The exhibition has been going on for a while, but I’ve been:

- depressed;

- busy with my forced relocation;

- depressed;

- busy with looking for a construction crew that can handle the repairing works in my house;

- depressed;

- busy with work;

- depressed;

- away on a journey.

Said journey helped and I’m not depressed anymore (I know, that’s not how it works), plus I have time on my hands because my novel is on hiatus waiting for feedback from beta readers, and I managed to attend the second to last week of the thing.

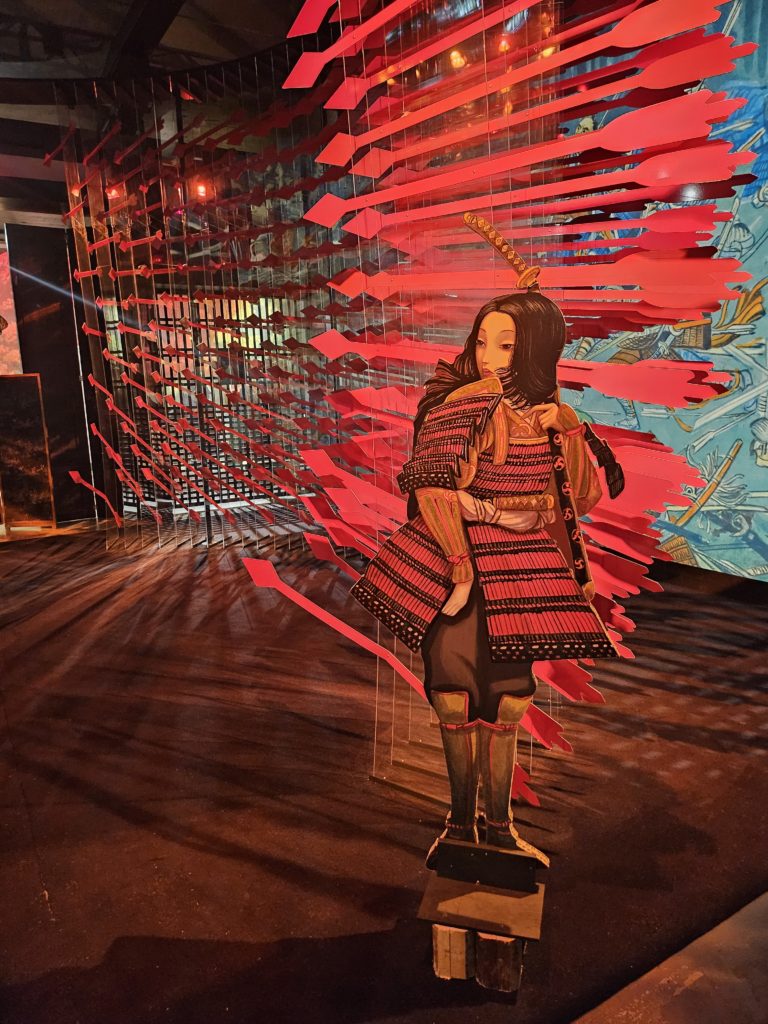

Stories of Women Samurai is the second exhibition Tenoha dedicates to a book by French illustrator Benjamin Lacombe, the first being a combination of two books I talked about here, and it goes back to the origins of previous exhibitions such as the one on Tokyo Storefronts, with giant reproductions of works by Mateusz Urbanowicz: it’s less ambitious, in a way, with more focused projections and almost no animatronics (and I can’t blame them: they were a maintenance nightmare).

And before I proceed, let me clarify that this is what I mean when I say “less immersive” and “more focused projections”.

I also tried to upload it here, hoping it would adapt it into a horizontal frame, but YouTube is trying to be FuckTok, these days, so shorts can’t be embedded in a web page.

The video mapping is done by the digital creative company Hitohata, and it shows scenes from the city of Okazaki, its history and its evolution into modernity, on top of the reproduction of a samurai armour alluding to Tokugawa Ieyasu, the founder of a Shogunate which would rule from 1603 until the Meiji Restoration in 1868.

Here’s another short from a side angle (and here it is too):

As a general principle, the exhibition is much more focused in lending you stuff so that you can take pictures of yourself in the different rooms, either wearing a kimono, wielding a katana or sporting a fan. Or all of the above.

No, I didn’t do it.

Still, the entrance provides a good decompression room so that you can get into the mood of the exhibition.

Drawings and stories are present too, inside, though they’re much more out-of-the-way, and they managed to concoct an activity even I would enjoy: you can buy a small notebook at the entrance, and fill it with different stamps you can find around the exhibition.

But what is featured in the exhibition? Which are the women in the book? Well, you’re in luck: I was wise enough to keep it out of the relocation boxes.

Onna-musha

First of all, in pre-modern Japan there’s a specific word for a woman warrior and it’s onna-musha. They were not wayward women pretending to be men and sneaking into battle: they were proper members of the warrior class (the bushi), and were properly trained to use weapons. Being female guards outside of harems was only one of their fields of employment. In that case, they were referred to as besshikime (women with a different style).

Some of them are considered mythical figures, such as Tomoe Gozen who fought in the Genpei War (1180–1185). Some others’ existence is considered more plausible, like Ichikawa no Tsubone who defended Kōnomine Castle with her ladies-in-waiting during the Sengoku period. For some others, we have actual historical evidence.

Ōhōri Tsuruhime (1526–1543)

The first set of drawings is dedicated to this warrior either from the Sengoku period (1467–1638) or the Muromachi period (1336–1573), depending on which group of scholars you stand with. Tsuruhime was born the daughter of a priest, the chief priest of the Ōyamazumi Shrine on the island of Ōmishima. Ōhōri Yasumochi, the priest, had two other brothers: Tsuruhime claimed she had received divine inspiration, but she was living in a temple dedicated to the older brother of the Japanese sun goddess Amaterasu, god of war, and it was a place of pilgrimage for samurai who often visited and left their weaponry there. It’s easy to see where the inspiration might have come from.

She participated in many battles, but the inciting incident to her career is probably the threat that Ōuchi Yoshitaka constituted for her home island. A war eventually broke out between his clan and the Kōno clan who controlled the island of Ōmishima at the time. Tsuruhime was fifteen at the time and she wasn’t the rebel daughter who wanted to fight: her father had died a year before, and she had been given the position of chief priest. Her stance against the Ōuchi clan was an official one, with her two elder brothers already killed in battle: she proclaimed herself the avatar of a kami, organized the resistance when the Ōuchi samurais raided her island and eventually led an army which drove them back into the sea.

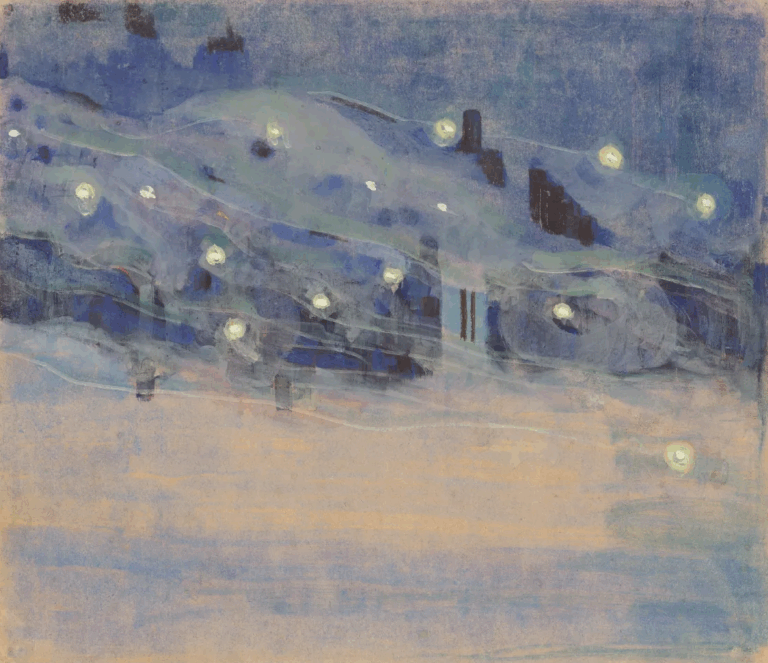

The sea is the main character of the part Benjamin Lacombe decides to illustrate, a story set four months later when the invaders return.

Tsuruhime resumes her role as leader of the resistance once again and throws herself into the cold sea, in an impulsive plan to reach the main ship of the invaders before they can reach the island and raid it again. The water is cold, she’s without her armor, but the sea creatures embrace her and give her strength.

On a side note, I love how the illustration above reverses popular tropes spawning from illustrations such as The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife that Lacombe must know very well. If there’s any eroticism in the picture, Tsuruhime has a definitely active role.

She eventually reaches the ship, where an Ōuchi general, Ohara Takakoto, is drinking with his men. The maiden challenges him in a duel and eventually beheads him. Lacombe decides to illustrate the metaphorical general as an actual one.

After this victory, Tsuruhime goes back to her island and reunites with her army.

After the duel, it’s said the young warrior goes to rest and has a dream: she dreams of peace, at last, but a peace she can only reach by walking into the ocean, drowning herself and communing perpetually with the sea creatures who dwell in there. Some narrators justify her suicide with grief for the death of her betrothed Yasunari Ochi, but I prefer this version better.

Tomoe Gozen (late XII Century)

The first proper room is dedicated to Tomoe Gozen, however, who has also a panel with illustrations by the end of the itinerary. I talked about her a while ago in the second of my three pieces on the Heike Monogatari, where she features as one of the most prominent characters.

Her room revolves around a part of her story as told in Chapter 9 of the traditional ensemble for the Heike Monogatari: her lord is trying to flee from a lost battle, alongside her and his foster brother, but his horse gets stuck in the mud of a paddy field, the enemy’s archers catch up with them and the lord is struck to death.

“Quickly now,” Lord Kiso said to Tomoe. “You are a woman, so be off with you; go wherever you please. I intend to die in battle, or kill myself if I am wounded. It would be unseemly to let people say, ‘Lord Kiso kept a woman with him during his last battle.’

Needless to say, she doesn’t take it well.

She initiates a flight, surrounded by the hissing of arrows, but ultimately can’t stand leaving her lord. She turns around and reaches him, in time to see enemies beheading him and celebrate with his head on a pike. She disembowels one enemy and rips the head off another, recomposes the body and disappears.

Miyagino and Shinobu: the Avenging Sisters

The room is divided in two, as this is the story of two women: one, Miyagino, works as a geisha; the other, her younger sister Shinobu, a farmer. Their story comes from different sources:

- the Katakiuchi Ganryūjima (“Revenge of Ganryūjima”), now lost;

- the Gotaiheiki Shiroishi Banashi (“The Tale of Shiroishi and the Taihei Chronicles”), also lost;

- the play Katakiuchi Noriai-banashi, literally “A Medley of Tales of Revenge”, written by Sakurada Jisuke, which combines the previous two and premiered in 1794.

It’s mostly famous through illustrations, though, particularly the ones by Tōshūsai Sharaku (1794 – 1795).

One of the two sisters, Miyagino, escaped a life of poverty and works as a geisha, she has every comfort and would never go back to the fields even if that meant abandoning her father and her beloved sister Shinobu. One day, however, she feels a piercing pain as she’s dressing up for work, and she immediately knows their father is dead.

A few days later, her sister shows up at her door and tells her that he was killed by a samurai. She’s unable to feel anything: she left that life and longly hated their father for pursuing that life of hardships and sacrifices, which drove their mother to her grave. The two sisters part ways again.

A few days later, however, Miyagino is at the door of Shinobu, without her geisha makeup, and she’s talking about avenging their father. She conducts a summoning ritual and they learn a name: Shiga.

The two girls catch up with the murderer, but none of them is trained in wielding weapons: though they try to catch him by surprise, they would succumb to his strength. The samurai has killed many people, though, and their spirits rise to help the two sisters: the samurai is beheaded, and justice is served.

Yamamoto Yaeko (1845 – 1932)

The third room in the exhibition steps out of myth and into history: it’s focused on Niijima Yae, also known as Yamamoto Yae or Yamamoto Yaeko, a skilled gunwoman who fought during the Boshin War and earned the nickname “Nightingale of Japan”. She was the first woman outside of Imperial House to be decorated for her services to the country. She was also a teacher and a scholar, and served as a nurse during both the Russo-Japanese War and Sino-Japanese War.

Her room is introduced by a still life of rifles and smoke (the smoke it’s odourless, but it’s hilarious hearing people complaining about the smell). This alludes to her battle defending the Aizuwakamatsu Castle wielding a Spencer carbine.

The main installation however is a luxurious set of lanterns dangling in a golden mirrored box.

The Ōgama Toad

The long side of the exhibition, at the left of the three main rooms, is dedicated to the Ōgama Toad, a spear-wielding creature who breathes rainbow. It’s a character from the Tōsanjin Yawa, “Night Stories of Tōsanjin”, a book of yōkai illustrated by Takehara Shunsensai and published about 1841.

It’s said that they have the ability to change their forms and disguise themselves as humans, and they originate from a regular toad after it turns 100 years old.

Toads are connected to another powerful figure, Takiyasha Hime, literally the “waterfall demon princess”. She was a sorceress who raised an army of these yōkai in an attempt to conquer Japan. You can read a part of her story here.

Objects in the Exhibition

Legendary and historical figures aren’t the only things featured in the exhibition: every prop you can interact with has a small label desperately trying to educate the selfie army.ù

Kazaguruma: the pinwheel

Often used by children or as a decoration during the traditional celebrations, it’s said it was invented in East Asia and is possibly one of the oldest figures in origami.

The kazaguruma is also an uncommon opening in the game of shogi.

Senbazuru: the cranes

It’s hard to forget this if you ever read Thousand Cranes by Yasunari Kawabata or Eleanor Coerr‘s classic Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes: the legend says that a person who folds one thousand paper cranes will be granted a wish, however impossible that is. It’s usually a vow performed as the last resort to cure a terminal illness.

The custom comes from the belief that cranes are mystical creatures with an extraordinarily long life, easily reaching the significant threshold of 100 years.

Sensu: the fan

A symbol of royalty, the folding fan is a mandatory accessory for the kimono and it differentiates from the round uchiwa fan which is not foldable. It’s a gender-neutral accessory and a symbol of good luck, though it was initially restricted to aristocrats and samurai.

Nobori: the banner

Generally used on the battlefield to identify the different households lining up in the armies, these vertical banners soon filtered into everyday life and started to identify shrines, temples, storefronts and significant buildings.

Yagura: the scaffolding

A construction between a tower and a scaffolding, the yagura was traditionally used for different purposes, from watching towers to stocking arms and ammunition, from surveying towers to observation points for fire prevention.

They also have an entertainment purpose and serve as a stage for drums or flute players.

Next up in the same space we expect a new interactive exhibition on the history of robots, called Robotland, and inspired by a book illustrated by the Italian artist Berta Paramo.

1 Comment

Pingback:Japanese Robotland – Shelidon

Posted at 11:54h, 24 January[…] the charming exhibition on Women Samurai, Tenoha changes tune and theme and goes cybernetic on us: their new effort is called Robotland, and […]