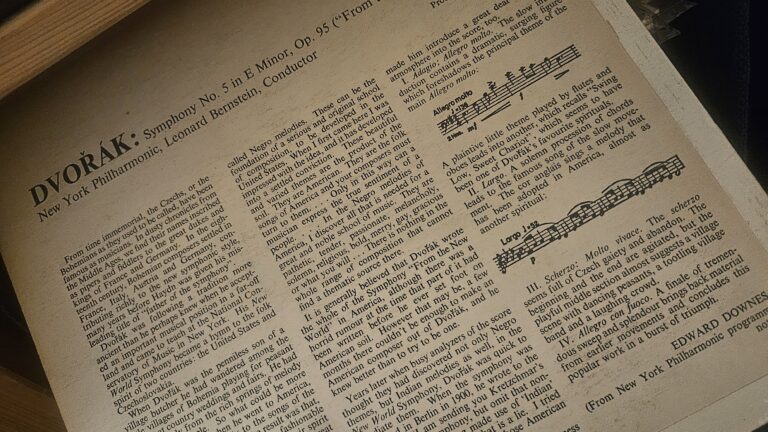

Last week we saw one of the stories narrated by Lafcadio Hearn: the story of the earless minstrel. If you recall, the minstrel found himself telling the epic story of a family downfall to the ghostly court of the dead of that very same family. The story is the Heike Monogatari and I promised you we would take a proper look at that, so here we are.

The Heike Monogatari is a work of epics, written before 1330, considered to be one of the great classics of Medieval Japanese literature, and tells the tale of the struggle between two rival clans: the Taira (平氏), who gives the title to the tale because of the Chinese reading of the kanji 平, and the Minamoto (源), also called the Genji (源氏), or less frequently, the Genke (源家), which is made of former members of the Imperial family, demoted to nobility in order to be excluded from the line of succession. The Taira and the Minamoto fought for the control of Japan by the end of the XXII Century, in what is known as the Genpei War (1180–1185).

The first English translation of the account was done by Arthur Lindsay Sadler between 1918 and 1921, as part of his effort to bridge the gap between East and West. English-born, he was a professor of Oriental Studies at the University of Sydney, he worked in Japan as a teacher and was a prominent member of the Asiatic Society of Japan. For the complete translation, however, we’ll have to wait till 1975, which basically is the day before yesterday. It gives you an idea of how much it remains to be done in order to understand our neighbours with the Rising Sun Flag.

For a complete Western-language bibliography of the Tale of Heike, I suggest you refer to this resource.

I did not read the complete translation, but only excerpts, so you’ll have to correct me if I get something wrong, but if you like accounts of war with vibrant and tragic characters, if you like epic battles and extraordinary military events, this is the tale for you. There’s also a retelling in prose by Eiji Yoshikawa, called New Tale of the Heike, which was published in 1950.

Aas it happens for many epic tales, the Heike Monogatari cannot be traced back to a single author and its merit is mostly to be traced back to wandering storytellers like the biwa hōshi, the lute-playing monks our story is mostly concerned about. As such, the epic is marked by duality. Japanese and Chinese intertwine in the prose, which makes it difficult to read and translate even if you know Japanese, and there are traces of two main influences: a Buddhist one, with an accent on the volatility of material things and the exaltation of themes like duty and fate, and the samurai one, which results in an exaltation of martial valour. In both instances, the dramatic aestheticisation of death makes it a wonderful reading for anyone who’s into gothic literature as a broad genre.

The sound of the Gion Shōja bells echoes the impermanence of all things; the color of the sāla flowers reveals the truth that the prosperous must decline. The proud do not endure, they are like a dream on a spring night; the mighty fall at last, they are as dust before the wind.

The Story is divided into 12 chapters and a secret one. Let’s see what is it about.

1. Chapter 1

The famous introduction features the bells of Gion Shōja, one of the most famous Buddhist monasteries in India, as a symbol of volatility, impermanence, and as a warning on how even the mightiest might eventually fall. It tells the story of how the Taira clan ascended at court, starting from Taira no Tadamori who was the first to gain access around 1131.

Taira no Tadamori was governor of the provinces of Harima, Ise, and Bizen, at the time, and he’s credited to be the first samurai to serve directly the Emperor at court, without the intermediate action of a minister or a noble patron. As such, we set the tale as one of military pride: Tadamori was the sword of the Emperor and waged wars against the pirates of San’yōdō and Nankaidō, but also pursued his own ambition, waging battles against the sōhei, the Buddhist warrior monks of Nara and of Mount Hiei.

His merits were not just military ones: he’s also credited with the construction of the longest wooden building in the world, the Sanjūsangen-dō, within the Rengeō-in temple in Kyoto. After this architectural endeavour, he was granted the additional governorship of Tajima.

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, “Kurō Hangan Minamoto Yoshitsune and Musashibō Benkei under a cherry tree” (1885)

After his death, in 1159, his place at court is taken up by his son, Taira no Kiyomori. Emperor Go-Shirakawa is having his troubles, at the time, with two parallel rebellions: the Hōgen rebellion (1156), a succession war started by the Fujiwara clan, and the Heiji rebellion (1159) which prompted from the first. Kiyomori proves a key resource in suppressing both, thus strengthening furtherly the position of his clan at court.

Kiyomori’s mother, Gion no Nyogo, was a palace servant and it’s speculated that Kiyomori was the illegitimate son of the Emperor but, regardless of the additional favour he might have seen him granted at court, his military valour allowed him to establish the first administrative government led by samurais in the history of Japan. Kiyomori’s daughter becomes the Emperor’s wife and there doesn’t seem to be any limit to their power, but Kiyomori grows arrogant and self-conceited.

One of the most beloved tales of this section, introducing the character of Kiyomori and making sure we don’t like him, is the tragic story of the dancer Giō, on which I can only recommend a beautiful study by Roberta Strippoli, called Dancer, Nun, Ghost, Goddess: The Legend of Giō and Hotoke in Japanese Literature, Theater, Visual Arts, and Cultural Heritage. The hardback edition is unfortunately rather pricey, and so is the eBook, but it’s totally worth it.

Dancer, Nun, Ghost, Goddess explores the story of the dancers Giō

and Hotoke, which first appeared in the fourteenth-century

narrative Tale of the Heike. The story of the two love rivals is one of

loss, female solidarity, and Buddhist salvation. Since its first

appearance, it has inspired a stream of fiction, theatrical plays, and

visual art works. These heroines have become the subjects of

lavishly illustrated hand scrolls, ghosts on the noh stage, and

Buddhist and Shinto goddesses. Physical monuments have been

built to honor their memories; they are emblems of local pride and

centerpieces ofshared identity. Two beloved characters in the

Japanese literary imagination, Giō and Hotoke are also models that

have instructed generations of women on how to survive in a maledominated world.

I’m lucky enough to own the book, so I’ll talk about this character a bit more next week, but the story in itself is brief: Giō is a dancer at court and, during a show, she’s seized and raped by Kiyomori. The warrior takes her up as his lover, completely on a whim, and is equally quick to discard her when the youngest Hotoke, equally unwilling, comes along. Giō is therefore forced to retire and become a nun, alongside her mother and sisters.

Eventually, Hotoke becomes a nun as well, and the two women live the rest of their days in sisterhood.

Toyohara Chikanobu, Kiyomori seizes the young dancer Hotoke, under the eyes of his former favourite Gio (1884)

Angered by the Taira’s arrogance, a few contrary noblemen meet up at the villa of the administrator Shunkan: they are Major Counselor Fujiwara no Narichika, his son Fujiwara no Naritsune, Buddhist monk Saikō of the Fujiwara clan, a Genji from Settsu province called Tada no Kurando Yukitsuna and the retired Emperor Go-Shirakawa himself. The gathering is known as Shishigatani incident and took place in 1177, but the conspiracy is postponed and eventually discovered, as Tada Yukitsuna acts as was a spy for Kiyomori. The other perpetrators are put to death and the Taira clan, under Kiyomori, grows more powerful than ever.

The chapter closes with the great fire of May 27th, 1177 as an example of karma: the corrupted rule of the Taira clan leader causes the destruction of the Imperial Palace in Kyoto. The tragedy is known as The Great Fire of Angen, being the largest of its Era, and it allegedly inspired the notion of impermanence in the production of famed musician and poet Kamo no Chōmei. Kujo Kanezane, a nobleman of the time, records the event in his Gyokuyo, an autobiographical account of his life. Accurate accounts of the damages can be found on this page.

Around 10 p.m., a fire broke out in the northern direction. I heard that the fire started at Higuchi-Tominokoji. A servant reported that “the fire wasn’t yet controlled, and a great many houses in the Capital had burnt down. The fire is approaching the Kan-in Palace.”

I was awakened and looked outside. I saw that the flames blazed even more fiercely and sparks were blown northwestward. Due to my sickness, I remained home and had a servant go to assess the situation. After returning, he reported that “the Kan-in Palace escaped the spread of fire. However the force of the fire is increasing, and the palace is under threat. Therefore, the Emperor has moved to (Fujiwara) Kunitsuna’s residence* at Ogimachi-Higashinotoin. The Empress also moved”.

I should investigate the detailed situation later on. The sudden departure of the Emperor amid the throes of agitated people must have been caused by a devil. People echo similar opinions.

After the fire, it is believed that the retired Emperor Go-Shirakawa ordered the production of a grand handscroll, the Ban Dainagon Ekotoba (“The Tale of Great Minister Ban”) in order to placate the angry spirit of Ban no Yoshio, the god of Pestilence, who originated from the deceased minister himself. The whole story revolves around the Ōtenmon conspiracy involving Tomo no Yoshio, who was falsely accused of burning down the Otemmon gate and, after being put to death, thus became the angry spirit we know.

A portion of the Ban Dainagon Ekotoba, the scroll commissioned to pacify the angry spirits after the 1177 fire.

2. Chapter 2

The Chapter opens with another conflict: the retired Emperor is siding with his relative, the monk Saikō, in plotting against other warrior monks of Enryaku-ji on Mount Hiei. Taira no Kiyomori is however informed of the plot and grows angry at the retired Emperor not really being retired, since technically he abdicated in order to become a Buddhist priest under the name of Gyōshin. The monk Saikō is executed and Kiyomori prepares to arrest the former Emperor, but this is where we meet Taira no Shigemori, the eldest virtuous son of Kiyomori. He warns his father against this action, reminding him of Confucian values such as loyalty, and enters our tale as the first really positive character on the Taira side. Major Counselor Fujiwara no Narichika is however exiled to an island where he’s executed in the most gruesome way, and other conspirators are exiled to Kikaijima.

A second fire, however, appears to warn us of the decline of the Taira rule in the eyes of Fate. The Enryaku-ji complex is destroyed and a Buddhist statue goes up in flames at the Zenkō-ji, a grand temple in modern Nagano.

People start to see these accidents for what they really are: signs of fucking bad karma.

Meanwhile, in Kikaijima, the exiled conspirators are praying for their return to the Capital. They engrave a thousand wooden cylinders with their names and throw them into the sea, as a propitiatory rite. One of these objects is eventually washed ashore in the Capital and is brought to the family of one of the conspirators, Yasuyori. Once the retired Emperor and Kiyomori receive this news, as you can imagine, they have very different feelings about it.

The Kumano Shrine Museum preserves a handscroll depicting this part of the story from the point of view of the exiled.

3. Chapter 3

Since fires are not working, the Taira’s bad karma eventually catches up a form their leader understands: Taira no Tokuko, Kiyomori’s daughter is the Empress consort of Emperor Takakura and is pregnant with their first-born, but she’s taken by a mysterious sickness. Believing this sickness to be originated from the curses of those who were exiled by Kiyomori, the samurai resolves to have them pardoned and Fujiwara no Narichika’s son Naritsune and Yasuyori are pardoned. The only one to stay on the Kikai Island is Shunkan, for punishment to have offered his villa for the treacherous gathering. He’s not happy about it. He’s not happy at all.

Yoshitoki, “Shunkan Watching Enviously from Kikai Island as Yasuyori Returns to the Capitol after Being Unexpectedly Pardoned” (1886)

Kiyomori’s daughter, Taira no Tokuko, thus gives birth to a healthy son, the future Emperor Antoku, who will become the 81st emperor of Japan and will rule for five years only, between 1180 and 1185 when he will die at only seven years of age.

Meanwhile, a loyal servant named Ariō is finally able to journey to the island where his master Shunkan is exiled. Bearing the news of the death of Shunkan’s whole family, the servant can only see his master withering away, heartbroken. His death is seen as another bad omen, particularly considering the fact that it’s followed by a whirlwind on the capital.

Kiyomori’s only virtuous son, Taira no Shigemori, finally decides to go and seek advice: he ventures on a pilgrimage through the Kumano Kodō, the ancient routes of penitence and sacrifice, and he asks for a quick death should his family fall in ruin. The answer is swift: he falls ill and dies in a matter of days. Without Shigemori, his father has no good advice left: he’s on the verge of going to war with the retired emperor Go-Shirakawa and marches on Kyoto with his soldiers: he exiles the remaining courtiers who were loyal to the previous emperor, including Regent Fujiwara no Motofusa, and imprisons Go-Shirakawa inside the ruined Seinan palace. It’s 1779.

4. Chapter 4

After this coupe, Emperor Takakura is forced to retire and the son of Taira no Tokuko, Kiyomori’s daughter, rises to the throne. He’s only three years old.

This is the last straw: the court poet Minamoto no Yorimasa goes to the second son of Go-Shirakawa, Minamoto no Mochimitsu also known as Prince Mochihito, and persuades him that it’s finally time for the Minamoto to take up arms against the Taira clan in order for him to become Emperor. Kiyomori’s son Taira no Munemori, young and arrogant, provides the incident for starting the war after a public scene in which he humiliates the poet’s son, taking away his horse and starting to call it by his master’s name out of spite.

Taira no Kiyomori, however, once again discovers the plot against his own clan and prompts the arrest of all conspirators: Prince Mochihito flees to the temple of Miidera, a Buddhist temple at the foot of Mount Hiei, but this isn’t enough to stop the Taira. A battle is fought between the monks of Miidera and the Taira forces, at the bridge over the Uji River, but the monks are defeated and the Taira clan raids the temple in search of the conspirators. This battle is considered the beginning of the Genpei War.

Yorimasa, the court poet, flees to the Byōdōin temple where he commits suicide, and Prince Mochihito is killed on his way to seek the aid of his allies in Kōfuku-ji, one of the Seven Great Temples of the city of Nara.

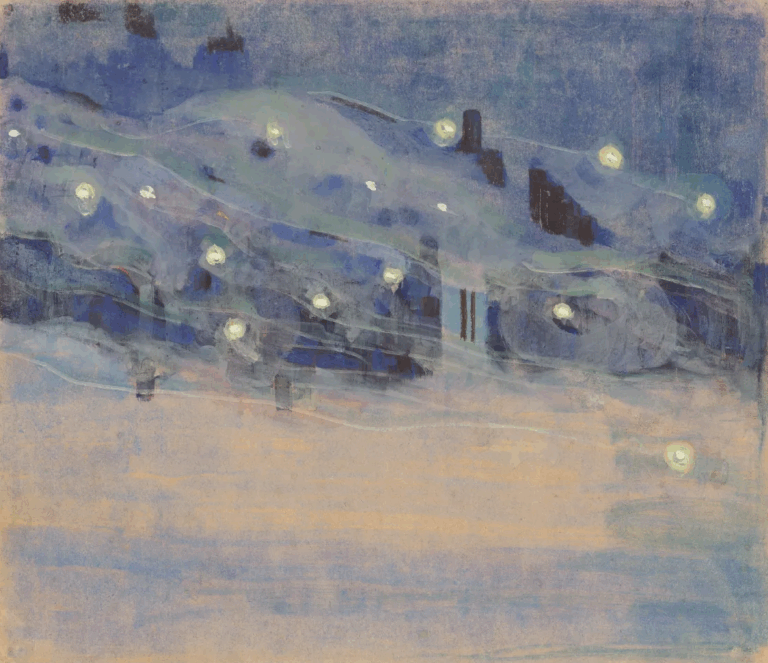

One of the Prince’s sons is forced to become a monk. His other son flees north to join the Minamoto forces and Kiyomori, completely out of control at this point, gives orders to burn the Miidera temple. Many other temples are burned in search for the other conspirators and people watch horrified as the fires of the burning temples light the sky.

5. Chapter 5

Kiyomori moves the capital, the young emperor and the court from Kyoto to a more secure place: his stronghold Fukuhara-kyō. The court however doesn’t appreciate the transfer, particularly the wet weather and the secluded place of the new capital and the Taira leader Kiyomori is visited by the omen of bad dreams, up to the point where he’s hallucinating skulls in his garden.

This makes for some of the most beautiful illustrations of the saga, like this one by Yoshitoshi…

…or this one by Hiroshige that you can see beautifully described in this blog post.

At this point in the story, we meet another crucial character: a monk named Mongaku who had already crossed paths with Emperor Go-Shirakawa and was exiled after the court’s refusal to pay him tributes. Mongaku has strange powers and convinces Minamoto no Yoritomo to take up arms against the Taira. This time, Kiyomori’s forces are afraid to be defeated and they retreat in shame, forcing him to face the discontent of the court and move the capital back to Kyoto. His fall has started.

The Taira forces lay siege to Nara and burn their temples, while monks of the Kōfukuji temple revolted against the wicked rule of the Taira and killed the messengers sent to ask for their allegiance.

What will happen next?

We’ll see it next week.

No Comments