High Waters at Catfish Bend (a Mardi Gras story)

During the 1960s, around twenty years after building concepts and characters for what had become the Toad segment in The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr._Toad, at Walt Disney Studios they started working on two stories that are weirdly connected to The Wind in the Willows: the play Chantecler by Edmond Rostand, which was supposed to […]

During the 1960s, around twenty years after building concepts and characters for what had become the Toad segment in The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr._Toad, at Walt Disney Studios they started working on two stories that are weirdly connected to The Wind in the Willows: the play Chantecler by Edmond Rostand, which was supposed to be developed in the form of a ballet, and Catfish Bend by one Ben Lucien Burman, which I knew nothing about. So, naturally, I started digging. Since the first book of the series has a story whose core is taking place in New Orleans during Mardi Gras, I give it to you today.

1. Fox stories I should have caught sooner

I almost had a meeting with Ben Lucien Burman, figuratively speaking, when I first wrote about Badger in The Wind in the Willows: on that occasion, I briefly mentioned a couple of badger-featuring tales, particularly Beatrix Potter‘s The Tale of Mr. Tod (1912) and Fantastic Mr. Fox (1970) by Roald Dahl. Since I was focusing on the badger’s side, on that occasion I mentioned the tales of Br’er Rabbit as a possible influence on Potter, but I failed to mention that both stories are descending from a glorious tradition of stories featuring a fox, the Middle-Ages literary cycle of Reynard the Fox, which incidentally also features a badger named Grimbard (and which Disney thought about using for an animated movie around 1937). That was a bad omission, on my behalf, and it shows how rusty I am in talking about fiction, especially considering that Tolkien gave me an assist in this, in the portion I quoted here. Geoffrey Chaucer used these tales as sources for his “The Nun’s Priest’s Tale” in The Canterbury Tales. Alas, there was no badger, so I dismissed it from my memory.

Had I pursued that path, I would have found sooner both Chantecler and Ben Lucien Burman’s Catfish Bend series, as they both descend from the same tradition. They are both stories most likely to put us in a Carnival mood and, since that is approaching, I’ve decided to bring them to you as Sunday tales.

2. Ben L. Burman and a Wind in the Willows for the South

Ben Lucien Burman was born in Covington, Kentucky, in 1895 (on the same year, Oscar Wilde was imprisoned at Kenneth Grahame’s utter dismay). He became a journalist and wrote around 22 books, all of them defined, in his obituary on The New York Times, «affectionate portraits of the Mississippi and the Kentucky mountain region». His Catfish Bend series, comprising of seven stories, was illustrated by his wife, Alice Caddy.

The author… said he started writing on a toy typewriter at the age of 7

The New York Times, November 13th, 1984

The stories, set in the fictional town of Catfish Bend in Louisiana, are:

- High Water at Catfish Bend, 1952;

- Seven Stars for Catfish Bend, 1956;

- The Owl Hoots Twice at Catfish Bend, 1961;

- Blow a Wild Bugle for Catfish Bend, 1967;

- High Treason at Catfish Bend, 1977;

- The Strange Invasion of Catfish Bend, 1980;

- Thunderbolt at Catfish Bend, 1984.

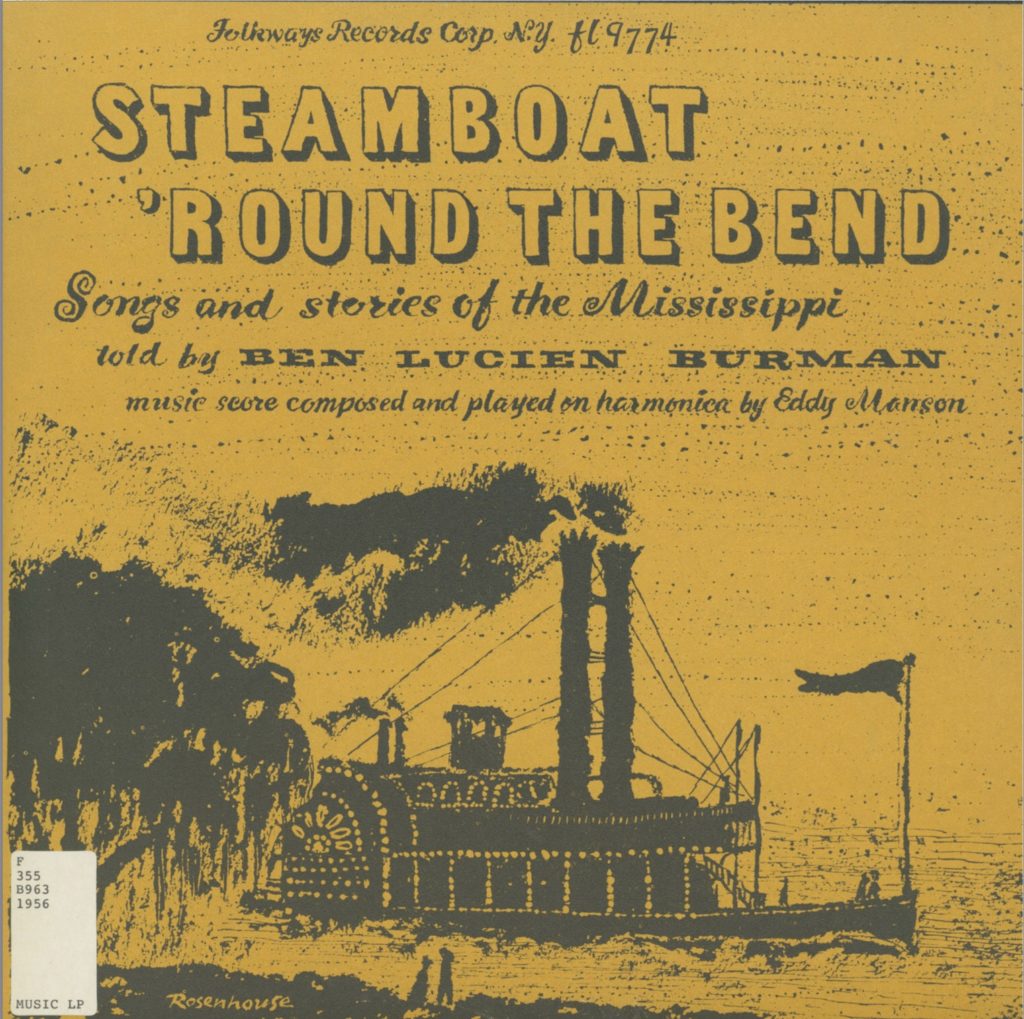

Far from being his only books, the author also worked on music, with his Steamboat ‘Round the Bend: Songs & Stories of the Mississippi, 1956.

The stores revolve around four main characters: a snake named Judge Black, a silly rabbit, a sporty fox, a musician frog, and a raccoon named Doc, the voice of reason, which is also our narrator as he tells the story to the author at the Catfish Bend stop of the Tennessee Belle riverboat on the Mississippi. In the first book, they are stranded on a small island in the middle of a flood and they form a truce in order to survive and save the riverside town. Most of the story revolves around the upholding of this truce and around their attempt to convince the government in New Orleans to build levees and prevent the floods in the bayou. You have some beautiful reviews on Goodreads.

Now for the bad news: the summaries and reviews on Goodreads are pretty much all you have. Some of the books were reprinted in the 1980s, but there are no modern editions available and there’s no digital copy (aside from a digital scan of The Owl Hoots Twice at HathiTrust). I myself had to buy a very used copy from overseas and I could only get my hands on the first title. But I’ll do my best to provide you with a more extensive summary and, if I can, I’ll try and do the same with some of the other chapters of the saga.

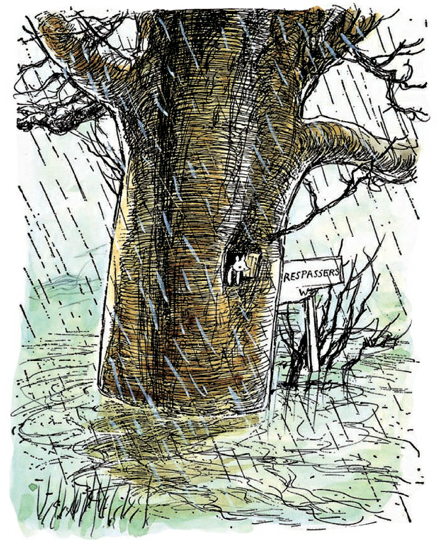

As I was saying, Alice Caddy illustrated the story with beautiful strokes of ink.

Below you can find a beautiful sketch of three of the main characters, taken from the third book of the series.

You can find all the illustrations for The Strange Invasion at this address, thanks to the efforts of one Michael Sporn who also came to the story through Disney’s failed attempt. I won’t be able to give you pictures of all the illustrations in the first volume unless I want to violate copyright, which I don’t, but I’ll try and give you the most significant: Caddy seems to be excellent in sketching situations and her drawings of the Mississippi boats and riversides are adorable little doodles, but she often fails in conveying (or willingly mitigates) and pathos and drama of some portions of the prose. The story is, after all, a story of animals who face certain death during a flood and who decide to put a hold on their urge of killing each other in order to do something about it.

3. The story

It was lucky for me that the Tennessee Belle stopped along the Mississippi to pick up some cotton just where she did that afternoon. If she hadn’t stopped, I never would have heard the truth about those queer things that went on in New Orleans.

This is how the tale starts, with our author waiting at the Catfish Bend stop, just below Vicksburg. And if Catfish Bend is a made-up location, Vicksburg is a quite real town in Warren County, Mississippi, currently home to three large posts of the US Army Corps of Engineers which, as we’ll see, are quite central to the tale. Though the time of this tale is never is explicit, Vicksburg was central during the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, serving as a gathering point for refugees, and the Waterways Experiment Station was installed in the town precisely following this event. But I better proceed in an orderly fashion.

Our author is waiting on the river when two raccoons approach, a young and an older one, and they start talking with each other. They are overlooking some of the work done by workboats of the Government Engineers, where «some men were building one of those big earth walls they call a levee, to keep the river from flooding and washing away everyone’s houses», and the two raccoons catch our author’s attention by mentioning something precisely in relation to that construction, basically an artificial embankment made of earth. Out author, however, is unable to figure out what the two are saying, because «you know the way it is when you want to hear something special: the people always stop talking».

The old coon sat there by himself, poking at an anthill with his paw. He looked friendly, ready for company, so after a while I went over and we started talking. He had a nice face, and honest, too. You knew right off you could believe what he told you.

Our author starts with a gentle touch, afraid of scaring him away, and this is pretty much the only place where we can figure out the author is human: the relationship between humans and animals, as we’ll see, is as touchy a subject as their dimensions in The Wind in the Willows, and Ben Lucien Burman deals with it with great grace. The raccoon asks him for a chocolate bar, seeing he has a paper bag with him, and the author gives him a big one, with lots of nuts inside, as he always has a chocolate bar when he rides on steamboats. Something I’ll keep in mind the next time I get a chance to ride on one.

It turns out our raccoon and our author have something in common, as the raccoon points out.

“I’ve seen you fooling around here on shantyboats and steamboats. I’m kind of a tramp myself”.

A line that can’t but remind us of the famous “messing around in boats” which was The Wind in the Willow‘s Rat ideal way of life.

The two shake hands on that, after which our raccoon washes his hands for almost a minute in the river, and then they start talking about the works being done around there to prevent the floods.

The Engineer boat began scooping earth from the river and piling it up on the opposite shore to make the levee higher.

It’s the chance for our author to ask the direct question and the raccoon admits that he was talking about that, and about how it wasn’t the humans who made the Government put up the works to stop the flooding, but in fact, it was the animals. Hence, Doc Raccoon proceeds to tell us the whole true story, from his point of view, and the author promises that he had faithfully reported it as he heard, only changing a couple of names at Doc’s bequest, as he wouldn’t have wanted to get some animals in trouble.

1. Stranded

The tale begins with our Doc Raccoon swimming for his life, during the most terrible flood ever. Though Alice Cuddy’s illustration shows us the Raccoon swimming quite comfortably in a lifebuoy, the description of the scene is really much more dramatic and bleaker, with Doc going inches from drowning and losing his life.

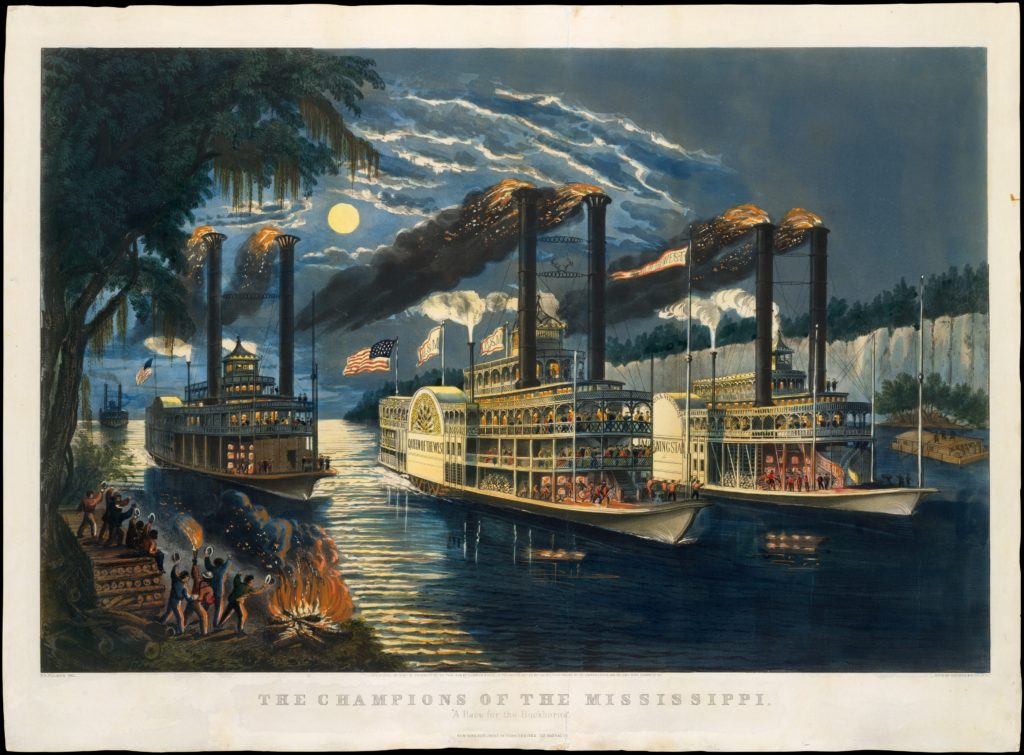

He eventually finds himself stranded on a mound of earth, with a gloomy frog and a quite anxious rabbit, and we meet two other main characters. The frog has a deep voice, «like the bottom note of a steamboat calliope», a musical instrument that, if you’re familiar with Carl Barks, you might know as the infamous instruments Donald Duck makes up his mind to play in The Price of Fame (in Italian it was called “fischiofono a vapore” and you can read about it here). Our Frog, as it turns out, is a musician too: he’s upset about the flood not for a special fear for himself (as we’ll see, he’s a very good swimmer), but particularly because they had started a «new frog Glee Club ad Indiana Bayou» and now the band was most likely dispersed all along the Mississippi: they had made him a leader and he had just finished tuning them just right. A Glee Club is basically a choir, mostly made by male voices, and Indian Bayou is also a real place in Louisiana. This idea of Mississippi jazzing frogs, as we’ll see, is something that also fascinated people at Walt Disney Studios for a very long time.

The other character is the Rabbit, and it’s clear from the beginning that:

a) our Raccoon has a way of reading people;

b) he’s reading nothing good in this particular fellow: he’s talking in a squeaking voice, always «giggling like a girl» (our Raccoon is a bit sexist, I suppose) and never stands still a minute but, most importantly, his tail reveals his true character. Here we have what we might call “Doc Raccoon’s Tail Theory” (and it’s hilarious that he uses the word “person”).

A tail’s the real way to tell a person’s character; a tail’s something you ought to use with care. I’m not so crazy about cats… but I will say they know how to handle a tail, slow, thoughtful. You can see with every swing how much brain there is behind it. The rabbit’s tail was going like a hummingbird’s wing all the time. You knew right away he didn’t have a grain of sense in his head.

Rabbits were not very highly regarded in The Wind in The Willows too if you recall.

We’re still on the mound when we meet our fourth character: a big black snake, four feet long, that is fighting against the water just as much as Doc had done in the opening of our tale. The frog and the rabbit are mightily frightened by this sight, as the snake is their natural predator, but Doc knows his snakes and sees that this particular one is nothing like a mocassin or a rattler (the first one is a viper and you might know it as cottonmouth, the second one is… well, a rattler). He elects to rescue him and brings him to safety with a long branch. Thus we make the acquaintance of Judge Black, from Grand Gulf in Claiborne County. Needless to say that that place is a real one as well.

Judge Black, who mostly speaks in mottos, introduces us to the central concept of the tale: the fact that in order to do his part and clean his name he became a vegetarian. This is not portrayed as something that comes either natural or without effort and, as a secondary crucial concept, Judge Black introduces to his “tell”: when he gets really hungry and he’s about to slip, his eyes «get fuzzy». As we’ll see, the idea of having a tell and sharing it with others in order for them to warn you, and being warned, is one of the most important messages of this tale: everyone has a weakness and is fighting his own battles, but the real mistake is doing that alone, pretending it’s effortless and doing it alone, not sharing it with others. For a children’s story, it’s a really powerful message about dealing with addictions and the general struggles of life, if you ask me.

The final character we meet is a sporty Fox, who arrives at our mount of earth more by navigating than by swimming. He’s a bit of a braggy character and doesn’t seem to have any idea of what’s appropriate, so much that he doesn’t seem to restrain from giving accounts of how good he placed in the last rabbit chase competition, in the presence of the rabbit himself. His name also tells the same tale: he’s called J.C. Hunter, Jaysee for friends. He’s also useful, as he’s the one prompting Doc Raccoon to think about forming a truce.

He was one of those sporty foxes, red-haired, and red-faced, and talked fast and loud. He looked like some of those smart-aleck fellows that come down to the swamps from Memphis and those other places to fish on Sundays, with their hair slicked back and wearing fancy clothes.

For now, we’ll leave them on the mound, trying not to get wiped away, working day and night to reinforce it, and meanwhile trying to get some sleep. Fox’s tail has a tell too, but we’ll learn about it in the next chapter. For now, let’s contemplate how in this tale the usual character of the Fox is turned around as not really working when it comes to properly function from a social point of view. Which is something I have to heartedly agree upon.

Quentin Blake was born in the suburbs of London in 1932 and has drawn ever since he can remember. He is known for his collaboration with writers such as Russell Hoban, Joan Aiken, Michael Rosen, John Yeoman and, most famously, Roald Dahl. He has also illustrated classic books, including A Christmas Carol and Candide and created much-loved characters of his own, including Mister Magnolia and Mrs Armitage.

Now, I would like to point out that I was able to visit that page on art.com and find that information only through Tunnelling because the website is closed to people visiting from outside the United States, and THIS KIND OF ATTITUDE SUCKS. You can read more about the collaboration between Quentin Blake and John Yeoman on this page.

Anyway, one really has to wonder what is with children and their fascination with floods, the most famous of them probably being the flood episode in Chapter 9 of the first Winnie the Pooh book (In Which Piglet is Entirely Surrounded by Water).

As it happens with that tale, the core of the concept is not navigating or swimming through the flood, as Pooh gets through rather effortlessly by trying to eat the bottom of one of his honeypots but being stranded away from your friends, and isolated, and calling for help in the somehow vain hope that someone will find your message in a bottle and listen to you. A concept I’m sure we can all relate to. In Milne’s story, Piglet goes through the whole ordeal of a friend coming but not really understanding his struggle (Owl and no wonder: the bastard can fly).

No one is coming in Burman’s tale: the animals are out for themselves and they have to use their talents at their best, and try to get along, if they’re willing to not only survive but strive.

2. The Truce

The idea of forming a truce is not prompted by looking at themselves, again, but by looking at others.

An you heard queer sounds all the time, sad sounds, steamboats out looking for drowning people or trying to get into a harbor, or animals going down on driftwood, calling out for help that nobody could give them, or birds flying overhead and chirping, looking for their nests and their babies they’d never see again.

The mound is getting smaller and smaller, eaten away by the flood, and Doc Raccoon knows they have to work together if they want to survive. This calls for a truce and, though he’s expecting resistance when he proposes to form one, no one dares object. His argument is that animals should have formed a truce when they came out from the Ark and, though I’m not a fan of introducing religious concepts into fables or fairy-tales (the dreaded Narnia effect), I have to admit that Burman does that with grace and delicacy, carefully avoiding the New Testament and just sticking to a part of the scriptures that might in fact be relevant for animals, just as much as Kenneth Grahame did when he described Christmas through the eyes of animals in the stables. Anytime one of the predators is slipping from their purpose (Judge Black’s eyes will get fuzzy, Jaycee’s tail starts thumping), someone says Ararat, thus evoking this idea of how the animals should have formed a truce back then when they came out from the Ark on the Ararat mountain.

You feel pretty helpless and lonesome when you’re on a tiny mound surrounded by hundreds of miles of flood water that’s eating away the earth you’re standing on by inches. It’s too bad everybody in the world can’t be on a little island the same way. Maybe they’d learn how to get along better.

Our animals stay on the mound for six weeks or so, each one doing what they do best: Doc does the washing because raccoons are good as that, and the Frog swims through the river retrieving food leftovers for everyone to eat; Jaycee uses his fox tail to sweep the place and Judge Black does the polishing, as his snakeskin is the best tool to do that, but the Rabbit tries to help everybody and is ineffective at pretty much anything (the poor thing). Nobody seems to be blaming him for that.

The one day we saw a whole family of chipmunks floating down on a log from a new washout somewhere. And I said it looked terrible to me that every year we had to go through these floods, with thousands of animals getting killed, and those that weren’t killed being driven out of their homes they’d been to so much trouble building, and taking their children somewhere else and having to start all over.

The river finally goes down and a resolution starts to form within the animals: they must convince the humans to go down to New Orleans and, in turn, convince the Government to do something about these terrible floods. It is always somehow blurred how animals are communicating with animals, and quite gracefully too: Doc only tells us that animals have a way of convincing humans to do what they want without them knowing it, farm animals in particular, and he’s confident that if farm animals and woodland animals unite their forces, there’s nothing they cannot accomplish. He also gives us a bit of wisdom about humans too, as humans come in two different varieties:

…tight-lid people and loose-lid people.

People who put their garbage lid on too tight, get their garbage scattered all over the place. Nice people, who leave nice things in their garbage cans at night, with the lid on not too tight, get respect from woods animals.

Unfortunately, our Raccoon goes to talk to an old grouchy horse about his idea of sending people down to the Government and is not too lucky, as countryside people have been there a great many times but the Engineers does not seem to care: one day they have to put up a wall against Gulfport against a hurricane, the other day they have to worry about the Panama canal, the other day they’ve got a problem with dockings at Houston. And the Major is no better: once they stopped flooding around New Orleans, nobody seems to worry anymore about the fact that the problem is far from being solved in the countryside.

3. The expedition

Animals decide they will go down themselves, accompanying the next expedition of humans (who, according to the old horse, are most likely to accomplish nothing), even though the rabbit is quite anxious about the voyage and all the possible (other) animals they might encounter during their journey. They take an old abandoned shantyboat at Two Mile Light and the frog goes down to the Indian Bayou Glee Club, to see if he can get the help of some of the other frogs down there. After all, everyone wants to sing in New Orleans. A shantyboat, if you’re wondering, is a bit of a rough houseboat, so we might expect a kind of journey that’s fairly similar to the (brief) one of Toad, Rat and Mole in Toad’s Gypsy Cart. The most notable shantyboat in fantastic literature is probably the one used by the Gyptians in Philip Pullman‘s His Dark Materials.

There’s no one on the boat, except some big black spiders, and Doc doesn’t want to be impolite so he tells them about the truce and their mission, but the spiders refuse to have any part in it, equally politely I must say, and wander off.

And that worried us a little, because spiders, like rats, know when there’s going to be trouble.

The frog rounds up a great deal of his Club fellows’ both female and male, and they set off: they encounter a terrible thunderstorm, which almost sinks them, and a horrible fog they’re able to navigate through by using the frogs themselves as a sort of radar system (and it’s amusing how frog gets all bully when in the presence of other frogs, a fact Doc Racoon doesn’t miss to highlight). Anyway, everybody enjoys a lot the frogs’ musical talent and they even sing a patriotic song together (My Country, ‘Tis of Thee, which I’m sure you know).

This is one of the longest segments in the book, where we get some beautiful descriptions of the riverside. Unfortunately, we also get the first betrayal of the pact and, as you might expect, it comes from Jaycee the Fox: one day, our boat comes across a field of watermelons and they are even able to strike a bargain with the big bull guarding the field, a rough big fellow with horns and red eyes. Unfortunately, the fox tricks them and tries to keep the watermelons for himself, but Doc catches him in flagrante delicto and, after denouncing him to the rest of the group, they basically give him the silent treatment.

Many a time after that he started talking, all smiling and friendly. And we all got up and walked away. And his eyes would get shiny and his body would shiver all over. It was really pitiful.

They pass lots of places, both real and fictional: Frogmore, there the frogs get all puffed up (there’s a couple of places called like that in Louisiana: but the most famous one on the Mississippi is probably the cotton plantation), Rabbit Hill, where is the turn of the Rabbit to get all excited, Rabbit Hash (enough to drown his excitement, as hash basically means “chop”). They go through Plaquemine, at the juncture of the Bayou Plaquemine and the Mississippi River, and through St. Rose, on the east bank of the Mississippi.

They try and dock near the highway bridge, which is probably the Huey P. Long Bridge, a cantilevered steel truss bridge carrying the U.S. Route 90 through the Mississippi River, built in 1935 by the immigrant civil engineer Ralph Modjeski (to reinforce the concept that «immigrants get the job done») and designated as a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark, not to be confused with the homonymous bridge in Baton Rouge.

Unfortunately, they get caught in the rapids and are only saved by a heroic act by Judge Black, who acts as a rope at the risk of ripping himself in half. It’s the second time we see him acting this way (the first one being a moment when the rabbit falls overboard and he scoops him up from the water). Through the eyes of Doc Racoon, «it was a wonderful thing of him to do». It’s not like our Racoon gets excited easily.

They eventually see a rope on the deck of another boat, docked under a tree, but the boat is guarded by a dog and the dog is too plagued with flees to pay any attention to them. In the end, it’s the Fox who redeems himself: he promises to show the dog how to get rid of the fleas if he tosses them the rope, and so he does, and they’re able to revive Judge Black with some Bay leaves.

To everyone’s surprise, the Fox keeps his word too and shows the dog a neat trick to get rid of the fleas without even killing them (it involves deep diving with a leaf for the fleas to crawl upon if you’re interested). The trick actually works and the dog tells all the other dogs around, so in a minute the river is full of dogs swimming and getting rid of their fleas, and they make sure to go back to their houses and come back with the best things they can find to eat.

We had a wonderful time. And of course we knew it was the Fox that had done it, so we forgave him, and took him back to the pact.

4. Down in New Orleans

The animals arrive in New Orleans at last and wait for their countryside humans to catch up. The city immediately presents itself as chaotic, inhospitable, and with very little to eat, as one might expect.

“Never saw such terrible people. They freeze their food and burn their garbage”.

The countryside people go to try and talk with the Army Engineers, but with no luck, as they’re told that the General is up in the Countryside for some urgent business and will not be back any time soon. They are then granted an audience with the mayor. We have no name for this mayor, of course, as many of the conversations between humans are reported through the eyes of Doc who’s lurking and sneaking in the background: we just get the description of a «sleepy-eyed, bald-headed man with a big fat stomach» and Doc cannot but think about how the veterinary is able to fix something for the cows when they seem to have troubles like that.

However, even if we don’t assume that we’re looking at the aftermath of the 1927 flood and not the one of 1874, I thought you might find it interesting to read the story of major Arthur O’Keefe, a guy who, in 1927, agreed with the head of Canal Bank James Butler to blow up with dynamite a levee upstream in order to cause a crevasse (which is precisely a levee failure), flood the country and guarantee the safety of New Orleans. You can read an article here.

Anyway, humans have no luck with the Army Engineers nor with the mayor, as usual, and as the stable horse had predicted, and the woodland animals find them consorting angrily on a porch.

It was dark by then and they just sat around on the porch, without even lighting a lamp, and when people do that, you know things are bad.

Everyone wants to go back to the valley, but our Racoon stays up through the night and studies the city, without anger nor disdain, even admitting that the lights can be pretty (though he still prefers the stars). He sees people going about in fancy costumes and bands moving throughout New Orleans, in preparation of the great party of Mardi Gras.

And I remember how all my life I heard from the animals down the river how Mardi gras is the biggest thing in New Orleans.

It is indeed. Celebrations in New Orleans happen throughout the two weeks preceding Ash Wednesday and the culmination of these celebrations is the parade during the last day, Mardi gras (I talked about it briefly when I talked about Carnival here). The parades are organized by groups known as krewes you might be familiar with if at least you paid attention while watching Cloak and Dagger: the oldest krewe is the Mistick Krewe of Comus, founded in 1856 and whose inspiration from the name comes from John Milton‘s Comus (a guy we have already encountered while talking about Arthur Rackham‘s illustrations to the masque); the second oldest one was the Knights of Momus, established in 1871 and disbanded during World War II; the third oldest krewe is the Krewe of Proteus, founded in 1882 named after the shapeshifter god of the seas. Since there’s mention of a King and Queen of Carnival, however, the reference we’re seeing here is to the Rex parade, though a big part of the whole parade is the secrecy for the identity of the king and queen and they seem to be failing spectacularly at that, since our Racoon is able to identify them on the spot.

In looking at how much people care about Mardi Gras and the effort they’re putting in to organize the party. Racoon concocts a plan to make sure people will listen to the countryside’s plea.

If the New Orleans people wouldn’t help get the levees fixed at Catfish, we would stop their Mardi gras.

The way they carry on their boycott is simple: by destroying people’s sleep. They round up as many raccoons and foxes as they can round up and they start running up and down gardens and fences, making a terrible noise and driving the city dogs crazy (dogs who have never smelled a wild animal before). They target with particular viciousness the important people from the parade and the mayor’s house, who has «one of those brown, nasty little dogs [with] a face all wrinkled like a potato and a squawk like a chicken». They keep at it for several nights, until everyone in the city is wandering around half-asleep, nervous and jumpy.

Well, after a week everybody in New Orleans was so worn out work on the Mardi gras almost stopped. And there were big stories in the papers about the wild animals coming into town, and wondering what made them act that way.

The farmers are no fools and jump to this chance: they go again to talk to the mayor and try to explain to him that the animals are clearly driven out from the countryside by the high waters and the floods, and if animals are that nervous one can only wonder how nervous people might be, but the mayor again refuses to act.

After raccoon and foxes, it’s time to up the game: it’s Judge Black’s turn to go into the countryside and rally up his fellow snakes, and Judge Black is one who doesn’t speak often (and always does so in mottoes) but knows how to make himself heard. He comes back with a horde of snakes and, of course, everyone likes to sleep just as much as no one likes to do so with snakes roaming around.

Next day when the New Orleans people woke up, every place they went was full of snakes – green snakes and red snakes and black snakes and yellow snakes, snakes crawling up the kitchen sinks and sometimes in the beds. And plenty of ’em weren’t nice snakes like Judge Black.

Unfortunately, the snakes do not help either: the next day the farmers go again to the mayor, and the next day they get the same answer.

If you’re familiar with Italo Calvino‘s work, in one of his “Invisible Cities” the people go through a similar ordeal: by destroying the natural order, they find themselves facing animals unleashed by the absence of the previous link in the food chain. The wonderful watercolor above depicts precisely that city, Teodora, and was created by Colleen Corradi Brannigan, who has a whole project dedicated to Calvino on this website.

Anyway, it’s the frog’s turn, now, but not in the way you might expect. Instead of storming the city, the frogs adopt a more subtle approach: they go on hunger strike. And frogs, on the Mississippi bank, mostly eat mosquitoes. After a few days of the strike on the frog’s behalf, the rabbit wakes up to a terrible smoke coming from the countryside, only to realize it’s not smoke at all: it’s a swarm of mosquitoes heading towards the city. The situation is terrible and, at this point, of Biblical Plagues’ proportions: people cannot rehearse their Mardi gras music and dances, and they start to wonder if this is not some kind of punishment. The shadow of having to cancel the celebrations is looming, as the floods get worst and worst, and people in the city even go out suggesting to the mayor that maybe if he helped the people from the countryside their luck would change. But, as the Pharaoh of old, the mayor would not change his mind.

5. The final ruse

After being refused over and over, people from the countryside start to talk about leaving again and Doc Racoon is thinking and studying more than ever, as every moment he sees more animals coming down the river, being swept away from their homes by the terrible floods upstream. Eventually, he sees a group of muskrat and, in great secrecy with Judge Black, he decides to go talk to them. We are never explicitly told, but it’s clear enough that Doc asks them to chew holes in the levee in New Orleans since, as the countryside and Mardi gras people are going through yet another audience with the mayor, water starts flooding the streets of the city.

People are not used to floods anymore, so they start panicking, but the countryside people know very well what to do and they start piling bags of sand and building additional dams to face the emergency. Eventually, being reminded what’s like to be flooded and as thanks for saving New Orleans, the mayor meets with the farmer and grants their requests to start working on stronger, more efficient levees upstream. They are invited to stay for Mardi Gras and take part in the parade, and it turns out to be the best Mardi gras ever.

New Orleans people are really nice. They just had to be reminded… I guess most people are that way, a little slow in the head, like the muskrats. You can’t expect everybody to be smart as a raccoon.

4. Walt Disney’s abandoned project

Contrary to other abandoned projects, resources on Catfish Bend are scarce: on-line, you can read about it here, here (it is number 11), and here (it is number 10); in books, there is something about in one of They Drew as They Pleased volumes, specifically the one talking about Walt Peregoy, so let’s start from him.

Walt Peregoy was a rather peculiar character, highly egocentric, and with such a conception of his own artistic talent to take up a rivalry with no other than Eyvind Earle while he was just one guy charged in painting backgrounds for Sleeping Beauty. His first important work, however, was in styling the backgrounds for One Hundred and One Dalmatians, and lots of the unusual, modernist stuff you see going on there is probably due to Peregoy’s hand and, according to his own recollections, that’s precisely the reason art director Ken Anderson had chosen him: to create something original.

Walt Peregoy’s sense of colour was unparalleled at the Disney studio. His backgrounds were a visual feast and his most progressive colleagues like Ken Anderson and Rolly Crump loved them. But Walt Disney did not share their enthusiasm and ultimately disliked the modernistic look and feel of the movie.

– Dider Ghez, They Drew as They Pleased: The Hidden Art of Disney’s Mid-Century Era

After working on the weird and rightfully little-known short The Saga of Windwagon Smith, released in 1961, he remained in charge of styling the backgrounds for The Sword in the Stone but gradually lost influence and control, as Walt Disney really didn’t like the way he was pushing boundaries of what was considered to be the studio’s style.

He progressively fell from grace and, even if Ken Anderson still liked his work and supported projects like Chanticleer and Catfish Bend (Peregoy worked on both), none of his concepts were approved.

In January 1965, after all, his proposals were shelved, he left the studios. He went on doing backgrounds for Hanna and Barbera, including Dastardly and Muttley in Their Flying Machines so: yes, if you see similarities, you’re right.

Exits Peregoy enters Ken Anderson, who – as we were saying – was an art director at the time, had sponsored him and supported him a lot (and, as we’ll see, will continue to do so). Anderson saw Ben Burman as a modern Mark Twain and, around 1973, was vehemently supporting the project of putting it on the big screen, up to the point of becoming an obsession and influencing lots of other projects. As a former character designer, he was deeply fascinated by the animals populating the tale:

Doc Racoon, the country squire, well-liked by all, leader of the good guys; the snake Judge Black, the solemn, motto-quoting pundit of great and unimpeachable integrity; J.C. Hunter, the flashy show-off red fox whom Ken converted into a hillbilly entertainer; and Gray Fox, the con man, riverboat gambler villain.

– Didier Ghez, They Drew as They Pleased: The Hidden Art of Disney’s Early Renaissance

From these character designs (and not because anyone bothered to tell us), we can deduce that they were in fact working on material that was also taken from the third volume of the series, where the grey fox infiltrates the community with his rat sidekicks and tries to take away the birds’ eggs.

Peregoy too came back in 1974, to be head of the background department, and lots of the work he did on Catfish Bend somehow got poured into The Rescuers: the same Louisiana feeling, sceneries, even some of the characters such as the field-mouse lady. The Rescuers, which I find to be a delightful and highly underrated movie, it’s the closest you’ll ever come to seeing a Disney cartoon from Catfish Bend. Peregoy didn’t last long, however, and was sent to work on concepts for Disneyland.

Still, Ken Anderson didn’t give up on the project. By 1976, helped by Dave Michener and Steve Hulett, he produced different outlines for a possible story and even invited the author to visit the studios, a visit that took place around June 1977.

You can read Steve Hullet’s point of view in the book Mouse in Transition: An Insider’s Look at Disney Feature Animation, particularly in chapter 4, “And Then There Was…Ken!”. Hullet provides a non-edulcorated view of what working in the studios was like since the very beginning, in which we see him and Don Duckwall «exchanging insincere smiles».

“Ken Anderson is working on a project based on a book called Catfish Bend,” Don said. “He needs a writer. I thought this would be a good chance for you to show us what you can do.”

From the way Hullet writes about it, it seems far from being a promotion: he was working on The Fox and the Hound with Larry Clemmons, the writer behind The Jungle Book (1967), The Aristocats (1970) and Robin Hood (1967), and Woolie Reitherman, one of the so-called “nine old men” of Disney’s. That was considered an “A” feature and Steve wasn’t so keen on leaving it before it was completed, but he knew better than to argue.

Ken Anderson himself was coming out of a big project, the animated parts on Pete’s Dragon.

It turned out there wasn’t just one Catfish Bend book, but three. They were populated with eccentric characters akin to Bre’r Rabbit, Bre’r Fox, and Bre’r Bear in Song of the South. All the characters were swamp and river critters living along the banks of the Mississippi: a raccoon, rabbits, turtles and snakes.

By this time, Ken was trying to put together some of the longer sections for the novels and to build a rough continuity between various episodes. If you take a look at some of Disney’s work, the very idea of “containers” (package/anthology films) such as The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad show that one of the challenges apparently was to have enough material for a full-length feature. It is unclear where the problem came from, but the story department that was created with the very purpose of selecting stories before an effort was put into them, was clearly failing in its purpose.

There was lots of good stuff, also lot of repetitive and unfocused stuff. But he described all of it to me with relish, ending with: “Steve, you and I are going to develop a feature so rich, so compelling, that the studio will have to put the picture into production. The company won’t have any CHOICE but to greenlight it.”

Ken Anderson and Steve Hullet start working on the project and putting together what was called “a treatment”, which is the concept document for the plot of a movie (see here), and in their case, it’s described as a sort of collage of pieces created by cutting pages away from the books. The lead of the story was of course the raccoon, and the story was starting in the flood of the Mississippi River of the first book I just talked to you about. Then, by drawing from different parts of the books, they introduced three sets of villains: city rats, river rats, and weasels that were modeled in a way that was similar to Disney’s adaptation of The Wind in the Willows. Unfortunately, Ken Anderson’s work hadn’t been found appealing by the studios and Steve Hullet found himself unable to deviate much from what the colleague (and supervisor) had previously done. One of the problems was about the villains, which were too many and too similar to each other, and equally drawn from the subsequent books (as we have seen that the first one has little if no villains at all).

Steve Hullet’s attempt to change the story and simplify its many twists and turns results in a bad argument with Ken Anderson: Hullet is put back on The Fox and the Hound.

Ken was also, I decided, a fourteen-karat prick.

– Steve Hullett, “Mouse in Transition”

Eventually, when Anderson retired in 1978, the project was still waiting for a green light.

In July 1978, a few months after Anderson’s retirement, we have reports of a meeting between Woolie Reitherman, the same Steve Hulett who had worked on (and been kicked out of) the project, and Mel Shaw, in which they tried to summarize the plot outlines on the table. One idea had the young daughter of a poor family discovering the animals jamming jazz on the riverside. Another plot saw the daughter of a rich plantation owner being swept away in a flood, only to be saved by our group of animals.

Mel Shaw dived into the subject and, the next month, presented one more outline plot, featuring the daughter of an evil circus owner fleeing her home and ending up living with the animals of Catfish Bend. The meeting was held between Shaw himself, Brad Bird, and Randy Cartwright, in front of Ron Miller and Steve Hullet himself, apparently unable to shake free from the project. Apparently, no one was particularly convinced of this new angle, but the movie was scheduled for 1984, six years later, after The Fox and the Hound and The Black Cauldron, so they thought they still had time to make it right.

They never did.