I have had the occasion of bringing you some stories, recently, that came from my love for legends and myths, sure, but mostly from my love for the Danish artist and illustrator Kay Nielsen. He was an absolute genius and I started talking about him here. Kay Nielsen isn’t the only artist I love to pieces and he isn’t the only one who has a deep influence on what I read and write (I also write fiction, although not on these pages): I also have a tremendous passion for Arthur Rackham. You have seen some of his works pretty much every time I had the chance of showing them to you, as he also illustrated a great deal of fairy-tales, Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens and The Wind in the Willows. So I thought I could dedicate some words to him as well.

The Golden Age of illustration

Between 1880 and 1920, a series of fortunate events and circumstances created the perfect setting for the flourishing of illustration, both on books and magazines, both for children and adults (but, as we’ll see, especially for children): advances in printing and engraving technologies permitted a more accurate and a less inexpensive reproduction of artworks, in higher numbers, and the public started demanding these kinds of products. In addition to this, the Industrial Revolution had created a new middle-class, which meant more people willing to buy books for themselves and their children. The downside of this could have been the dramatic increase of moralistic works, with highly educational illustrations, meant for virtuous children who would eventually grow up to kill their parents. Luckily enough, children’s literature had started with parents amending gruesome fairy-tales for their own kids, in the attempt of not ending up murdered by them. One of the first works setting the basis for what will become “the Golden Age of illustration”, especially for children’s literature, is considered to be George Cruikshank’s illustrations for German Popular Stories: it’s 1824 and it’s the first time a prominent and affirmed author takes his time to create illustrations for a children’s publication. There’s still a moralistic angle, especially considering that he was also illustrating Charles Dickens, but we’re saved by the appearance of works such Edward Lear’s Book of Nonsense (which he illustrated himself, as you can see below) and Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland which he first illustrated himself, before approaching John Tenniel under the advise of Carroll’s friend George Macdonald.

There was a Young Lady of Clare,

Who was sadly pursued by a bear;

When she found she was tired,

She abruptly expired,

That unfortunate Lady of Clare.

The arts and crafts movement, with its attention to graphic design as we consider this today, only gave additional fuel to this phenomenon and a series of artists, inspired or proper part of movements such as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, came to define the imagination of thousands of readers. Some of these artists are my favourites: Walter Crane (see his Edmund Spenser‘s Faerie Queene, the illustration to William Morris‘ The Story of the Glittering Plain, The Happy Prince and Other Stories by Oscar Wilde), Edmund Dulac (see his Stories from The Arabian Nights, William Shakespeare‘s The Tempest, The Sleeping Beauty and Other Fairy Tales, Stories from Hans Christian Andersen), and Aubrey Beardsley (a man who was absolutely revolutionary with his illustrations to Sir Thomas Malory‘s Le Morte d’Arthur, and Oscar Wilde‘s play Salome), alongside Arthur Rackham and Kay Nielsen themselves.

In the United States, the style and characteristics of the “Golden Age” is connected to the Brandywine School, founded by Howard Pyle. The most significant members of the movement overseas are considered Jessie Willcox Smith (whom we might have already encountered for his illustrations to Robert Louis Stevenson‘s A Child’s Garden of Verses), Maxfield Parrish (another genius) and N.C. Wyeth (highly considered, and in my opinion greatly overrated).

A vast selection of artist who participated at the Golden Age of illustration can be found here.

Enters Rackham

Arthur Rackham’s work is considered to be the culmination of the Golden Age of Illustration in Britain. One of no less than 12 brothers, he studied part-time at the Lambeth School of Art while he was working as a clerk at the Westminster Fire Office, and very soon left that occupation to start working for the Westminster Budget as a reporter and illustrator. There’s evidence of his first work being some illustration to some Thomas Rhodes‘ To the Other Side in 1893, but I have absolutely no idea what Rackham’s contribution was. It’s supposed to be a voyage thing, it has maps and everything, but this is pretty much everything I know. For the Westminster Gazette library, the first work with his name on the cover were the illustrations to The Dolly Dialogues by novelist and playwriter Sir Anthony Hope Hawkins, which you can read here. They are essentially dialogues, as the title suggests, between witty Dolly and some other characters.

It’s 1894 and it’s pretty much the moment when Rackham’s career takes flight: illustrations for books will be his main occupation for the rest of his life. Following, I try to summarize in chronological order some of the works Rackham worked on, and how he defined the way we picture them in our minds.

1. The Ingoldsby Legends (1898)

The Ingoldsby Legends, or Mirth and Marvels is a delightfully varied collection of short stories, myths, legends, ghost stories and poetry, supposedly written by one Thomas Ingoldsby of Tappington Manor, pen name of Richard Harris Barham, a clergyman from Canterbury. They had been published in 1837 as regular series, firstly in the magazine Bentley’s Miscellany (an English literary magazine founded by Richard Bentley) and later in New Monthly Magazine, founded by Henry Colburn, the same magazine which had published John Polidori‘s first gothic novel The Vampyre in 1819. The Ingoldsby’s stories were highly popular since the start and were collected in books published in 1840, 1842 and 1847 by the same Richard Bentley who had firstly published them. Before Arthur Rackham approached them for the 1898 edition, they had been illustrated by artist like John Leech (the first illustrator of Charles Dickens‘ Christmas Carol in 1843), George Cruikshank (already mentioned as possibly the first illustrator to turn his attention to children), and John Tenniel (Lewis Carroll’s first illustrator after himself, if you recall).

The second edition of Ingoldsby Legends illustrated by Arthur Rackham, currently to be found on sale here (and way above my current budget).

Barham’s work is not the fork of a folklorist: even if some stories are collected from Kent’s lore, most of the works in the collection are reinterpretations, often humorous, as it’s immediately clear from the introduction to the collection.

The World, according to the best geographers, is divided into Europe, Asia, Africa, America and Romney Marsh.

Rackham’s illustrations were originally created in 1898 and revised and coloured in 1907 (you can see the date in some of them), but were published only in 1908.The stories illustrated by Rackham in colour plates include:

- “The Leech of Folkestone: Mrs. Bothersby’s Story” (here);

- “A Lay of St Nicholas” (here);

- “The Babes in the Wood, or the Norfolk Tragedy” (here);

- “The Lay of St. Cuthbert, or the Devil’s Dinner Party: A Legend of the North Countree” (here);

- “A Lay of St. Dunstan” (here);

- “The House-Warming” (here);

- “A Lay of St. Gengulphus” (here);

- “Grey Dolphin, a Legend of Sheppey” (here);

- “Sir Rupert the Fearless: a legend from Germany” (here);

- “The Lay of the Old Woman Clothed in Gray” (here).

There’s also some beautiful inked illustrations, but in order to bring them to you properly I would have to dedicate a whole post to the strange and weird Ingoldsby Legends, and though this might happen, this is not the day.

2. Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm (1900)

In 1900, while he was also working on Gulliver’s Travels, Arthur Rackham was also called to illustrate a special edition of Grimm’s Tales, translated by Mrs. Edgar Lucas and published by Freemantle & Co in London. His work is mostly black and white, and you can’t really say you know and love Rackham if you’re not familiar with his inkwork. Among the tales he illustrated, we find “The Golden Bird”, “Jorinda and Joringel”, “Hanse and Grethel”, “Tom Thumb”.

These illustrations were too revised and coloured, through the many reworkings and the many times, once for the additional publishing in 1909 and another when they were republished in a collection known as Snowdrop & Other Tales by the Brothers Grimm (1920). Some of the works are title pieces, like the one provided above. Others are full plates and they ore the ones that will be reworked in colour (Rackham will do no less than forty of them).

Some of the stuff is highly decorative, with elements from the stories becoming intricated patterns very much in the Arts and Crafts Movement style.

A few years ago, Jeff A. Menges has curated a collection of such black and white works, called The Fantastic Line Art of Arthur Rackham, which has a very extensive selection of these little-known work, but unfortunately falls short in providing context and references.

3. Rip Van Winkle (1905)

Rip Van Winkle is a short story from 1819 by Washington Irving, and possibly his most famous short story, alongside The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (1820). It tells the story of a Dutch-American villager who falls asleep in the Catskill Mountains, at the charm of a mysterious Dutchmen, and wakes up twenty years later. Trick is he fell asleep just before the American Revolution and, as such, he wakes up in a much changed world. It was firstly published as a part of the serial collection The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent, between 1919 and 1920, and attributed to the fictional Dutch historian Diedrich Knickerbocker. It is essentially a ghost story.

Arthur Rackham provided the first coloured illustrations (in the amount of fifty-nine plates) for the edition published by William Heinemann in 1905, and this earned him the public eye. His relationship with the published will be long-lasting and Rackham started exhibiting annually at the Leicester Galleries. His fame would only grow when he’ll be called to illustrate Peter Pan in Kensington’s Gardens the following year. In 1928 he will come back to work on The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.

4. Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens (1906)

Following his work on Rip Van Winkle and his first exhibitions for the Leicester Galleries, it was the galleries themselves who arranged a meeting between the artist and J.M. Barrie, who had already published The Little White Bird in 1902 and, following the great success of his play about Peter Pan in 1904, was receiving pressures to extract chapters 13–18 and publish them autonomously. Rackham will do fifty full-page illustrations for what was being conceived as a gift book and the admiration between the author and the artist was mutual: Barrie said that Rackham’s work “entranced” him, and Rackham would never cease to quote Barrie’s Kensington Gardens as a wonderful place to set a myth.

Never Never lands are poor prosy substitutes for Kaatskills & Kensingtons, with their stupendous powers of imagination. What power localizing a myth has.

In these colour plates, Rackham often chooses to illustrate atmospheres, rather than specific scenes, thus complementing what’s being narrated. It’s perhaps the most revolutionary aspect of his approach to illustration. See for instance the picture above: it comes at a specific point in the text where it’s said that the fairies cannot dance until the Duke remains without a wife, because they are sad and when fairies are sad they forget all the steps of their dances. Rackham chooses to show them in happier times and his choice doesn’t contradict the text: it reinforces it by providing comparison with a happier times.

Another fitting example is when Peter meets Maimie (Wendy’s precursor), and Rackham chooses to illustrate the side text, instead of showing us the main scene.

There’s a couple of essays in Rackham’s work within The Annotated Peter Pan (The Centennial Edition) published by W.W. Norton & Company and curated by Maria Tatar. Particularly it features the essays:

- Arthur Rackham and Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens: A Biography of the Artist;

- An Introduction to Arthur Rackham’s Illustrations for Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens;

- Arthur Rackham’s Illustrations for Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens.

Although the text is not included in the publication, all 51 illustrations are richly commented in detail. Some of these plates are legendary and have forged our imagination on what Tolkien would call Faerie.

“Rackham seems to have dropped out of some cloud in Mr. Barrie’s fairyland, sent by a special providence to make pictures in tune with his whimsical genius”

– Pall Mall Gazette

He will also do some black and white work for an enlarged version, alongside a new colour frontispiece, for the reprint of the book in 1912.

5. Puck of Pook’s Hill (1906)

In the same year that brought him to fame with his work on Peter Pan, Rackham also worked on the first American edition of Puck of Pook’s Hill, a rather little-known fantasy book by Rudyard Kipling, a collection of short stories spanning throughout different times of English history. Framed as stories within a story, they are mostly narrated by historical characters magically evoked by Puck, “the oldest Old Thing in England” in his own words. It feels a bit like a season of Dr Who: some of the stories are historical, others are supernatural, others are plain nonsense. Harold Robert Millar had worked on the illustrations for the British edition, also in 1906. Rackham did four colour plates: one of them is often used on covers of modern editions, as it features Puck himself telling the stories to the two children of Burwash.

6. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1907)

Firstly published in 1865 by Charles Dodgson under the pseudonym of Lewis Carroll, it is one of the works defining children’s literature for the best. The work was visually known through the work of John Tenniel, with his 42 wood engraved illustrations, but 1907 was a favourable year for new illustrators to try their hands at reinventing and reinterpreting the characters and situations in the book: it’s the year Macmillan’s exclusive rights to the book expired. Charles Pears and T.H. Robinson did an edition in this year, Bessie Pease Gutmann and Millicent Sowerby did illustrations for editions in the US, and Harry Rountree did another, which will be published the following years. Around 20 new editions appeared between 1907 and 1909. Before them, it’s also worth mentioning Blanche McManus for the first American edition, and Peter Newell for a 1902 US edition.

Rackham work was published by William Heinemann in a limited edition of 1.130 copies (alongside a smaller trade edition), and includes a total of 13 colour plates and 15 linework illustrations. His work is incredibly dynamic and always tries to convey the sense of overwhelming oppression that permeates Wonderland: a crowd of animals is always ready to jump on our poor Alice, who’s running, falling, swimming through the utter nonsense of her own mind. Rackham’s work was revolutionary in more than one way and you can read about it here.

«To subsidize the higher cost of preserving the integrity of his artwork in print, Rackham partnered with the publisher William Heinnemann and they came up with a profitable model — each book was issued in a small limited-edition run of signed, beautifully bound, expensive copies, and a large run of affordable mass-market copies.»

– Maria Popova, “How Arthur Rackham’s 1907 Drawings for Alice in Wonderland Revolutionized the Carroll Classic, the Technology of Book Art, and the Economics of Illustration”

7. The Land of Enchantment (1907)

There’s not much I can tell you about this book, aside from the fact that it was published by Cassell in London, and contains stories originally published in ‘Little Folks’. These stories are attributed to one Jeanie Lang in The Fantastic Line book (which I don’t trust very much, to be honest), and to A.E. Bonser, B. Sidney Woolf, and E.S. Buchheim by this website, which has the book on sale. B. Sidney Wolf is most likely referring to Bella Sidney Wolf, Virginia’s sister-in-law, who indeed authored stories for Little Folks – The Magazine for Boys and Girls. I have zero ideas who the other guys are supposed to be and I have very little information on the stories included in this book. No, I’m not going to spend £ 65 to find out. Rackham’s illustrations seem to be both full-page plates and small inserts and inkworks, all in black and white.

The Fantastic Line of Arthur Rackham includes twelve illustrations from this book:

- “I want none of your leaping and dancing now”, featuring a fisherman sitting on top of a rock, with fishing nets and fishes at his feet and brandishing a flute;

- “All through Egypt every man burns a lamp”, with the sun setting on cats and the sphynx;

- “Special food was prepared for him”, with a crocodile and a goat which is not going to end very well;

- “Then was the thief’s opportunity”, with crows, a donkey and a rather distressing first-person point of view on gallows;

- “A swarm of field-mice gnawed the quivers and bow-strings”, with mice boycotting what looks like a Roman or a Greek army;

- “Cambyses and the Arabian king pledged faith with each other”;

- “Sigurd pierced him with his sword, and he died”;

- “Once again the buzzing fly came in at the window”, with a dwarvish figure working in a forge;

- “He raised his hammer with a mighty swing”, featuring a guy slaying a giant;

- “Hymir rushed forward and cut through the line”;

- “There broke forth a wailing and a lamentation” (no idea what’s going on here, but somebody’s dead);

- “Held a cup to catch the venomous drops”, where a woman holds up a cup to catch the venom that’s dripping from the mouth of a snake into the one of a guy chained to a rock, and I know I should know where this comes from.

I give you number two.

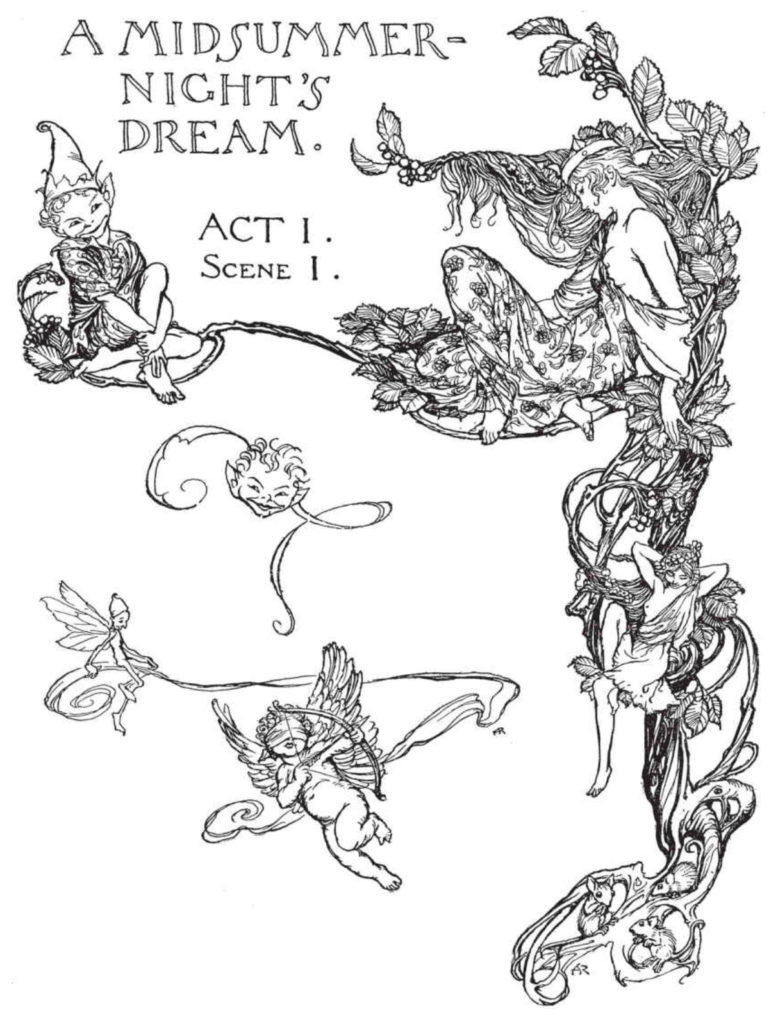

8. A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1908)

While he was publishing his work for Alice in Wonderland, Rackham started working on illustrations for Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, edited by the same published, and no one had any doubt about him being the man for the job, at this point: the result will be 40 colour plates and 34 inkworks, speaking from the subtext in the very same way Rackham had interpreted and complemented Barrie’s Kensington Gardens. The work had already a tremendous success not only as a subject for illustrations, but as the favourite topic of several romantic artists, most notably Johann Heinrich Füssli. The play had previously been illustrated several times, the last time by Charles Buchel in 1905.

Rackham used the same mixed approach he had adopted for the Grimm’s Fairy-Tales: his illustrations are both title pieces, full-page plates (both in colour and ink) and small pieces with strikingly decorative features. Some of the scenes he illustrated are completely inconsequential to the story narrated in the play (see, for instance, the choice of giving us a full-grown Leviathan only after the line “Ere the Leviathan can swim a league”). You have to appreciate the degree of freedom his publisher gave him: I’m not sure at all this would be allowed for a modern illustrator, regardless of his talent.

In 1909 Rackham will return on Shakespearian themes to illustrate the Tales from Shakespeare retold by Mary Lamb and her brother Charles. The collection includes retelling of The Tempest, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Winter’s Tale, Much Ado About Nothing, As You Like It, Two Gentlemen of Verona, The Merchant of Venice, Cymbeline, All’s Well That Ends Well, The Taming of the Shrew, The Comedy of Errors, Measure for Measure, Twelfth Night, Pericles Prince of Tyre (all done by Mary), and King Lear, Macbeth, Timon of Athens, Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, Prince of Denmark and Othello (narrated by Charles). On a side note, it’s funny how this work is often presented as done by Charles with “Mary’s help”. That’s quite a big fucking help.

Rackham will also do The Tempest, but it deserves its own section.

9. Undine (1909)

Probably my favourite work by Rackham was however done on a far lesser-known tale, Undine by Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué. The work is a literary fairy-tale drawing from several tropes, including the French folk-tale of Melusine, a water spirit who marries a knight and can stay with him on the condition that he will never see her on Saturdays (and when he does she resumes her mermaid shape). George MacDonald thought Undine “the most beautiful” of all fairy stories. It was adapted by E.T.A. Hoffmann into the homonymous opera (1816), by Pyotr Tchaikovsky as Undina (1869), by Antonín Dvořák in Rusalka (1901) where he incorporated the most sad and tragic elements of Hans Christian Andersen‘s Little Mermaid, and by Claude Debussy in a piano prelude from 1911. There are indeed similarities with Andersen’s mermaid, as our Undine marries the knight Huldebrand in order to gain a soul (something at which, spoiler alert, she tragically fails). A beautifully narrated version is here.

Rackham worked on an unabridged English translation of the story done by William Leonard Courtney and he did 15 colour plates and 41 inkworks, always for William Heinemann). Again, some of them are title pieces, or beautiful decorative figures arranged in strips and circles. The full plates are mostly in colour.

10. Richard Wagner (1910 – 1911)

Between 1910 and 1911, Rackham also produced illustrations for lots of works by Richard Wagner, specifically The Rhinegold, The Valkyrie, Siegfried and Twilight of the Gods, for a grand total of 66 colour plates and 16 inkworks. The powerful scenes in Wagner’s narrative are only enhanced by the incredible use of space Rackham does in his plates: figures blend in geometrical whirls, colours define factions and contrasting elements. Tragedy and war pervade the air.

Here’s some illustrations from the Rhinegold, the first music drama in which Wagner tells the tale of the three water maidens Woglinde, Wellgunde, and Floßhilde, and the trickster Alberich, the Nibelung dwarf.

Other characters include Wotan, ruler of the gods, and his wife Fricka, her sister Freia, the goddess of youth and beauty; Donner, god of thunder, and Froh, god of sunshine; the giants Fasolt and Fafner. You have a quite extensive collection of pictures here (though the math doesn’t match with mine).

11. Aesop’s Fables (1912)

So far, we have seen Rackham illustrating tales mostly involving humans and fairies or goblins (two things he represents with blurred lines) but we haven’t seen him working with animals. This edition of Aesop’s Fables will be the chance to show that he really kicks some serious asses also by drawing animals. He will do 13 colour plates and the incredible amount of 82 inkworks, and his style will resemble a lot some of the things he already did for some characters in Alice, but most of all is foreshadowing the chance he’ll have at the end of his career: the chance of illustrating The Wind in the Willows. For Aesop’s Fables, his animals are fully clothed and accessorized, with clothing style reflecting their personality.

12. Charles Perrault (1913)

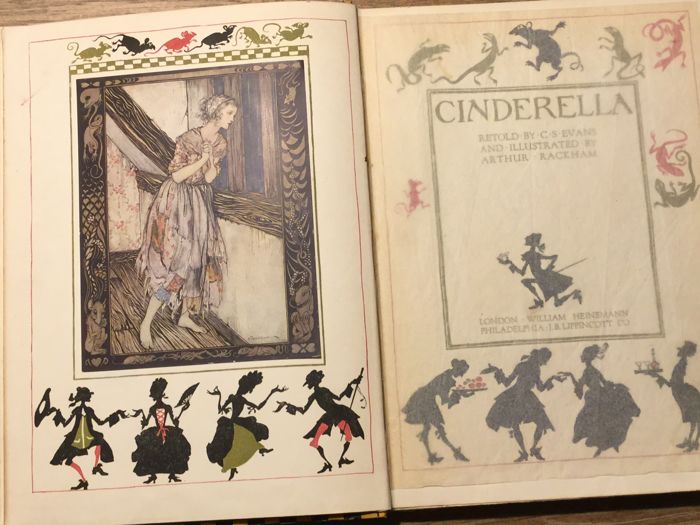

In 1913, Rackham’s illustrations for Mother Goose: The Old Nursery Rhymes, which had already appeared in the US monthly St. Nicholas Magazine, were collected into a publication. Charles Perrault’s fairy tale collection, originally titled Histoires ou contes du temps passé, avec des moralités or Contes de ma mère l’Oye, originally included “The Sleeping Beauty”, “Little Red Riding Hood”, “Bluebeard”, “The Master Cat, or Puss in Boots”, “Les Fées” (mostly known as “Diamonds and Toads”), “Cinderella”, “Riquet with the Tuft”, and “Hop o’ My Thumb”.

Rackham will come back to work on Perrault’s material several times: in 1919 he will do 1 colour plate and 60 silhouettes for a Cinderella edited Charles S. Evans. Already an innovator for his usage of ink, he will raise to new heights with these inked shadow theatre. Even for the coloured plates, his illustrations are framed with silhouettes, like dancing mice, and geometrical décor that are too often cut away in digital reproductions.

Some of his most original reinterpretations include the aspect of Cinderella’s fairy-godmother, with her witchy nose and hat, that give a sinister sound to her admonition of the consequences to face should Cinderella be late. There are lots of similarities between the style picked by Rackham and the style picked by Edmund Dulac for his own illustrations in 1929, although it’s very difficult to tell who influenced whom.

The following year, in 1920, he will do other 65 silhouettes, alongside 1 colour plate for The Sleeping Beauty edited by the same Charles S. Evans.

13. A Christmas Carol (1915)

A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens has been illustrated by charicaturist John Leech for its first edition, in 1843: the artist had been introduced to Dickens by his regular illustrator, George Cruikshank, who probably thought that ghost story needed a heavier hand. An additional edition, called A Christmas Carol in Four Staves, was conceived in 1855 for public reading, originally for charity and then, in 1858, for profit. An edition of this version had been illustrated, in 1868, by Sol Eytinge, an American illustrator who had also done works by Robert Browning, Washington Irving, and Edgar Allan Poe. His illustrations were mostly etchings and didn’t deviate much from what Leech had done. Other illustrated editions had been a New York one from 1902, with decorations by one Samuel Warner, and a London one from 1905, illustrated by the same Charles E. Brock who had done a terrific job on Sir Walter Scott‘s Ivanhoe for Service & Paton in 1897. Fred Barnard had then integrated John Leech’s work for a 1907 edition, with an introduction by Sir William P. Treloar, who was major of London at the time, and Arthur I. Keller had also tried his hand at it for a US edition published by David McKay in 1914 (luckily enough not incidentally inventing any abhorrent uniform for any abhorrent movement, this time). None of them will approach the work as Rackham did: as a proper ghost story.

14. King Arthur (1917)

Alfred W. Pollard was a scholar who edited Thomas Malory‘s tales around King Arthur and tried to undo the additional work done on it by William Caxton. The result was a publication called The Romance of King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table, for which Rackham did 23 plates, both colour and monotone, and 16 inkworks. His illustrations vary a lot from being very heavy with details and colour, to being plates with strokes of tones, to being almost abstract. One of the most famous and most innovative is “How at the Castle of Corbin a Maiden Bare in the Sangreal and Foretold the Achievements of Galahad”, which you can see here. My favourite is the questing beast (below).

15. Irish Fairy Tales (1920)

Among all the possible collections of Irish folk tales, Arthur Rackham got to illustrate this Irish Fairy Tales a retelling of ten tales by the novelist and poet James Stephens. These tales are:

- “The Story of Tuan mac Cairill”, a weird one in which Tuan, one of the original settlers of Ireland, tells the story of how he had been a stag, a boar, a hawk, and a salmon, eventually ending up roasted and eaten by the Queen of Ireland and being reborn as her son;

- “The Boyhood of Fionn”, in which two druids, Bovmall and Lia Luachra, raise a boy as their son: he’s eventually adopted by a robber and eventually defeats the fairy Aillen mac Midna;

- “The Birth of Bran”, where we are given our daily dose of cute puppies;

- “Oisin’s Mother”, probably my favourite, where two hunters refuse to attack a fawn and one of them ends up marrying a fairy woman and defeating an evil wizard;

- “The Wooing of Becfola”, another story that sets up during a hunt;

- “The Little Brawl at Allen”, where we see that Irish people are almost good as Scottish ones when it comes to drink too much and start a fight;

- “The Carl of the Drab Coat”, in which the son of the King of Thessal arrives in Ireland and challenges the Fianna to present a warrior who’s more powerful than him (spoiler: they send him back from whence he came);

- “The Enchanted Cave of Cesh Corran”, where we learn that the fairy king has four very ugly daughters;

- “Becuma of the White Skin”, where a fairy woman is banished to Ireland for having ran away from his husband and lots of stuff happens and eventually she becomes queen in a far-off country;

- “Mongan’s Frenzy” in which we meet Mongan, king of Ulster, and his misdeeds.

Rackham does 16 colour plates and 20 inkworks for the collection, and of course he focuses a lot on the weird and elementally confusing parts of these stories, as only him could do.

16. John Milton (1921)

In Greek mythology, Comus is the son of Bacchus, his cup-bearer and a demi-god of festivities, revels and night-feasts. Like Bacchus, it’s a guy who likes to party hard. A very popular character throughout the baroque period, like his father, featuring in operas like Les plaisirs de Versailles by Marc-Antoine Charpentier and King Arthur, by Henry Purcell and John Dryden. He’s also the central character in the novel The Unbearable Bassington by Saki but, most importantly, he’s at the centre of the homonymous 1634 masque by John Milton (full title: A Mask Presented at Ludlow Castle, 1634). The work was originally commissioned by a private patron, John Egerton, 1st Earl of Bridgewater, and it was published in anonymous form in 1637. Before you get excited it’s poetry alright but it’s nowhere near his Paradise Lost. The text was later used by the musician Thomas Arne in 1738, who did a masque in three acts.

From an editorial point of view, Milton’s Comus had already been illustrated once, by no other than William Blake, and there should be very little to add to that. You can see his illustrations here. Both guys were not well and they always got along perfectly.

Some painters had also represented scenes from the masque: in 1835, Francis Oliver Finch, one of the young artists in William Blake‘s group called The Ancients, takes the subject of the bacchanal in his The Dell of Comus; Edwin Henry Landseer painted a Defeat of Comus in 1843, in which he fully leveraged his ability in working with animals and hybrids; Charles Robert Leslie did this scene in 1844, with the demi-god trying to force an immobilized lady to drink from a cup.

Arthur Rackham is called to work on it by his editor and produces 22 colour plates, alongside 35 inkworks, and instead of presenting us scenes from the actual story he chooses to illustrate the misfortunes of the characters that are mentioned in the dialogue between Comus and the Lady he’s trying to corrupt. This is how we get the Hesperides, Echo, Naiades, Diana, a wonderful Daphne, un underwater Sabrina, water nymphs, and Iris, the goddess of the rainbow. Once upon a time, when I was a certified Disney Princess, I was crazy about this illustration and it determined my nickname as a child.

17. The Tempest (1926)

As I was saying, after working on Midsummer Night’s Dream in 1908 at the beginning of his career, Rackham comes back to work on a structured Shakespearian subject almost twenty years later. With its evil witches, and wizards, and monsters, and magic, and weird stuff, The Tempest is probably the second most suitable subject for Rackham, although I would have loved to see him working on MacBeth. For The Tempest, he works equally in colour and inkwork, producing 20 illustrations of each. Less experimental than others, it’s probably his most mature work.

18. The King of the Golden River (1932)

The King of the Golden River (complete title The King of the Golden River or The Black Brothers: A Legend of Stiria) is a literary fairy-tales written in 1841 by John Ruskin for Euphemia Gray, a girl who was 12 years old at the time and whom Ruskin later married (it’s a little less sordid than that: Ruskin was 21, when Effie was 12, and waited until she was 19 to marry her: regardless of that, the marriage was annulled on the ground of never having been consummated, so their relationship is generally considered to have been platonic). It’s a story featuring a personified Southwest Wind, and two brothers provoking his/her/their anger. The original edition featured illustrations by Richard Doyle, uncle of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and co-illustrator of Charles Dickens‘ Christmas books (which do not include A Christmas Carol, confusingly enough).

Rackham takes up Doyle’s work and integrates it with an additional 4 colour plates and 13 inkworks. I have none of the inkworks, but I can give you one of the colour plates.

19. Hans Christian Andersen (1932)

You might be thinking “again?”, but in fact this is the first time Rackham gets to illustrate Hans Christian Andersen‘s Fairy Tales: he has done pretty much everything around fairy-tales, this is the last one, and he does so with 12 colour plates, 43 inkworks and 9 silhouettes in the fashion of what he already did for Charles Perrault‘s Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty. His usage of silhouettes is often supporting the narration, as it happens for instance for “The Emperor’s New Clothes”, in which the artist uses silhouettes to portray the naked monarch (or, most appropriately, to avoid portraying him) and rather chooses to focus his colour plate on the child pointing her finger.

He abandons such devices when they’re not appropriate for the tone or style of the tale. For instance, in “The Little Match Girl” Rackham chooses to represent the Christmas tree scene with strokes of colour that convey both the light, the warmth and the hallucination aspects of the situation, in a style that’s more similar to the one he had used for Wagner.

20. Goblin Market (1933)

Goblin Market is a narrative poem by Christina Rossetti, the sister and model of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, herself an accomplished poet and beloved author for children. It tells the story of Laura and Lizzie, two sisters, and the temptation they face in a goblin market, where a merchant tries to trick them into eating a twilight fruit. The way Rossetti describes these river goblins, with animal faces and tails, is very much aligned with Arthur Rackham’s imagination, but unfortunately his work on the subject only gave us 4 colour plates, alongside 19 inkworks. Previous illustrations had been provided by Laurence Housman (1893).

21. Edgar Allan Poe (1935)

There’s little doubt that Edgar Allan Poe is one of the most important and influential authors, like ever. Whoever tries to deny that, is a condescending asshole who still advocates the division between literature and a so-called genre literature (and that’s why you’re having all those nightmares, honey). He wrote a lot, like really a lot, and though lots of his best known works are considered to be Gothic literature, he also worked around something that might be considered more adherent to the realm of the fantastic (though profoundly disliking certain tropes pulling towards the theory of transcendentalism).

Mostly a writer of poems and short stories, he published a lot of collections during his lifetime and his first published work was indeed a collection: Tamerlane and Other Poems, in 1827. However, the only collection of “tales” he published was Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque in 1839, which included, among others, “The Fall of the House of Usher“. Tales of Mystery & Imagination was a posthumous collection, which included “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” and “A Descent into the Maelström” (both written after the publication of the Grotesque and Arabesque tales). It was printed by Grant Richard, London, in 1902, and then taken up again by Padraic Colum in 1908, when poems, comedies and essays were excluded from the collection, alongside two long stories (The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket and “The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall“). In 1919 London’s George G. Harrap and Co. published what I believe was the first illustrated edition, with black and white plates by Harry Clarke, and the same edition was expanded in 1923, with the addition of eight colour plates by the same author. You might remember Harry Clarke as one of the most important Irish members of the Arts and Crafts Movement, and because he also did illustrations to The Fairy Tales of Charles Perrault in 1922. Arthur Rackham’s edition, for which he did 12 colour plates and 28 inkworks, seems to be the third illustrated edition, at least this part of the Atlantic.

The collection includes twelve of the most famous stories by Poe:

- “William Wilson“;

- “The Gold Bug“;

- “The Fall of the House of Usher“;

- “The Masque of the Red Death“;

- “The Cask of Amontillado“;

- “A Descent into the Maelström“;

- “The Pit and the Pendulum“;

- “The Purloined Letter“;

- “Metzengerstein“;

- “The Murders in the Rue Morgue“;

- “The Tell-Tale Heart“;

- “The Black Cat“.

Rackham’s illustration swing from the surrealist and impressionistic (such as his work for the Masque of the Red Death) to the vibrant symbolists touch he had used for Wagner, such as this plate for “Metzengerstein: A Tale in Imitation of the German”, Poe’s first short story to be published, in which we follow the adventures of young Frederick, the last of the Metzengerstein family, and his feud with the Berlifitzing family.

22. Peer Gynt (1936)

Peer Gynt is a Norwegian five-act play in verse, written in Danish by Henrik Ibsen and firstly published in 1867. Deeply inspired by Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe’s collection of Norwegian fairy tales (which you know everything about, by now), it tells the story of this guy and his epic journey from the Norwegian mountains to the North African desert. In his journeys, he meets trolls, witches, Bedouins and the Sphinx. It was considered bad, like really bad. It was put to music by Edvard Grieg, at Ibsen’s request, and some parts of this suite are really popular.

Arthur Rackham worked on 12 colour plates and 38 inkworks.

Other works and legacy

1900 – 1910

These are far from being the only works Arthur Rackham worked on: in the recent volume The Art of Arthur Rackham: Celebrating 150 Years of the Great British Artist you can find coloured and black and white plates coming also from Eleanor Gates‘ play Good-night (Buenas Noches), published in 1907, and from Gulliver’s Travels of 1909. As I said, I’m not really a fan of Jonathan Swift‘s masterpiece, as I’m not a fan of metaphoric and allegoric works (and if you only know the Lilliput part I understand you have no idea what I’m going on about). There’s also three plates illustrating Adventures in Wizard-land – The Rainbow Book Tales of Fun & Fancy by Mabel Henriette Spielmann, published in 1909: “The Fish-King and the Dog-Fish”, in colour; “What a glorious ride that was!”, in black and white; “Taking the boy and girl by a hand, he led them”, also in black and white. Rackham was only one of the illustrators, alongside the Irish illustrator Hugh Thomson (who had done pen-and-ink illustrations for Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, and J. M. Barrie), Bernard Partridge (nephew of the official portrait painter for Queen Victoria, if that’s a merit of some kind), Lewis Baumer (a charicaturist mostly known for his work on the magazine Punch), Harry Rountree (whom we have already mentioned as one of the illustrators for Alice in Wonderland) and C. Wilhelm (pencil name of William John Charles Pitcher, an English artist, costume and scenery designer who worked on lots of ballets and pantomimes including A Midsummer Night’s Dream for Robert Courtneidge in Manchester).

1910 – 1920

In the same centennial selection, you can also find plates for The Allies’ Fairy Book, a collection of stories with an introduction by Edmund Gosse published in 1916 which we know included at least “What Came of Picking Flowers“, “Lludd and Llefelys“, “The Nine Peahens and the Golden Apples” (for which Rackham did what probably is the most beautiful dragon with damsel ever), and “The Battle of the Birds“. Other illustrations for fairy-tales are included in the collection English Fairy Tales, published in 1918 by the Australian folklorist Joseph Jacobs, and in the volume Some British Ballads of the same year (which we know also included “Lord Randall” and “The Three Ravens“). There is also one illustration each for The Springtide of Life: Poems of Childhood by Algernon Charles Swinburne, for which he did 8 plates, and for Snickerty Nick, a drama by Julia Ellsworth Shaw Ford (no idea what’s that about, but there’s a weird-ass tree Tolkien would have liked).

The (roaring) 1920s

From the 1920s, aside from the Irish Fairy Tales and the reprise on works on Perrault’s material, we also have the only three coloured plates from the play A Dish of Apples, by Eden Phillpotts: there’s a Pomona with two impish assistants, children playing under a tree approaching winter and harvesting the last apples, and a fairy queen of some kind, one more beautiful than the other. The complete edition, with illustrations, is available here. Below you have the second plate, probably my favourite, but the inkwork is also of stunning beauty.

From the early 20s, it’s also worth mentioning the satirical novel Where the Blue Begins, by Christopher Morley, published in 1922 and illustrated the same year in a caricatural style, and A Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys, by Nathaniel Hawthorne, which I have already talked about in relation with The Wind in The Willows. A Wonder Book retells Greek myths, specifically:

- “The Gorgon’s Head”, covering the story of Perseus killing Medusa;

- “The Golden Touch”, about King Midas;

- “The Paradise of Children”, recounting the story of Pandora opening the box (one of Rackham’s most beautiful illustrations ever);

- “The Three Golden Apples”, with Heracles and his journey to the Hesperides’ orchard;

- “The Miraculous Pitcher”, telling the story of Baucis and Philemon who provide food and shelter to two strangers only to find out that they are Zeus and Hermes in disguise;

- “The Chimæra”, presenting us Bellerophon who tames Pegasus and kills the Chimæra.

The book was firstly published in 1851 and Walter Crane had illustrated a 1893. Rackham worked on it in 1922.

In 1925 Rackham also did illustrations for the first edition of Margery Williams‘ Poor Cecco: The Wonderful Story of a Wonderful Wooden Dog Who Was the Jolliest Toy in the House Until He Went Out to Explore the World, a precursor of children’s book featuring toys as main characters. Rackham again uses colours to highlight the different worlds, the one of adults and men, and the one of children, toys and animals, as you can see from the plate below.

The 1930s

Aside from The King of the Golden River and Goblin Market, which I talked about, other works worth mentioning are A Visit from St. Nicholas, also known as The Night Before Christmas, one of the works that defined our idea of Santa Clause, which Rackham illustrated in 1931 after Jessie Willcox Smith had done an edition in 1912. Arthur Rackham gives us a dwarvish, almost impish Saint Nick, and that’s the charm about it.

In 1931, Rackham also does some naturalistic work for The Compleat Angler, a book by Izaak Walton which was firstly published in 1653 and it’s a celebration of the art of fishing and the riverside atmospheres, but also includes elements of resistance to the Puritan regime of the 1650s. The otter I gave you for the title of the post for Chapter 7 of The Wind in the Willows is in fact one of Rackham’s illustrations from this book.

It’s also worth mentioning his own collection, called The Arthur Rackham Fairy Book, published in 1933 and for which he created the chance of working on stories and atmospheres he hadn’t tried his hand on: you have orientalist work for “The Story of Aladdin” and “The Story of Sinbad the Sailor”, for instance, and the “Hop o’ My Thumb” illustration I already quoted when I talked about Soria Moria Castle and the protagonist’s similarities with the character of Tom Thumb.

Note: a far better work than mine is done here.

Influences on Disney

Walt Disney admired Arthur Rackham’s watercolour and pen & ink style, and, while endeavouring to work on their first big project Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, he instructed Gustaf Tenggren to work with Claude Coates and Sam Armstrong to adapt it for the usage in the animation. Tenggren was an illustrator of Swedish origins and, at the time, the profound influence of Arthur Rackham on his works was already obvious, probably one of the reasons he was hired by Disney in 1936.

Rackham is often quoted as an influence by many important members of the studios, such as Mel Shaw, who is said to have looked at Rackham for some sequences of the Musicana project, and Martin Provensen in this 1983 interview:

When I was older, a group of books that meant a lot to me—and I still admire them—were the animal stories illustrated by Charles Livingston Bull. He drew animals very realistically, brilliantly, with a great deal of knowledge and skill. I think he worked in the late twenties and early thirties. When I was slightly older, I discovered Rackham and Dulac. And there was Kay Nielsen, who illustrated Danish fairy tales, and whom I got to know at the Disney studio many years later. He was a great illustrator. All these books were very important to me. (Nancy Willard, “The Birds and the Beasts Were There: An Interview with Martin Provensen,”).

If you’re familiar with Snow White’s nightmare sequence, in the forest, right there you might see the most striking similarities with Rackham’s mischievous and nightmarish trees. Disney was no stranger to moving trees, as we can clearly see in earlier works such as the Silly Symphony Flowers and Trees (1932) in which I do believe we see our first animated evil tree. This is something that might require a post in itself: for now, I can only suggest you read this very accurate post on Snow White’s horror features There are also some interesting insights here.

Influences on Tolkien

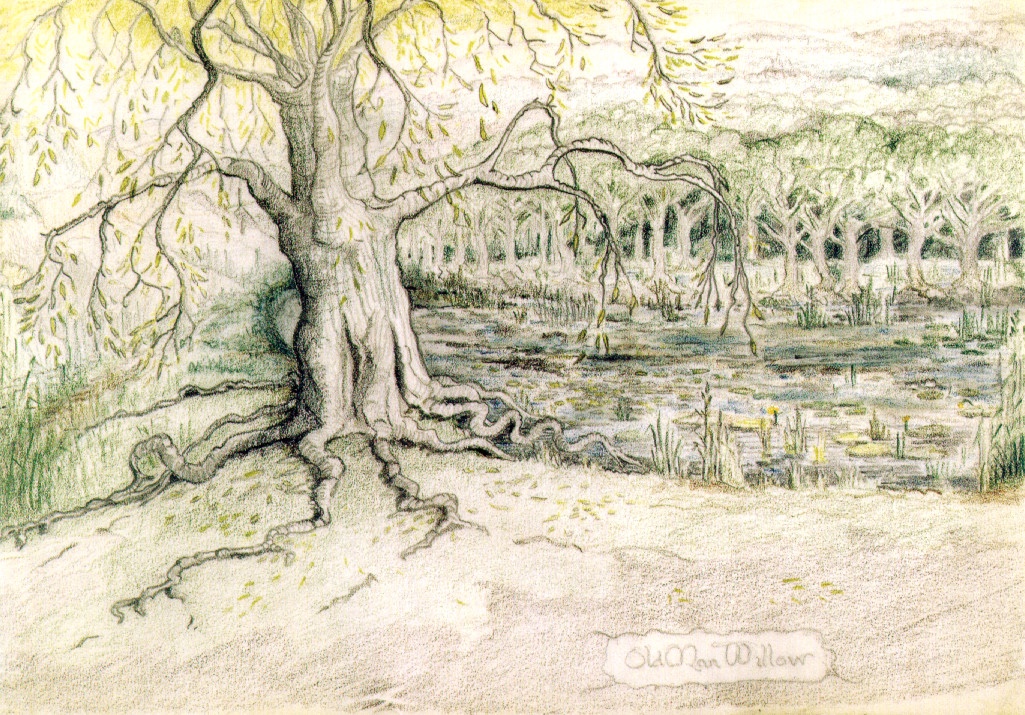

Rackham’s trees are also a point of conjunction with my favourite Oxford Professor.

According to Humphrey Carpenter in his Biography, Tolkien knew Arthur Rackham very well and openly admitted that the idea of Old Man Willow shutting someone up in a crack probably came from «gnarled trees» as drawn by him. It’s a theme we have both in The Adventures of Tom Bombadil and in The Lord of the Rings, where the same character helps our four hobbits to escape the willow’s grip. You can find some notes on it by Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull in both their Lord of the Rings Reader’s companion and their annotated edition of The Adventures of Tom Bombadil.

Up woke Willow-man, began upon his singing,

sang Tom fast asleep under branches swinging;

in a crack caught him tight: snick! it closed together,

trapped Tom Bombadil, coat and hat and feather.

In her essay “How Trees Behave — or do they?”, included in the relatively recent collection There Would Always be a Fairy-Tale, Tolkien scholar Verlyn Flieger also picks up on the influence of Arthur Rackham on Tolkien’s trees, and she defines him «the premier illustrator of Tolkien’s boyhood». The connection here is made on the Huorns, the moving trees of Fangorn Forest which will wage war on Isengard at Treebeard‘s calling. According to Flieger, «Their “tangled boughs,” “hoary heads,” and “twisted roots” seem straight out of an Arthur Rackham illustration». Another possible point of connection, though both well-documented and more than far-stretched, is lined up on this blog and concerns Rackham as a possible source of inspiration for Goldberry. Both water-nymphs and evil-faced trees are something interesting that I might decide to explore in a separate post.

3 Comments

Sea

Posted at 08:49h, 25 Januarygreat post, very detailed and interesting. thank you so much

Pingback:The Leech of Folkestone (one of the Ingoldsby Legends) – Shelidon

Posted at 00:14h, 31 January[…] work, I feel I should dedicate some attention to him as well. I poured some works he illustrated in this post, but some of the stuff deserves more […]

Pingback:High Waters at Catfish Bend (a Mardi Gras story) – Shelidon

Posted at 00:02h, 16 February[…] from the name comes from John Milton‘s Comus (a guy we have already encountered while talking about Arthur Rackham‘s illustrations to the masque); the second oldest one was the Knights of Momus, established […]