The second tale in Kenneth Grahame’s Wind in the Willows takes up from where we left our two favourite characters: Rat, in his river-house, and Mole who ended up living with him.

Specifically, the story opens with Rat doing one of the things he does best: sitting by the river and singing a song. As Annie Gauger points out in her Annotated Wind in the Willows, if the story is a miniature epic, Rat is a romantic bard, whose main occupation is telling stories, improvising songs and poetry, writing. We had already seen him in chapter I, “murmuring poetry-things over to himself”.

The specific song he is writing has to do with his meeting with some ducks, and the event is probably inspired to Grahame by Oscar Wilde’s short story “The Devoted Friend” included in The Happy Prince (1888), where we precisely see a Water Rat meeting some ducks. The very way Rat is described in putting his head out of his hole in a similar way we have seen Rat doing in Chapter I:

One morning the old Water-rat put his head out of his hole. He had bright beady eyes and stiff grey whiskers, and his tail was like a long bit of black india-rubber.

That’s when Oscar Wilde’s Rat meets some yellow ducklings, swimming about with their pure white mother who’s trying to teach them how to stand on their heads under water because that’s the proper thing to know if you want to be in the best society. Wilde’s little ducklings however don’t pay attention to her: «They were so young that they did not know what an advantage is to be in society at all».

The story has been adapted in comic book form by the cartoonist Philip Craig Russell, the first mainstream comic book creator to come out as openly homosexual, in the Fairy Tales of Oscar Wilde from NBM Publishing.

All social criticism is lost, of course, in the poem written by our upclass Rat. The song is often referred to as “Ducks’ Ditty” and is one of the most popular pieces of poetry Graham ever did: it is often printed on its own and it was included in anthologies so much that his widow received rather handsome sums of money from its royalties.

“All along the backwater, / Through the rushes tall, / Ducks are a-dabbling, / Up tails all!

Ducks’ tails, drakes’ tails, / Yellow feet a-quiver, / Yellow bills all out of sight / Busy in the river!

Slushy green undergrowth / Where the roach swim— / Here we keep our larder, / Cool and full and dim.

Everyone for what he likes! / We like to be / Heads down, tails up, / Dabbling free!

High in the blue above / Swifts whirl and call— / We are down a-dabbling / Up tails all!”

Grahame went to considerable lengths in order to eliminate any hint of sexuality from his book (he even took out a rather innocent Mrs Mole, that was present in earlier stories sent to his son by letter), but apparently he missed – or willingly choose to ignore – this one: Uptails all is slang for having sex, since 1640, and it’s the title of a very explicit poem written by Robert Herrick in 1648. Grahame knew Herrick very well, he was one of his favorites, and he included some of his poems in The Cambridge Book of Poetry for Children he curated in 1914. It s rather fun, however, imagining a quiet Rat composing a poem about some ducks he had seen frolicking on the river, and the fact he’s composing it after he had been “swimming” with them makes it even more amusing. As we said, Rat is a bard, and bard are known to do these kind of things. This also gives us a new kind of interpretation on the fact that Mole is rather perplexed at hearing the poem and, according to Rat himself, so were the ducks.

“They say ‘Why can’t fellows be allowed to do what they like when they like and as they like, instead of other fellows sitting on banks and watching them all the time and makig remarks and poetry and things about them?'”

This makes more sense.

Mole, however, is not the poetry tipe yet, at this point in the story, and he’s interrupting Rat’s questionable activities because he has a request: he would like for Rat to bring him and introduce him to this Mr. Toad everyone’s talking about. Since Toad is a good-natured fellow and every hour is the right hour to pay him a visit (he’s rich and he has absolutely nothing to do).

Toad Hall is described as a mix of lots of houses Grahame admired: «a handsome, dignified old house of mellowed red brick», with a boathouse for parking, stables, a very old banqueting hall. It’s one of the best houses in the river, though Rat says that they rarely admit it in front of Toad and, as we’ll see, Toad does enough boasting by himself.

Humphrey Carpenter, that lots of you probably know for being Tolkien’s biographer, wrote about Grahame’s Toad in his Secret Gardens: A Study of the Golden Age of Children’s Literature, and rightly points out:

Toad represents the opposite of [Badger’s] stability. His exact social position is never made clear; he is described as behaving like ‘a blend of the Squire and the College Don’, and it is clear that Toad Hall has been in his family for more than one generation; yet the narrative constantly gives the impression that he is a parvenu whose family has bought its way into the squirearchy rather than inherited its position. Badger censures Toad for ‘squandering the money your father left you’, and there seems to be a hint that Mr Toad senior made that money in the cotton trade or something less decorous.

And he adds, in a footnote:

As to education, Badger was undoubtedly at Winchester and New College. Rat presumably went to a minor public school which had a headmaster who admired Arnold and Maurice, and Mole was perhaps a pupil at a provincial grammar school. One could imagine Toad enjoying a brief period at Eton or Harrow before being expelled.

As soon as they arrive, Rat immediately deduces that the deserted boathouse and the abandoned boats only signify that the newly-found passion for racing in boats has already passed, as he had foreseen in the previous chapter, and the two friends find Toad sitting on a wicker-chair in his well-tended garden, looking at a map. We see no servants, nor we will ever see any, but a hint in what he says about sending for Rat clearly suggests there is that kind of invisible servant we are used to appreciate in Julian Fellowes‘ mansions (and if you’re familiar with Downton Abbey, I suggest you check out his previous mystery movie Godsford Park, in which lots of themes are anticipated). His new passion is, in fact, a gipsy caravan.

He led the way to the stable-yard accordingly, the Rat following with a most mistrustful expression; and there, drawn out of the coach-house into the open, they saw a gipsy caravan, shining with newness, painted in a canary-yellow picked out with green, and red wheels.

Toad wants to pick up a nomad life and pitches the idea to both Rat and Mole with his characteristic passion:

“There’s real life for you, embodied in that little cart. The open road, the dusty highway, the heath, the common, the hedgerows, the rolling downs! Camps, villages, towns, cities! Here to-day, up and off to somewhere else to-morrow! Travel, change, interest, excitement! The whole world before you, and a horizon that’s always changing! And mind! this is the very finest cart of its sort that was ever built, without any exception”

Toad is also very proud of the interiors he had planned for himself, another peculiar thing that brings him closer to an eccentric wealthy countryside nobleman: inside, with the eyes of Mole as it often happens, we little sleeping bunks, a little table that folds against the wall, a cooking-stove, lockers, bookshelves, lots of pots and pans, and a birdcag with a bird in it, an object Grahame always use – following the tradition of Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield – to signify imprisonment. In this case, Toad’s claustrophobic cart is proving to be too much for Rat’s disposition and taste.

Though Grahame’s son Alastair had received a small gypsy cart as a gift for his fifth birthday, it’s highly likely that the inspiration for this new fancy of Toad’s is to be traced back to another fictional character of Grahame, Fothergill, in the story “A Bohemian in Exile”, who takes up the road pushing samples, brewing beer and telling fortunes, though his cart is not described as a «fashionable gipsy cart» and is more similar to «a house-boat on wheels». In turn, this character was based on a colleague in the Bank of England who had done precisely what Toad wants to do: giving up his life to take up nomadic adventuring in a gypsy cart.

Fothergill bought a medium sized “developed” [cart] and also a donkey to fit; he had it painted white, picked out with green—the barrow, not the donkey—and when is arrangements were complete, stabled the whole for the night in Bloomsbury. The following morning, before the early red had faded from the sky, the exodus took place.

Again, shoud, you wish to set up a Toad-themed menu for a special afternoon or in case you want to take up the open road in style, Grahame has you covered and here’s your menu: it’s simply biscuits, potter lobster, sardines, bacon, jam soda water and tobacco for when you’ll want to play cards and dominoes.

Toad has arranged for his friends to go with him, as his temperament is quite the opposite of Badger’s and he doesn’t seem to stand being alone. Rat of course doesn’t want to leave his boat house to follow Toad along his whimsical caprices, but Toad is enthralled by the idea and Rat «hates disappointing people», so the three have luncheon (and unfortunately we don’t have the menu for this) and they leave in Toad’s cart.

They spend the afternoon on the road and the evening together, dining on the grass, and by night time Mole has to comfort Rat, who misses his riverside. By morning, they have breakfast with milk and eggs Toad buys from the nearby village, and we see more of the fact that Toad is expecting his friends to do all the work. The patient Rat encourages Mole to wait for this new passion to fade, but misfortune strikes on the high-road, basically a 1709 word for what we would now call a highway, where Toad sees his first car.

Glancing back, they saw a small cloud of dust, with a dark center of energy, advancing on them at incredible speed, while from out the dust a faint “Poop-poop!” wailed like an uneasy animal in pain.

Cars were made legal to run in England’s open roads in November 1896, with the Light Locomotives on Highways Act which also set the speed limit to 12 Mph, as of course they were accepted with mixed feelings. The Act was superseding the previous Locomotive Act from 1865, which set a speed limit of 4 Mph and demanded that the car was preceded by a man on foot, waving a red flag, which kind of defats the purpose of using a car. Roads and highways were often unpaved and unprepared for a superior speed, as people very rarely went racing in stagecoaches, although that too is described as a debauched and reckless behavior in novels such as Jane Austen’s. Another tricky topic was the fact that animals were not accustomed to seeing cars and motors scared them, which is precisely what we see happening in this scene from The Wind in The Willows.

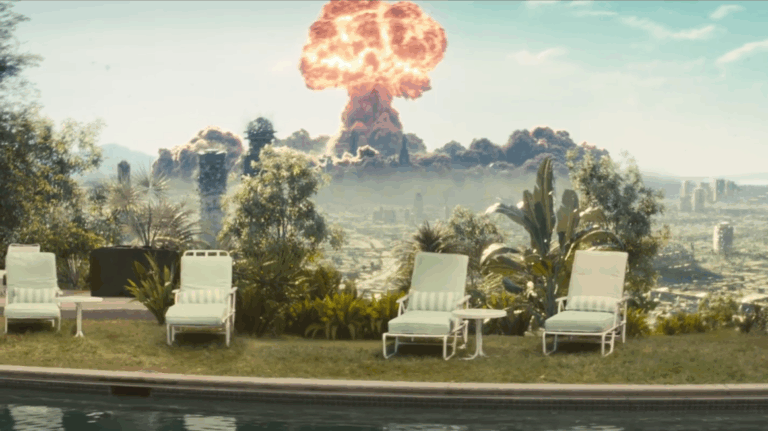

“Hardly regarding it, they turned to resume their conversation, when in an instant (as it seemed) the peaceful scene was changed, and with a blast of wind and a whirl of sound that made them jump for the nearest ditch. It was on them! The “Poop-poop” rang with a brazen shout in their ears, they had a moment’s glimpse of an interior of glittering plate-glass and rich morocco, and the magnificent motor-car, immense, breath-snatching, passionate, with its pilot tense and hugging his wheel, possessed all earth “and air for the fraction of a second, flung an enveloping cloud of dust that blinded and enwrapped them utterly, and then dwindled to a speck in the far distance, changed back into a droning bee once more.”

The way the car strides along and is described with a mixture of horror and enchantment. By the time Grahame writes, cars were luxury items and many people had taken a shine to them, including authors like Rudyard Kipling, but the idea of an eccentric gentleman taking up driving and wrecking havoc in the quiet contryside will not be new to Tolkien’s fans among you, as it’s one of the main plot topics of a minor illustrated tale, Mr Bliss, published posthumously in 1982.

In this tale, a hotizontal leaflet fully hand-written and illustrated by Tolkien himself, the eccentric Mr Bliss trades his silver bicycle for a yellow car with red wheels and wreaks havoc among his neighbors, giving lifts to bears and donkeys.

This, as we will see, will not be too far from how Toad himself will fare with a motorcar, but for now we see him sitting in the middle of the road, thunderstruck, while his friends try to straighten up the cart and cheer up the horse (a horse so gloomy that it will probably be among the inspirations for A.A. Milne’s melancholic donkey Eeyore). Toad friends are unable to break the spell, as he keeps repeating how wonderful would be to have a cart and is now charmed by this new whim of passion.

O bliss! O poop-poop! O my! O my!

Rat advises Mole that there’s nothing to be done: Toad will be like that for days, completely useless. Toad catches up with the only to keep repeating how marvelous the car was, and to make clear that he has no intention of mending the wagon. In describing the car, where Mole uses a generic and terrified Thing as if it was the Frankenstein’s monster, Toad picks three attributes of Zeus himself: the swan, the sunbeam and the thunderbolt. He is definitely and officially gone. The three friends have to leave he horse to an Inn and take a train back to Toad Hall. There, we cross path with two of the invisible nameless servants, the porter and the housekeeper, and is sent to bed.

The next morning, the rivebank is all a chatter.

“There’s nothing else being talked about, all along the river bank. Toad went up to Town by an early train this morning. And he has ordered a large and very expensive motor-car”.

Toad’s portrayals and adaptations

Since this is the first story properly featuring Toad, and since a great part of the book is occupied by his misfortunes following the purchase of the motor-car, this second chapter is often the first scene we see in adaptations focusing on Toad, such as A.A. Milne’s play and Disney’s cartoon. See here for all the adaptations featuring him and the different ways he has been portrayed.

The differences in Disney’s version are many: the story is set in London, and characters are distinctively humanized. Toad becomes J. Thaddeus Toad, Esquire, and Badger is here seen as his friend MacBadger, who volunteers as his bookkeeper in order to try and save him from bankrupcy. It is in this scene that MacBadger asks Ratty and Moley to try and stop Toad in his new hobby, to run up and down the countryside in a horse and canary-yellow gypsy cart, damaging other people’s property. It is in this attempt that Toad has his unfortunate first meeting with a car, although we’ll see that Disney lifts a great deal of responsibility from our amphibious friend.

Disney started having meetings about an adaptation of The Wind in the Wiillows while he was working on Fantasia, and the idea came from the story research department led by John Clarke Rose, a former artist who had studied under Pruett Carter. Among the many titles that were selected for a possible full-length movie, alongside The Wind in the Willows, we see lots of stuff which was eventually produced- like Alice in Wonderland, Cinderella, Peter Pan – and stuff that was either used in a shorter version or significantly changed, such as Jack and the Beanstalk and King Arthur. There’s also stories like Don Quixote, upon which lots of people worked for a very long time, but never saw the light. The purpose of Rose’s department was to mitigate the risk in embarking in the production of a full-length picture before the story’s potential had been carefully analyzed, something that was happening a lot for shorter features and was likely to bankrupt the studio if done on a long movie.

The first artists to do storyboards for the project were James Bodrero and Campbell Grant. Storyboarding was being invented, at the time, and Bodrero would lately recall how they impressed the studio by flicking through stills of a storyboard in front of the meeting.

Bodrero was particularly fond of the project and he takes credit for convincing Walt Disney to do it, though the Man tought it was «awfully corny» (see his interview with Milton Grey in 1977, featured in Volume 8 of Walt Disney’s People by Dider Ghez). Disney had already received a copy of the book in 1934 from an English correspondent, one Lady Carlisle, and the studio’s library also had two copies of Milne’s adaptation, so at least the story of Toad was well known.

The infamous strike of 1941 put the project on hold and Bodrero, a prominent figure among the non-strikers, had to wait two years for it to start again, and to be reassigned alongside his assistant Campbell Grant and other artists such as Tom Oreb, whom we know for a fact was creating story sketches around that time, Perce Pearce and Paul Girard Smith.

Grant came back to work on the project also in 1946 when he recorded the voice for the now extremely Scottish character of Angus MacBadger. Campbell Grant did character sheets such as the one below, for Ratty, who is portrayed with an acute Sherlock Holmes vibe.

I am not very fond of the way animals were characterized in this adaptation, but I am rather fond of the study the same Campbell Grant did for another important character in the story: Toad’s car. Both sketches and the information I gave you so far feature in one of the books I’ve been quoting a lot for my Fantasia series: They Drew as They Pleased by Dider Ghez.

Another very important artist involved in the development of the movie was Mel Shaw, whom I believe I already mentioned when talking about Disney’s Fantasia and aspecially the Pastoral Symphony piece. Shaw attended story meetings since September 1940 and he was very fond of the project. In his Animator on Horseback, he wrote:

Wind in the Willows was a wonderfully whimsical subject, and I especially enjoyed the eccentric “Mr. Toad” portion of the book. I worked very closely with Larry Morey, who was a fine story artist as well as a lyricist for many Disney soundtracks. As we began to develop these creatures from the English countryside, we found that caricaturing our subjects with a British demeanor was interesting animation. The flamboyant “Mr. Toad” had his close comrades, “Ratty,” “Moley,” and the conservative “McBadger,” all in a dither during most of the story. I worked on the storyline for about eight months before it was ready to be turned over to the animators.

The movie will eventually come out in 1949 in the package movie The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr Toad, and it’s the last package movie Disney will produce until The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh in March 1977. The other package movies from the 1940s are Saludos Amigos, The Three Caballeros, Make Mine Music, Fun and Fancy Free, and Melody Time.

2 Comments

Pingback:The Wind in The Willows (7): The Piper at the Gates of Dawn – Shelidon

Posted at 00:07h, 16 January[…] one of the artists to work on the early concept of the project and I do believe I talked about him here. That’s all the Toad we’re going to […]

Pingback:Mr Toad’s Motorcar – Shelidon

Posted at 10:04h, 01 May[…] now reached Chapter VI and, as I already mentioned when talking about The Open Road, I’m not very fond of the character of Toad, and I’ve got a lot of reasons, some […]