People over at Twitter called for Folklore of our local places, so I thought I’d unearth some of my favourite Italian folk tales.

1. We invented Cinderella

I’m sure all of you are familiar with Cinderella and similar tales, but few know that the oldest tale of that sort comes from Italy and particularly it’s one included in the Cunto de li Cunti (Tale of Tales) collected and retold by Giambattista Basile. There’s a movie with Salma Hayek that brilliantly conveys the atmosphere of the tales: it’s a mix of marvellous, strange and horrific, with people being skinned alive, fleas being skinned while dead, curses, enchantments, weird stuff. It is sometimes known as The Pentameron. The text was properly translated in English by John Edward Taylor first, in 1847, and then by no other than Sir Richard Francis Burton in 1893. It’s not in Italian, it’s in an ancient version of the vernacular language of Naples, so it was also translated in Italian around 1925 by Benedetto Croce. So yeah, it was translated in English before it was translated in Italian. And, trust me, this was not because everyone could understand it. I’m from Milan and I can’t understand it. My significant otter is from around the place it was written and he has trouble understanding it. It’s tough stuff.

The Brothers Grimm knew the collection and talked about it in their third edition of their Collected Fairy Tales. They knew very well you could find in there the early versions of stuff that is today known as Cinderella, Hansel and Gretel, The Sleeping Beauty and Rapunzel.

The Tale of Tales is a frame story, like the Decameron and The 1001 Nights: a cursed Princess who cannot laugh is entertained by her father who plays pranks on his subjects in order to break her melancholy but, when he finally succeeds, she laughs at the expenses of the wrong person, an old woman who launches a new curse and binds her to marry the prince of Round-Field, who is fast asleep and can only be woken by a jug of tears filled in no more than three days. Helped by fairies, she’s almost successful. In fact, she fails by one drop and falls asleep herself, but the jug is stolen by a Moorish slave who spills the last drop and unjustly claims the prince.

Flash forward: the usurper princess is now pregnant and demands that her husband tells her stories or she would crush their unborn child in her womb. The prince hires ten storytellers to keep her entertained and one of them is the cursed Princess herself, awaken from her slumber. Within her tales, she reveals the usurper’s treachery and the princess is buried, pregnant, up to her neck and left there to die. And they all lived happily ever after.

Yup.

We don’t mess around,

even in folk tales.

This is the index of stories:

- On the First Day:

- “The Tale of the Ogre”

- “The Myrtle”

- “Peruonto”;

- “Vardiello”

- “The Flea”, which you could see in the 2015 movie;

- “Cenerentola”, which is of course a variant of Cinderella;

- “The Merchant”

- “Goat-Face”

- “The Enchanted Doe”

- “The Flayed Old Lady”, also in the 2015 movie.

- On the Second Day:

- “Parsley”, which is a variant of Rapunzel;

- “Green Meadow”;

- “Violet”;

- “Pippo”, which is a variant of Puss In Boots (fun fact, “Pippo” later came to be the Italian name for Disney’s Goofy);

- “The Snake”

- “The She-Bear”;

- “The Dove”;

- “The Young Slave”, which is a variant of Snow White;

- “The Padlock”;

- “The Buddy”.

- On the Third Day:

- “Cannetella”

- “Penta of the Chopped-off Hands”, the girl with no hands being another trope in folklore;

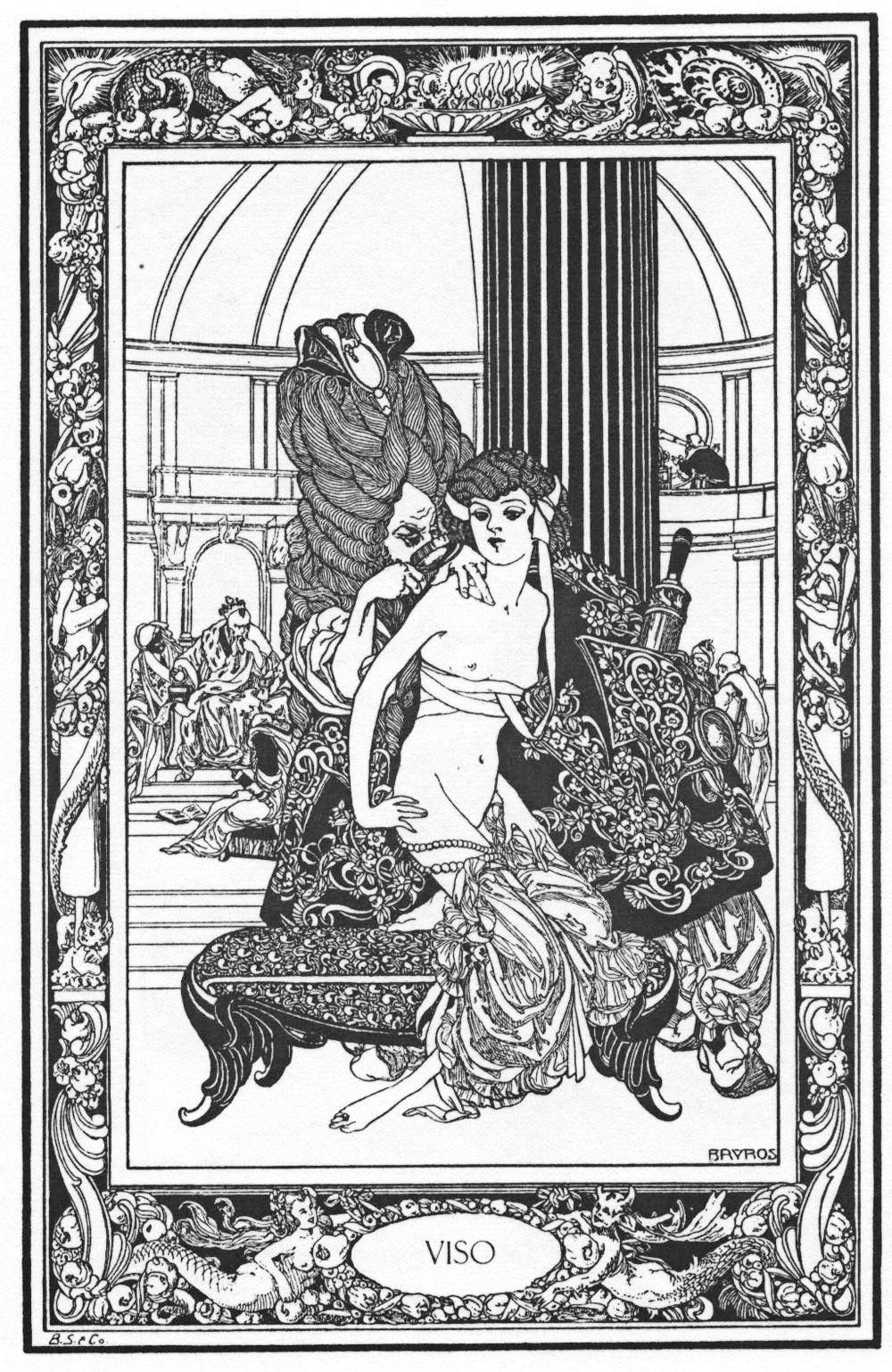

- “Face”;

- “Sapia Liccarda”;

- “The Cockroach, the Mouse, and the Cricket”;

- “The Garlic Patch”;

- “Corvetto”;

- “The Booby”;

- “Rosella”;

- “The Three Fairies”, which is a variant of Frau Holle.

- On the Fourth Day:

- “The Stone in the Cock’s Head”;

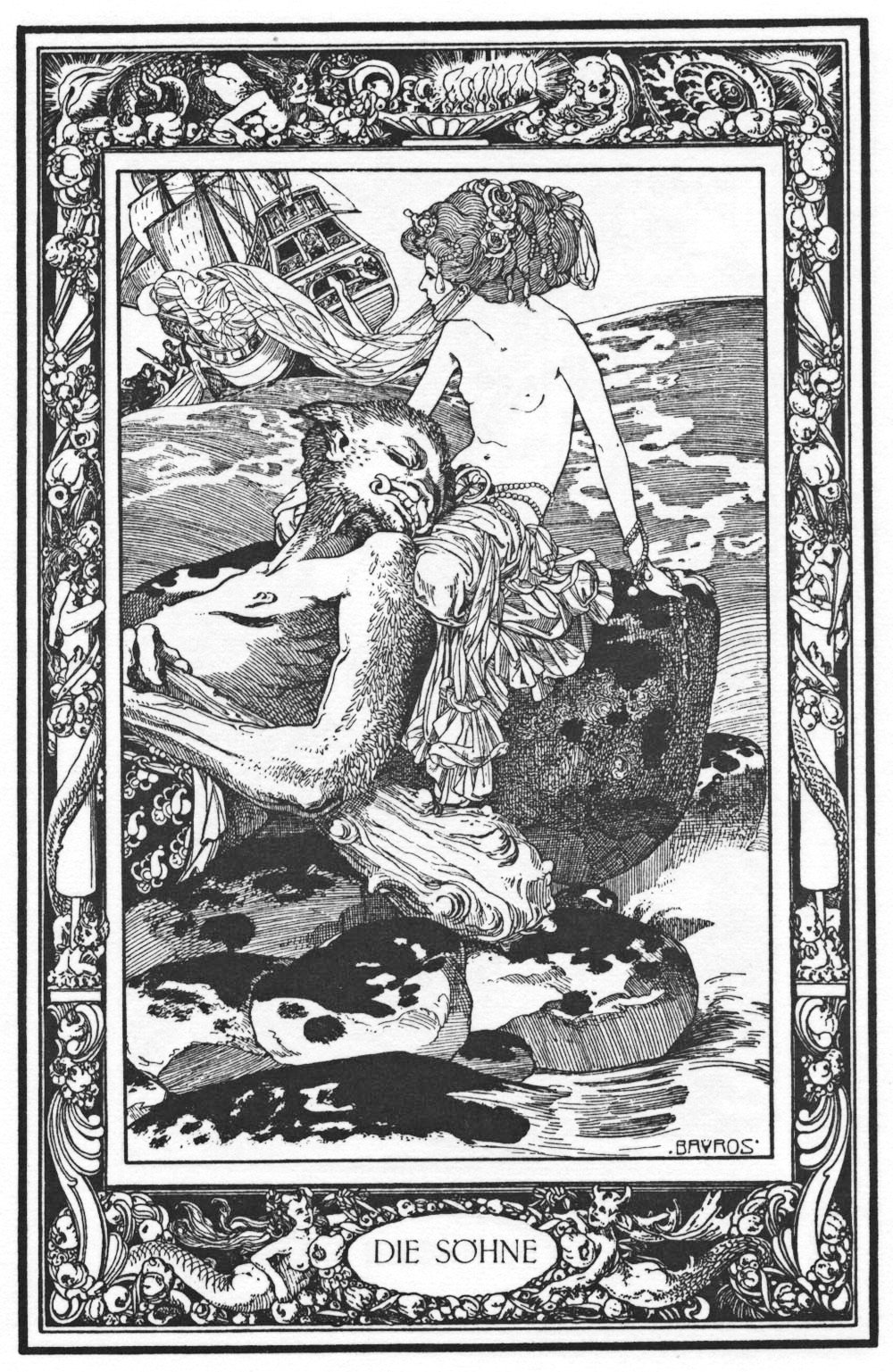

- “The Two Brothers”;

- “The Three Enchanted Princes”;

- “The Seven Little Pork Rinds”;

- “The Dragon”;

- “The Three Crowns”;

- “The Two Cakes”;

- “The Seven Doves”, a variant of The Seven Ravens;

- “The Raven”;

- “Pride Punished”.

- On the Fifth and Final Day:

- “The Goose”;

- “The Months”;

- “Pintosmalto”;

- “The Golden Root”;

- “Sun, Moon, and Talia”, which has lots of themes of both Snow White and The Sleeping Beauty;

- “Sapia”;

- “The Five Sons”;

- “Nennillo and Nennella”;

- “The Three Citrons”.

The first editions were illustrated by your affectionate usuals: George Cruikshank worked on the 1847 translation by John Edward Taylor, and six full-page drawings by Michael Ayrton accompanied the new translation by Sir Richard Burton (you can see a copy here).

But there are also some other illustrations that are worth mentioning: Franz von Bayros did ten amazing plates for a 1909 edition and they are one more beautiful than the other. My favourite has to be this one.

Isn’t it awesome?

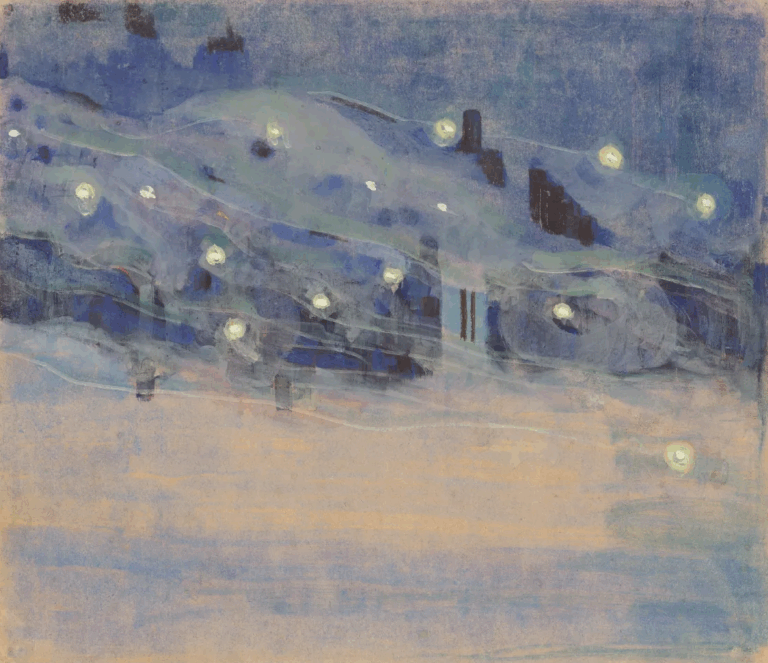

It’s the 1911 English edition, however, that has the real gems, as this MacMillan edition, curated and translated by one E.F. Strange, was illustrated by no other than Warwick Goble. They are one more beautiful than the other and it’s hard to pick one, but if I had to, it would be this.

Anyway, this is not what I wanted to talk to you about, because these are tales from Naples and I’m not from Naples.

2. The Marjoram Pot

When I did my run of the Winter Tales, I briefly talked about Italo Calvino and his work in collecting folk tales from all across the Country. There is some beautiful stuff in there, but two of those tales are from Milano, my city, so I picked one. It’s called “The Marjoram Pot”. There is also a complete retelling here, so you can forget about me and go there if you want, but I have pictures. In case you’re really curious, here you can find the Italian text with a vernacular version in front (yes, I can understand both, but it gives you a clear idea of the difference there is between Italian and a vernacular language: they are two different languages). The original 1956 edition is illustrated by Giulio Bollati in medieval style. I published something on my Instagram profile a few months ago.

Wait, what’s marjoram?

It’s a herb heavily used in the kitchen both in Italy and Greece. It was considered the symbol of happiness and it was believed that its leaves had the power to prevent milk from going sour. According to myth, the goddess Afrodite was the first one to harvest this plant and she picked its aroma herself, therefore young maidens in ancient Greece believed that putting some leaves of marjoram under their head at night would induce Morpheus to bring them in a dream the face of their future husband. Marjoram is still used inside drawers, of all aromatic herbs, to bring a gentle scent to undergarments.

Don’t worry, its role in the tale is really marginal.

Once upon a time, there was an apothecary. He was a widower and he had a beautiful daughter whom he called Stella Diana (literally Star Diane). Every day, Stella Diana went out to a teacher in order to learn sewing and her teacher had a beautiful balcony with the most amazing plants and flowers. They were all flourishing, but Stella’s favourite was a pot of marjoram and every day she went out to water it.

Don’t get your hopes up: the tale has nothing to do with Isabela and her pot of Basil.

Her love for the plant, however, might not have been the only reason for her to go out, since in front of the terrace lived a young gentleman and the gentleman started courting her. With, I have to say, very little success. Their courtship is in verses and goes pretty much like this:

Stella Diana, Stella Diana,

how many leaves does your marjoram have?

(in Italian I swear it rhymes)

And she retorts:

Oh handsome noble knight,

How many stars are in the sky?

(or skyght, if you want to make it rhyme)

The stars in the sky cannot be counted.

And she goes:

And my marjoram is not for you.

I think it’s clear that she’s not talking about the plant anymore.

It’s a reversed Romeo and Juliet: instead of using the balcony for courting, they use the balcony to make fun of each other.

The youth is not to be discouraged so easily, however, and he tries a different trick to win her favours: he dresses up as a fisherman and barters a fish for a kiss, only to rub the trick in her face when he talks to her again on the balcony.

Stella Diana gets mad and, of course, concocts a trick of her own. She dresses up with a beautiful precious belt, mounts on a mule and parades up and down the street where the gentleman lives. As soon as he sees the belt, he asks her to sell it to him. She only asks for a little price: that he kisses the mule’s tail.

It must be a really beautiful belt, or again the belt has nothing to do with anything, because the young man complies and kisses the mule’s tail, and off he goes with the precious belt.

And then again they meet on the balcony, and the girl’s trick is added to their questionable poetry exchange.

Another day, another trick: the young gentleman bribes the teacher so that she’ll let him hide under the staircase, and when Stella Diana passes he pulls at her skirt from below. Because we’re all eight years old when we’re in love.

The girl gets scared and the youth makes fun of her, as usual, from the usual balcony.

Another evening, another trick: it’s Stella Diana’s turn to bribe the man’s servant and she shows up in his house, dressed up as Death herself and scaring him enough that he sends her to his aunt, who is old and apparently willing to die (at least according to him).

This is the last drop: the man decides it’s time for the ultimate trick and goes to Stella Diana’s father, asking for her hand in marriage.

This would be a good ending, wouldn’t it?

It certainly would.

But no, we’re fun people (do you remember the Tale of Tales’ happy ending?)

The wedding day approaches and Stella Diana is fearful that her future husband will want revenge for all the tricks and pranks she played. She creates a lifesize doll made of dough and dresses it up in her nightgown. In place of her heart, she puts a bladder filled with milk and honey. And, when night falls, she puts it in bed in her place.

The newly-wed husband arrives and seems to be finally happy. “It’s time to get revenge for all your pranks!”, he says, and he unsheathes a knife, digging it into the doll’s heart.

It’s all good and fun until your husband turns into Bluebeard, right?

The bladder ruptures and the mixture of milk and honey spreads all around, ending up also in the husband’s mouth. In tasting how sweet the blood of his wife was, the man repents. “Oh, dear me! How sweet her blood was, and I killed her! What have I done? If only could I have her back!”.

In hearing these words, Stella Diana emerges from her hiding and, instead of killing the asshole, they live happily ever after.

No Comments