A few weeks ago, I talked about Arthur Rackham, one of my favourite illustrators, and his works. One of his works was illustrations for an obscure collection of weird tales, called The Ingoldsby Legends, and they caught your attention. I already brought you one of the tales: today, I bring you another: “The Lay of St. Cuthbert”.

The cover and some content of an edition currently available here.

1. What’s a Lay, precious?

Some of the Ingoldsby Legends are called “lays”: “A Lay of St. Dunstan“, “A Lay of St. Gengulphus“, “The Lay of St. Odille“, “A Lay of St. Nicholas“, in the first series; “The Lay of St. Aloys“, and “The Lay of the Old Woman Clothed in Grey” in the second series. “The Lay of St. Cuthbert” is the third one in the second series. But what is a Lay and in which sense it’s used by Thomas Ingoldsby of Tappington Manor, the pen name behind which it’s hidden our Richard Harris Barham, witty clergyman from Canterbury?

A Lay in the broader sense is a short ballad or a lyrical poem. The term probably comes from the Old High German and Old Middle German leich, meaning play or song. Hence, we’re talking about something in verse with a highly musical twist. There are also specific kinds of lays: the medieval French lay (also called lai) is usually in octosyllabic couplets and deals with adventure and romance, and was usually composed between France and Germany in the XIII and XIV Century; the Breton lay, on the other hand, is a narrative piece of romance with a supernatural twist (the earlies examples of this genre are from the XII Century: there’s old French lays such as The Lais of Marie de France and Middle-English lays such as “Sir Orfeo” and “The Franklin’s Tale” from the Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer); the Germanic lay, a form of epic poetry from the Early Middle Ages (examples are the Hildebrandslied in Old High German, the Finnesburg Fragment in Old English, works like the Hamðismál or “The Lay of Hárbard”, in Old Norse).

Some of the most significant lays in literature are:

- “The Lay of the Nibelungs” (Nibelungenlied), an epic poem in Middle High German written in the XI Century and based on an oral tradition dating back to the V and VI Century, which basically the German counterpart of the Old Norse lays made famous by Richard Wagner;

- “The Lay of Hyndla” (Hyndluljóð), an Old Norse poem which is generally considered a part of the Poetic Edda, which tells the story of the seer Hyndla and her ride towards the Valhalla with the goddess Freyja (respectively riding on a wolf and on Hildisvíni the boar) and for which there are beautiful illustrations by W.G. Collingwood;

- “The Lay of Grímnir” (Grímnismál), another Old Norse poem part of the Poetic Edda, in which we find our old friend Grímnir in a little bit of a fix, and is eventually able to have vengeance against King Geirröth;

- “The Lay of Vafþrúðnir” (Vafþrúðnismál), the third Old Norse poem from the Poetic Edda, a conversation between Odin, Frigg, and the giant Vafþrúðnir (one of the main sources for the Prose Edda by Snorri Sturluson): there are some beautiful illustrations by Lorenz Frølich;

- “The Lay of Svipdagr” (Svipdagsmál) consisting of two lays, “The Lay of Fjölsvinn” (Fjölsvinnsmál) and The Spell of Gróa.

The “lay” format was later revived in the romantic period, and we also have relatively modern examples such as The Lay of the Last Minstrel published by Walter Scott in 1805. Tolkien also tried his hand at it for telling the tale of Beren and Lúthien for instance: he never published them, but his son Christopher had to eat and collected them in a volume called The Lays of Beleriand, containing The Lay of the Children of Húrin and The Lay of Leithian. A little less-known but far more legit is his The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun, a Breton lai based on “An Aotrou Nann hag ar Gorigann” (Lord Nann and the Fairy) and which was willingly published in Welsh Review in 1945.

A scene from “The Lay of Vafþrúðnir” by Lorenz Frølich: Odin and the giant Vafþrúðnir are discussing who’s going to win the Superbowl this year.

2. St. Cuthbert: who’s this guy?

Saint Cuthbert (allegedly born around 634 in Dunbar, Northumbria) is a monk, bishop and hermit of the Celtic tradition, one of the most important medieval saint of Northern England.

The context in which our saint is born is one of recent conversion: King Edwin had only recently been converted to Christianity and baptised by Paulinus of York from the Gregorian/Augustiniane mission, but this was far from peaceful: as it often happened during this tumultuous period of the island’s history, clashes between the new faith and pagan rules were frequent and monks like Paulinus are one of the reasons we have such little examples of folklore from that time. King Edwin fell at the Battle of Hatfield Chase one shy year before our Cuthbert was born, and was been venerated as a saint. His successor King Oswald, son of Æthelfrith of Bernicia, returned from exile and ascended to the throne precisely in 634, and increased the conversion processes started by his predecessor through calling more monks to swarm his lands: among his acts, he called Irish monks from the small island of Iona, in the Inner Hebrides, to work with the Gregorians to build monasteries such as the one at Lindisfarne, where Cuthbert spent much of his career as a monk. There was a lot of hostility between the Celtic tradition and the Roman one, something it wouldn’t be an understatement to call a civil war: on one hand we had Wilfrid, Bishop of Northumbria and supported of the Roman ways, and on the other hand we had Ceadda, appointed for the same role. Cuthbert was a follower of the Celtic tradition, but was mentored by Eata of Lindisfarne, Bishop of Hexham (678 – 681) and Lindisfarne (681 – 685), and conformed easily to the adoption of the Roman ryte after the Synod of Whitby, which decreed it in 664. He is often portrayed as a pious, obedient and meek guy, although he’s also the guy who pretended to have had a mystic vision in order to have his own cousin crowned king (Aldfrith of Northumbria).

From a literary point of view, the main source is Historia de Sancto Cuthberto by Bede the Venerable, an account of events, grants of properties, subsequent losses, miracles and such. Not the most exciting of sources. An older source is Vita Sancti Cuthberti, in prose, compiled between 698 and 705. A later source is The Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs and Other Principal Saints by Alban Butler.

On the territory, Cuthbert left his mark mostly in the monasteries of Melrose and Lindisfarne, in which he spent most of his life, and around his tomb in Durham Cathedral, where his body was supposedly discovered to be intact years after his burial. All of them are beautiful places, nowadays: St Mary’s Abbey in Melrose is a ruined Gothic abbey in Roxburghshire, described by Sir Walter Scott precisely in his “The Lay of the Last Minstrel”, which I already mentioned while talking about lays, and painted by J.M.W. Turner in some beautiful watercolours around 1822. Some of his sketches are preserved at the Tate Gallery and visible here.

Lindisfarne on the other hand is a tidal island also known as “the Holy Island of Lindisfarne”, or simply “the Holy Island”: it features a priory, founded around 634 by Irish monk Saint Aidan who came from Iona at the request of King Oswald, and a castle built when such priory was destroyed by the Vikings and rebuilt by the Normans. The island also has two lighthouses, one of which in the form of a pyramid because of reasons. For the ruins of the priory, there’s a beautiful watercolour by Thomas Girtin.

The Cathedral Church of Christ, Blessed Mary the Virgin and St Cuthbert of Durham, also known as Durham Cathedral to preserve people’s sanity and life-span when mentioning it, is a Norman Era church built around 1090 and declared UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1986.

The relics of our Cuthbert arrive at Durham only after a few misfortunes: in 875, monks were fleeing the Island of Lindisfarne with Vikings at their heels, and carried the relics with them, but they remained itinerant until 882, when they eventually settled at at Chester-le-Street, few miles north from Durham.

The town didn’t exist, back then, and Symeon of Durham, in his XII Century chronicle Libellus de exordio atque procurso istius, hoc est Dunhelmensis, tells us the story of how it came to be. The monks, who were roaming around with the coffin of their saint on their backs, found themselves within a loop of the River Wear. Finding themselves in such a charming place, the monks would have us believe that the coffin they were carrying miraculously stopped moving at the foot of the hill of Warden Law. Their leader Aldhun decreed a fast of three days (which basically is to say that he left them without food in the vain hope of convincing them to resume their wandering). During the fast, St Cuthbert himself appeared to one of the monks, a guy named Eadmer (and no shit: have you ever tried to stay three days without food?) and gave instructions that his coffin had to be taken to a place called Dun Holm. Trouble was, Bishop Aldhun had no idea where this Dun Holm was (and Eadmer had to be a really fun fellow to be around). Enters a couple of milkmaids, who are searching for a dun cow. This cow thing is apparently a trope in English folklore: someone looses a dun cow (dun being a colour) and stuff happens when people look for it. This time, the monks follow the milkmaid and they settle where the cow is found, thus building what a first “shelter” for the relics. In 998 this shelter became a stone building called the White Church, and in 1093 the current structure was born.

The Shrine of Saint Cuthbert was positioned within the apse and was allegedly beautiful.

…it was estimated to be one of the most sumptuous in all England, so great were the offerings and jewells bestowed upon it, and endless the miracles that were wrought at it, even in these last days.

— Rites of Durham

Since I’m talking in hypothetic form, you might have guessed how this thing ends: in 1538, when King Henry VIII was being paranoid about a possible invasion from Germany and France and thus dissolved the monastic orders in order to gain their riches, the shrine was destroyed, the body was exhumed to strip it of any gold and, according to the Rites of Durham, was discovered to be uncorrupted, the defining miracle of Cuthbert.

J.M.W. Turner, Durham Cathedral, on display at the Royal Academy

Another important landmark is in Bellingham, Northumberland, where you can find a place called Cuddy’s Well. It’s a “holy well”, next to a church dedicated to Cuthbert, where Reginald of Durham records the happening of three miracles:

- the daughter of a poor bridge-builder is sewing a dress on the feast day of St Lawrence and her hands becomes paralyzed, clutched around the dress, but she is cured after drinking water from the well;

- the same girl is about to get married but her father’s cow is seized as requisition for a failed payment, and the saint strikes the landlord’s house with lightning, sparing the cow;

- two men try to steal the same bridge-builder’s axe (I’m surprised people still get close to this family) and they are attacked by the axe itself.

The well is a Grade II listed building, as you can see here.

3. The Lay of St. Cuthbert

“The Lay of St. Cuthbert” is one of my favourite pieces in this collection of weirdly funny falsely-medieval stories, because it has everything you need: a medieval banquet and devils who just want to party. The complete title of this story is The Lay of St. Cuthbert, or the Devil’s Dinner Party: A Legend of the North Countree, and it starts off with a Latin quote:

‘Nobilis quidam, cui nomen Monsr. Lescrop, Chivaler, cum invitasset convivas, et, hora convivii jam instante et apparatu facto, spe frustratus esset, excusantibus se convivis cur non compararent, prorupit iratus in hæc verba: “Veniant igitur omnes dæmones, si nullus hominum mecum esse potest!”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

‘Quod cum fieret, et Dominus, et famuli, et ancillæ, a domo properantes, forte obliti, infantem in cunis jacentem secum non auferunt. Dæmones incipiunt comessari et vociferari, prospicereque per fenestras formis ursorum, luporum, felium, et monstrare pocula vino repleta. Ah, inquit pater, ubi infans meus? Vix cum hæc dixisset, unus ex Dæmonibus, ulnis suis infantem ad fenestram gestat, &c.’– Chronicon de Bolton.

We’re basically starting off with a guy who’s really angry that his guests didn’t show up at his banquet and the food is going to waste: the plum-puddings are «bursting their bags», the mutton and turnips (presumably within the Scotch broth) are «boiling to rags», the fish is spoiled, the butter is oiled (for some reason), and «the soup‘s got cold in the silver tureen». One o’clock passes, and two o’clock. At three o’clock, the master of the house orders the dinner to be served and bursts out to say something along the lines of the Latin quote (“If no man wants to be with me, let all the demons come”).

‘Ten thousand fiends seize them, wherever they be!

— The Devil take them! and the Devil take thee!

And the DEVIL MAY EAT UP THE DINNER FOR ME!!’

Of course, demons do not need to be asked twice.

In a terrible fume

He bounced out of the room,

He bounced out of the house — and page, footman, and groom,

Bounced after their master; for scarce had they heard

Of this left-handed Grace the last finishing word,

Ere the horn at the gate of the Barbican tower

Was blown with a loud twenty-trumpeter power,

And in rush’d a troop

Of strange guests!– such a group

As had ne’er before darken’d the doors of the Scroope!–

3.1. The Guests

The original guests are mentioned, but we care very little about them: De Vaux and De Saye, Sir Gilbert de Umfraville, Poyntz and Sir Reginald Braye, Ralph Ufford (dead 1346) and Marney, De Nokes and De Stiles, Lord Marmaduke Grey, De Roe and De Doe (whom you can picture as Tweedledum and Tweedledee, I’m sure), Poynings and Vavasour (which are titles, more than names), Fitz-Walter, Fitz-Osbert, Fitz-Hugh, and Fitz-John, the Mandevilles (father and son), De Roos and De Clare. Some of them are Norman families, or actual people; others are nonsensical or tongue-twisters. As they never show up, even if they were tricked by a false note written by Stephen de Hoaques, we’ll pay no more attention to them.

Loosely disguised as his missing guests, they show up with claws, and tails, and beaks, and hoofs, and horns. And among them, the Devil himself.

Then their great saucer eyes —

It’s the Father of lies

And his Imps — run! run! run!– they’re all fiends in disguise

The roll call seems to be quite extensive too: Astarte and Hecate, the beauties of the party, are alongside Leviathan and Belphegor, Morbleu (described as «a French devil», which actually is just another variant of the curse “Sacrebleu”) and Davy Jones of Tredegar (described as «a Welsh one»), Demogorgon, Pan with his pipes and his fauns, Mammon and Belial, Medusa, Setebos (the god worshipped by the evil witch Sycorax in William Shakespeare’s Tempest) and Mephistopheles, Beëlzebub and, ultimately, Lucifer who ends up being the most drunk of them all. Should we want to talk about all of them, and for fear of not doing that in the correct order, I’m going ladies first and then I’ll use Peter Binsfeld‘s Treatise on Confessions by Evildoers and Witches from 1589, in which we have the concept usually known as “the seven princes of Hell”.

“– Here’s Lucifer lying blind drunk with Scotch ale,

While Beëlzebub’s tying huge knots in his tail.”

3.1.1. The Guests: ladies first

The triplet of demonesses Astarte, Hecate and Medusa, two of them defined “the belles of the party” and one of them popping up later where festivities are described, come from three different backgrounds, but varily associated with Greek mythology, and none of them is born as a demon in Christian culture.

Astarte is a form of Ishtar, a middle-eastern goddess of love, beauty, sex, war, justice and power: the closest thing you can get to the queen in the game of chess. Ishtar is the name among the Assyrians, while such a figure is also known as Inanna in Sumer, later taken on by the Akkadians, the Babylonians, and the Assyrians. She’s also known as Astoreth in Northwest Semitic and Astarte is the Hellenized form. She was the chief goddess of Canaanite and Phoenicians, and in Hebrew is sometimes referred to as plural, which might have led to some of the myths associated with the demon Asteroth (later). During the XVIII dynasty she was also imported in Egypt and incorporated into the pantheon: the Contest Between Horus and Set sees her as a daughter of Ra, alongside the similar goddess of war Anat. Plutarch, in his On Isis and Osiris, indicates that sometimes the name Astarte is used to identify the Queen of Byblos, who has the body of Osiris in a pillar of their palace.

Similarly, Hecate is a Greek goddess firstly appearing in Hesiod‘s Theogony (VIII Century) as the daughter of Zeus and the titaness Asteria, and as a mysteric goddess of nature, reigning indifferently on sky, earth and sea. Though she’s present in different Greek cults, including Athens’ as protector of the household, she’s not central nor appearing in the more widespread myths of the Greek pantheon and some scholars have argued that she might be of pre-Greek or foreign origin, Egyptian or Anatolian. It is Athens which starts associating her the underworld and to witchcraft, to crossroads and to some of the tropes we also find in folklore when dealing with demons. Apollonius of Rhodes in the Argonautica tells us that the witch Medea, who will grow up to be one of the most famous witches in Greek literature alongside Circe, was taught by Hecate herself. In Lucan‘s Pharsalia, the witch Erichtho also invokes Hecate by defining her the sum of three aspects one of which is Persephone, the goddess of the underworld.

Her original attribute is having three bodies or three forms, though this gets lost in later iconography: Pausanias in his II Century AD accounts of travels tells us that the first to represent Hecate this way had been the sculptor Alcamenes in V Century BC, but this is most likely the only named artist he was able to dig out of a bunch of popular depictions.

She’s a figure that fascinated both literates and painters: Shakespeare mentions her both in his Midsummer Night’s Dream and in Macbeth (1605), two of the works that mostly feature the supernatural, the magical and the witchy stuff, and she was painted a lot by symbolists, romantics and art nouveau. My favourite depictions of her this the sketch by William Blake (1759), but check out also this (much) earlier panel by Francesco Salviati (1545 approx.), and this animal depiction by Jusepe de Ribera. My second-favourite, however, has to be this painting by Maxmilián Pirner (1901).

Hecates by Maxmilián Pirner (1901)

The last of the demonesses is Medusa, the most famous of the three Gorgons with snakes for hair. She’s the the daughter of Phorcys and Ceto, two primordial sea gods, and she’s said to have lived on the island of Sarpedon, near Cisthene, not far from Lesbos. Her other two sisters are called Stheno, and Euryale. According to Aeschylus‘s Prometheus Bound, the three sisters are also related to the Graeae, also known as the Phorcides (the three sisters sharing one eye between each others).

Near them their sisters three, the Gorgons, winged

With snakes for hair—hatred of mortal man—

Perseus and the Graeae by Edward Burne-Jones (1892)

In the Metamorphoses, Ovid tells us a different story: Medusa was a beautiful girl, who was raped by Poseidon in Athena’s temple and the goddess punished her (because life really sucks) by transforming her hair into snakes and by cursing her appearance with the inability of being looked upon by any man who could live and tell. The same goddess would later help Perseus to kill her by giving the hero a mirrored shield in which he could look at the cursed creature in order to slain her. To add an additional troubling detail, Medusa was pregnant when Perseus beheaded, pregnant with her rapist’s child, and when he was beheaded from her body popped out both Pegasus, the winged horse, and the giant Chrysaor. In Apollonius Rhodius‘ Argonautica, in Lucan‘s Pharsalia and again in Ovid‘s Metamorphoses, it is also said that her blood gave life to the poisonous vipers as Perseus flew over the Sahara. In flying over the Libyan Desert, he also gave life to the Amphisbaena. Talking about pollution.

Medusa is a very popular figure in art, even more than Hecates and not only in symbolist and romantic art: the most beautiful and influential Medusa’s head is probably Caravaggio’s (who had a thing for beheadings, as you might know), who painted her beautifully on a shield (actually two of them, in 1596 and 1597) intended by the commissioner Francesco Maria del Monte as a gift for the Grand Duke of Tuscany. The Flemish painters were also fascinated with the topic in the XV Century (check this beautiful and anonymous work, for instance), following Peter Paul Rubens, take on the subject in 1618.

In later centuries, my favourite works have to be Arnold Böcklin‘s head of Medusa (1878), Alice Pike Barney‘s (1892), Maxmilián Pirner‘s, and Pavel Aleksandrovich Svedomsky‘s (1882). It is however one recent work who really nailed the subject: the beautiful Medusa with Perseus’ head by Luciano Garbati. The sculpture made lots of people unhappy. You can read about it here.

“I was thinking of Perseus, this man with all his gadgets, going there and having this victory. This difference between a masculine victory and a feminine one, that was central to my work. The representations of Perseus, he’s always showing the fact that he won, showing the head…if you look at my Medusas…she is determined, she had to do what she did because she was defending herself. It’s quite a tragic moment.”

3.1.2. The Guests: Princes of Hell

Belphegor is one of the seven princes of Hell and seduces people by suggesting them inventions and discoveries that will make them rich, although – according to a witch-hunter named Peter Binsfeld, whom I’m sure was a close friend of Adultery Pulsifer – he’s the demon of being lazy and chief demon of Sloth. Apparently our witch-finder held science and technology in the high regard we might expect from such a fellow. He is the disputer and opposes beauty, the sixth Sephiroth. In Collin de Plancy‘s Dictionnaire Infernal, Belphegor is the demon ambassador to France and his sworn enemy is Mary Magdalene. His origin, as it often happens, is the Moabite god Baal-Peor (see here). From a literary point of view, he plays roles in John Milton‘s Paradise Lost and Victor Hugo‘s Toilers of the Sea, but he has a chief role in Belfagor arcidiavolo by Niccolò Machiavelli, where we see him ascending to earth in order to find himself a mate. The story is the primary source for Ottorino Respighi‘s opera Belfagor (1923).

Leviathan is the Prince of Hell symbolizing envy, though his personification came later. In the original texts, in fact, more than a demon he’s a mythical creature, a sea serpent. He makes his apperance for instance in the Book of Job, where the tale takes clearly inspiration from the Ugaritic battle between Lotan, a servant of the sea god Yam, who is defeated by the storm God Hadad-Baʿal through a thunderstorm. He’s mentioned two times in the Book of Job (3:8 and 40:15–41:26, where you get a detailed description), two times in the Book of Psalms (74:14, 104:26) and in Isaiah (27:1). In later iconography, mostly in Anglo-Saxon art since 800 A.D., Leviathan is represented as the personification of the Hellmouth, or Jaws of Hell, a monstrous animal who eats the damned souls bound for Hell. His pal is Behemoth, not invited to this party: if Leviathan is sometimes represented as a crocodile, Behemoth is a very scary hippo. He’s mentioned in Herman Melville‘s Moby-Dick as a loose synonym of “sea monster” and even Milton doesn’t pay lot of attention to him, if not as a comparison for Satan’s size. William Blake‘s poem Jerusalem gives him more satisfaction and shows him alongside his friend Behemoth, in their respective forms of crocodile and hippopotamus, representing war by sea and land.

The Destruction of Leviathan by Gustave Doré (1865)

The second Prince of Hell we find at the party is Asmodeus, whom we catch having a slice of beef and who is the personification of lust. He’s the primary enemy in the Book of Tobit and his name comes from the Avestan aēšma-daēva, wrath-demon. He’s most likely of Zoroastrian origin. In the Book of Tobit, he has a bone to pick with Sarah, Reuel‘s daughter, and systematically kills seven of her husbands on her wedding night (she must have been really stunning, or people must have been really desperate, back then). When our hero Tobias is about to marry her, he gets the help of the archangel Raphael, who gives him a recipe to neutralize him (basically they place the heart and the liver of a fish on red-hot cinders and the smelly smoke is so bad the demon flees to Egypt, where Raphael can imprison him by binding him). In other texts of Biblical tradition, he’s a more jolly fellow, mostly after Bathsheba and Solomon‘s wives, and the King tricks him into helping him build the Temple of Jerusalem (a thing also recalled in the XIII Century Testament of Solomon). In the Malleus Maleficarum (1486), he’s the demon of lust. According to Johann Weyer, he’s the banker at the baccarat table in hell. Sebastien Michaelis, in his Histoire admirable de la possession et conversion d’une penitente (1612), says that his adversary is St. John, because of reasons. His favourite zodiacal sign is apparently Aquarius between January, 30th and February, 8th. So I guess we are a match. He commands 72 legions of demons, so he’s quite an accomplished fellow, although the description made by Collin de Plancy in his Dictionnaire Infernal is not particularly appealing. There are also theories of him being a half-blood, a cambion, fathered by King David with a succubus named Agrat bat Mahlat.

Wedding Night of Tobias and Sarah by Pieter Lastman (1611)

Mammon is also not exactly a demon per se: he came to be the Prince of Hell symbolizing greed, but the New Testament actually uses the word as a noun, meaning money, a noun that was not translated and as such was thought to be a guy. People who fostered that mistake (instead of learning a little bit of Hebrew), include very important people like Cyprian (bishop of Carthage), Saint Jerome, John Chrysostom, Peter Lombard, Piers Plowman, Nicholas de Lyra, Thomas Aquinas who even gives him a wolf as a ride. Albert Barnes even invents a Syriac demon with that name, in the vain attempt of appearing smart. And all this not to try and learn some Hebrew. I mean, I can understand that: I tried and it’s fucking difficult, but still, one should make an effort not to spit ball complete bullshit. Anyway, I’m very sorry for Mammon, who clearly does not exist: John Milton‘s Paradise Lost says he’s actually pretty cool with being in Hell (and now we kind of know why). He is also a character in Spenser‘s The Faerie Queene, where he oversees a cave full of treasures.

Beëlzebub is the highest Prince of Hell, personification of gluttony. He is mentioned in the Books of Kings and name comes from a Philistine god and is often associated with the Canaanite god Baal. He’s described as a flying demon in the Dictionnaire Infernal and called the “Lord of the Flies”, a thing taken up in recent fiction as we’ll see. John Milton‘s Paradise Lost sees him as the second-ranking fallen angel, right after Lucifer, and right before Astaroth. Johann Weyer, in his Pseudomonarchia Daemonum (1577), even narrates about an attempted rebellion of Beëlzebub against Lucifer himself (rebels would be rebels, I guess). He’s also a major character in in John Bunyan‘s The Pilgrim’s Progress. Beëlzebub fetures as the Prince of Hell in Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett joint work Good Omens and, thanks to the portrayal in the tv series, has gained quite a popularity. The look of the character in the series takes quite seriously the attribute as “Lord of the Flies”, and the character is seeing surrounded by them, with a giant fly as headpiece. All this is never actually seen in the book: Good Omen‘s Beëlzebub, which in the series is played by a woman and remarkably gender-neutral, is referred to as “he” by one of his demons and as “it” by the narrator and doesn’t make an appearance until the final chapter, when the demon rises to meet the Antichrist.

from the churning ground in the manner of the demon king in a pantomime, but if this one was ever in a pantomime, it was one where no-one walked out alive and they had to get a priest to burn the place down afterwards

In this occasion, the description of the character is similar to the heavenly counterpart Metatron: engulfed in blood-red flames. The flies are referred not in a visual way, as we see very little of the character, but in the voice of the character, described «like a million flies taking off in a hurry». Which, I bet, is not something pleasant to hear.

The best article purely taking the book into consideration seems to be this one. There could be some good illustrations of the character as Terry Pratchett’s “official” illustrator Paul Kidby was tasked in working on an official illustrated edition and he was very rigorous about the book (aside from the two main characters). I do not own this book, however, so I have no idea what his portrait of Beëlzebub looked like.

3.1.3. The Guests: last but not least

Belial, just like Mammon is also something that was never supposed to be a guy: in Hebrew, the word means something along the line of “worthless” and is generally used to describe something wicked. As such, the word is used not only for wicked men, but also for wicked ideas and counsels, and sometimes even for events and circumstances. Belial is personified a lot, however, in the so-called Dead Sea scrolls, the parchments found in the Qumran Caves and dating between III B.C. and the II Century A.D. In particular, the text known as The War of the Sons of Light Against the Sons of Darkness, a military manual disguised as an apocalyptic prophecy of war, tells the story of an upcoming war between the Sons of Light and the Sons of Darkness, and Belial is leader of the Darkness Army, composed of the Arabian Kingdom of Edom, the nearby Kingdom of Moab, east of the Dead Sea, the sons of Ammon, northern of Moab, the Nations of Amalek and Philistia and their allies the Kittim of Asshur. The battle is led by priests (on the Light side, of course) and is won by divine intervention (also on the Light side, naturally). The War of the Messiah, another Dead Sea Scroll, is sometimes considered the ending to the previous one. The term “Belial” is also appearing, with a less striking personification, in texts such as the Community Rule and the Thanksgiving Hymns.

Regardless of this, he’s described as a proper fallen angel in the apocryphal Resurrection of Jesus Christ (by Bartholomew) and grows up to be quite an important character in John Milton‘s Paradise Lost, where he’s described as a silver-tongued trickster.

On th’ other side up rose

Belial, in act more graceful and humane;

A fairer person lost not Heav’n; he seemd

For dignity compos’d and high exploit:

But all was false and hollow; though his Tongue

Dropt Manna, and could make the worse appear

The better reason…

He’s also mentioned in Robert Browning‘s Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister (1839), in Aleister Crowley‘s Goetia (1904) and in Anton LaVey‘s The Satanic Bible (1969), where he’s portrayed as a quite independent fellow (again, rebels would be rebels).

The best use of Belial in a popular culture product, as far as I can recall, was the character created in the fantasy shōjo manga Angel Sanctuary, which I was quite fond of, when it came out. Belial was there portrayed as a quite complex character, and most definitely one of the central characters in the second arc of the story. Dubbed “the Mad Hatter”, with an Alice in Wonderland crossed reference, was again a character with explicit gender neutrality.

Belial as drawn by Kaori Yuki.

Mephistopheles is another important demon who’s technically not one of the so-called Seven Princes of Hell, probably because he’s German and no-one wants to give too much power to a German, not even in Hell. He is heavily featured in German folklore and, most specifically, in the legends of Faust: he’s the devil in Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus and, though being mentioned also by Shakespeare in his Merry Wives of Windsor, that remains his primary and most important appearance. Goethe’s Faust of course takes up where Marlowe left and uses the same devil. In a certain way, he’s the first modern devil we encounter, having the characteristics of elegance and charme the other more antique demons are lacking, at least in their original forms.

Though Ludwig Spohr‘s Faust (1806) is mostly based on the original legends, lots of dramas and operas featuring Mephistopheles are using material from Marlowe of Goethe: this is the case for Hector Berlioz‘s La Damnation de Faust (1846), Charles Gounod‘s Faust (1859) and Arrigo Boito‘s Mefistofele (1868), which even features him as the title character.

3.1.4. The Guests: not really demons (but still at the party)

From now on, we step down from the traditional demons and we dive into more strange creatures. Our connection between the two worlds is Demogorgon, a world with which is usually described an underground lord, a dweller of down below. We are very clear that this is nor actually the name of the being, and is instead used as a filling for what otherwise is a taboo. According to Boccaccio in his Genealogia Deorum Gentilium, the Demogorgon is a very antique deity, antecedent of all the gods, but it’s pretty aknowledged that the name comes from a misreading of the Greek δημιουργόν (dēmiourgón). As Jean Seznec puts it in his Survival of the Pagan Gods, he is «a grammatical error, become god».

Regardless of him being an actual thing or not, as we have seen for Beial and Mammon, it takes just a couple of misinformed fools to create a demon. Our primary fools are Statius in his Thebaid, where a being is mentioned as «the supreme being of the threefold world», and Lactantius Placidus whom, in his commentary to this text, wisely explains «He is speaking of the Demogorgon, the supreme god, whose name it is not permitted to know», where the correct translation would have been «He is speaking of the Demiurge, whose name it is not permitted to know».

The Demourg is the unnamed creator of everything in some Greek traditions: this representation of a A lion-faced deity found on a Gnostic gem in Bernard de Montfaucon‘s L’antiquité expliquée et représentée en figures

From Boccaccio on, is all downhill. Demogorgon is mentioned by Christopher Marlowe in his Doctor Faustus (1590) as part of an invocation, by Edmund Spenser in his The Faerie Queene, and John Milton puts his name in the books too, though nither of them actually show us how this unnameable demon is supposed to look like. From the XVI Century on, however, things are starting to get more detailed: the Dutch demonologist Johann Weyer takes upon himself to tell us that Demogorgon is «the master of fate» in Hell, and Ludovico Ariosto, in his I Cinque Canti, even gives him a court in Himalaya from where he commands Fates and genies: every five years, his subjects are summoned back to his court within the mountain and give him a report of their doing and of their tempting of mortals. Ariosto’s work is used as a source of inspiration by Philippe Quinault, who wrote the libretto for Giovanni Battista Lully‘s royal opera Roland (1685): there, we meet again Demogorgon, in the role of king of the fairies and master of ceremonies. Since the play was performed at Versailles in front of King Louis XIV, we have no way of knowing if this was supposed to be a satire or a pun of some sort against Jean Jules Armand Colbert, marquis of Blainville, who was master of ceremonies at the time and was far from being an easy fellow.

Demogorgon also appears as a character in Percy Bysshe Shelley‘s Prometheus Unbound, where the being is described as the progenie of Jupiter and the Nereid Thetis, and eventually dethrones Jupiter. Described as a dark, shapeless spirit, the character is not defined in terms of gender.

As usual, we have to leave it up to the opera in order to have a work with Demogorgon as the main character: specifically, he’s the protagonist of the opera Il Demogorgone, ovvero il filosofo confuso composed by Vincenzo Righini (1786) on a libretto by Lorenzo da Ponte, which was originally intended for Mozart. The opera still features a piece written by Mozart, titled “Non tardar amato bene” (something along the line of “Don’t be late, my darling”).

In Dungeons & Dragons, Demogorgon is a self-proclaimed Prince of Demons, extremely powerful, humanoid but not so much, with two hyena heads with individual minds of their own, on top of snake-like necks, and long tentacles instead of hands. This particular creature has been recently made famous outside the roleplaying games world by the tv series Stranger Things, where the kids name their otherwordly enemy after the villain in the game they’re playing when shit starts to go down.

There’s a huge amount of weird stuff, around: I found this one here.

Davy Jones is another figure who doesn’t really belong here, but showed up at the party all the same. He comes from nautical folklore, alright, but he was never much more than a figure related to the expression “Davy Jones’ Locker“, meant to mean the bottom of the sea: the origin of the name is generally considered to be a mix between Saint David of Wales, considered the author of the most superfluous miracle in Wales, and the biblical figure of Jonah, more than central in nautical folklore. The earliest known occurrence in written form seems to be within the Four Years Voyages of Capt. George Roberts (1726) by Daniel Defoe, in which the expression seems to be a seaborn synonym for sending someone to Hell. In this sense, it’s the counterpart of Fiddler’s Green, a place where everyone is merry and dances non-stop, presumably drunk.

The figure of Davy Jones himself is described a couple of decades later by Tobias Smollett in his humorous The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle (1751), illustrated by that same George Cruikshank who also did The Ingoldsby Legends. In this story, he is described as a fiend taking various shapes, amongst which gigantic eyes, multiple rows of teeth, a pair of horns, tail, fancy shoes, and blue smoke sprouting from his nose.

One of George Cruikshank’s illustrations in 1832, as described by Tobias Smollett in The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle.

So it came to be that a figure never supposed to be more than a place turned out to be a guy, mostly in satirical and humoristic works. John Tenniel, few years before Cruikshank, also gave us a humoristic Davy Jones, merrily sitting on his locker, for the magazine Punch. Specifically, the merry fellow was reading a 1789 chart of Ferrol Harbor belonging to HMS Howe, a ship that had gone down in the harbour on November, 2nd 1892, presumably due to bad or outdated cartography, and he seems to be pretty satisfied with the fact that such charts are still in use.

“AHA! SO LONG AS THEY STICK TO THEM OLD CHARTS, NO FEAR O’ MY LOCKER BEIN’ EMPTY!!”

For the sake of justice, I have to add that Vice Admiral Henry Fairfax was charged for negligence and appeared in front of the Royal Navy court martial, but was acquitted of any charge on January, 7th 1893. Still, the satirical sketch stays.

John Tenniel’s sketch for Punch.

Other significant works depicting Davy Jones, mostly in the humoristic realm, include Everett E. Lowry‘s strip Binnacle Jim’s Visit to Davy Jones’ Locker (1905), the cover illustration for Thomas Russel Ybarra‘s Davy Jones’s yarns and other salted songs (1901). There’s literally little else: even in the comic strip Davy Jones, drawn by Al McWilliams from 1966 to 1968 as a spin-off of Sam Leff‘s Joe Jinks (1918–1953), the term is used evocatively due to the nautical and adventurous theme of the strip.

The character was of course made famous by Disney’s second and third movie of the Pirates of the Caribbean series, where he is depicted as a former captain, running a sort of sailor’s purgatory on board of the Flying Dutchman, another – yet unrelated – piece of nautical folklore. As far as I could understand, the look was studied by Crash McCreery, who did several versions, and later refined by Aaron McBride.

From the work of folklore to the world of plain fiction, another of the guests is Setebos, a deity worshipped by the evil witch Sycorax in William Shakespeare’s Tempest. In the text, it’s first mentioned by Caliban when the poor wreck realizes the magnitude of Caliban’s power and then invoked again when thinking about rebellion.

No, pray thee.—

[Aside] I must obey. His art is of such power,

It would control my dam’s god, Setebos,

And make a vassal of him.

There’s not much to go on about, but apparently it was enough for Robert Browning to compose a poem called “Caliban upon Setebos” (1864), in which Caliban reflects upon his brutal and cruel deity. The general idea seems to be that everyone has the god he deserve or, most likely, one makes up gods that are suited to one’s own disposition.

Similarly thin is what we have on a demon named Morbleu, as we have seen that it’s a play on words made by Richard Harris Barham on a variant of the French curse Sacrebleu.

The last mentioned deity is Pan, on which I already spent a lot of words with regards to The Wind in the Willows.

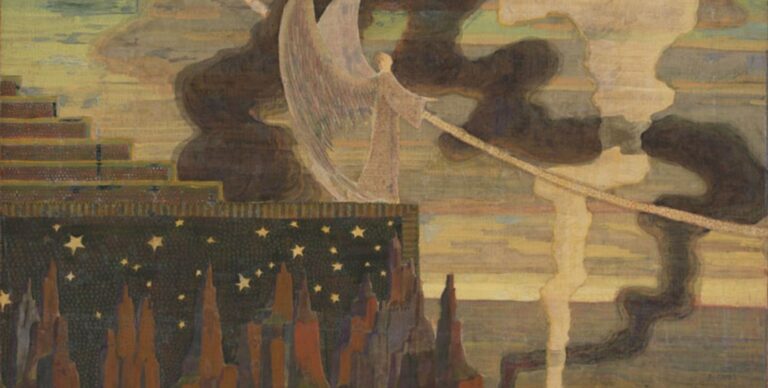

A plate from the edition on sale here.

3.3. The Menu

There’s little detail about the feast: we’re told there’s a lot to eat and to drink and most of the food is listed while it’s being spoiled by the legitimate guests’ unforgivable delay, but still we have something to go on. As main dishes, we have «fish, flesh, and fowl» (meaning poultry).

In the meat department, specifically, we have roast meat, boiled meat, sliced beef with mustard, a barbecu’d sucking-pig, stubble-goose in gravy, duck stuffed with onion and sage,

There’s even some vegetables, specifically leeks, though scarce and mostly monopolized by Davy Jones.

Before that, se have a selection of soups: boiled mutton and turnips, which we might refer to as Scottish soup, Soup à la Reine, soup-meagre.

All can be accompanied either by Scotch ale or wine.

As dessert, we have pancakes, plum-pudding, apple pie with custard.

And you can have hot coffee-lees for closure.

I’m no cook myself, but some of these recipes are to be found in old Victorian texts and I was able to dig them up.

3.3.1. Soup à la Reine

Among the usual sources for these kinds of stuff, we have a Rabbit Soup à la Reine within Eliza Acton‘s Modern Cooking for Private Families (1845).

Young rabbits, 3

water, or clear veal broth, 7 pints: ¾ of an hour.

Remains of rabbits

onions, 2

celery, 1 head

carrots, 3

Savoury herbs

mace, 2 blades

white peppercorns, a half-teaspoonful

salt, 1 oz.: 3 hours.

Soup, 4 to 5 pints

pounded rabbit-flesh, 8 oz.

salt, mace, and cayenne, if needed

cream, 1¼ pint

arrowroot, 1 tablespoonful (or 1½ ounce).

Wash and soak thoroughly three young rabbits, put them whole into the soup-pot, and pour on them seven pints of cold water, or of clear veal broth; when they have stewed gently about three quarters of an hour lift them out, and take off the flesh of the backs, with a little from the legs should there not be half a pound of the former; strip off the skin, mince the meat very small, and pound it to the smoothest paste; cover it from the air, and set it by. Put back into the soup the bodies of the rabbits, with two mild onions of moderate size, a head of celery, three carrots, a faggot of savoury herbs, two blades of mace, a half-teaspoonful of peppercorns, and an ounce of salt. Stew the whole softly three hours; strain it off, let it stand to settle, pour it gently from the sediment, put from four to five pints into a clean stewpan, and mix it very gradually while hot with the pounded rabbit-flesh; this must be done with care, for if the liquid be not added in very small portions at first, the meat will gather into lumps and will not easily be worked smooth afterwards. Add as much pounded mace and cayenne as will season the soup pleasantly, and pass it through a coarse but very clean sieve; wipe out the stewpan, put back the soup into it, and stir in when it boils, a pint and a quarter of good cream* mixed with a tablespoonful of the best arrow-root: salt, if needed, should be thrown in previously.

Should you not like rabbit, there’s a similarly called recipe in the same book, featuring oysters.

3.3.2. Soup-meagre

It’s generic term for a light soup, or a soup with no meat. A recipe for what is called Meagre Soup can be found within The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy by Hannah Glasse, first published in 1747 and one of the most popular cookery book of its time. It’s a meat-free soup, as I was saying, particularly popular for the period called Lent, the period of penance separating carnival from Easter when meat is theoretically not allowed. You can find it here. This is how the text goes:

Take half a pound of butter, put it Into a deep stewpan, shake it about, and let it stand till it has done making a noise; then have ready six middling onions peeled and cut small, throw them in, and shake them about. Take a bunch of celery clean washed and picked, cut it in pieces half as long as your finger, a large handful of spinach clean washed and picked, a good lettuce clean washed, if you have it, and cut small, a little bundle of parsley chopped fine; shake all this well together in the pan for a quarter of an hour, then shake in a little flour, stir all together, and pour into the stewpan two quart of boiling water; take a handful of dry hard crust, throw in a tea spoonful of beaten pepper, three blades of mace beat fine, stir all together and let it boil for half an hour; then take it off the fire, and beat up the yolks of two eggs and stir in, and one spoonful of vinegar pour it into the soup and send to table. If you have any green peas, boil half a pint in the soup for change.

The main ingredients seem to be:

butter, half a pound

onions, six middle-sized

celery, a bunch

spinach, a handful

lettuce (if you have it)

green peas (if you have half a pint of them)

parsley, a little bundle

a little flour

dry hard crust (a handful)

beaten pepper (a teaspoon)

mace (three blades)

the yolks of two eggs

vinegar, one spoonful

Frontispiece for The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy by Hannah Glasse

3.3.3. Mutton and Turnip

This references to two typical ingredients for different soups, sometimes called Scotch Soup, dating back to al least the XVII Century. The most interesting recipe is probably the one commonly called Harico, Herrico or Haricot. It sometimes it includes potatoes, sometimes it has wine and bread (for instance accordingly to the English Oxford Dictionary). That invaluable on-line resource which is The Foods of England provides a couple of historical resources like The Experienced English Housekeeper by Elizabeth Raffald (1769), where you have two recipes.

I give you the second one, which seems to be the less horrible.

Take a neck of mutton and cut it into chops, flour them, and put them into a stew-pan, set them over the fire and keep them turning till brown, then take them out and put a little more into the same pan, and keep it stirring till brown over the fire, with a bunch of sweet herbs, a bay leaf, an onion, and what other spice you please; boil them well together, and then strain the broth through a sieve into an earthen pan by itself, and skim the fat off which done, is a good gravy, then add turnips and carrots, with two small onions, a little celery, then place your mutton in a stew-pan with the celery and other roots, then put the gravy to them, and as much water as will cover them: keep it over a gentle fire till ready to serve up.

There’s also a couple of “more recent” recipes taken from Pot-luck, or The British home cookery book (1911), one of the many cookbooks written and published by May Byron.

3.3.4. Stubbled Goose

Stubbled Goose is a way to define a young goose that has been fed mostly on grass stubble and leftovers from the harvest (gleanings), and it’s also called Green Goose. It’s in contrast with the Christmas Goose, which is traditionally fed with corn. There are different ways to cook a stubbled goose, but one of these ways is Michaelmas Goose, is a roasted goose typically cooked for the feast of St Michael and All Angels, also called Michaelmas, on September 29th (though in Suffolk it’s apparently celebrated on October, 4th and in Norfolk on October, 11th). It is the beginning of one of the four Law Terms, and a very important one, since it’s the first day of the farming year, or the end of the harvest depending on how you want to look at it, and traditionally the goose was part of the payment (also sometimes called “a present”) from farmers to their landlord. You can find different versions of the recipes and references. Elizabeth Moxon in her English Housewifry (1764) gives us two versions for a sauce, for instance, based on sorrel, butter, and gooseberry. Mrs. Maria Eliza Ketelby Rundell in 1807, within her A New System Of Domestic Cookery, gives us other two versions based on sorrel. You can find all four of them here.

Take half a pint of sorrel-juice, two glasses of white wine, a nutmeg quartered, a cupful of fried crumbs, and two lumps of sugar; let all boil together, then beat it

smooth, adding a piece of fresh butter, and serve it very hot in a tureen, or in the dish with the goose: it should not be made too thick with the bread-crumbs, and if much acid should not be approved, the wine must be equal in quantity to the sorrel-juice.

There’s also another sauce here, originally included by Isabella “Mrs. B” Beeton in her Book of Household Management (1861) and still it’s based on sorrel. Should you be wondering, sorrel is a sort of a wild spinach.

Should you be looking for recipes of the goose itself, you be looking to taste a Michaelmas Goose, here you can find a list of places that were reviving the tradition (at least before the pandemic).

3.3.5. Sucking-Pig

Similarly to the “stubbled Goose”, the expression “suckling pig” is simply a way of describing a young pig, still feeding on mother’s milk. There are different recipes to cook it, in traditional England, and this specific one is roasted. You can find a recipe, for instance, The Cook’s Oracle‘ by the English journalist and celebrity chef William Kitchiner (1830) and it’s published here and I’ll give you just a quote so that you can appreciate the sadistic detail of Kitchiner’s prose.

To be in perfection, it should be killed in the morning to be eaten at dinner: it requires very careful roasting. A sucking-pig, like a young child, must not be left for an instant.

Caricature of Richard Martin, William Kitchiner, Samuel Phillips Eady: Martin’s Bill in Operation (1924), by the same George Cruikshank which seems to be the hero of this article (courtesy of the Wellcome Library in London).

3.4. How to break up the party

Now that you have the guest list and a glimpse of the menu, and you know how to call for them, you might also need to know how to get rid of the merry flock, especially when they start playing rugby with your toddler son, as it happens to our guest.

In that broad banquet hall

The fiends one and all,

Regardless of shriek, and of squeak, and of squall,

From one to another were tossing that small

Pretty, curly-wigg’d boy, as if playing at ball:

Yet none of his friends or his vassals might dare

To fly to the rescue, or rush up the stair,

And bring down in safety his curly-wigg’d Heir!

Just as he has summoned the Devils himself, our despairing host can find no-one brave enough to face that hellish horde and save his son, not even in front of the offer for fifty pounds, and eventually turns to the supernatural. He invokes St. Cuthbert, after a few troubles in remembering his name, and hastily vows to do whatever the Saint wants and to build him a shrine of unparalleled magnificence.

Bring him back here in safety!– perform but this task,

And I’ll give!– Oh!– I’ll give you whatever you ask!–

There is not a shrine

In the County shall shine

With a brilliancy half so resplendent as thine,

Or have so many candles, or look half so fine!–

Unexpectedly, the Saint agrees (and has even to question about the quality of the wax), but the demons won’t go away, since they were actually invited.

They agree to leave after they are done eating, and the Saint can even make them promise that they will not steal the cutlery and plates. However, the leader of the band parts with a rather gloomy toast:

But, Gentlemen, ere I depart from my post,

I must call on you all for one bumper — the toast

Which I have to propose is,– OUR EXCELLENT HOST!

— Many thanks for his kind hospitality — may

We also be able,

To see at our table

Himself, and enjoy, in a family way,

His good company down stairs at no distant day!

The story ends with four facts and summarizes them into a morale:

- Do not invite the devil at your house, because when you do there’s really no point calling after saints and such;

- You should really keep an eye out for nannies who leave heirs laying around when devils are afoot;

- Sir Guy, the lord of the house, spends all his fortune to build and maintain the shrine of St Cuthbert and, even if eventually he’s able to slip through the devil’s fingers and escape the invitation to dine downstairs, so you really shouldn’t light your candles on both ends;

- when invited to dinner, try not to be late.

You can read the full story here. It’s really weird and kind of funny.

3 Comments

Pingback:A Lay of St Nicholas (another Ingoldsby Legend) – Shelidon

Posted at 00:03h, 21 February[…] “lay” is a form of poetry, as I have had the chance of explaining when I wrote about “The Lay of St. Cuthbert”, and this one is part of the works known […]

Pingback:#AdventCalendar Day 10: Rabbit Soup à la Reine – Shelidon

Posted at 00:05h, 10 December[…] Today I bring you an old recipe reinterpreted through a Victorian’s eyes. If you’ve been following me for a while, you’ve seen this already in one of my long articles on the Ingoldsby Legends, specifically the one on The Lay of St Cuthbert. […]

Jack

Posted at 15:09h, 09 SeptemberVery interesting article; I came this page having finished the Ingoldsby Legends, (unfortunately not illustrated). I looked into the history of Vavasour when drinking a bottle of wine from New Zealand called Vavasour.

The Vavasour family came over with William the Conqeuror and settled at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hazlewood_Castle

Family tree at the supposed time of the feast:

https://www.ourfamtree.org/pedigree.php/Henry-Vavasour/79926#a32171325