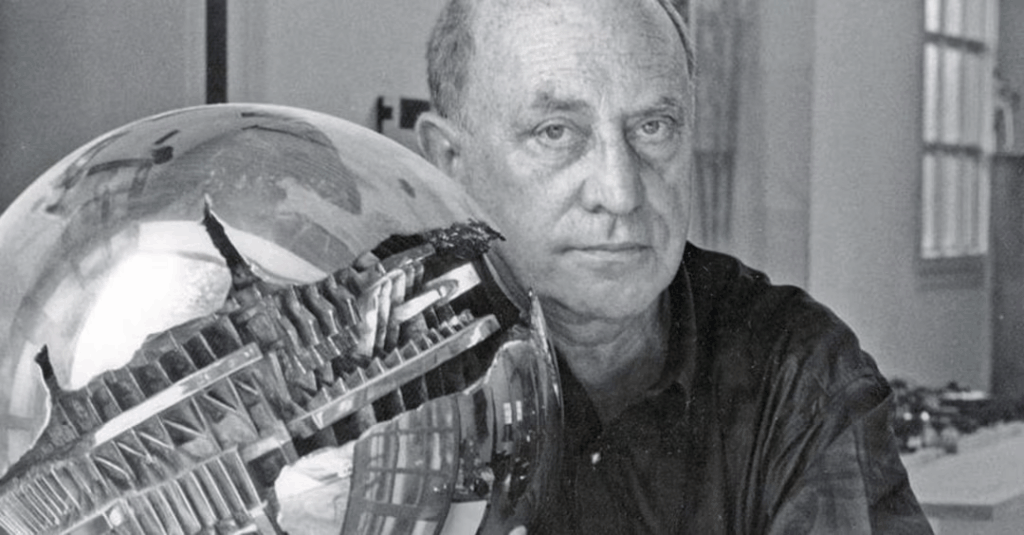

Yesterday, on the eve of his 99th birthday, Arnaldo Pomodoro passed away in Milan, the city he elected as his own to live and work in. I decided to honour his memory and his legacy with one of my urban itineraries.

A Life Dedicated to Sculpture

Born in Morciano di Romagna, Arnaldo Pomodoro was one of the most emblematic sculptors of the Italian 20th and early 21st centuries. Trained as a surveyor, his path into the arts was anything but linear, yet utterly transformative: he belonged to a generation of artists who emerged from the ruins of post-war Italy with a drive to reformulate the very language of sculpture, stripping away academic conventions in favor of material experimentation, symbolic abstraction, and conceptual depth.

His practice was rooted in a singular obsession: to “violate the perfection of the geometric form” and reveal its inner structure, what he described as “the complexity of the contemporary human condition.” His signature works — bronze spheres cracked open to reveal intricate inner mechanisms, spires, columns, and discs — are aesthetic and philosophical meditations. For over seven decades, Pomodoro’s career intersected with the worlds of architecture, theatre, literature, and politics. He collaborated with architects like Renzo Piano, staged theatrical sets for Beckett and Aeschylus, and engaged deeply with questions of time, memory, and collective identity.

Milan Is the Symbolic City of His Work

Though Pomodoro’s works are scattered across the globe — from the Vatican to Los Angeles, from Tehran to Brisbane — Milan is where his identity as an artist fully matured and where his legacy is most deeply rooted. It was in Milan that he settled in the 1950s and joined the cultural ferment that included Lucio Fontana, Piero Manzoni, and Bruno Munari. It was here that he held his first major exhibitions, developed his atelier and laboratory spaces, and founded the Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro in 1995, a cultural institution that continues to host exhibitions, preserve his archives, and promote critical engagement with contemporary sculpture.

Milan embraced Pomodoro as one of its own. The city’s streets, piazzas, and institutions bear the imprint of his vision: the “Disco Solare” in Piazza Meda, the “Sfera con Sfera” at La Triennale, the “Colonna del Viaggiatore” beside the Teatro Manzoni, and many others. These works exist in the daily rhythm of urban life, provoking reflection amid the noise of traffic and the anonymity of modernity.

A Memorial Itinerary

The death of Pomodoro marks the closing of a chapter in Italian art history, but not its end, as his works remain vital, present, and provocatively open to interpretation. A memorial itinerary through Milan is more than a homage; it is a gesture of collective reawakening.

By retracing his sculptures through the city, we engage not only with the material traces of his hands but with his vision of art as dialogue between form and void, surface and core, past and future. This itinerary invites us to see Milan through Pomodoro’s eyes: a city as sculpture, a body in transformation, a space layered with memory and potential. It offers a chance to slow down and observe what Pomodoro always made visible: the fractures, tensions, and beauty beneath the polished surface of things. In walking his Milan, we walk with him.

1. The Man and the Artist

1.1. From the Marche Region to Milan

Arnaldo Pomodoro was born in 1926 in Morciano di Romagna, a small town nestled between the rolling hills of the Marche and Romagna regions. His formative years were marked by the turbulence of Fascism and the Second World War, experiences that deeply shaped his sensibility toward history, rupture, and resistance. Initially trained in technical disciplines — he earned a diploma as a surveyor and studied stage design — his path to sculpture emerged gradually, through a synthesis of craft, curiosity, and intuition.

When Pomodoro moved to Milan, in the early 1950s, the city was in the midst of cultural and economic rebirth. It was here that he found fertile ground for experimentation and dialogue, frequenting circles that included artists, poets, designers, and philosophers. The city’s industrial character, dynamic architecture, and intellectual networks all played a formative role in his evolution. His early works combined metal, relief, and texture in ways that evoked both ancient inscriptions and futuristic landscapes, foreshadowing the symbolic vocabulary he would later fully develop.

Pomodoro’s breakthrough came in the 1960s, with his iconic Sfera con Sfera and Disco series. These works launched his international recognition, with commissions from the Vatican, the United Nations, and major institutions worldwide. Yet throughout his career, Milan remained his point of return: his studio, his archive, and his foundation were all rooted there, making the city both stage and sanctuary for his enduring creative inquiry.

1.2. The Poetics of Matter and Time

Pomodoro’s artistic language is grounded in paradox. He takes the perfection of geometric forms — spheres, columns, pyramids — and deliberately fractures them. What emerges is a sculptural tension between surface and interior, order and entropy, monumentality and fragility. His bronzes, deeply etched and incised, reveal inner worlds that seem ancient and mechanical, archaeological and alien, resonant with signs that escape precise decoding.

Time, in Pomodoro’s work, is not linear. His forms seem to hold time still while simultaneously revealing its erosion. They are fossilised yet futuristic, invoking ancient relics and space-age machines in the same gesture. His sculptures are often described as “ruins of the future” or “machines for memory”, phrases that reflect how he imbues matter with layered temporality. Bronze, his favoured medium, is both durable and malleable: a material of legacy and transformation.

Crucially, Pomodoro never saw sculpture as static. For him, it was a “process of thought,” a continuous unmaking and remaking of space. His hands bore not just form, but rhythm, excavation, and breath.

1.3. Connections with Architecture, Theatre, and the City

Pomodoro’s interdisciplinary sensibility sets him apart from many of his contemporaries. He never confined sculpture to pedestals or galleries; instead, he consistently sought to insert art into the fabric of life. Nowhere is this more evident than in his relationships with architecture and theatre.

In architecture, Pomodoro collaborated with leading figures of modern and contemporary design, including Renzo Piano and Vittorio Gregotti. His sculptures often inhabit architectural spaces not as decoration, but as spatial and conceptual counterpoints: the Labirinto installed in via Solari, for instance, is not merely a work to view but one to enter and experience, a sculptural space that echoes the structure of ancient temples and contemporary data networks.

In the theatre, Pomodoro designed sets for plays by Beckett, Pirandello, and Aeschylus, merging spatial abstraction with dramatic tension. His scenographies were immersive landscapes of steel and shadow, evoking emotional atmospheres more than literal backdrops. For him, the stage was another kind of sculpture: ephemeral, expressive, collaborative.

Above all, however, Pomodoro saw the city itself as a living theatre, and sculpture as a script carved into its architecture. In Milan, his works are embedded in the pedestrian flow, in institutional thresholds, and in unexpected corners.

2. The Urban Itinerary

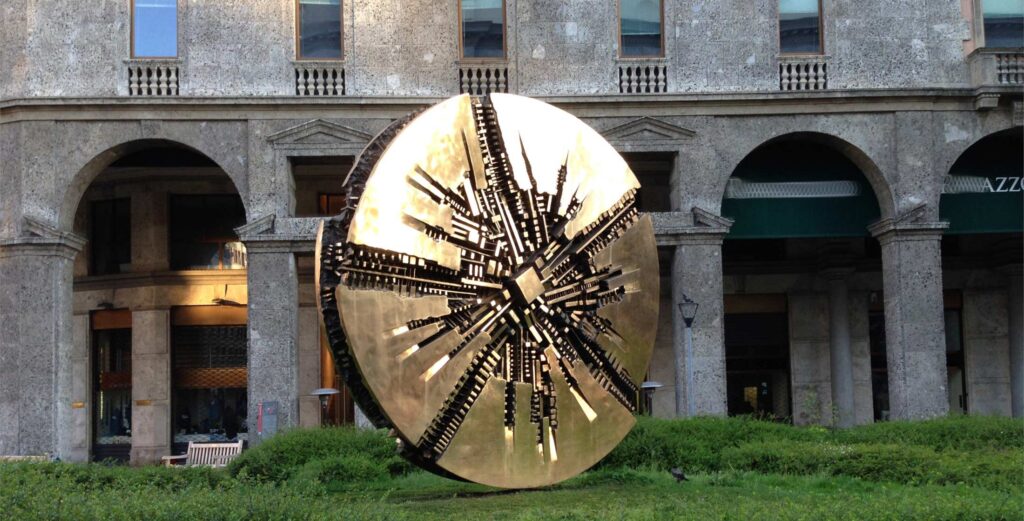

2.1. “Great Disc” – Piazza Meda

The Work

Located in the heart of Milan’s financial district, Arnaldo Pomodoro’s Grande Disco rises from the centre of Piazza Meda like an ancient celestial machine embedded in the city’s surface. Created in 1980, this monumental bronze sculpture — over 3 meters in diameter — stands on a reflective base, emphasizing its circular symmetry and internal complexity. At first glance, the work resembles a massive coin or gear, but upon closer inspection, its perfect surface is interrupted, opened, almost wounded, revealing a dense interior of sharp-edged geometric fragments, mechanical interlocks, and stratified volumes.

Unlike static monuments, the Grande Disco seems to rotate conceptually on its axis. The play between light and bronze gives it a shifting presence throughout the day — golden at sunrise, ominous at dusk —echoing its title and reinforcing the metaphor of the sun as a timeless, generative force. The sculpture evokes both the cosmic and the mechanical, inviting interpretations that range from metaphysical meditations on time and entropy to reflections on the technological unconscious of modern life.

The Context

Piazza Meda itself is a striking example of 20th-century urban planning: geometrically organised, framed by banks and commercial buildings, yet largely anonymous in character. Pomodoro’s intervention disrupts that anonymity. Rather than embellishing the space, the disc redefines it and offers a counter-monumental presence: abstract, introspective, and tactile.

The work’s scale is imposing but not overpowering, in the large context of the square; its presence transforms the pedestrian experience, introducing an unexpected pause in a zone otherwise dominated by business and traffic. For Pomodoro, the city is not merely a backdrop but a co-author: the disc’s polished and fractured bronze reflects the sky and surrounding facades, creating a constantly shifting dialogue between matter, light, and architecture.

But the disc hasn’t always been here. On 12 October 1976, the Great Disc was installed in Vigevano, in Piazza Ducale, but various controversies arose around this work, due to the stark contrast between ancient and modern, so much so that in 1979 the sculpture was moved permanently to Milan. During the construction of the Piazza Meda car park, which lasted about four years (until mid-2010), the sculpture was placed in Lanza, in front of the Piccolo Teatro di Brera.

Tips for the visit

- Location: Piazza Meda, easily reachable by Metro M3 (Montenapoleone or Duomo);

- Best time to visit: early morning or late afternoon, when the sunlight emphasises the sculpture’s depth.

2.2. Disc in the form of a desert rose – Gallerie d’Italia, Piazza della Scala

The work

Among Arnaldo Pomodoro’s most poetic and enigmatic creations, Disco in forma di rosa del deserto is a monumental bronze sculpture created between 1993 and 1995. Installed in the garden courtyard of the Gallerie d’Italia on Piazza della Scala, the work draws its title from the natural formation known as a “desert rose”, a mineral cluster shaped by wind and sand, delicate in form yet forged through violent erosion.

Pomodoro’s interpretation reimagines this crystalline phenomenon on an architectural scale: a bronze disc fractured and folded into radial, sharp-edged layers, its structure alternately imploding and expanding. Unlike the more contained geometries of his Sfera or Disco series, this work suggests an explosive, centrifugal force, an act of geological becoming rather than mechanical dissection. Its surface, complex and jagged, captures the paradox at the heart of Pomodoro’s poetics: solidity that feels fluid, abstraction that remains tactile, and destruction as a form of creation.

The context

The setting of the Disco in forma di rosa del deserto is significant: it resides in the internal courtyard of the Gallerie d’Italia, a museum housed in the former headquarters of Banca Commerciale Italiana, in one of Milan’s most institutional and historic zones. This space — a cloister-like garden framed by neoclassical facades — is a place of silence and order. Pomodoro’s intervention subverts that order without negating it: his sculpture sits like a geologic intrusion in a financial temple, a reminder of natural, uncontrollable time against the measured time of capital and commerce.

The piece was acquired by Intesa Sanpaolo as part of its growing engagement with contemporary Italian art. It not only anchors the museum’s sculpture collection but also offers a critical bridge between classical architectural heritage and the radical abstraction of the 20th century.

Tips for the Visit

- Location: Gallerie d’Italia, Piazza della Scala (entrance from Via Manzoni or Piazza della Scala);

- Museum access: entry to the courtyard is usually included in general admission; some exhibitions allow access to the courtyard freely;

- Best time to visit: midday, when the natural light filters through the courtyard and emphasises the sculpture’s layers and textures.

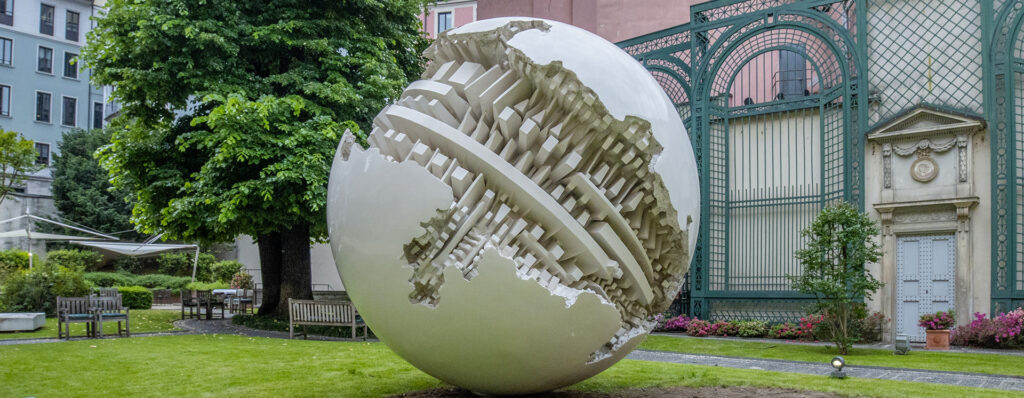

2.3. Sfera Grande – Gallerie d’Italia, Piazza Scala (Garden Courtyard)

The work

Installed in the Giardino di Alessandro, a secluded courtyard within the Gallerie d’Italia complex in Milan, Sfera Grande by Arnaldo Pomodoro is a striking example of the artist’s early experimentation with material, scale and form. Realised in 1966 and measuring an imposing 350 cm in diameter, this version of the iconic sphere is made not of bronze—as many others in Pomodoro’s global series are—but of fibreglass, a choice that emphasises its smoothness, lightness, and inner luminosity.

Unlike other works in the Sfera con Sfera series, which dramatize mechanical interiors rupturing through geometric containment, this Sfera Grande offers a more unified surface, yet still fractured, incised, and symbolically exposed. Its gleaming shell captures and distorts the surrounding architecture and landscape, drawing the viewer into an unstable, shifting perception of space.

“The sphere is a magical form. Its polished surface reflects what surrounds it, returning a perception of space different from the real one, and it creates mystery.”

This perception-altering quality is at the heart of Pomodoro’s sculptural philosophy: to intervene not by explaining, but by disorienting, reframing our experience of space, matter, and memory.

The context

La Sfera Grande was installed in the Giardino di Alessandro as part of the broader project to enhance and recontextualise Milan’s modern and contemporary collections within the Gallerie d’Italia. This discreet, elegant courtyard — bordered by classical architecture and shaded by plant life — becomes a meditative setting for the sphere’s reflective and symbolic presence. Here, the artwork establishes a powerful visual and spatial dialogue with both history and modernity: the garden becomes not just a backdrop but a theatrical chamber. Its fibreglass construction, unusual in Pomodoro’s large-format sculptures, contributes to a sensation of weightlessness, almost astral detachment. And yet, it is firmly anchored in the cultural memory of the city, a visual and tactile punctuation of Milan’s sculptural landscape.

2.4. Colonna del Viaggiatore – Museo del Novecento

The work

Created in 1959, Colonna del Viaggiatore is one of Arnaldo Pomodoro’s earliest and most evocative works. Housed in the Museo del Novecento, Milan’s premier institution for 20th-century Italian art, this bronze column stands at a pivotal moment in Pomodoro’s artistic evolution, before the geometric perfection of the Sfera and Disco series, yet already revealing his fascination with layered time, encoded surfaces, and sculptural memory.

The column appears like an ancient stele, a totem etched with mysterious signs, as though inscribed in a language no longer spoken but still felt. Its verticality evokes both stability and passage, standing like a relic retrieved from the future or an artefact displaced from antiquity. The surface is densely worked: fractured, scratched, incised with delicate marks that resemble writing, cartography, or circuitry. This texture is not ornamental but essential, and it’s Pomodoro’s early exploration of surface as semantic space. Unlike later works that openly expose mechanical interiors, the Colonna remains closed, its mystery sealed, its message buried in metal. Yet this restraint amplifies its poetic power.

The context

The sculpture is part of the permanent collection of the Museo del Novecento, located in the Palazzo dell’Arengario on Piazza del Duomo. The museum traces the development of Italian art from the early avant-gardes through Arte Povera and Conceptualism, and Colonna del Viaggiatore holds a unique position within that arc: it bridges modernist abstraction with a personal mythology rooted in memory, archaeology, and symbolic language.

Placed among works by Fontana, Melotti, and Manzoni, Pomodoro’s column forms part of the dialogue that defined Milan’s post-war art scene. It reveals how, even in his early years, he was already carving a distinct path—one that merged sculptural form with the metaphysical ambitions of poetry and philosophy.

The museum also hosts Sfera n.5 from 1965.

Tips for the Visit

- Location: Museo del Novecento, Piazza del Duomo, 8 (entrance via Arengario);

- Access: included in the general museum ticket; accessible year-round;

- Best time to visit: weekdays, mid-morning, when the museum is quieter.

2.6. Sala delle Armi – Casa Museo Poldi Pezzoli

The work

In 2000, Arnaldo Pomodoro was invited to reimagine the Sala delle Armi (the Armory Room) in the historic Casa Museo Poldi Pezzoli. Unlike his public monuments or freestanding bronzes, this intervention belongs to a rarer dimension of his oeuvre: site-specific scenography within historical architecture.

The commission did not involve creating a new sculpture in the traditional sense. Instead, Pomodoro was asked to design the setting for a collection of Renaissance and Baroque arms and armour, housed in one of Milan’s most refined private museums. The result is not a display case, but a sculptural environment where contemporary abstraction and historical craftsmanship are brought into radical conversation. Pomodoro conceived the room as a theatrical proscenium, using burnished bronze panels, oxidised steel, and a subtly controlled lighting scheme. His intervention envelops the collection with dark, incised surfaces that echo his signature language of fractured geometries and mysterious signs. The walls and ceiling — structured in panels of his signature engraved metal — become an immersive text, surrounding the historical artefacts with symbolic resonance rather than literal explanation.

The context

Casa Museo Poldi Pezzoli is one of Milan’s most treasured cultural sites: once the private home of Gian Giacomo Poldi Pezzoli, it was transformed into a museum in the late 19th century. Known for its intimate atmosphere and extraordinary collections — from Botticelli to medieval tapestries — the museum invites a slow, almost domestic encounter with art. It also houses of temporary exhibitions that are always excellent, such as Andrea Solario‘s this season, Piero della Francesca‘s last season, and Richard Ginori‘s.

Pomodoro’s intervention in the Armoury Room represents a deliberate tension. His language is resolutely modern, even futuristic, while the arms on display evoke a chivalric and militarised past, yet it is precisely this temporal dissonance that produces meaning. The juxtaposition invites questions: What are these objects of war doing in a shrine-like chamber designed by a pacifist sculptor? What happens when form overtakes function, and armour becomes an aesthetic relic? In this way, the Sala delle Armi becomes a conceptual installation: Pomodoro envelops, ritualises and disrupts history.

Tips for the Visit

- Location: Casa Museo Poldi Pezzoli, Via Alessandro Manzoni, 12

- Access: included in general museum admission; photography may be limited

- Best time to visit: late afternoon, when natural and artificial light create a layered chiaroscuro in the room.

2.7. The History of Copper – Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia

The work

While most of Arnaldo Pomodoro’s sculptures are known for their monumental forms and metaphysical implications, his contribution to the Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci underscores another facet of his artistic identity: a profound and enduring relationship with material, particularly metal. In the permanent exhibition “History of Copper”, Pomodoro’s work is presented alongside tools, artefacts, and technological innovations that trace humanity’s evolving interaction with this foundational element. Copper — malleable, conductive, and among the first metals manipulated by humans — is more than a raw material for Pomodoro: it is an ancestral memory, a substance charged with historical, symbolic, and tactile meaning.

The context

The museum is one of the most significant institutions of its kind in Europe. Housed in a former 16th-century monastery, the museum juxtaposes classical architecture with interactive, multidisciplinary exhibits focused on physics, engineering, transportation, and materials science.

The History of Copper exhibit is designed to explore copper’s long history — from prehistoric tools and Roman metallurgy to modern applications in electronics and architecture. Pomodoro’s contribution is located at the intersection of material history and artistic language, offering a rare opportunity to see how an artist’s formal vocabulary evolves from deep material knowledge. By featuring Pomodoro in this context, the museum affirms his intellectual kinship with inventors, metallurgists, and engineers, all of whom, like sculptors, give form to resistance, pressure, and transformation.

Tips for the Visit

- Location: Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci, Via San Vittore 21;

- Access: included in general museum admission; “History of Copper” is part of the permanent collection

- Best time to visit: afternoons or late mornings to avoid school groups, or during the summer after school’s out.

2.8. Il Labirinto – Via Solari 35

The work

The Labyrinth is one of Arnaldo Pomodoro’s most complex and immersive works, an underground environment of approximately 170 square meters, designed in 1995 and finally brought to permanent public access through guided visits beginning March 17, 2025.

The work is currently located beneath the FENDI showroom at Via Solari 35, in the hypogeal spaces of the former Riva Calzoni industrial building. This very site once housed the Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro, and its layered history — industrial, artistic, institutional — echoes the very themes Pomodoro explored through the labyrinth: memory, matter, and metamorphosis.

The Labirinto unfolds through a succession of bronze-clad corridors, niches, and thresholds, all densely engraved with mysterious marks, glyphs, and structural abstractions. Visitors do not simply view the artwork—they are absorbed into it. Moving through the dimly lit passages becomes a tactile and psychological experience, where surface is not a boundary but a language.

The context

Though it no longer serves as the seat of the Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro, the site at Via Solari retains its central importance in the sculptor’s legacy. Hidden below the sleek retail spaces of the FENDI showroom, the Labyrinth survives as a secret heart of the city, a testament to Pomodoro’s desire to embed art in the fabric of life: unseen but resonant, silent but monumental. Its current hosting arrangement reflects the transformation of Milan itself: from post-industrial terrain to cultural capital, from archive to luxury. Yet far from diminishing the meaning of the work, this context sharpens its symbolism. To descend into the Labyrinth is to move against the surface logic of commerce, into a zone where time, history, and myth collapse and converge.

Tips for the Visit

- Location: Via Solari 35, Milano – Underground level of the FENDI showroom;

- Access: available via guided tours by reservation starting from March 17, 2025; tours typically last 45–60 minutes;

- Booking: reservations required via the Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro website.

2.8. Spear of Light – Conservatory

Thanks to one of my followers over on Instagram for this addition: I thought it was a temporary installation, but it looks like it’s still there. I’m talking about the gorgeous spear installed in the courtyard of our local conservatorium (via Conservatorio 12).

According to the official entry in the Foundation’s catalogue:

“Lance of Light is a work designed in reference to foundry work, with the light and absolute idea of a monumental element with a triangular cross-section, like an obelisk pointing upwards, a modern signal from the street or from the sky, with its strong call of light. In the sculpture one can read, as it were, the industrial history from the treatment of iron with its debris to the melting of steel and the operations on the incandescent material: a metaphor for human invention and the development of all research.“

2.8. Monumento Goglio – Monumental Cemetery

Another entry, thanks to one of my Instagram followers (I had completely forgotten about this one): the Monumento Goglio is situated in Riparto XII, Garden 88 of the Monumental Cemetery, a stunningly artistic place of remembrance here in the centre of Milan.

It was developed between 1969 and 1974, and it’s a stunning piece: the sphere is opened, and so is the tombstone, as if the sphere cracked it while falling from the sky… or the guest is waking up from their nap.

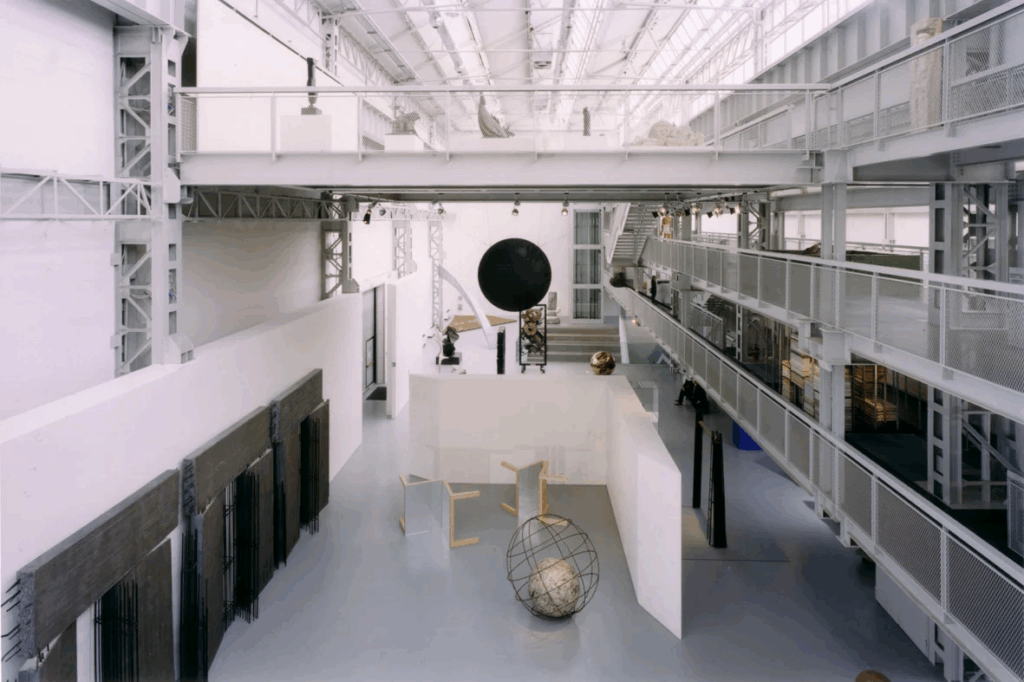

2.9. Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro – Via Vigevano

The Institution

Founded in 1995 by Arnaldo Pomodoro himself, the Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro is not only a centre for the preservation of the artist’s work but a dynamic hub for contemporary sculpture, critical discourse, and curatorial experimentation. Located at Via Vigevano, near the Porta Genova station in Milan’s vibrant Navigli district where I live, the Foundation serves as both a physical and intellectual home for Pomodoro’s enduring artistic vision.

Originally it was housed in the vast undergrounds of the Riva Calzoni industrial site on Via Solari — where we have seen his monumental Labirinto — the Foundation moved to its current headquarters in the early 2010s. From this new base, it has expanded its public and educational mission, curating exhibitions, publishing monographs, and developing programs that support emerging artists and critical thinking in the field of contemporary sculpture.

The Fondazione is structured around three core functions:

- Exhibition Space: regular exhibitions explore both Pomodoro’s oeuvre and that of other national and international artists. These shows often emphasise process over product, highlighting maquettes, sketches, and archival materials alongside finished works.

- Archive and Documentation: the Foundation houses Pomodoro’s personal archive, including letters, design drawings, stage sets, and correspondence with leading artists and architects of the 20th century. Researchers can access these materials by appointment, making the Fondazione a crucial resource for those studying Italian modernism, public art, and sculpture.

- Public Programs and Education: the Fondazione organises workshops, lectures, and outreach initiatives for schools and the general public. Its mission is not just to preserve the past, but to nurture the future of artistic inquiry.

While the Foundation houses works by Pomodoro, it does not function as a traditional monographic museum. Instead, it reflects the artist’s belief in art as conversation, not conservation. The curatorial program often pairs Pomodoro’s works with those of other artists, creating intergenerational and interdisciplinary dialogues.

Notably, the Foundation continues to manage and coordinate visits to key Pomodoro installations throughout Milan, including the Labirinto at Via Solari and sculptural works held in institutions and public collections. As such, it acts as both a cultural anchor and an activator of urban memory.

Tips for the Visit

- Location: Via Vigevano 9, Milano (close to Porta Genova FS and the Navigli canals);

- Access: entry is usually free for the main gallery; events and guided visits (including to the Labirinto) require online booking;

- Best time to visit: during exhibitions or scheduled talks; check the official Fondazione website for programming

Do you know of any other landmark? Let us know. The article is also published as a storymap on Esri’s portal.

No Comments