Oshidori

Happy Valentine’s Day! Do you remember when we started, before going down the rabbit hole of the Heike Monogatari? I was taking a look at the Japanese Ghost Tales by Lafcadio Hearn, so today let’s take a look at the second tale of the collection, which is perfect because it’s also tragic and romantic. It’s […]

Happy Valentine’s Day!

Do you remember when we started, before going down the rabbit hole of the Heike Monogatari? I was taking a look at the Japanese Ghost Tales by Lafcadio Hearn, so today let’s take a look at the second tale of the collection, which is perfect because it’s also tragic and romantic. It’s a short one, so I guess I’ll be able to tell it in full.

1. The Story

Once upon a time, a falconer named Sonjo lived in the district of Tamura-no-Go, in the province of Mutsu.

One day he went out to hunt, but couldn’t catch anything and, on his way home, he noticed a pair of mandarin ducks swimming side by side in a river at a place called Akanuma. Mandarin ducks, called oshidori, are the symbol of married love, as we’ll see, and it’s considered bad luck to kill them, but our hunter was very hungry and aimed.

The arrow hit the male, and the female fled into the reeds on the nearby bank and disappeared. Sonjo took the dead duck home and cooked it.

That night he had a sad dream: it seemed to him that a beautiful woman came into the room and, standing by his pillow, began to cry.

She was crying so bitterly that Sonjo felt his heart break as he listened.

Finally, the woman cried out to him:

– Why, oh, why did you kill him? What had he done wrong? In Akanuma we were so happy together….and you killed him! What harm had he ever done to you? Do you realize what you’ve done? What cruel, evil deed you’ve done? You have killed me too because I cannot live without my husband! I came to tell you only this.

Then she began to weep and lament with such bitterness that her weeping penetrated to the very bones of the man to the marrow and, between sobs, she recited the words of this poem:

Hi kurureba Sasoeshi mono wo

Akanuma no Makomo no kure no Hitori-ne zo uki.

I’m told it roughly means: “At dusk I invited him to return to me. Now I’ll sleep alone in the shadows of the Akanuma reeds… -Ah! What unspeakable suffering!”.

And after uttering these verses, he exclaimed:

-Ah! You don’t know, you can’t know what you’ve done! But tomorrow, when you go to Akanuma, you will see it…you will see it….

Thus saying, and crying in despair, she left.

When Sonjo woke up in the morning, this dream was so vivid in his mind that he was greatly troubled by it.

He remembered the words:

-But tomorrow when you go to Akanuma, you will see him…you will see him.

And he finally decided to go there to see if that dream was anything more than a dream.

He went to Akanuma and there, as soon as he reached the river bank, he saw the female oshidori swimming alone.

At that same moment, the bird noticed Sonjo, but instead of fleeing, it swam straight towards him, staring at him in a strange way.

Then it suddenly slashed its body with its beak and died before the hunter’s eyes.

Sonjo shaved his head and became a priest.

2. Illustrations

In the second book illustrated by Benjamin Lacombe and inspired by the tales narrated by Lafcadio Hearn, cover above, the short story is illustrated with a beautiful plate of the two ducks. If you look closer, you’ll see that the reflection of one and the part underwater of the other are skeletons. A beautiful shot of the page in the Spanish edition was published on Twitter by Primera Página, the account of a bookstore in Urueña.

There’s also a beautiful illustration by Shiro Ohara, who did lots of the tales, and you can see it on his Behance page: he decides to take a shot from above and here you see the beautiful dead duck, floating at the centre of a whirlpool of feathers in the water pool, and the despairing hunter with a bowed head and his bow abandoned at his side.

I think it’s awesome.

We also have what I believe to be one of the original illustrations by Lafcadio Hearn himself, with the archer (holding the bow in a rather strange way), the dead duck and the surviving female running to hide in the reeds of the riverbank.

3. The Ducks

Common motives and symbols at a traditional wedding in China, ducks are a symbol of fidelity, love and particularly of conjugal love, as they are believed to be monogamous and extremely loyal to their partner. This is biologically not accurate, as they do not form a bond for life but they roll with what is known as seasonal monogamy. This is true for all wild ducks, while domestic ducks practice polygamy without any care in the world.

You can see a kimono pattern with ducks, for instance, at this address.

While the Japanese refer to a duck as oshidori, in China they are known as yuanyang and the term comes to informally indicate an unlikely couple, because the two sexes are rather different: the female has dull brown and grey feathers, while the male has the typical bright plumage with splashes of red.

Being such a beloved symbol of love, ducks are a recurrent theme for painting and prints, especially in couples.

Ōkyo Maruyama did this beautiful one around 1750, it’s titled Secchu matsu ni Oshidori which means “Snow-covered Pine tree and Mandarin ducks” and you can find a copy on sale here, if you have $ 119.00 to spare (plus another $ 100 of shipping if you’re outside the US).

At the Toledo Museum of Art, you can find a similar one by Ohara Shoson, created around 1935. On the museum website, another tale is told:

A Japanese folktale tells of a pair of ducks separated when a lord takes the drake to his palace to show off its beautiful plumage. The bird almost dies from grief at being taken from his mate, but two servants bravely conspire to reunite the couple.

If you happen to be at the British Museum, or if you settle to browse their excellent online archive, you’ll find ducks of all shapes and sizes. One of my favourite artworks has to be this by Tsukioka Kogyo painted around 1910 because he just couldn’t seem to accept the fact that the female’s plumage really sucks that much.

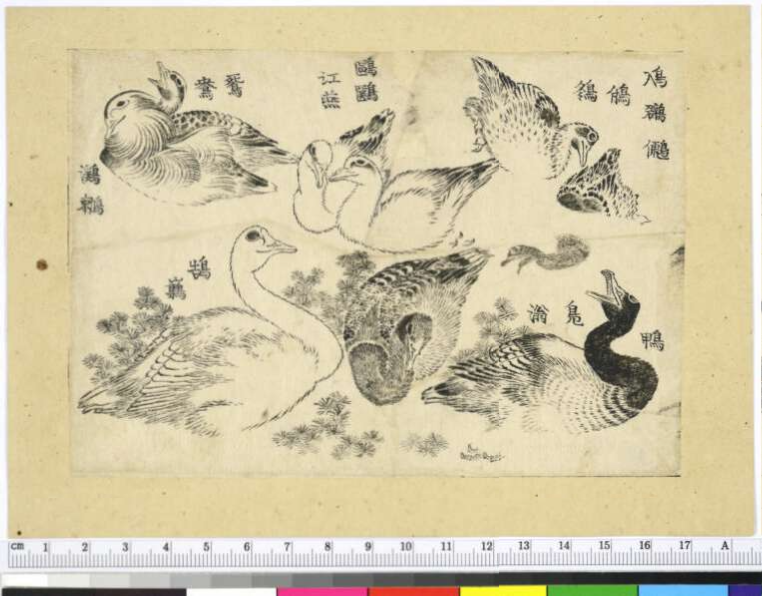

If you want something classical, yes, Hokusai did a couple too: the British Museum has this amazing black and white preparatory sketch done between the 1820s and the 1840s. The inscription translates as:

little grebe duck swan mandarin duck, mandarin duck seagull, reseate tern.

The commentary is awesome: read it up.

This time, however, I think Hiroshige has the upper hand: he gives us this amazing print of a single duck swimming through the reeds and we can imagine it’s the mourning newly-widowed duck of the tale.

Another beautiful scroll at the British Museum is this one, by Murata Sohaku, from the Tenpo era.

If I have to pick a favourite duck, however, it would be this one by Kono Bairei.

3.1. Representations of Theater

If you wish to see how big ducks were, you should as usual look through theatre-related material. The Boston Museum of Fire Arts, for instance, has this depiction of actors Arashi Sangorô II and Segawa Kikunojô III as Mandarin Ducks, done by Katsukawa Shunsho in 1775. See how ducky they look.

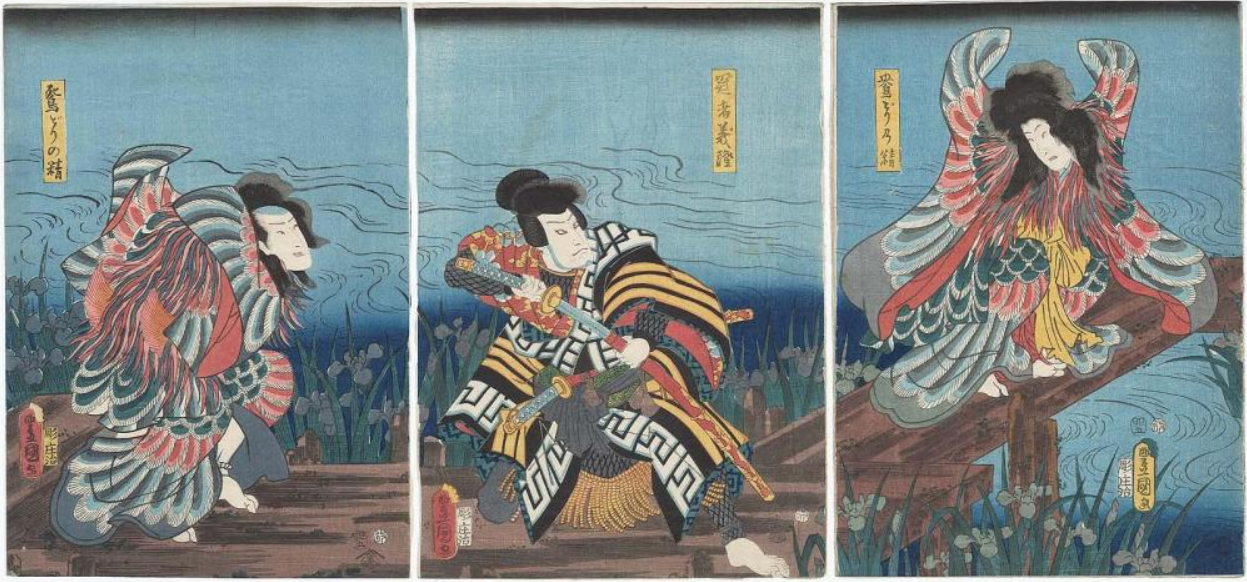

The same Museum of Fine Arts has a beautiful triptych of actors Bandô Takesaburô I as the Spirit of a Mandarin Duck, Bandô Hikosaburô IV as Kanja Yoshitaka, and Nakamura Fukusuke I as the Spirit of another Mandarin Duck. The scene is taken from the play Sanpukutsui Kabuki no Irodori (Il colore della triade contro Kabuki) and the scene is a famous “Dance of the Mandarin Ducks”. The scene is by Utagawa Kunisada I (1786–1864).

3.2. Objects

If you’re less into pictures and more into objects, of course ducks were represented also in netsuke, the miniature sculptures in wood or ivory used as accessories for instance in clothing. My favourites are these two in ivory, made by Ohara Mitsuhiro.

Not into netsuke? Try and take a look at this bamboo case, measuring just 8 x 5 x 2 cm and dating back to the Edo period and on display at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

The description of the object reads:

Black lacquer ground variously sprinkled with hirame verging on nashiji and kinpun; decoration in gold, silver and colored togidashi-e, hiramaki-e and takamaki-e with gold kirikane; interior gold fundame.

It’s a single duck, I know, but it’s awesome nonetheless.

Another beautiful one is here.

Looking for something more abstract? This sword minder from the Edo period with two ducks swimming around is simply awesome and you would never say it’s from the late XVIII Century. Details are here.

4. Core of the legend

As said, the ducks here feature as a symbol of love. In this tale, the duck gets killed while in another version, made popular in English by the retelling of Katherine Paterson, the couple is separated by a feudal lord who wants the male in his palace in order to show off his beautiful plumage (I know, I know, I should say “its” because animals are neutral but I can never bring myself to do it).

The duck is miserable, in the beautiful palace and far away from his mate, and slowly starts to die of heartbreak. This is noticed by a samurai and a maid, lovers themselves, see the suffering of the animal and set him free against their lord’s wishes. The lord condemns them to death.

The tale was illustrated in watercolour by Diane and Leo Dillon, who decided to echo the style of traditional Japanese illustrations.

For the original tale, there’s a beautiful shadow play by Thomas Murrey and you can watch it below.

Details are here.

In the Western world, the same role is played by the turtle dove, a symbol of devoted love particularly in tragic situations because of the mourning tone of their mating singing. One of the first occurrences is in the Canticum canticōrum, the Song of Solomon in the Bible, which is a unique example of erotic poetry within the sacred texts. At 2:14, the poet calls to his love:

O my dove,

in the clefts of the rock,

in the crannies of the cliff,

let me see your face,

let me hear your voice,

for your voice is sweet,

and your face is lovely.

In William Shakespeare‘s poem The Phoenix and the Turtle, we find the same narrative trick, but it’s far less cheerful, as it’s a metaphysical poem about the death of ideal love. The turtle in the title is the turtle dove, and it’s the male of the poem, whereas the phoenix is the female.

Whereupon it made this threne

To the phoenix and the dove,

Co-supremes and stars of love,

As chorus to their tragic scene.