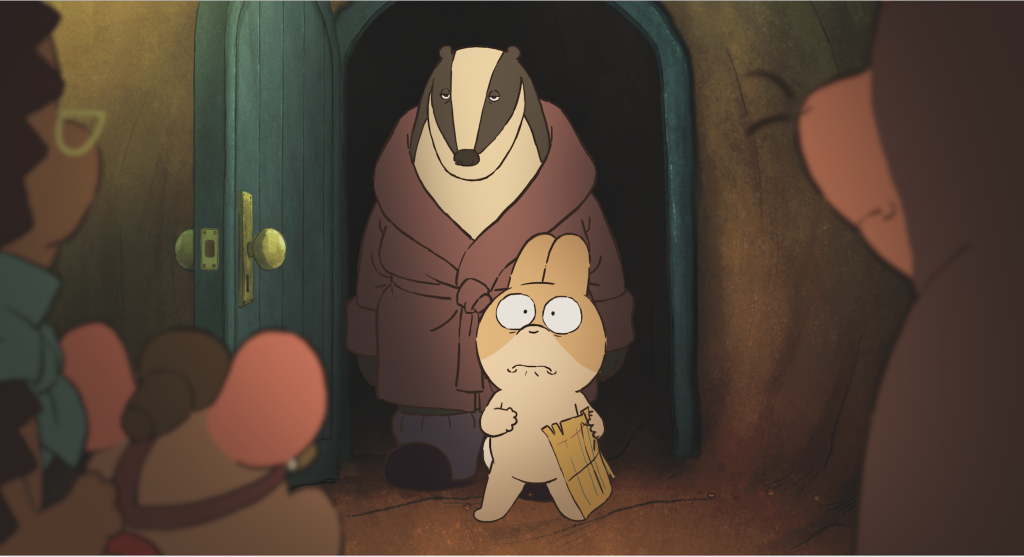

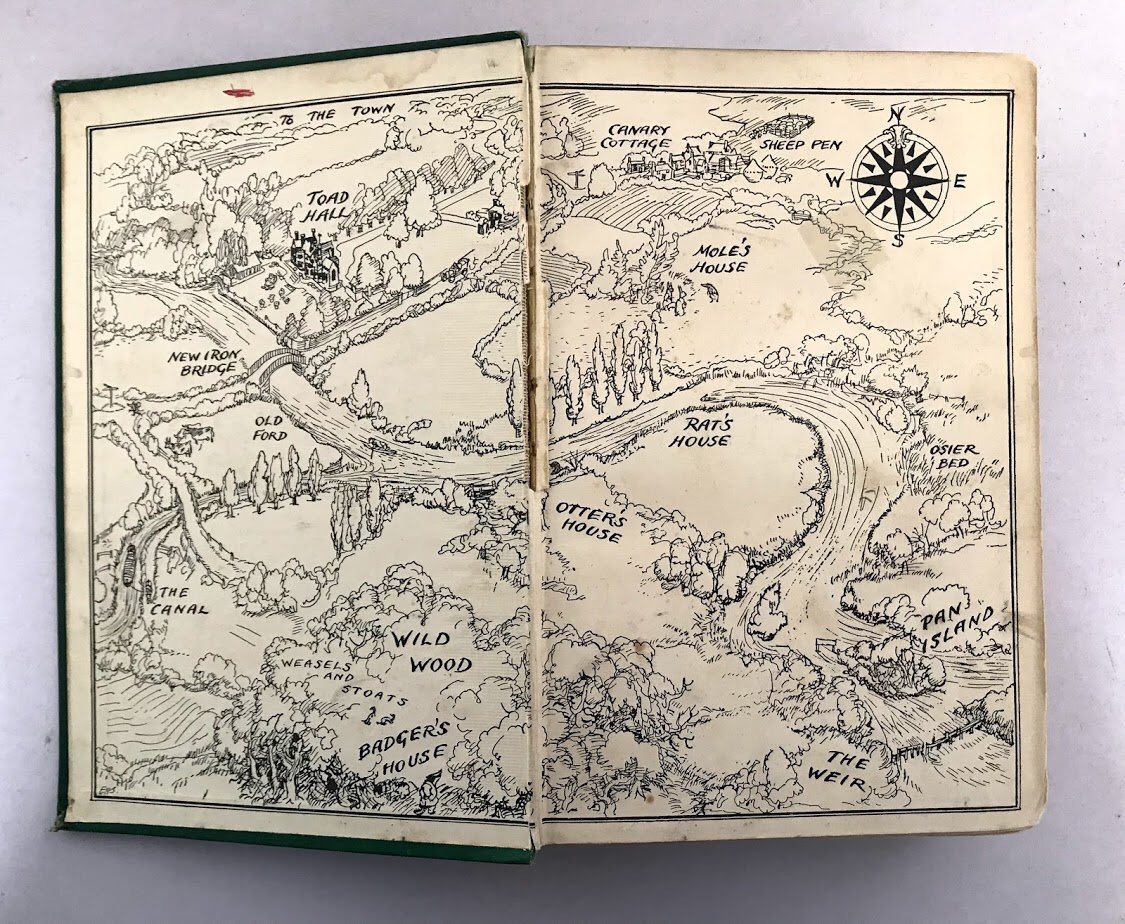

This is my absolute favourite piece and it often gets skipped in antologies and renditions because there’s no Toad in it (which is fine with me, as I’m not overly fond of the character): it’s where we venture with Mole into the perilous Wild Woods to meet my favorite character, Badger (though we actually do not meet him in this chapter, but rather in the next).

The story of Chapter III starts with a change of pace in seasons: summer is over and the weather is getting in the way of Rat’s and Mole’s amusement. Mole is still living with Rat, at this point in the story, with no hint of wanting to go back to his own house, but «cold and frost and miry ways kept them much indoors, and the swollen river raced past outside their windows with a speed that mocked at boating of any sort or kind».

Mole had often inquiried about inviting the elusive Badger to have lunch with them, or going up to visit him, but Rat has been putting off his excitement: Badger doesn’t like social calls and, regardless of that, Rat never ventures to visit Badger because he lives in the Wild Wood and that’s a dangerous spot.

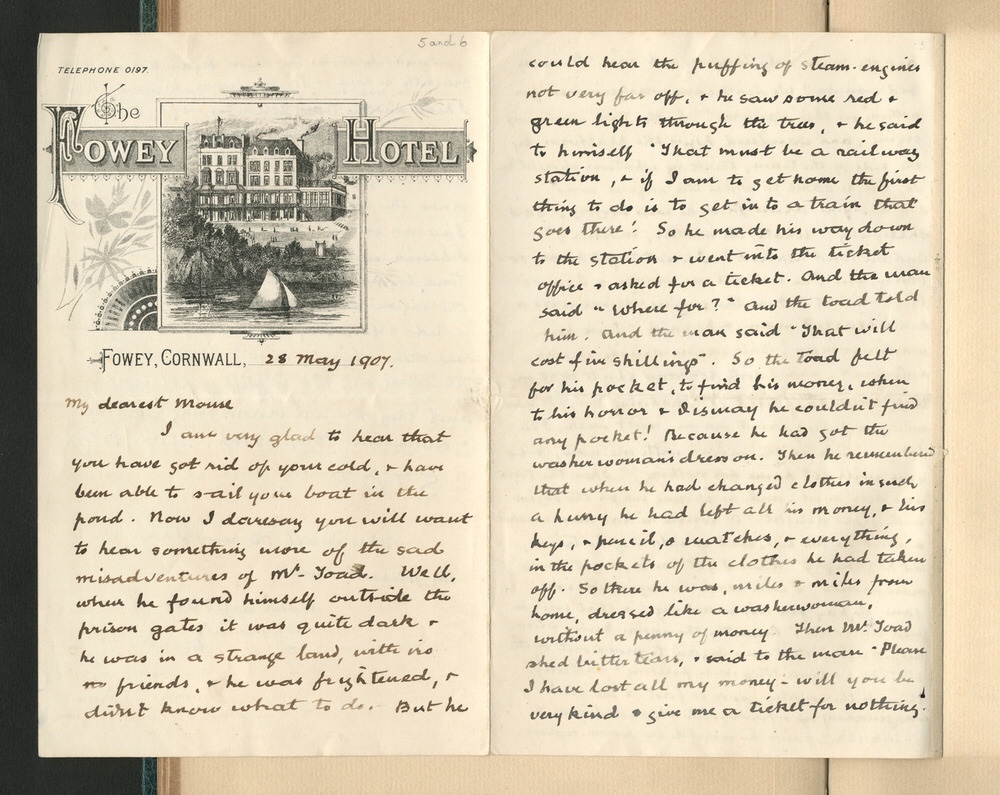

Lots of the stories originally came from Grahame narrating to his child Alastair, but lots of elements suggest that it was more of a joint effort: one Arthur Quiller-Couch had the chance of standing outside the night nursery of an Inveraray hotel in 1905, where the family was staying for a vacation, and listening to Grahame tellin a story to Alaistair, and to the visitor it sounded more like they were building the story together, through Grahame’s narration and through the child’s questions and requests.

The first draft of this particular story, therefore, is not handwritten by Grahame: we can find it in a letter sent by Alastair’s beloved governess, Naomi Stott, in a letter probably dated 1909.

The mole & the water rat go to Badger Hall in the wild wood. On their way it comes on to storm & rain, & they get lost.

The mole falls over something hard that hurts him & finds that it is a door s

Nancy Stott in a letter to Kenneth Grahametepscraper. Then they find a door, & Mr. water rat’s house keeper [she probably meant ‘Badger’s] says “What do you mean? You must go round to the front door.” She grumbles, but at last lets them in at the back door, & Mr. Badger gives them clothes & supper, & they all have a good time, & the next day they go off.

She then adds, referring to Alastair with the family nickname: «If you could tell me any leading questions I might casually be able to extract some more. Mouse as just given me that small amount I have written down».

It is possible that Grahame wouldn’t have included scenes so far away from the riverbank, if not prompted by his chiWe have heard Rat talking about the Woods before, in Chapter I, but at this point in the tale the concept needs reinforcement. What we’re going to read is without any doubt a chapter in which the Woods are playin the part of a character, just like the River had in Chapter I and, to a certain extent, largely surpassing what the road had been doing in Chapter II, though that might have been the author’s intentions.

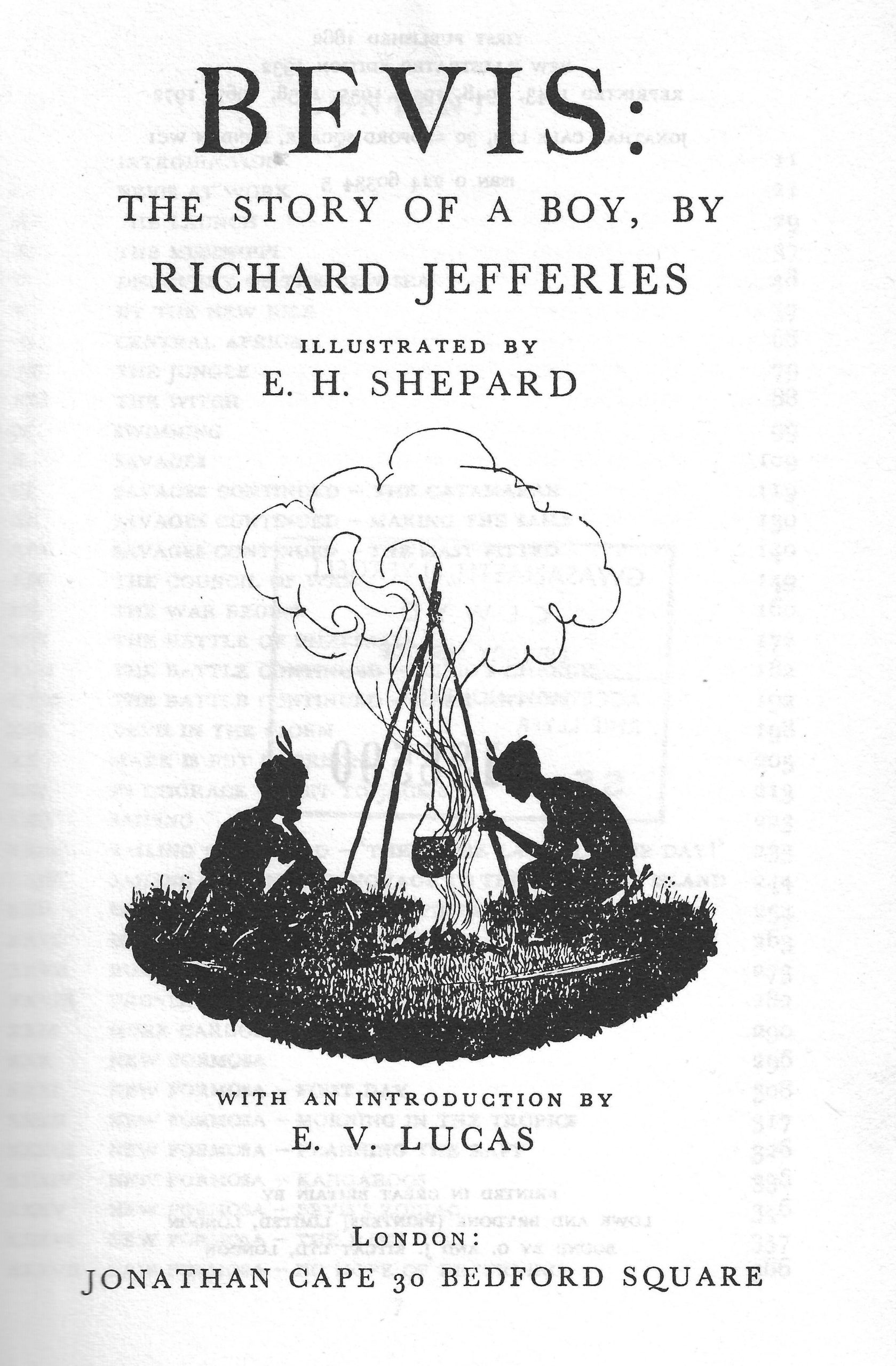

Humphrey Carpenter in his Secret Gardens suggests that the inspiration for landscape characterization, aside from the obvious observation of his beloved countryside surroundings, might have been Richard Jefferies, an English nature writer who worked a lot in depicting English rural life in essays, books of natural history, and novels. Carpenter suggests that the most influential work in this context might have been his Wood Magic: A Fable (1881). Here we meet Bevis, a small child who lives in a farm near the lake of Longpond and, during his exploration of the garden and surrounding fields, Jeffries «supplies the notion of tribal and social upheavals among the animals, and even has passages where words are whispered by the reeds, the river, and the wind». This novel too and its sequel were illustrated by E.H. Shepard, who seems to be pretty much everywhere there’s rural England. Carpenter decides to focus, however, on the social and sexual metaphors the Wild Wood holds, in his opinion, and we shall have nothing of that here.

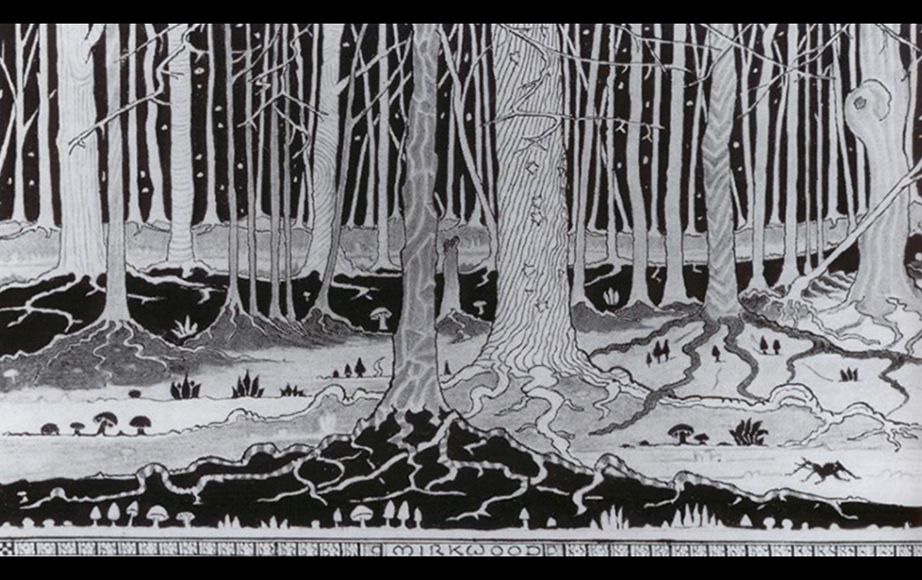

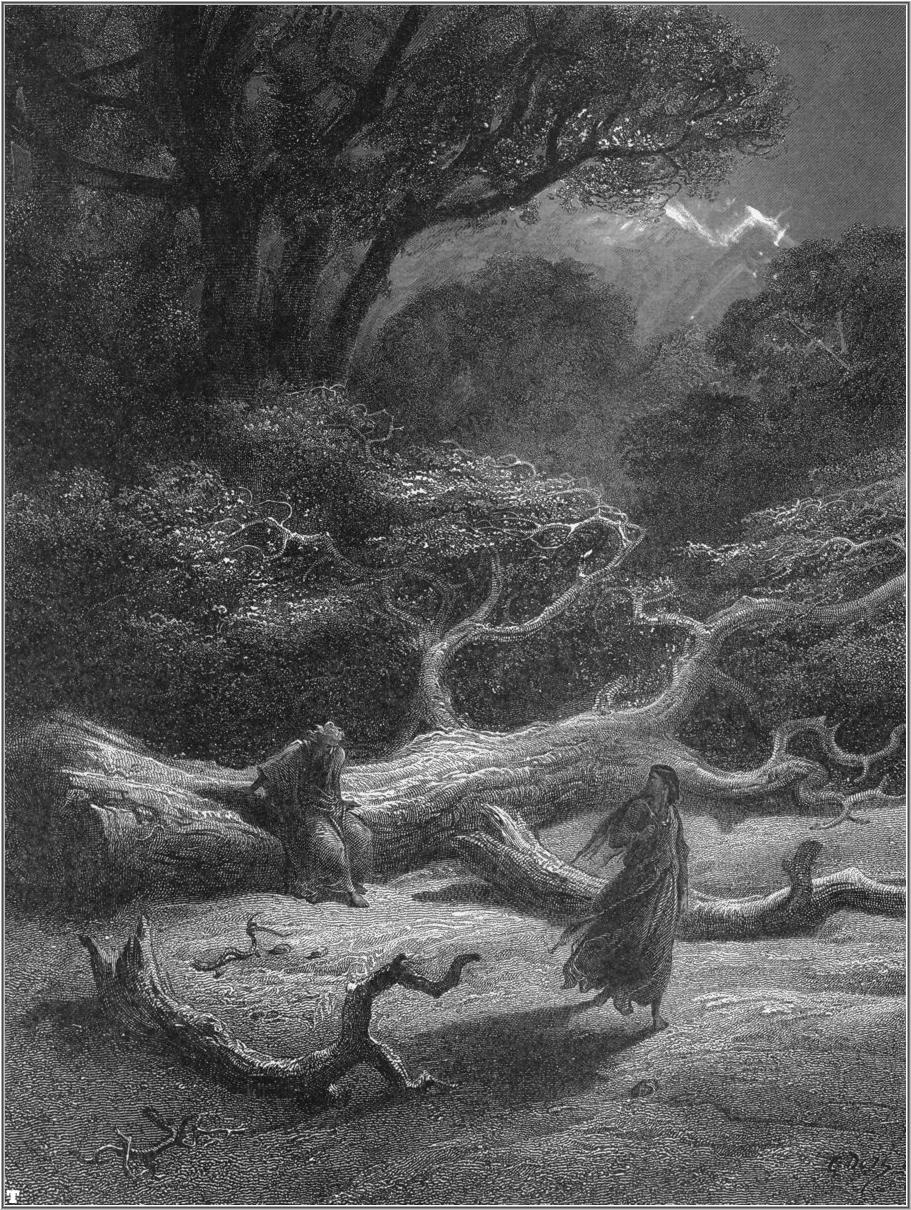

Woods are a liminal place, in fairy-tales, like shores and mushroom circles. They are borders, in-betweens, places where anything can happen. This particular Woods are especially menacing, like Tolkien’s Mirkwood or, better still, the Woods in E.A. Wyke-Smith’s Marvellous Land of Snergs. If Tolkien’s Mirkwood is described, in The Hobbit, with strikingly architectural metaphors and his trees resemble pillars in some abandoned hall, Wyke-Smith presents us with horrible twisted grey logs, ready to be mistaken for terrifying faces.

Tolkien’s primary influence, starting from the name, is however the Old Norse forest of Myrkviðr, as he himself admits in a letter: «Mirkwood is not an invention of mine, but a very ancient name, weighted with legendary associations. It was probably the Primitive Germanic name for the great mountainous forest regions that anciently formed a barrier to the south of the lands of Germanic expansion. In some traditions it became used especially of the boundary between Goths and Huns. I speak now from memory: its ancientness seems indicated by its appearance in very early German (11th c.?) as mirkiwidu although the *merkw- stem ‘dark’ is not otherwise found in German at all (only in O[ld] E[nglish], O[ld] S[axon], and O[ld] N[orse]), and the stem *widu- > witu was in German (I think) limited to the sense of ‘timber,’ not very common, and did not survive into mod[ern] G[erman]. In O[ld] E[nglish] mirce only survives in poetry, and in the sense ‘dark’, or rather ‘gloomy’, only in Beowulf [line] 1405 ofer myrcan mor: elsewhere only with the sense ‘murky’ > wicked, hellish. It was never, I think, a mere ‘colour’ word: ‘black’, and was from the beginning weighted with the sense of ‘gloom’.»

Other British gentlemen to dabble in such woods before Tolkien (and Grahame) were Sir Walter Scott in his historical novel Waverley (1814) and William Morris in The House of the Wolfings, often considered to be the first modern fantasy novel, from 1889.

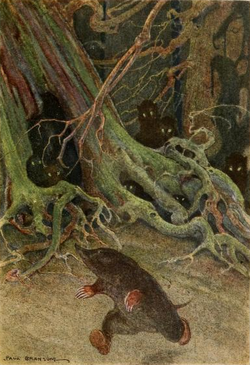

Mole’s entrance in such a realm is slow and gentle enough, though the Woods lay menacing in front of our hero. The danger is part of the woods’ charm, at first.

Twigs cracked under his feet, logs tripped him, funguses on stumps resembled charicatures, and startled him for the moment by their likeness to something familiar and far away; but that was all fun, and exciting. It led him on, and he penetrated to where the light was less, and trees crouched nearer and nearer, and holes made ugly mouths at him on either side.

Even if I don’t like his constant stress on sexuality, there’s one additional interesting consideration we find about the Wild Wood in Carpenter’s book: it’s a place where imagination can run rampant and give way to our worst nightmares, if we let it.

Charles Williams, friend of C.S. Lewis, used the wood Broceliande to carry just this meaning in his Arthurian cycle of poems, Taliessin through Logres. Williams described this wood as ‘a place of making’, from which either good or evil imaginings may come, and so it is with Grahame’s Wild Wood.

H. Carpenter, Secret Gardens: a study on the golden age of Children’s literature

Soon, our Mole starts seeing things. The apparitions that initially startled him as a resemblance take a life of their own, in a series of hallucinations that grow more and more menacing. Grahame uses the rethorical figure of repetition, with sentences all composed with fhe same structure: «Then the … began». We start with faces, then whistling, then pattering, going from the more defined to the less, and thus increasing terror. It has been said that Mole’s descent in the Wild Woods has striking similarities to what might have been the experience of a middle/upper-class fellow who strayed into London’s suburbs and criminal havens as described by Charles Dickens and Arthur Conan Doyle (see Sherlock Holme’s underground London). Though I do not want to deny that the tale’s character are socially characterized in a very precise way – and this will later turn Wind in The Willows into a social clash, when the weasels take over Toad Hall – these kind of scenes usually include an encounter with a lowlife trying to pose as a helper. If you don’t wan to dig your noses in a book, think of the similar scene in Disney’s adaptation of Mary Poppins, when the children run away from the Bank and end up in the suburbs, a scene later echoed in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets when our hero mistakenly wanders into Knocturne Alley. There’s always en encounter.

Then suddendly, as if it had been so all the time, every hole, far and near, and there were hundreds of them, seemed to possess its face, coming and going rapidly, all fixing on him glances of malice and hatred: all hard-eyed and evil and sharp.

More than the descent into the overcrowded London suburbs, this is resembling the classic woodland nightmare. More than being Dickens talking about lowlifes, the Wild Woods seem a nightmare version of J.K. Jerome’s Quarry Wood, «haunted… with the ghosts of laughing faces» (Three Men in a Boat, to say nothing of the Dog is one of the river stories often associated with The Wind in the Willows). It is worth noting that the forest is rarely a character in itself, in fairy-tales and folk tales: witches and cannibals dwell in them, sure, but without an encounter the worst that can happen is that you get lost (which is bad enough). What happens to Mole it is similar, with a horror twist more suitable to literature than to folk tales: this wood is more like Dante’s forest (weird beasts aside), almost directly quoted in George MacDonald‘s Phantastes. The closest picture you might have in your mind would be Snow White’s nightmarish forest scene.

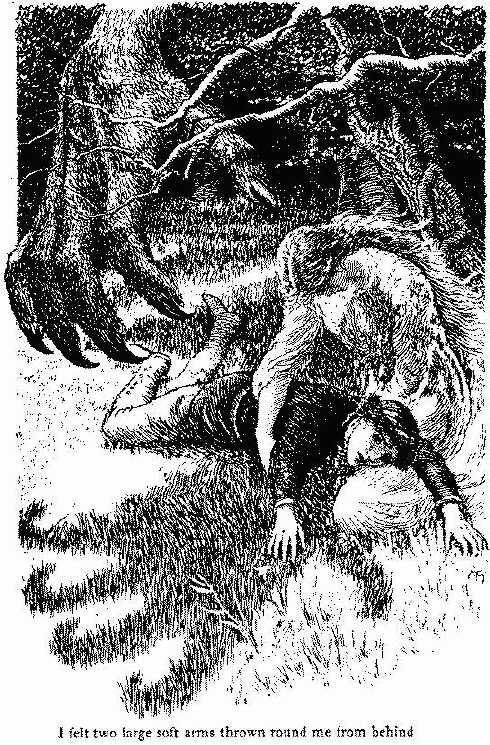

Our Mole starts running, strays from the path and of course this makes things worst: the only encounter he has is an equally terrified rabbit, until the whole wood seems to be chasing him and he collapses, terrified, within the dark hollow of an old beech tree.

So Anodos takes refuge in the arms of the maternal beech tree in George MacDonald’s Phantastes: ‘“ Why, you baby!” said she, and kissed me with the sweetest kiss of wind and odours.’

H. Carpenter, Secret Gardens: a study on the golden age of Children’s literature

And this is pretty much where we leave him, trembling under a blanket of dead leaves, because this is the moment when Rat wakes up, in the comfort of his well-furnished home, and finds that his beloved Mole has gone missing.

The most striking fact about the Wild Wood is that, despite its threatening nature, Badger dwells at the heart of it; and Badger is the most wise and perfectly balanced character in the book, with his gruff common sense, his dislike of triviality (he chooses to come into Society only when it suits him), and his strength of character which can–at least temporarily–master even the excesses of Toad. Badger is, of course, a portrait of a certain kind of English landed gentleman, but he is far more. He is the still centre around which the book’s various storms may rage, but who is scarcely touched by them.

H. Carpenter, Secret Gardens: a study on the golden age of Children’s literature

This is the point where Rat’s home, which started off as a hole in the ground, as another might have said, is described in detail as a human house: there’s a peg, from where Mole’s cap is missing, and an umbrella stand in the hall, there’s a fireplace. Both the Victorian furniture and the way Rat approaches the matter at hand, with a deductive method, have prompted artists like Wyndham Payne to dress Rat up like Sherlock Holmes, an impression Disney’s artist will take one step too far, as we have seen in the character sheet included in my previous article. All Grahame tells us is that Rat stappes a belt around his waist, with the sole purpose of fitting two pistols in it. Payne gives him laced boots and a fur overcoat, in front of a mirror with pegs that seem to be popping out of Sidney Paget’s illustration for 1893 Sherlock Holmes and he Crooked Man, published in The Strand Magazine, and Shepard keeps going along this line, dressing Rat as Sherlock Holmes four times out of seven. This is most likely what inspired Disney. We’ll have nothing of that too.

Rat goes into the Woods without any hesitation, armed with the two pistols and a «sout cudgel», the weapon of heroes in Norse folk tales and German fairy-tales when there’s no sword to he found (or when the sword is too much to be dealt with). He faces the same challenges Mole had to go through, but he’s the one to scare away nightmares, brandishing his cudgel and his valorous attire. Grahame goes as far as saying that Rat makes his way «manfully» through the woods and there’s no doubt he’s our Prince Charming, here to rescue poor Mole in Distress. He combs through the Woods, calling for his Moly, and at last he gets an answer. Mole is still hiding in the old beech tree.

Rat doesn’t resist to gently reprimand Mole for his foolishness and, in doing so, he gives us other details on the nature of the Wild Woods, both an enchanted place and the Slums to your Riverbank. It’s a place to be crossed in couples, and you need to know the way to navigate it.

…there are a hundred things one has to know, which we understand all about and you don’t, as yet. I mean passwords, and signs, and saying which have power and effect, and plants you carry in your pocket, and verses you repeat, and dodges and tricks you practice.

This has to be the first intrusion of what Tolkien would call Faërie in this deceivingly simple animal tale, an intrusion that will be quite preponderant when we’ll meet Pan himself.

While our favourite couple is resting, within the womb of the beech tree, snow starts falling down and transforms the Woods. One hand hand, the transformation is good: darkness leaves in favour of an enchanted glow, as if it’s suddendly no more night (which we know it is) but the downside is that Rat and Mole have to get moving, if they don’t want to be buried in snow while they sleep, or to freeze to death, and the snow is disorienting Rat. They loose the count of time, and loose themselves in the wood, until Mole stumbles upon something, as suggested by young Alastair through his governess’ letter.

Here, Rat behaves again a little bit like Sherlock Holmes: the accidental discovery of his sidekick doesn’t get overlooked and to Rat is the missing link in figuring out a solution to their predicament. The thing upon which Mole had fallen is no branch or root, because no branch or root could have done a clean cut such as the one Mole is nursing on his sheen, but has to be something else: it’s a door-scraper. Upon it’s finding, this is probably the first time we see Rat loosing his patience at Mole’s lack of understanding.

“…don’t you see what it means, you—you dull-witted animal?”

Scraping through the snow, they uncover a shabby door-mat, but still Mole doesn’t understand and insists Rat is making them loose precious time.

“Now look here, you—you thick-headed beast,” replied the Rat, really angry.

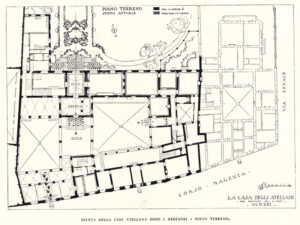

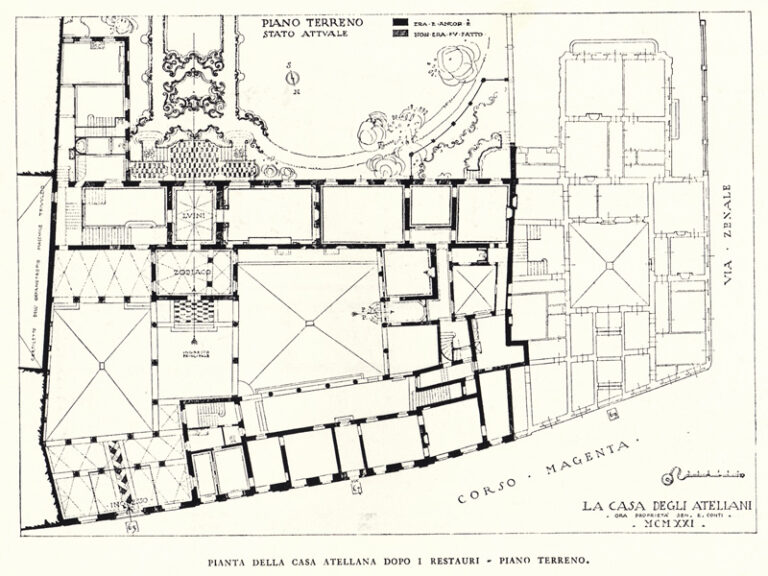

With more digging, they unearth a «solid-looking little door, painted a dark green. An iron bell-pull hung by the side», and below it, on a small brass plate, neatly engraved in square capital letters, they can read the letters Mr. Badger shining in the moonlight.

Astonished at his friend’s revealed power of deduction, and in fact more astonished than Watson has ever admitted to be, Mole pulls on the doorbell with all his might, while Rat bangs on the door. And this is where we leave them, hoping someone will answer.

1 Comment

Pingback:Mr Toad’s Motorcar – Shelidon

Posted at 11:55h, 01 May[…] to think of Mirkwood (I wrote about its connections with The Wind in the Willows’ Dark Woods over here), the encounter with the three feral (teddy) bears Archie, Teddy and […]