An Uncomfortable House

Chapter IV of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland features a new meeting between Alice and the White Rabbit, who’s still worried about being late with the Duchess (a character that’s usually blended with the Queen of Hearts). It’s another famous growing up / shrinking down scene, the one within the White Rabbit’s house, so our guidance […]

Chapter IV of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland features a new meeting between Alice and the White Rabbit, who’s still worried about being late with the Duchess (a character that’s usually blended with the Queen of Hearts). It’s another famous growing up / shrinking down scene, the one within the White Rabbit’s house, so our guidance for illustrations has to be the Alice Big and Small blog. I already used it as reference when we firstly saw Alice drinking from the bottle on the glass table.

There are three or four main moments, in this chapter:

- Alice meeting again the Rabbit and getting asked to go and fetch him a new pair of gloves;

- Alice going through the Rabbit’s house, drinking again from a bottle and growing up again inside the Rabbit’s house;

- Alice reaching out a window in order to find a way to shrink back down.

1. Here goes the Rabbit Again

As usual, Arthur Rackham decides not to give us the satisfaction of illustrating the crucial situation in the chapter, trusting us to imagine it better, and draws a marginal scene, in which the rabbit finds Alice and mistakes her for a certain Mary Ann.

The actual cottage is not often illustrated if not to show Alice’s arms and legs coming out from the windows when she’s all grown up. Charles Robinson provides a good exception with this delightful black and white drawing.

He also gives us a picture of Alice running towards the house and then, instead of showing the scene where an arm is about to come out from the window, decides to stop half a second before, and shows us the exterior window still intact.

Of course the possibility of seeing illustrations of the rabbit’s house is one of the reasons I love browsing illustrations for this chapter: Carroll gives us no description at all, so there’s room for interpretation.

…a neat little house, on the door of which was a bright brass plate with the name “W. RABBIT” engraved upon it.

The funniest one among classical illustrators is, in my opinion, Brinsley LeFanu‘s: he decides to give us a house that’s clearly belonging to the white rabbit. It has ears and spectacles.

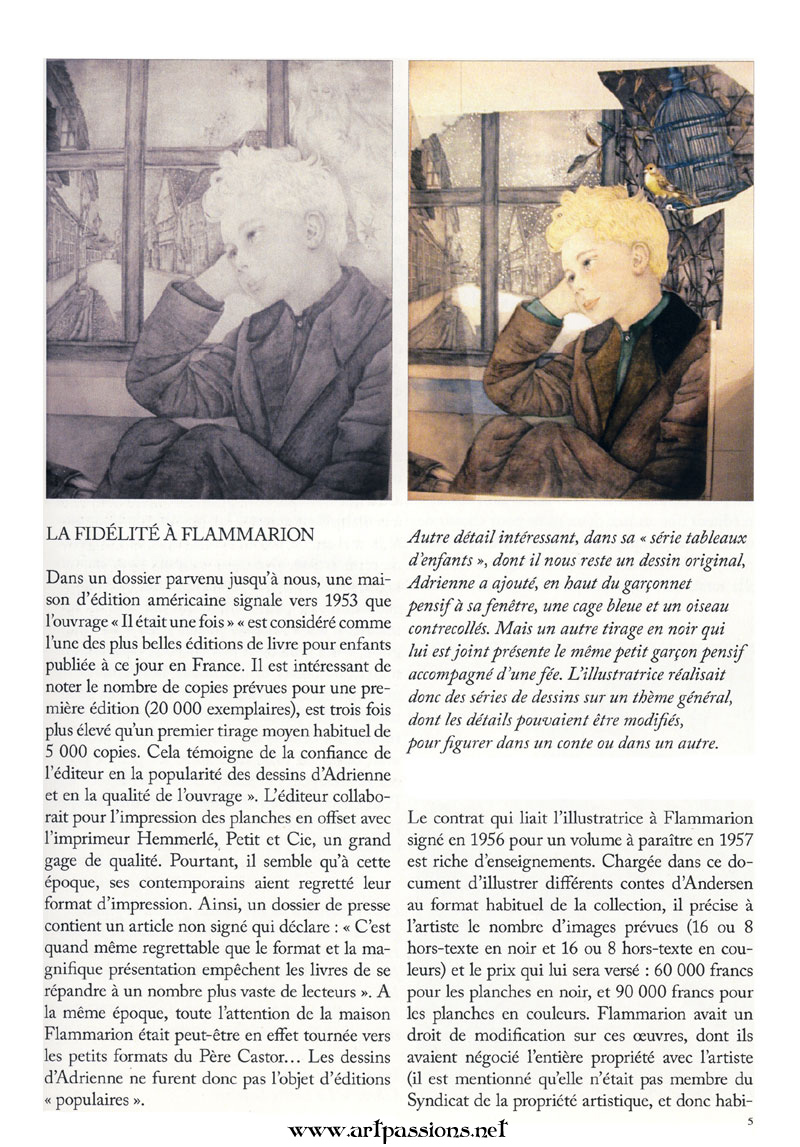

The idea is charming and, oddly enough, not picked up or reinvented by many authors. Adrienne Segur is one of them and I love everything about this artist. There’s a biography here (in Italian) which in turn quotes this source, that you unfortunately have to scavenge for on webarchives. Such is the nature of web browsing in the era where people have moved to fucking Facebook and goddamn Pinterest. The article gave us, in turn, the translation of an article by Irene Autin, but first, let’s see the illustration I’m talking about.

Since the website is no longer on-line, I though I should repost something about Adrienne Segur, so I hope you’ll forgive me for the digression. Her Wikipedia page is disgracefully short.

I was going to the home of Adrienne Segur, who is magical, a fairy. I was welcomed by an imperial cat and brightly colored birds. All the animals in “Il etait une fois” [The Fairy Tale Book — XA] perched in the far corners of the house. What did the fairy say to me? “I go to the land of fairies to avoid myself. The child talks to animals and the animals talk to him, it’s totally natural. My animals talk to me with their eyes, their paws, their snouts.” (Figaro Litteraire, 1952)

«Adrienne Segur was born in Grece, in Athens, on 23 November 1901. She was the daughter of French writer Nicolas Segur (a friend of Anatole France) and the Greek Kakia Anastase Diomede Kyriakos. Adrienne married the Egyptian poet and thinker Mounir Hafez around 1932. It was he who announced that her death had occurred on 11 August 1981 at Plessis-Robinson 133, Avenue de la Resistance. She had by that time retired, and lived officially in Paris in the sixth arrondissement, at 115, rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs. She had stopped drawing a short time before the publication of The Legend of Venise in 1973. Arthritis no longer permitted her to work.

«A clearly elegant woman, even worldly, and probably celebrated for her great beauty, Adrienne Segur married a man more than ten years younger than herself and who “by his personal itinerary had been in contact with noted personalities in the 20th century in the fields of contemporary thought and art, in science, and in spirituality. Assistant to Henry Michaux, Mounir Hafez was friend to Louis Massignon, Henry Corbin, Georges Bataille, Cioran, Blanchot,…” Until 1952, he spent his summers in Paris and his winters in Cairo until 1952.

An additional page on the same website, retrieved through webarchives as well, gives us more information on her style.

«Adrienne Segur made Paris her home until 1950 in a home provided for her by the Flammarion publishing house — ten kilometers south of Blois, by Gervais Forest. There, she was surrounded by animals, just like the heroines in her stories. We can therefore assume that her husband and she did not have a life organized in the conventional manner that was usual for their time. It is important to note that 1936 to 1939, she was the director of the children’s page for the daily Le Figaro. She designed all the illustrations in this section. Then came the War and its troubles. The couple was denounced as “English” and arrested.

«The illustrator, whose eyes were beautiful and limpid, attached great importance to the expression of her characters, where show subtle touch-ups make the final impression Her other-wordly expression inspired the photographer Erwin Blumenfeld, who had taken up residence in Paris after 1936, creating beautiful black and white portraits before the war, in a style half-way between the Harcourt Studios and Surrealism.»

«The style and even the name of Adrienne Segur evolved throughout her strange career, as did her signature. And it was under the name of Adrienne Novel that she did her first illustrations. Without doubt inspired by the artists of her time, she signed the compositions in black and white for Andre Maurois’s The Country of Thirty-Six Thousand Wishes in 1929. She published again, this time in color, during the 1930, The Adventures of Cotonnet [The Adventures of Cotonnet], (her Cotonnet Aviateur est dedicated to the French humanist, Armand Marquiset). She made up the stories, writing in a style that one could consider, in some places, just a little too precious.

«As proof of her long-term interest in fairy tales is a surprising version of The Fairy Tales of Perrault by Adrienne Segur, dating from 1934 and published by Sudel. In an oblong format, text that she herself adapted is illustrated in black on every page, and signed with the monogram A in a square. The work shows another time in her evolution, her compositions, spanning both pages, are graphic and abstract. The features consist of short lines, curves, and dots, evoking the manner of Maggie Salcedo. The talent is evident, the composition extraordinary.»

A fourth page gives us an insight on later works and some examples of her visionary works.

«As an artist, Adrienne Segur had a passion for the story of Alice by Lewis Carroll. In 1947, she published A Little Pig Went to School, a variation, both literary and artistic, on Carroll’s theme. In her Alice in Wonderland illustrations, published in 1949, the face of the little girl has not yet become the smooth regular features we know in her later angelique heroines. But one finds the mouth in color, the small nose, and the round eyes with the long eyelashes of girls’ rosy cheeks from A Little Pig Went to School. The wonderful tints used successfully in her first work are darker too, and contribute to making a truly unique work.»

«It is thanks to the “de luxe” edition style, popular for the time, that we can begin to appreciate the finesse of her line and the poetic harmony of her colors. She became, little by little, an outstanding artist of animal figures, as we see in her layer studies. A work document dating from 1948 illustrates how precise was the manner in which she worked. The work document, done a year earlier than her completion of the Alice illustrations, show a girl surrounded by forest animals, in an earlier from than the one we know of the little girl we see on page 21. This composition, to the little girl, is found later in The Book of Enchanted Beasts, in a new variation spanning two pages with the same theme.»

«In a file given only to us, an American publishing house announced around 1953 that the work Il etait une fois [The Fairy Tale Book] “is considered one of the most beautiful books for children published in France. It is interesting to note the number of copies anticipated for the first edition (20,000 for example) is more than three times higher than the average first edition of 5000 copies. This indicate the confident the editor had in the popularity of Adrienne Segur’s illustrations and the quality of her work.” The editor collaborated with the printer Hemmerle, Petit et Cie, which is a huge indication of the quality. However, it seesms that some of her colleagues may have regretted the chosen format. Thus, a press kit contained an unsigned article stated, “It is nevertheless regrettable that the large format prevents the spread of the books to an even larger number of readers.” Around the same time, Flammarion’s attention was perhaps more focused on the small formats of Pere Castor… Adrienne’s drawings were thus not the vanguard of “popular” editions.»

«The contract that bound Adrienne Segur to Flammarion, signed in 1956 for one volume to appear in 1957, has many clauses. Tasked in this document with illustrating different tales of Hans Christian Andersen in the usual format, the contract specified the number of images to be provided (16 or 8 inset in the text in black or 8 in colors) and the price that would be paid: 60,000 francs for the black and white boards, and 90,000 francs for the boards in color. Flammarion reserved the right of modification on these works, for which it had negotiated complete property rights with the artist (It was mentioned that she was not a member of the Syndicat of Artistic Propriety and so empowered to act as legal owner of the rights granted.) It was also stipulated that Adrienne Segur would see 50% of the income from the reproduction of her drawings in foreign countries. Eventually, her work would be translated and re-edited during the 1960s in English, German, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese and Swedish, sometimes markedly changing the exterior of the original French version: Buckram boards for the first flat laminating, pink-toned ornamentation for the English speakers,… The English version was translated by the poet Marie Ponsot.».

«Virtually unknown personally, Adrienne Segur’s illustrations of the best-known children’s stories were thus, thanks to her choice of editor, known worldwide. Popular fashion has changed considerably, and the style of books for children as well. It would require a daring spirit to publish a new version of the same Nutcracker or Alice of Adrienne Segur! And one would be crazy to dare to imagine, as Claude-Anne Parmegiani, a new edition of Enchanted Beasts in a small format. This last children’s book professional, commenorates Adrienne in Les Petits francais illustres in 1989, the following dedication: In her initial works, she adopted a childish graphic style, destined to overcome its own clumsiness. Thereafter, she would overcome this difficulty, falling into its opposite excess, but continually demonstrating her artistic skills. She then employs a style, which impacts the preciousness of the early style, in a more formal illustrations of coquettish girls! Success never belies her work as with the public acclaim of our day, as if a response to this strange caricature of an analsyis.»

«Thanks to funds miraculously provided by Christian Bookshop, a good many of her working documents and origial designs, the layers on which she worked, even the proofs she corrected finely in her own hand, it is possible to grasp the full extent of the work and the range of this artist. As gift-books for children, her albums were a landmark for a generations little girls, who dreamed of being like the small women-girls with the sad faces, of her princesses with the wavy hair, surrounded by jewels and benevolent animals, and that focus first and foremost on the value of feeling. One little girl loved the incredible skill in Adrienne Segur’s Nutcracker designs that were given as a reward, other little princesses protected by their enchanted beasts — for each a different Adrienne Segur and for all an illustrator who understood the fairy tales… to the point of becoming them.»

The website also provided a list of her works: we can see a Nutcracker in 1953, one Enfant et les Sortilèges from 1967 (a charming and visionary opera by Ravel), the famous Fairy-Tale Book from 1951 and, of course, Alice in Wonderland from 1949.

Lot of later illustrators, however, are highly influenced by Disney’s idea in the 1951 movie: a stone basement and an upper floor dramatically projecting. I thought you might be interested to know that this technique is called Jettying, probably from the Old French for projecting, and it’s a medieval trick to enlarge the upper floor without clogging the street. Specifically, the rabbit’s house in Disney’s idea uses solid stone for the first floor and the upper floor is half-timbered with white plastered infill.

As it will be obvious from the inside, the straw roof is supported by what we call a cruck, a frame in curved timber, to give it a chubby look and to prepare it for when Alice will grow to fill it and treat the roof as a wig she can scratch in puzzlement. Again, the strategy here is to make it more funny than claustrophobic, while in the book it’s one of the passages our little girl plainly fears she’ll die a horrible death.

Mary Blair’s concept art was even more trippy, with something like a pair of legs coming out of the chimney even before Alice goes in. You can see it here.

If you like this style, you might also enjoy the work by Moritz Kennel, if you remember him: his Alice is published by Phaidon in 1975 and is always rather trippy. There’s a squirrel on top of the house and he looks puzzled too. Probably by the fact that the sun is in front of the tree. Amazing.

Drifting away from Disney and looking for some unusual renditions is not easy, but if you keep digging you’ll find lots of interesting stuff.

Japanese illustrator Takako Hirai collected some Alice illustrations and you can find a nice review here. Among them, there’s a wonderful concept of a rabbit’s house that’s growing on a branch as a rosebud. The cottage is a lot more luxurious than the one depicted by Disney, still has parts in jettying and a filled timber-frame portion, but the basement is in wood (which is a lot more realistic than the stone first floor Disney went with in the final version).

Another historically-researched version is the one by Angel Dominguez (1996), although it would be more appropriate to show you this when (spoiler alert) the chimney sweeper comes into the picture: it’s a traditional cottage in bricks, as you would find thousands of them in the British countryside.

Among independent artists, one of my favourites has do be an Irish digital artist that goes by Nina Y. Her Alice is deeply influenced by Disney, but the idea of putting the house on top of a tree is charming enough, even without the nice creepy touch of the raven which seems to be almost waiting for Alice to grow a little more and crush herself to death. You can see the original artwork here.

“You wrecked my house, you bitch! I am never doing LSD with you again!”

2. I hope I shan’t Grow Anymore

Alice goes inside and we have very little description of the interior as well. What we know is that she finds gloves and a fan on a table, but she also finds something else and she’s well on her way to alcoholism by now.

[she] was just going to leave the room, when her eye fell upon a little bottle that stood near the looking-glass. There was no label this time with the words “DRINK ME,” but nevertheless she uncorked it and put it to her lips. “I know something interesting is sure to happen,” she said to herself, “whenever I eat or drink anything: so I’ll just see what this bottle does. I do hope it’ll make me grow large again, for really I’m quite tired of being such a tiny little thing!”

The absence of a label warning that the bottle is “not poison”, like the first time, is another way of telling us that she’s slipping more and more into the acceptance of that dangerous world of wanting to grow up, like a reverse Peter Pan. But the bottle has undesired effects.

It did so indeed, and much sooner than she had expected: before she had drunk half the bottle, she found her head pressing against the ceiling, and had to stoop to save her neck from being broken. She hastily put down the bottle, saying to herself “That’s quite enough—I hope I sha’n’t grow any more—As it is, I ca’n’t get out at the door—I do wish I hadn’t drunk quite so much!”

And who hasn’t uttered those words while bumping their head on the ceiling and being unable to reach the door?

This is of course one of the most illustrated scenes, starting from the original one – John Tenniel – who’s really bad at drawing Alice, as we have seen, and who this time gets away with an unnaturally twisted position that fits the narrative.

The scene is highly claustrophobic, and Tenniel succeeds in conveying that feeling. Other illustrators are more cheerful and, as it happens with Alice, coat everything with sugar. And, as you know, I’m not fond of that.

Alas! It was too late to wish that! She went on growing, and growing, and very soon had to kneel down on the floor: in another minute there was not even room for this, and she tried the effect of lying down with one elbow against the door, and the other arm curled round her head. Still she went on growing, and, as a last resource, she put one arm out of the window, and one foot up the chimney, and said to herself “Now I can do no more, whatever happens. What will become of me?”

As you can see, Alice doesn’t gracefully puts her arms out of windows and her legs out of floor-levelled doors: she’s twisted and uncomfortable, and I’m not saying that’s easy to illustrate. In this, some of the original sketches by David Hall, for Disney’s first attempt of putting Alice on the screen, seem to be wanting a far less quiet scene. You can see a lot of them here, but I particularly like this one, where the point of view is from outside and you can see all the rabbit’s things being displaced by Alice growing up.

Going back in time, we can also try and see how classical illustrators tried to manage with this difficult scene: Bessie Pease Guttman for instance decides to convey surprise and stops right before Alice grows enough to have to push pieces of herself out of the rabbit’s window and chimney.

The scene has different levels of drama. Charles Robinson for instance decides to show us an Alice that’s clearly chilling in the Rabbit’s house and doesn’t seem to be particularly worried of being crushed to death within its walls.

This graceful, unaffected position is similar, as you might expect, to the one chosen by Will Pogany for his “jazzy Alice”. She doesn’t have a care in the world and she’s posing for the shot.

Margaret Tarrant focuses on her bumping her head, and stops right there. It fits her style but we’ll see that she’s also able to illustrate strong emotions, particularly when Alice grows up too much again and gets attacked by a rather cranky pigeon.

More recent illustrators are sometimes more perceptive towards the troubling subtext of the scene. It’s the case of Rosemary Honeybourne, whom we have already seen for Alice eating the cake, for her Canadian edition, and who was published in 1969 by McClelland and Stewart.

A different approach is chosen by Peter Weevers (Hutchinson, 1989): his Alice looks more miserable than scared or worried, but it works too and she’s bound to come out of it with quite a crick in the neck.

Among contemporary artists, a nice one is the illustration by François Amoretti for this edition. She doesn’t grow into the house: she breaks out of it, and is far less passive and mild than the usual depictions. That’s something I’m bound to like.

Another one who we have already seen, and who succeeds in drawing the twisted, uncomfortable position Alice finds herself in, is Eric Kincaid in a German edition published by Basserman in Munich. It’s richly illustrated and you can see a lot more pictures here.

And this is where we leave her, hoping to be able to get her out of there next Sunday.