People are always misplacing this one and, due to the proximity of his exhibition to the Goya one I wrote about yesterday, I’m unsurprised that some people queuing for the ticket thought they were contemporaries. Domḗnikos Theotokópoulos, known as El Greco because he moved to Spain, was born in October 1541. Goya was born in March fucking 1746. They have two hundred years of difference. Still, can you blame the laymen when this is what you see?

Anyway, let’s proceed with order.

1. The Exhibition

Still in Milan, this one is on the main floor of the royal palace, and it’s curated by a joint venture of Juan Antonio García Castro, director of the museum in Toledo, Palma Martínez – Burgos García, professor of history of art in La Mancha and author of one of the most modern essays on the painter, and Thomas Clement Salomon, bright young author and journalist. None of them is 84 years old and one of them is a woman, which I think is a good start.

The itinerary is divided into sections, from the original work influenced by traditional Orthodox art to religious subjects, and its main focus is always to keep his work grounded in his inspirations and influences, often by casually putting a Tiziano on the wall so that people can see the difference by themselves. It’s ambitious to say the least, and the lighting is absolutely lavishing.

It’s also the first time Italy is seeing stuff such as the Martyrdom of San Sebastiano, coming from the Cathedral of Palencia, the Expulsion of the Merchants from the Temple coming from the Church of San Ginés in Madrid, and the Coronation of the Virgin painted for the high altarpiece of the Santuario de Nuestra Señora de la Caridad in Illescas, Toledo.

It would be improper for me to say which paintings I liked best, so this time I think I’ll just give you a couple of themes and elements that particularly hit my imagination.

1. Hands

I won’t be the first to say it, but you have to take a look at how this guy painted hands. Particularly the hands of men, and particularly the hands of suffering men such as Jesus and Saint Francis. They’re thin, bony hands, with nails made shiny but the incredible light washing them, and their pose is simply perfect. If you’re an artist who needs to get better at hands (and who doesn’t), go and sketch El Greco’s hands.

2. Backgrounds and Foregrounds

2. Backgrounds and Foregrounds

This is why I don’t blame people who think this guy lived in the late XVIII Century. Not only the figures are much closer to Gauguin than Tiziano: take a close look at these paintbrushes, at how a thin black like achieves a natural staccato between the flesh and the robes, and then try to convince me that this thing is from 1610.

3. Everywhere Toledo

You might not like it, and personally I’m not sure how I feel about it, but one of the revolutionary and controversial moves El Greco did in his paintings was to set them in contemporary times and places. He claimed it was for people to feel closer to the scene, and the argument worked even with the Catholic Church, so who am I to argue? One bonus side is that we get to see a lot of his beloved Toledo as the background of religious subjects who have nothing to do with the city.

My personal favourite is represented behind a portrait of Saint Martin, the famous Roman knight who cut his mantle in two pieces to give half of it to a beggar during a cold winter night. It’s a city made of light and water, bare reflections and optic tricks, and the chill they bring you is not a physical one, but it’s pure emotion.

4. Laocoön

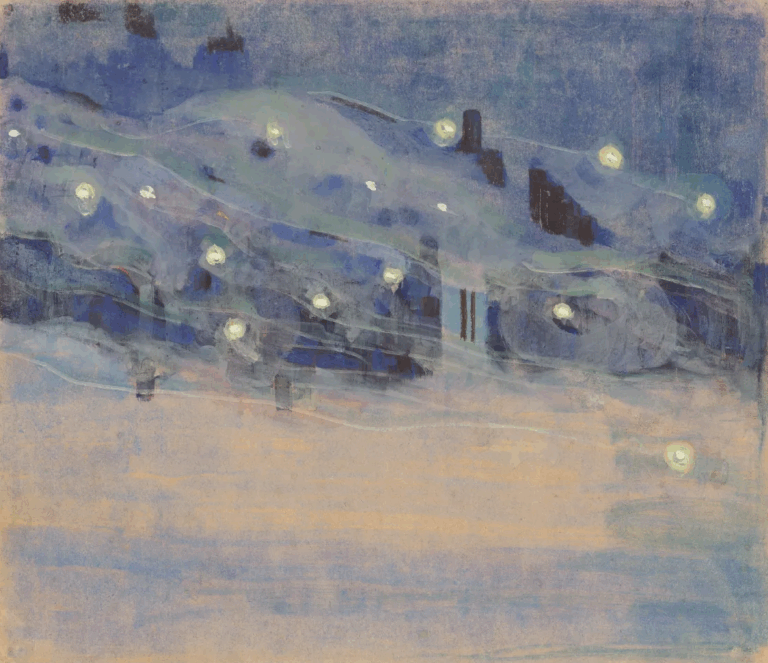

I know, I said I wasn’t going to pick a favourite painting, but come on, that thing is gorgeous! It’s the painting I showed you at the beginning of the article, created between 1610 and 1614 during four of the most prolific years in the artist’s entire career, and it’s probably my favourite because I have a natural dislike for most religious subjects.

The subject is mythological of course: as you might remember, Laocoön was a Trojan priest and one of the few people still in possession of a brain after seeing the Greeks seemingly leaving their shores. He tried to warn the people of Troy not to bring the fateful wooden horse inside the city’s walls and his god Poseidon rewarded him by sending a sea monster to swallow him and his two sons, Antiphantes and Thymbraeus. One can survive a ten-year siege but, apparently, not Poseidon’s whims.

The classical Laocoön Group had been unearthed in February 1506 in Rome, in the vineyards of one Felice De Fredis who immediately warned Pope Julius II. Luckily enough, the Pope was an enthusiastic scholar and was very fond of classical arts: he was the patron of both Michelangelo and Raphael, commissioned the Sistine Chapel ceiling, the expansion of the Vatican and Bramante’s courtyard. He was also a warmonger and was mostly responsible for the tensions with the future Protestant Church. Still, another guy might have disregarded the discovery or even destroyed it.

Julius II sent to the site his best people, including Michelangelo and the Florentine architect Giuliano da Sangallo, accompanied by his eleven-year-old son Francesco who would later become a sculptor.

The discovery had a tremendous impact on intellectuals and artists way into the Baroque period. To better put in context El Greco’s groundbreaking work, the exhibition in Milan dedicates a whole room to the painting and gives us a 1:1 chalk reproduction of the original classical complex on one side.

On the other side, we are shown enlarged panels with some contemporary sketches of the work, specifically:

- Sisto Baldocchio‘s etching included in the XVI Century Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae;

- Marco Dente‘s drawing from 1523;

- Nicolas Beatrizet‘s engraving from the French artist, also included in Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae;

- a parody by Tiziano.

This last one has to be my favourite, and you can almost see how the guy was so fed and tired of hearing people talking about the bloody statue.

2 Comments

Pingback:Two things to see in Ghent – Shelidon

Posted at 17:14h, 07 December[…] The two central paintings in grisaille, giving the illusion of painted statues, are John the Baptist, again represented as a bearded old man, and St John the Evangelist holding the traditional cup with a little dragon taking a bath in it. You might remember we saw something similar painted by El Greco. […]

Pingback:White Gold: three centuries of Ginori porcelaine – Shelidon

Posted at 14:05h, 12 December[…] both in bronze and porcelain. As you might remember from the room dedicated to the subject in the recent exhibition dedicated to El Greco, the discovery of this statue had a tremendous impact on the imagination of the contemporaries, and […]