not least, Wolseley Motors produced some wonderful cars between their establishment in 1901 and 1905, but the two-cylinder Wolseley-Siddeley is the only one recent enough to be enthralling for a character such as Toad.

When Jan Needle wrote his sequel The Wild Wood in 1981, he wrote that Toad’s favourite car was an Armstrong Hardcastle Special Eight. Though Armstrong Siddeley was a British engineer group active in car design and spun off from Wolseley, I don’t think Armstrong Hardcastle has ever been a thing.

Eccentric Countrymen and their Motorcars

It’s impossible to talk about Toad, and Grahame, to mention Tolkien and not draw attention to one of the strongest parallels between the two authors: Tolkien’s Mr Bliss. David Sander wrote an essay about it called Mr. Bliss and Mr. Toad: Hazardous Driving in J.R.R. Tolkien’s “Mr. Bliss” & Kenneth Grahame’s “The Wind in the Willows”, published on Mythlore in September 1997. Of course, you can’t read it unless you’re willing to sacrifice your firstborn to Jstor.

Mr Bliss was written and illustrated by Tolkien around 1935 and never published, though he had submitted it to his publisher after The Hobbit, when people were harassing him for more tales.

According to Humphrey Carpenter in his biography:

The purchase of a car in 1932 and Tolkien’s subsequent mishaps while driving it led him to write another children’s story, ‘Mr Bliss’. This is the tale of a tall thin man who lives in a tall thin house, and who purchases a bright yellow automobile for five shillings, with remarkable consequences (and a number of collisions).

— H. Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography.

Though Beatrix Potter is more often quoted as the inspiration for this book, because of it being hand-illustrated and neatly bound, we can’t ignore the strong Toad vibes coming from the main character’s driving style.

After trading his silver bicycle for a yellow car, Mr Bliss’ misadventures include several accidents, but he’s immediately more sympathetic than Toad: Mr Bliss is just eccentric, not a bully, and every time he damages one of his neighbours he tries to make up for it. When he hits poor Mr Day and his barrow-load of cabbages, he haults him (and the cabbages) on his car, and does the same with Mrs Knight and her donkey-cart of bananas.

Mr Bliss’ adventures also involve crossing through a dark wood, delightfully illustrated in such a way that’s impossible not to think of Mirkwood (I wrote about its connections with The Wind in the Willows’ Dark Woods over here), the encounter with the three feral (teddy) bears Archie, Teddy and Bruno.

So Mr Bliss had to stop, because he could not get by without running over them.

“I like bananas,” said Teddy.

“And I like cabbages,” said Archie.

“And I want a donkey!”, said Bruno.

“And I want a motor-car,” they all said together.

“But you can’t have this motor-car, it’s mine”, said Mr Bliss.

“And you can’t have these cabbages — they’re mine”, said Mr Day.

“And you can’t have these bananas or this donkey — they’re mine”, said Mrs Knight.

“Then we shall eat you all up — one each!”, said the bears.

Of course, the bears want a lift too, so now Mr Bliss’ car has Mrs Knight, Mr Day and three bears, with the donkey tied behind.

Thus encumbered, the car’s brakes don’t function properly, and the group sends it crashing against the Dorkinses’ garden wall.

Eventually, Mr Bliss is forced to have his wrecked car towed by the donkey and his neighbours’ ponies.

Eventually, Mr Bliss has his troubles with authorities too, as the whole neighbourhood blames him for their misfortunes though, to be honest, a fair share of the blame is to be laid on the bears. Sargeant Boffin, a name we’ll find again in the Shire, leads an expedition of furious townspeople who want compensation from the eccentric gentleman and storm his gate.

Mr Bliss is a man of honour, though, and the story ends with him breaking his money-box, and settling his debts with everybody, with an additional touch of community for a happy ending.

…Mr Bliss is quite happy. […] He drives a little donkey cart now, not a motor, and Sergeant Boffin salutes him every time he appears in the village.

I think we’ll have a hard time comparing his attitude to the one of Toad.

1 Comment

Pingback:Washerwomen and Cross-Dressing Heroes: Toad’s Great Escape – Shelidon

Posted at 15:40h, 20 May[…] we’ve reached Chapter 8 in the re-reading of The Wind in the Willows (I already mentioned it here and here), and Chapter 8 is where we see Toad’s misadventures reaching a peak of misery: the […]