Fantasia’s Russian Dance

On this long, long night of stories, I would feel bad for leaving out the Russian dance, so here we are. It’s not one of my favourite pieces, so I’ll most likely be brief. 3. The Nutcracker Piece by Piece (5) 3.5. Russian Dance: the music The Russian dance featuring in the Nutcracker is technically […]

On this long, long night of stories, I would feel bad for leaving out the Russian dance, so here we are. It’s not one of my favourite pieces, so I’ll most likely be brief.

3. The Nutcracker Piece by Piece (5)

3.5. Russian Dance: the music

The Russian dance featuring in the Nutcracker is technically a Trepak, based on a traditional Russian and Ukrainian folk dance also known as Tropak. It was traditionally said to be played by blind itinerant musicians called kobzars, on string instruments called banduras and bandurkas (no, I’m not making fun of you) and Tchaikovsky used it two times: in the Nutcracker and in his Violin Concerto in D major. A Trepak also features as one of Modest Mussorgsky‘s Songs and Dances of Death, a song cycle for voice and piano based on questionable poems by Arseny Golenishchev-Kutuzov.

The dance is slightly different from the equally traditional dance Hopak (again, I’m not making fun of you), which is slightly more used: there’s a hopak in Modest Mussorgsky‘s The Fair at Sorochyntsi, in Tchaikovsky’s opera Mazepa, in Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov‘s May Night,in Ivan Kotlyarevsky‘s Natalka Poltavka and in Cesare Pugni‘s The Little Humpbacked Horse (no, I had never heard of him either).

In the Land of Sweets, the Russian Dancers are representing Candy Canes, but the dance was originally titled Danse des Bouffons. According to Jennifer Fisher in her Nutcracker Nation: How an Old World Ballet Became a Christmas Tradition in the New World:

“Petipa’s written instructions called for: ‘”Trepak, for the end of the dance, turning on the floor,’ referring to the athletic feats of Russian character dance. But evidently Ivanov didn’t like the variation he came up with in rehearsal, and when someone suggested a hoop dance instead, the dancer Alexandre Shiryaev choreographed his own solo.”

As you might remember, the Petipa in question is Marius Petipa, choreographer of pretty much everything significant of his time, while Lev Ivanov was his Second Balletmaster.

Alexander Shiryaev is a character we haven’t met yet, and an interesting one at that: he was a dancer, balletmaster and a choreographer, but most importantly he was a pioneer animator who is credited with no other than the invention of stop motion (which, as we’ll see, was also used in Fantasia‘s last Nutcracker piece: the Waltz of Flowers). He was the grandson of the same Cesare Pugni I had never heard of (it’s amazing how everything seems to come together, sometimes) and his mother Ekaterina Ksenophontovna Shiryaeva was a member of corps de ballet at the Bolshoi Theatre. He specialized in jester dances: not only he performed the buffoon in The Nutcracker, but he also did the dance of jesters and skomorokhs in The Merchant Kalashnikov by Anton Rubinstein, the buffoon dance in Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov‘s Mlada, Harlequin in Riccardo Drigo‘s Les millions d’Arlequin and Carabosse (you would say Maleficent, wouldn’t you?) in The Sleeping Beauty.

His animation career started filming ballets and soon he started recreating ballets in his apartment by using clay or papier-mâché puppets and shooting pictures of their poses, just as we do in modern stop motion, several years before Ladislas Starevich, who is generally credited to be the inventor of the technique, started working alongside the same idea.

3.5. Dancing Thistles and Orchids

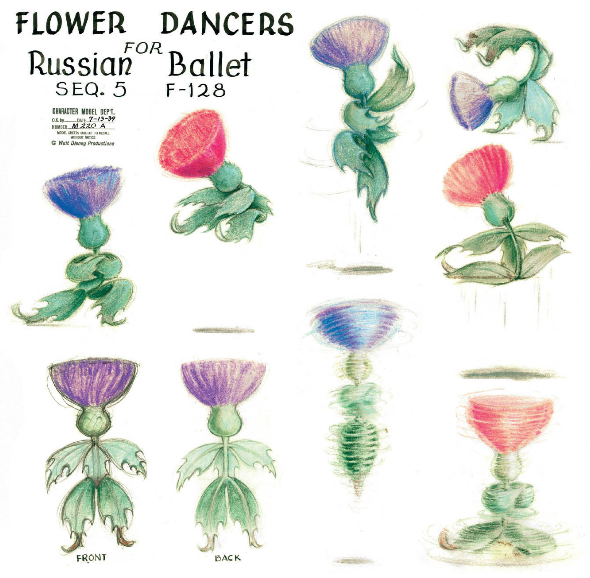

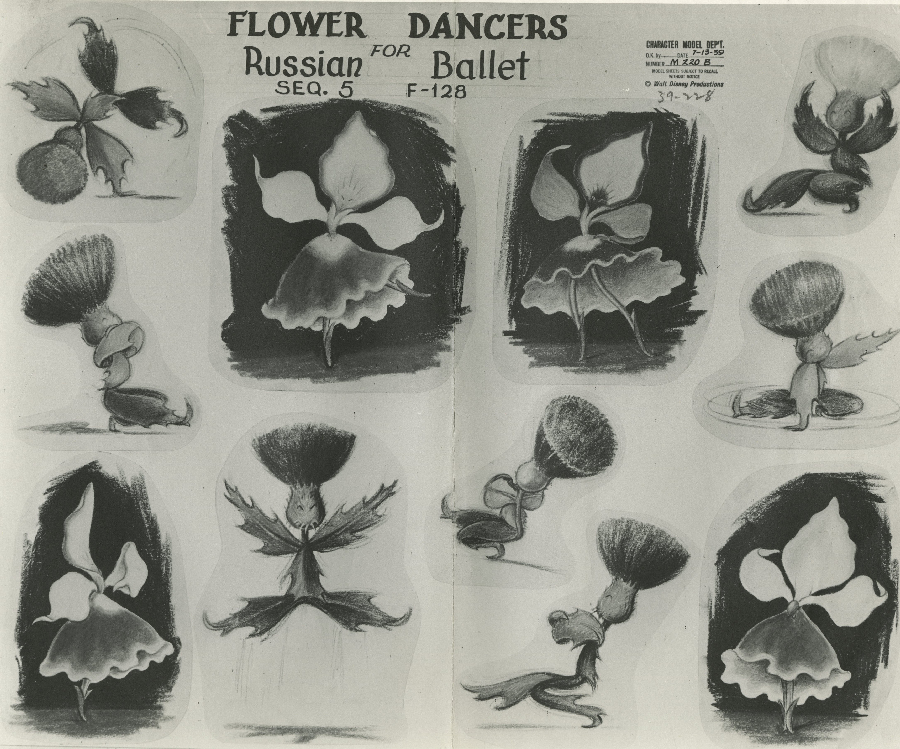

As I have previously mentioned, lots of what will become the Russian Dance in Fantasia had been studied by Bianca Majolie and Ferdinand Horvath in the famous never-released Silly Symphony The Flower Ballet. Sylvia Holland would take up where they had left and, with her assistant Ethel Kulsar, her first proposal to Joyce Coles, a ballet dancer revolving around the studios, was revolving around three characters: a tall male flower, a white columbine and a Pierrot-like character made from a bleeding heart. She had also written a fairy-story with a young flower storming a castle in order to win the heart of a white orchid princess, and she proposed than again for the Russian Dance.

“The Russian Dance takes place in the Czar’s castle, lighted with candles and all wearing costumes, and huge shadows cast by the candles.”

– Sylvia Holland’s pitch to Walt Disney for the Russian Dance

John Canemaker recalls the story in his book about Disney artists:

I believe that it was [Sylvia Holland’s] idea that the thirstles resembled Russian dancers. She and the two women, Ethel [Kulsar] and Bianca Majolie, went out and found some weeds growing in vacant lots next to the Studio, and came back with those and suggested to the guys… that they could be dancers.

Johnny Walbridge was also assigned to work at the suite and, among the characters he developed alongside the goldfish in the Arabian Dance, and the Chinese mushrooms, we also see the thistles in the Russian Dance.

Thanks to the work of these artists, we find ourselves with high-kicking thistles, whose petals are arranged to resemble the high fur hat of Cossacks, and multi-coloured orchids dressed in the traditional costume of Russian peasant girls. The traditional costume they mimic with their headdress is called kokoshnik (for married women) or povyazka (for maidens) and it complements the sarafan, the long, traditional, colourful part of the dress. In particular, the triangular headdress is called kika and is typical of Kostroma, on the river Volga, where other regions have differently-shaped hats (see the seven different types here).

By the end of the piece, the dancer collapse as exhausted and they turn back into thistles.

What’s a thistle, precious?

Thistles are the floral emblem of Scotland, and for a very good reason: according to legend, the Battle of Largs (1263) was initiated by one of the Norse invaders unwillingly letting out a cry after stepping barefoot on a thistle, and the military event marked the beginning of the retreat for King Haakon IV of Norway (Haakon the Elder) who had control of the Northern Isles and the Hebrides and wanted to gain a similar control on Scotland. It has been the National symbol since the reign of Alexander III (1249–1286) the highest chivalric order of Scotland is called The Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle (something that wouldn’t suit ill in a Terry Pratchett’s novel). The Scots Guards‘s regimental badge also has a thistle right in the middle.

To these days, the Rose, Shamrock and Thistle symbol is used to represent the union between England, Scotland and Ireland (nobody cares about Wales, apparently).

For some reason, thistles are also the symbol of Lorraine, a region in northeastern France, perilously close to Luxembourg and Germany. This apparently has to do with the fact that, in the Middle Ages, the thistle was an emblem of the Virgin Mary because someone saw its white sap and thought “hey, look mother’s milk”. People are not well. René of Anjou decided it was a good lustful symbol for sex, so he adopted it as a personal symbol, and passed it on to his grandson, René II Duke of Lorraine, who in turn imposed it to a whole region of unsuspecting people. After the Battle of Nancy in 1477, the Duke’s motto became “Qui s’y frotte s’y pique” (who touches it, pricks himself). It still is the official symbol of Nancy and I’m sure they think it’s just a pretty flower, and not a metaphor for holy tits.

Qui s’y frotte s’y pique

There’s a French artist called Grandville who did the illustration of a thistle (Chardon, in French) in his Fleurs Animées, which is super weird and was written around 1847 by Taxile Delord and Alphonse Karr. I suggest you also take a look at his Tulip, and his Kaktus.

If you’re looking for a botanical illustration, my personal favourite has always been the illustrated atlas Köhler’s Medicinal Plants. However, it’s also worth mentioning that there’s another set of significant illustrations featuring thistles, as they happen to be the favourite food of Eeyore in A.A. Milne‘s Winnie-the-Pooh (1926) and The House at Pooh Corner (1928), so you have some thistle illustrations by E.H. Shepard.

Thistles also have their fair share of appearances in fairy-tales: in some versions of the folk-tale, Tom Thumb is dressed in thistle by the Fairy-Queen, and in Norse folk-tale The Twelve Wild Ducks, the main character is told by her brothers that she can set them free by weaving them cloths of thistle-down without crying. Hans Christian Andersen wrote the tale “What Happened to the Thistle” within a collection in 1860, and within Flower Fables by American novelist Louisa May Alcott, her first book published in 1854, there’s a story called Lily-Bell and Thistledown and you can read it here.

Thistledown was as gay and gallant a little Elf as ever spread a wing. His purple mantle, and doublet of green, were embroidered with the brightest threads, and the plume in his cap came always from the wing of the gayest butterfly.

But he was not loved in Fairy-Land, for, like the flower whose name and colors he wore, though fair to look upon, many were the little thorns of cruelty and selfishness that lay concealed by his gay mantle. Many a gentle flower and harmless bird died by his hand, for he cared for himself alone, and whatever gave him pleasure must be his, though happy hearts were rendered sad, and peaceful homes destroyed.