Qualche giorno fa, ho scritto un paio di considerazioni sulla parte 1 del Integrating HBIM Framework Report, un documento britannico sull’implementazione del BIM per la conservazione e l’intervento sul patrimonio storico, sviluppato nel 2016 dal Council on Training in Architectural Conservation (COTAC). La seconda parte però – Conservation Influences – è quella che personalmente considero più interessante.

Conservation Influences

It is generally recognised that the built heritage is under threat from a variety of influences – including a lack of knowledge by the professions, and from a lack of understanding by the ‘main-stream’ construction industry. But what is ‘main-steam’ when the entire sector virtually operates in two equal halves?

Il punto di partenza del testo è che le professioni nel settore delle costruzioni si suddividono ormai in due categorie: la categoria di coloro che creano sub-prodotti specialistici e coloro che invece scelgono, assemblano e compongono quello che chiamiamo progetto. Una visione già molto distante dal progettista come plasmatore di spazi, come tagliatore di diamanti, che invece adottiamo in Italia.

‘Today, most architecture is subject to the design of components by others …… The trusses, cladding systems, windows and doors and the kitchens, wardrobes and bathroom elements all the way down to the door handles have already been “pre-designed”, so what is it that the architect does? As Farrell Review Expert Panel member Sunand Prasad has said, the role of the architect today is increasingly about selecting, synthesising and integrating, and they are well placed to do this.’

Farrell Review, Aprile 2014

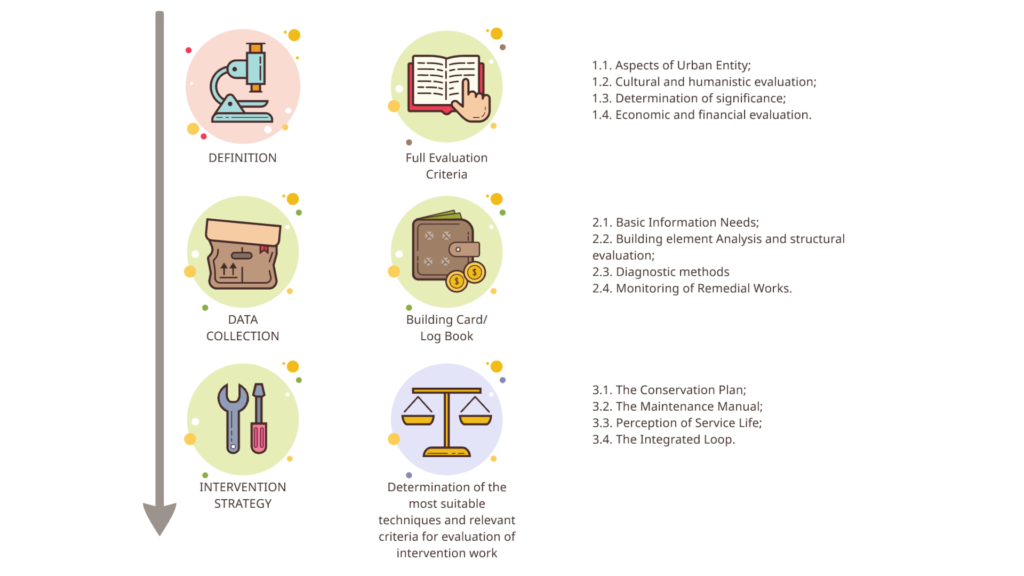

I criteri del documento (HBIM Framework Evaluation Criteria, o FEC) sono organizzati in tre fasi:

- Definizione;

- Raccolta di dati;

- Strategia di intervento.

Mi concentrerò principalmente sulla fase di Definizione, forse lo spunto più interessante del framework perché preliminare anche al rilievo, ma vi riporto schemi e citazioni anche dalle altre fasi.

1. Definizione

La fase comprende a sua volta 4 step:

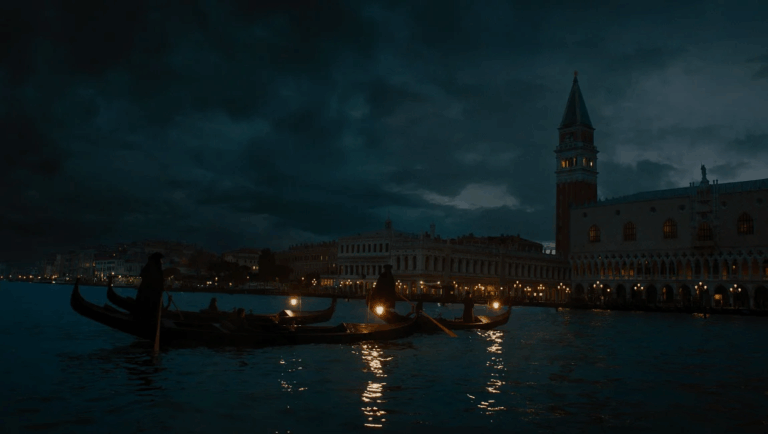

Step 1.1: Aspects of Urban Entity, ovvero l’impatto fisico ed emotivo dell’edificio nel tessuto urbano.

Step 1.2: Cultural and Humanistic Evaluation, ovvero il valore artistico, architettonico, archeologico e scientifico del bene, unito all’impatto che il bene può vantare su sfere come quella emotiva, sociale e simbolica.

Step 1.3: Determination of Significance, ovvero la valutazione sull’importanza del bene.

Step 1.4: Economic and Financial Evaluation, ovvero la valutazione economica e finanziaria del bene e del relativo intervento.

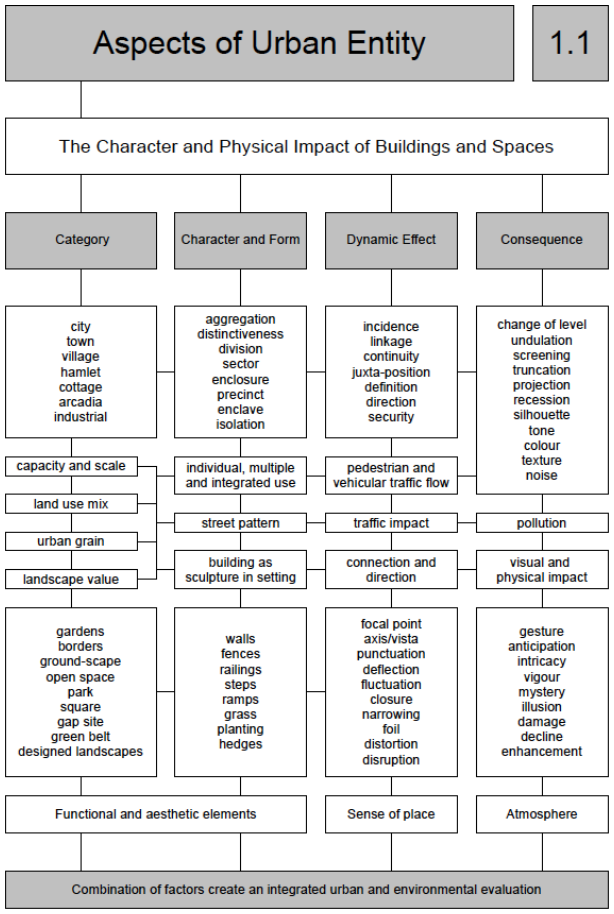

Step 1.1: Aspects of Urban Entity

Il collocamento fisico degli edifici in un contesto urbano e il rapporto dell’edificio con i suoi spazi circostanti hanno un profondo impatto sulle esperienze degli individui. La dimensione, la scala e il valore del patrimonio storico, l’interazione delle parti che lo costituiscono e delle sue forme con il contesto, l’impatto visivo ad esso associato e le sue conseguenze, giocano un ruolo fondamentale nell’accettazione di ciò che deve essere considerato per conservare, riutilizzare e restaurare in modo sensibile ciò che consideriamo patrimonio storico. Questa la premessa da cui parte questo step, che si occupa di analizzare ogni aspetto del bene dal punto di vista urbano.

Elementi funzionali ed estetici si individuano nelle categorie che costituiscono l’ambiente costruito (città, villaggio, caseggiato, complesso industriale, quelli che la ISO 12006 chiamerebbe complessi ed entità) e nelle categorie che costituiscono il bene in sé, quelle che nel nostro modello sarebbero le categorie o le classi, ma in questa fase l’edificio viene considerato un scultura nel suo contesto.

L’intorno viene analizzato in termini di rete stradale, connessioni con altri punti focali del contesto,

Step 1.2: Cultural and Humanistic Evaluation

Il passo incorpora anche un ragionamento riguardo alla rarità/unicità del bene, oltre al suo inserimento non solo nel contesto storico ma anche ambientale e naturalistico: potrebbe infatti non avere altro valore se non quello di ospitare fauna protetta, ma questo non lo renderebbe meno importante di un bene sotto vincolo per il suo valore storico.

Il complesso nell’insieme viene valutato nel suo contesto, nel suo grado di integrazione e dal punto di vista legislativo.

La valutazione sulla rarità richiede invece parametri tipologici (un bene unico nel suo genere) o relativi alle personalità coinvolte nella sua creazione, ma considera anche se il bene è intatto o meno, la sua importanza in relazione al contesto, la sua datazione e le tradizioni che lo coinvolgono.

Dal punto di vista culturale, si opera su due fronti: quello funzionale e quello artistico, mentre il punto di vista umanistico valuta l’impatto del bene dal punto di vista emotivo, il suo ruolo nella memoria collettiva e nel corpus storico/folkloristico, come il suo eventuale significato simbolico.

Step 1.3: Determination of Significance

La rilevanza del bene può essere a diverse scale, da quella locale e regionale a quella nazionale e il suo grado di vincolo potrebbe essere imposto da una normativa nazionale tanto quanto da organi sovranazionali e internazionali come l’UNESCO.

L’importanza, il significato del bene viene quindi valutato su 4 fronti:

- il suo status a livello internazionale;

- la valutazione sull’importanza del bene effettuata dagli organi legislativi nazionali;

- la rilevanza del bene nel suo contesto, con l’identificazione di dati sulla qualità architettonica, sulla sua forma e funzione, il suo ruolo nel contesto urbano e il suo livello di integrazione nel tessuto circostante;

- l’importanza del bene dal punto di vista umano e sociale.

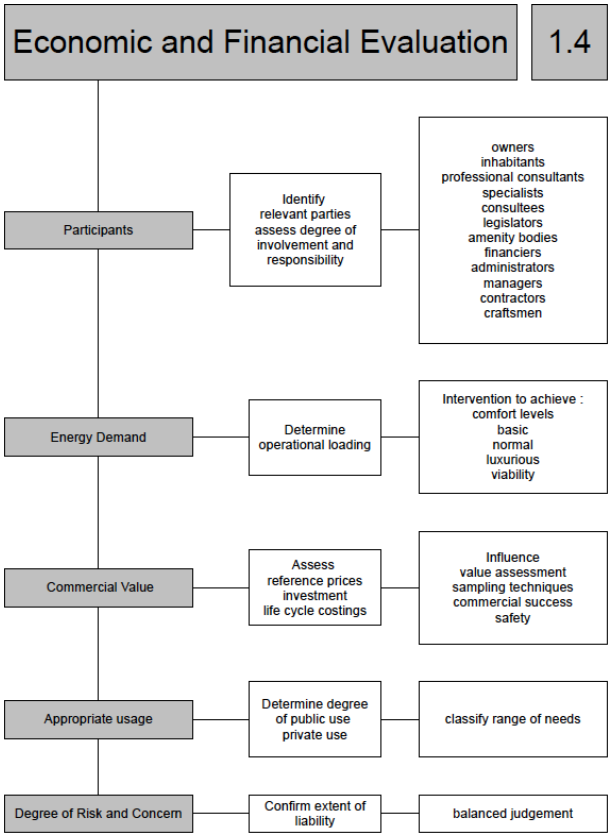

Step 1.4: Economic and Financial Evaluation

In ultimo, la valutazione economica comprende i bisogni finanziari per il restauro o la conservazione del bene, con prezzi di riferimento specifici per gli intervento specialistici, ma tiene in considerazione una valutazione sul livello di intervento per raggiungere confort e sicurezza, include la valutazione del rischio e pone particolare attenzione agli aspetti energetici.

2. Raccolta di dati

La fase di rilievo vera e propria avviene solo dopo l’assessment preliminare, perché – esattamente come in un modello informativo – vi è necessità di fornire obiettivi specifici e specifici ambiti di indagine.

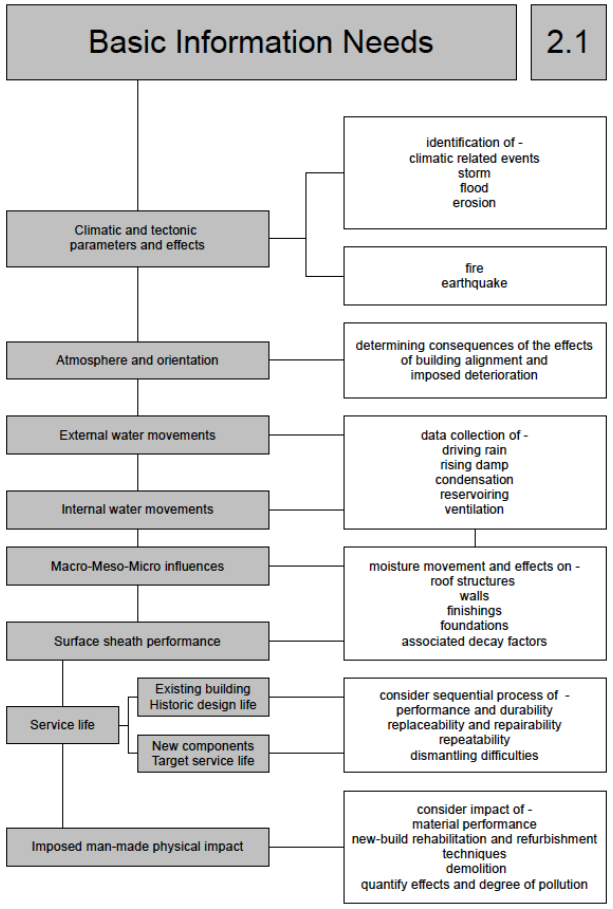

Step 2.1: Basic Information Needs. La raccolta delle informazioni di base sul contesto del bene (geologiche, ambientali, climatiche e in generale dipendenti dalla sua posizione);

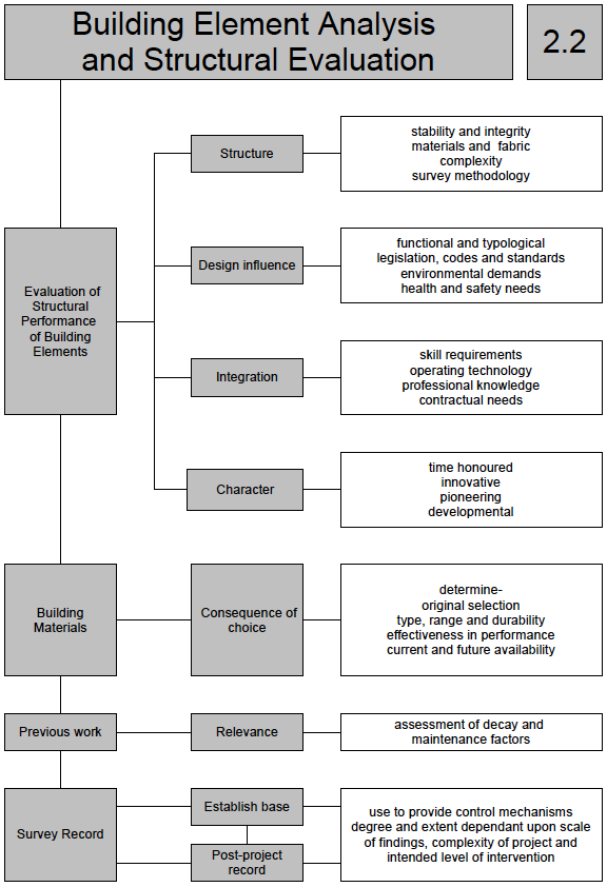

Step 2.2: Building Element Analysis and Structural Evaluation. Analisi puntuale sugli elementi dell’edificio e in particolare sulla sua integrità strutturale, dal punto di vista formale e quantitativo, funzionale, materico e temporale.

Step 2.3: Diagnostic Methods.

Step 2.4: Monitoring of Remedial Works. Una pianificazione sulla frequenza di ispezione e monitoraggio, che ci porterebbe sull’accidentato terreno del digital twin.

Identifying and understanding the full range of Geological, Environmental, Locational and Climatic Parameters and their Effect on the materials used in the original construction have a profound impact on how emerging problems are assessed and resolved. Here, factors such as material mineralogy, porosity, function, water run-off performance, detail, form and volume could all be considered relevant.

– COTAC BIM4C Integrating Report Part 2: Ingval Maxwell: February 2016

In the process, a key aspect will be the level and extent of survey that is undertaken in support of the project. This will inevitably be exercised in different degrees, commensurate with needs and intentions. It will range in technique from the relatively superficial to the detailed archaeological. It can be used to plan for and monitor progress of intended levels of intervention and, in its own right, will emerge as a valuable document with numerous future uses.

– COTAC BIM4C Integrating Report Part 2: Ingval Maxwell: February 2016

In broad terms, the processes under consideration are liable to range from simple to sophisticated, appropriate to inappropriate, economic to expensive, and non-destructive to destructive in their use.

– COTAC BIM4C Integrating Report Part 2: Ingval Maxwell: February 2016

As set out in Step 2.4, by taking an elemental approach to assessing features (roof, walls, floors and foundations) the identification, quantification and determination of the effectiveness of relevant remedial works should emerge. This can then be followed with a detailed investigation into the associated importance of each, its finish; what energy demand is anticipated and achieved; how previous repair work has performed; and how the degree of associated risk and concern might be measured.

– COTAC BIM4C Integrating Report Part 2: Ingval Maxwell: February 2016

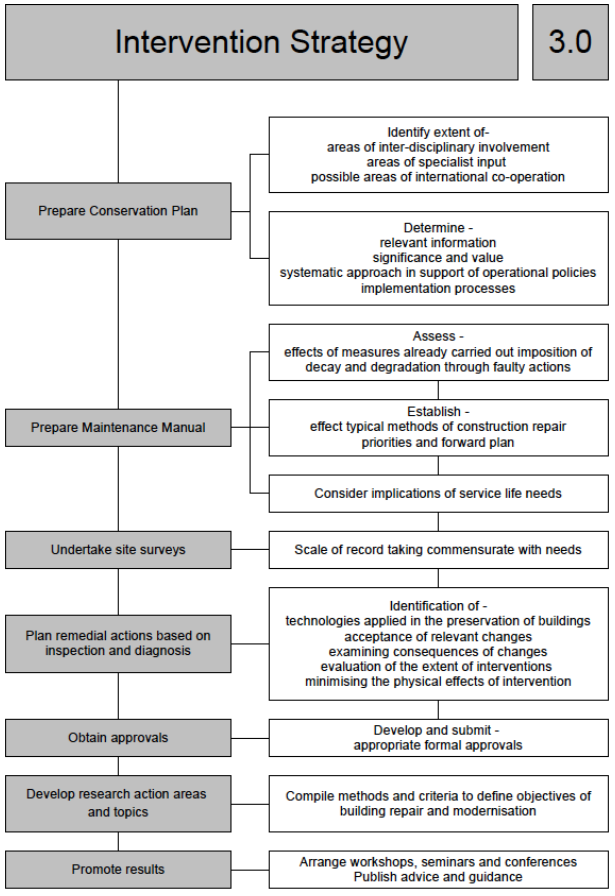

3. Strategia di intervento

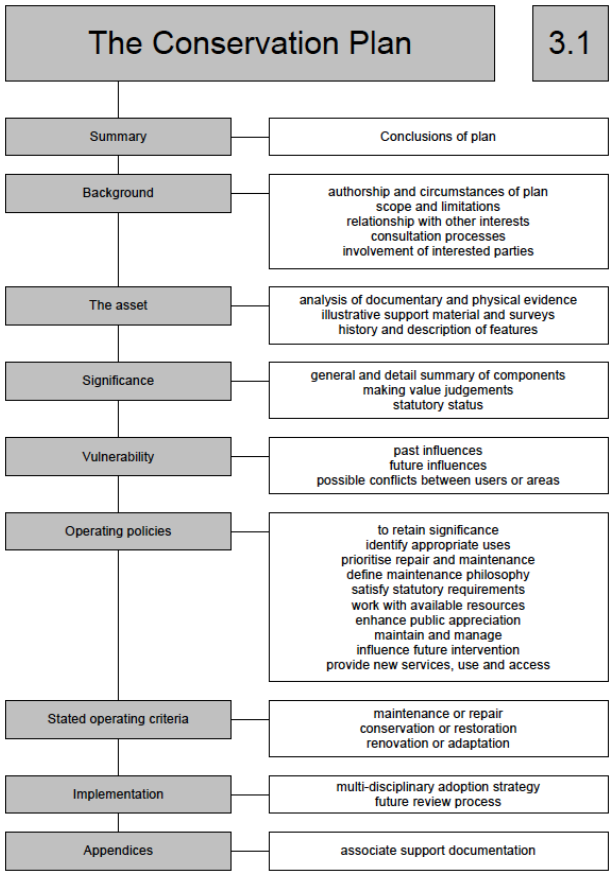

Step 3.1: Conservation Plan.

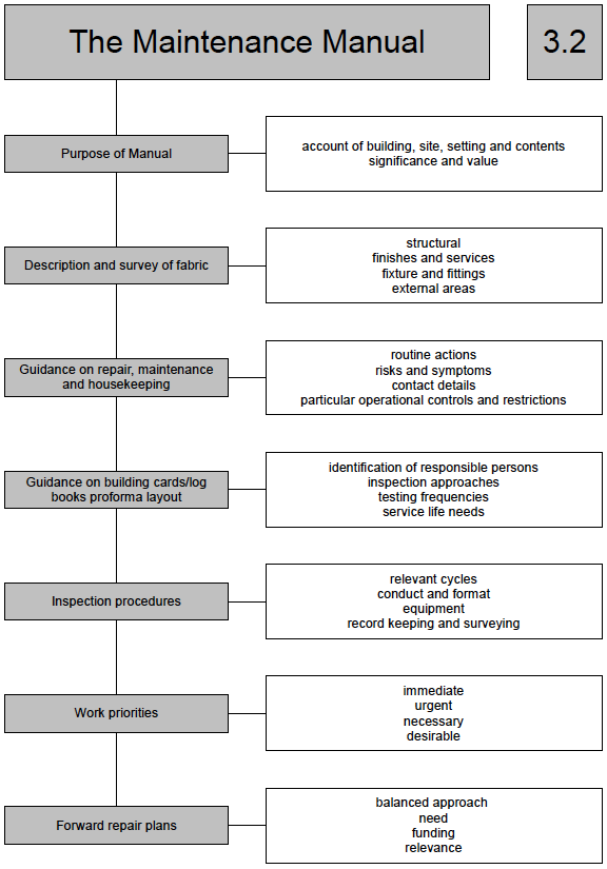

Step 3.2: Maintenance Manual.

Step 3.3: Perception of Service Life.

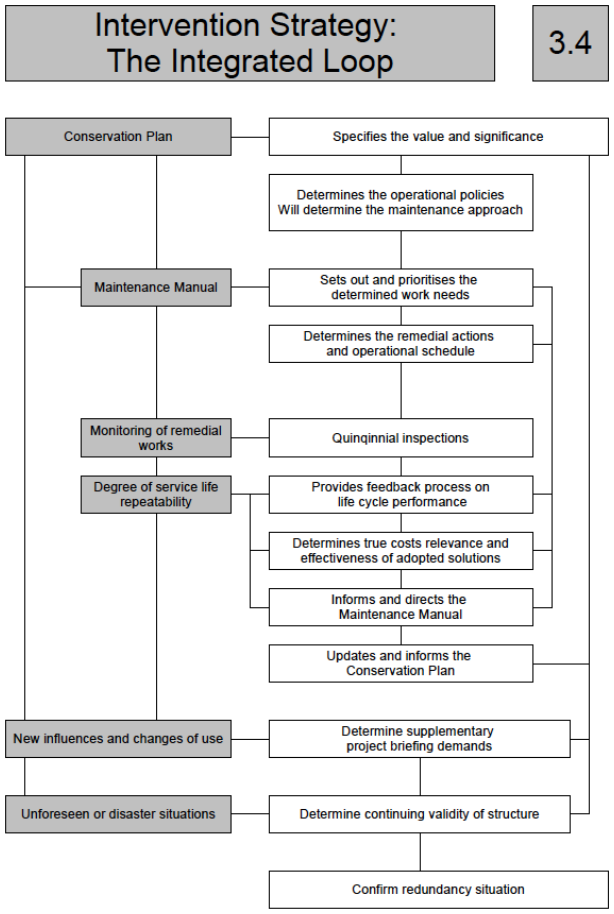

Step 3.4: Intervention Strategy: The Integrated Loop.

As the various HBIM steps are worked through in detail, an increasing level of pertinent information should flow, and come together. This should include assessed details of the –

– COTAC BIM4C Integrating Report Part 2: Ingval Maxwell: February 2016

• Physical and environmental conditions

• Legislative and associated constraints

• Buildings physical condition

• Identified analytical processes

Step 3.1: Conservation Plan

Within a structure outlined in Step 3.1, topics relevant to the plan might include detail on-

– COTAC BIM4C Integrating Report Part 2: Ingval Maxwell: February 2016

• Defining the parameters of urban spaces

• Policy making requirements in social, cultural and architectural terms

• Assessing the effects of tourism, linked analysis and relevant economic issues

• Translating conservation needs into renewal project planning processes

• Effecting appropriate surveying techniques

• Defining the relevant level of repair work

• Undertaking effective building maintenance

Step 3.2: Maintenance Manual

This document should be prepared in the form of a prescribed template, so that its relevance can be upheld, irrespective of the subject under consideration. Advice on how to undertake necessary housekeeping, repair work and maintenance should be offered, and guidance given on relevant tests, trials and monitoring needs. It should also help define alternatives to established problems so that the most relevant approach can be considered and prioritised for future adoption.

– COTAC BIM4C Integrating Report Part 2: Ingval Maxwell: February 2016

Step 3.3: Perception of Service Life

A significant factor in the effective maintenance of the built heritage is the need to accommodate repeated actions of repair and replacement.

– COTAC BIM4C Integrating Report Part 2: Ingval Maxwell: February 2016

Step 3.4: Intervention Strategy: The Integrated Loop

The underlying need in an era of sustainability thinking is to recognise the true value of what has been previously built and determine ways of ensuring its continuing validity. Inevitably, there will be occasions where a redundancy situation will arise but with a greater acceptance of the energy embodiment case, a more reasoned argument to ensure survival should emerge through core HBIM considerations.

– COTAC BIM4C Integrating Report Part 2: Ingval Maxwell: February 2016

No Comments