Goya in Milan

The exhibition is called “The Rebellion of Reason”, echoing Goya’s famous statement on the monsters-producing sleep of reason, it’s set up at the lower level of Milan’s Royal Palace, and it’s curated by Víctor Nieto Alcaide, an 83-years-old Spanish historian of arts (and historian of Spanish art) who published a beautiful book on the usage […]

The exhibition is called “The Rebellion of Reason”, echoing Goya’s famous statement on the monsters-producing sleep of reason, it’s set up at the lower level of Milan’s Royal Palace, and it’s curated by Víctor Nieto Alcaide, an 83-years-old Spanish historian of arts (and historian of Spanish art) who published a beautiful book on the usage of light in the Renaissance and the Middle Ages. It spans across 7 sections and doesn’t display an extensive collection, translations are questionable, texts in the curated boards are hilariously banal, but it’s a unique chance to see incredible pieces and you shouldn’t miss that.

To encourage you for a visit, or to make up if you’re unable to drop by and see it, here’s my top 5 works you can see in the exhibition.

5. Might not the pupil know more?

Caprice number 37, etched between 1797 and 1799, this work opens the section dedicated to dunces, through which Goya denounces the educational system. You can see why it’s close to my heart. Goya points the finger against teachers, in this particular stance, and those teachers who work through the forceful imposition of authority, threatening a pupil instead of doing their fucking job. You can read more about it on the Prado website and on the MET website.

The etching is displayed with the original copper plate, part of a massive restoration endeavour.

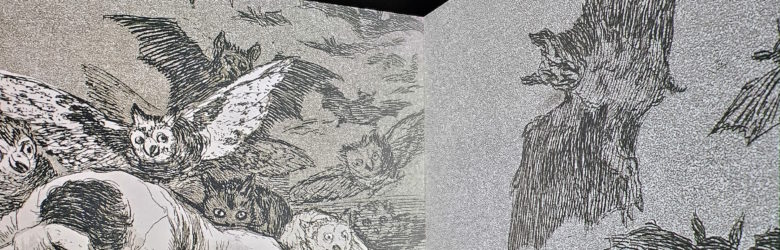

4. The Sleep of Reason

You know I’m not snobbish, and I won’t say something is not good just because everybody likes it. Except for Everything Everywhere All At Once, of course: I’m still shunning that.

It was very emotionally impactful to see the copper plate for this masterpiece: the fine details are amazing.

3. Scenes from an Asylum

Casa de Locos (literally: Madhouse) is a very small oil on panel painted between 1812 and 1819 after he went to the Saragozza mental asylum to visit his aunt and uncle who were inmates over there. Goya had recently been ill himself, a sickness that created a lasting hearing impediment, and had to battle depression in a period where mentally ill people were seen as possessed.

The dimensions of the painting do nothing to impair details: the claustrophobic scene is illuminated just by the light filtering through a barred window up on the barren wall, characters are raving in a state of complete neglect and they sport accessories meant to symbolise the madness of institutions.

2. Cone-hooded people

I’m cheating a bit here, grouping two paintings into one category, but they’re rightfully placed together. The first one is the Procession of Flagellants, painted between 1808 and 1812 and depicting a tradition technically outlawed by King Carlos III back in 1777.

The repentant zealots are dragging a crucifixion and a statue of Nuestra Señora dela Soledad, cleverly depicted without a face. The white fabric on the flagellants is half-transparent, a thing you can’t quite appreciate from any picture, and the largest brush stroke has to be 1 cm maximum. The whole thing is so vivid that it looks much, much smaller.

The second painting is The Inquisition Tribunal, done between 1812 and 1819, and features a miserable dude being interrogated on the stand while two other miserable dudes are sitting miserably on the side. Just like the previous painting, it’s an accusation of how Ferdinand VII’s policies are dragging back Spain to obscurantism.

Guests and witnesses are no more than strokes of the brush, as are the devils and flames on the sanbenitos (robes) of the accused. This unfortunately means they had been found guilty and they were going to burn in the public square.

I think it was a stroke of genius to place these two paintings together with a quote summoning Goya in front of the Inquisition itself because of the Maja Desnuda. Don’t get your hopes up: they’re not on display.

1. The Colossus

The most impressive piece on display, without any doubt, especially after the whole misattribution shenanigans. It isn’t big either, 116 x 105 cm, and again the details of the landscape below the giant are absolutely impressive. Still, there is no way to see what the giant is crushing between his fists nor, I’m afraid, you can get a better look at his ass.

So, that’s it. My top 5. Did you see the exhibition? What did you think of it?

Next up on my list are El Greco, also at the Royal Palace, Van Gogh at the Cultures Museum, and the exhibition on Samurai Women at Tenoha, with the illustrations of Benjamin Lacombe. I should really get a move on, with this last one.

One Comment