Architecture and Gaming – What’s with all the hype?

Architecture and Gaming What’s with all the hype? As I was saying here, when I was presenting the new proposed trends for Autodesk University this year (did you vote yet, by the way?), finding a better way to communicate your architecture, in a more immersive way for all stakeholders, seems to be a new frontier. Now, […]

Architecture and Gaming

What’s with all the hype?

As I was saying here, when I was presenting the new proposed trends for Autodesk University this year (did you vote yet, by the way?), finding a better way to communicate your architecture, in a more immersive way for all stakeholders, seems to be a new frontier. Now, I hope nobody forgets that we are still actually trying to bring the majority on board with BIM, but I am amused enough by the concept. It has been a topic for quite some time now: for some reason, Minecraft has played a strong role in this, and if you’re curious about original trends using gaming engines I suggest you check out the work of game developer Jose Sanchez (there was an article about him on DeZeen, here).

..

This hype is often about replacing design tools with gaming tools, for a more intuitive approach or to integrate the perception of the space within the design process. It might be a very nice way to harvest feedback from the community, as it has been attempted to do by the United Nations with the Block by Block programme in Kenya, Mexico City, Kosovo and Mumbai. However, as Steven Schkolne has recently wrote in this very interesting article for the Huffington Post, the actual buildability of these kind of projects is in question. He makes an argument about digital tools influencing the way projects get built.

You see, real-world fabrication is for me where games begin to definitively mark architecture. […]

A building built in Minecraft is sure to be blocky. A building made from the elements of Little Big Planet, Super Mario Bros., or Borderlands would no doubt have a fantastical nature to them. I can see Age of Empires inspiring post-modern revitalizations of a slew of historical models. And of course we have games like Fallout and Gears of War to inspire architectural visions that border on post-apocalyptic nightmare.

See, the mistake here is in thinking that this is something new for architecture. If you know us by now, you’ve already heard a sermon about how tools (digital and non digital) have always influenced architecture, since the adoption of the proportional compass. Architecture, though, has a history of adopting tools that have been developed for other reasons: it’s not a driving force of innovation, it rarely has been. Even when cathedrals were driving the economy of their world, what was actually driving it was religion. Therefore I am not surprised if we are adopting tools from the gaming industry for our own purposes. The trick is that, well, the purpose is not what they think it is.

The above mentioned article states: «When using traditional CAD systems, architects are always outside of the building — somewhat like building a Lego model, architects build from that outside, as if gods. Working in games like Minecraft, architects of the game world create buildings from the inside». Now, thing is you can’t render those approaches as mutually exclusive: whether you need to check the first-person experience within your space, you still need to take a step back and work at a larger scale, and then going in again. Traditionally that was a check you did with photorealistic renderings. The real revolution is in tools like Enscape, specifically built for architecture but with a gaming twist to it: the rendering is a carefully selected scene, usually pimped up in order to sell your project. Rendering is expensive, therefore it’s mainly a commercial tool. An immersive experience that is seamless and inexpensive to the process encourages the designer to constantly immerse himself in his project, therefore introducing the kind of innovation that is being claimed here. It’s not that architects don’t take an immersive approach because they don’t want to: it’s because they can’t. If they have to wait for half a day for their project to export towards some sort of visual rendering engine, they won’t. It will be treated like rendering: a commercial tool applied to the project when it’s finished, just in order to sell it. And if they have to work with tools that don’t take into account the buildability of what they are creating, the project might have been checked with an immersive perspective but it’s going to be a disaster nonetheless.

As it is clearly stated in the manifesto of the Plethora Project, the idea of pushing an architecture that assembles blocks through a simple tool is strictly political. They call it Architectures for the Commons and «is an ideology that emerges as a form of resistance to a parametric agenda and the socio-economical implications it entails». The problem here is that, while it seems to promote a more active participation in «the decision-making process of public architecture», it doesn’t do so through a review tool (which we would badly need) but proposes a simplistic creation tool.

This is not what I am going to talk about here.

I am all about public activism and I do believe we need efficient and accessible collaboration tools for the end users to give their feedback but I don’t believe this is what we are getting here.

Gaming engines to me are, for now, a powerful review tool.

And this is the approach I am taking here.

Gaming Engine and Immersive Experiences

Whys, Whats and Whos

These two concepts are often presented together, as if you can’t have the one without the other. Now, if you think about it, it’s completely not true. Isometric games are completely non-immersive and they resemble Revit more than you could have thought, in some ways. What makes Diablo different than your average skyscraper in Revit is the experience. Somebody took the bother of designing an experience and the environment is built around it. And no, this does not get solved by throwing a couple of zombies into your Revit project, you naughty boy.

What’s really interesting in using gaming technologies in architecture, on a first very basic level, is that they are equipped to enhance the experience of the environment, but this is worthless if you don’t take your time to (and hire somebody capable of) design that experience. Without proper planning, the use of a gaming engine will just translate into a boring stroll throughout a boring project.

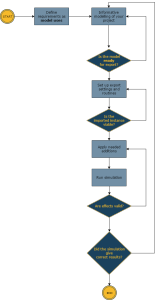

There are many reasons why you might look for a 1st-person experience, many aspects you might want to check. Each of these aspects translates into a “model use”, in its own way.

Are you looking to double-check that your project is lit enough? You need to treat it like a lighting analysis, and take into consideration:

– that all your components have a correct light source or that you wisely used self-illuminated materials;

– that your project is correctly referenced in the real world;

– that clouds and air density represent what you are most likely going to get in real life;

– that materials are correctly set in terms of colour, reflectivity, bump and everything.

Do you want to simulate the experience of a particular user within the project? You need to plan his/her hypothetical pathway.

Do you want to run an immersive experience for a concert hall? Well, you can’t plan to do it silently.

And so on.

In short, the whys and whats are the first thing you need to consider.

Additionally, there’s the whos.

Now, I said that using a gaming engine doesn’t necessarily equals using a 1st person experience. On the same line of thought, using a 1st person experience doesn’t necessarily equals doing it in an immersive environment. You can enjoy a 1st person simulation while sitting comfortably into your meeting room chair or you can kick right into the model but this will require a headgear of some sort.

Now, this kind of experience is to be tailored upon the user you are aiming to impress and if you aim to engage a larger audience you might want to check some stats regarding the virtual reality market before doing so. I don’t presume to have the truth here, but here are some major factors you might want to take into consideration while choosing whether you want the experience to be immersive or not:

1. Age it’s a thing, but not the way you mean it. Over 50s tend to be more curious and open than people in their mid 40s. Youngsters are most likely to enjoy the idea, though in Italy we still suffer a little from the social stigmatization of what might be considered nerdy. I have had surreal experiences where whole classes were denying to having ever played a videogame until I proved them wrong.

2. Health is another thing. If you’re client is wearing glasses, offering a headset it’s more than likely to be a bad idea. There are also things you might not know about your audience. If you want an idea, read up some of the indemnifications you have to sign if you enter a virtual reality experience nowadays. You need to be as fit as a fiddle, both physically and mentally. It’s not something to be taken lightly: you don’t want your client feeling sick in the meeting room.

3. Social implications are also a thing. Like the main thing, actually. If your client is a caliph, a king or a demi-god, he probably won’t give a damn and put on the headgear and have fun. On the other hand, if you’re trying to reach a large public and you create an immersive experience in a public space everything is most likely to be fine. As with the age, inbetween happens to be the problem: if your client is an executive and he came over with his entourage it’s less than likely that he will accept to put a headgear on while everybody else stares at him and possibly makes fun. Sensory deprivation is instinctively connected to humiliation and abuse. Also, headgear are nowadays more connected to videogames. If you are a serious businessman you can’t be caught wearing one of those, can you?

4. It messes with my hair and make-up. Just saying.

When

There’s also a “when” factor to take into consideration. As long as the technology doesn’t allow us for seamless experiences, these kind of experiences are viable in two ways:

– for workshop-like meetings, both internal or with the client, through which you can verify the design intention;

– for presentations, through which you showcase the aforementioned design intention;

– for running specific simulations.

In all cases, is something you prepare for a checkpoint or the end of a phase, pencils down. It can’t be randomly placed in the design process but, just as renderings, it needs to be carefully planned. You won’t be able to track changes occurring in the authoring tool while you are using the simulation tool. Of course this is a limit that needs to be overcome in order to effectively implementing these tools as production tools. Of course this is our goal, because if you don’t integrate it within production you will raise your chances of work at a loss.

The Game Engines out there

If you want to know which viable options you have out there, I suggest you take a look at the video below, by Joe Banks, and that in general you follow his work.

..

There have been great classes all around BILT, about Virtual and Augmented Reality for Architecture through a game engine: check out the material, when it comes out, or even better you can attend the North America edition in Toronto (August 1st-5th): they tell me it’s going to be amazingly cool.

Now, I’ve been experimenting for a while now and, though I’m no expert (yet), I think I’ve got my head wrapped around a couple of things. By now, I’ve developing with:

Good news is that if you managed to learn Dynamo you can beat them all. Bad news is that the real challenge (as usual) it’s not geometry and it’s not animating a decent experience for your client: is dragging your damn data along with you. Meaning I can import the project of my hotel into Stingray in the glimps of an eye, and create a first-person shooter around it in no time, but I want to have model and price of those Revit families along with me, so that when you shoot them up you will be charged the correspondent amount of money. Can it be done? We’ll see.

Weiter so ! Netter Beitrag :)