I can bear a little Picasso if I could stand Rodin last season, but it might be irksome to some of us, attending an exhibition on Picasso that’s particularly related to his “primitivism” period: the man was an asshole to women, and his fetishized approach to the female body extended to a consistent exploitation of African aesthetics and culture. Or, did it?

According to the curators of this exhibition, the new grand installation at the MUDEC here in Milan, Picasso’s approach can’t be compared to the blind exoticism other artists experienced, as he was equally fascinated by African art and Neolithic pieces, from Proto-Iberian examples of pre-Roman Spain and from Oceanic art, from ancient Egyptian figures and the figures from the black vases of classical Greece.

Picasso invented transpositions, reshaped figures with disproportionate volumes, generating a constant metamorphosis of figures that was often characterised by a strong erotic connotation, and that guided the evolution of his painting and sculpture, especially in times of personal or social crisis.

And again, carrying on in the words of the curators on the exhibition leaflet, he “always showed profound respect for the artistic manifestations of other cultures and times. More than any artist of his generation, he had the ability to understand and reinvent these artistic expressions with the noble aim of giving impulse and a new path of exploration to universal art.”

For Picasso, the art that inspired his work, that moved his creative mind in an unstoppable desire to break new ground, was not ‘primitive’. There is no ‘before’ or ‘after’ in art, there is no ‘other’ or ‘different’ art: Picasso conceived art as a timeless Whole. “There is neither past nor future in art. – he loved to emphasise – If a work of art cannot always live in the present, it has no meaning”.

You can agree or disagree, and many historians of art disagree with this approach, as a matter of fact, stressing how exploitation is to be judged by the results and by the lack of effort to level the playing field: we have no record of Picasso using his influence to help African artists to emerge, and a testimony of that is the comparison of African culture (very much alive) with pre-Roman Hiberian people (very much dead). One small museum such as the Picasso Museum in Paris recently reshaped its own entire fucking exhibition to make space for the discourse.

“We wanted to open up the museum, reach a wider audience and bring in all those debates: on women, post-colonial issues and politics. Bringing in new and contemporary artists shows that we’re open to all the debates on Picasso. We put these questions on the table and discuss them without claiming to have all the answers. We wanted to make Picasso relevant.”

— Cécile Debray, president of the Picasso Museum in Paris

The exhibition seems to draw a lot from this reshaping of the Paris museum, starting from the aesthetic audacity of wallpapers that in Paris have been handpicked by a rather anxious Paul Smith, and resulting in one final room that directly draws from the Imaginary Journeys room in Paris. Unfortunately, the comparisons stop there.

An Exhibition with No Questions

(and all the answers)

In its address of how Picasso employed African concepts and shapes, the Mudec exhibition starts with the bold statement that “Pablo Picasso always showed profound respect for the artistic manifestations of other cultures and times” and that “More than any artist of his generation, he had the ability to understand and reinvent these artistic expressions with the noble aim of giving impulse and a new path of exploration to universal art.”

Though I very much prefer the open approach of the Paris Museum, I understand that the former is a stage while a temporary exhibition is a show, and I take no issues with the curators having such a strong and definitive answer to such a complex and compelling question such as: “Was Picasso a racist asshole?”. Even if the answer is one I don’t agree with.

What I do take issue with is the lack of any deeper expansion on the topic beyond the initial statement.

As if we’re supposed to take their word for it, the curators take us through a selection of art and artefacts, without any explained correlation between them, and ultimately don’t bother explaining how Picasso gained this “deeper understanding” of African values and why should we consider him different than other contemporaries who engaged in similar contaminations appropriations.

Introduction: a chronological approach

The introductory room, a stunningly installed display of giant pictures showing Picasso and his studies, surrounded by antiquities and ransacked African artefacts, takes a chronological approach, detailing how Paris in the early years of the 20th century was the place where contemporary art was emerging, both in opposition to the academic tradition and in continuity with it.

Young Picasso was starting to move his artistic first steps into this environment: Cézanne showed him how to reinterpret volumes, but his visit to the Musée du Louvre was going to be much more influential, directing him towards a rediscovery of shapes from Iberian art, Egyptian archaeology and Greek vases.

If you’re interested in this particular aspect, the Louvre itself held an exhibition a while ago, called “Les Louvre de Pablo Picasso”, and selected the masterpieces that might have been particularly influential for the artist. One episode stands out:

Things started off with a bang. In 1911, the affair of the theft of the Mona Lisa broke out, an act that Géry Piéret (1884–1918 ?), the former secretary of the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, wrongly boasted of having carried out. However, four years earlier, he had stolen from the Louvre two Iberian statuettes: one was sold to Picasso, the other given to him. Panicked by the announcement of the theft of the Mona Lisa, Apollinaire and Picasso decided to give back the statuettes anonymously via the offices of the Paris-Journal. Suspected of complicity in the theft, Apollinaire was locked up for a few days, and Picasso was questioned before both of them were finally found to be innocent.

If you still have doubts about Picasso’s morality, there’s literally nothing else I can tell you. Or maybe there is.

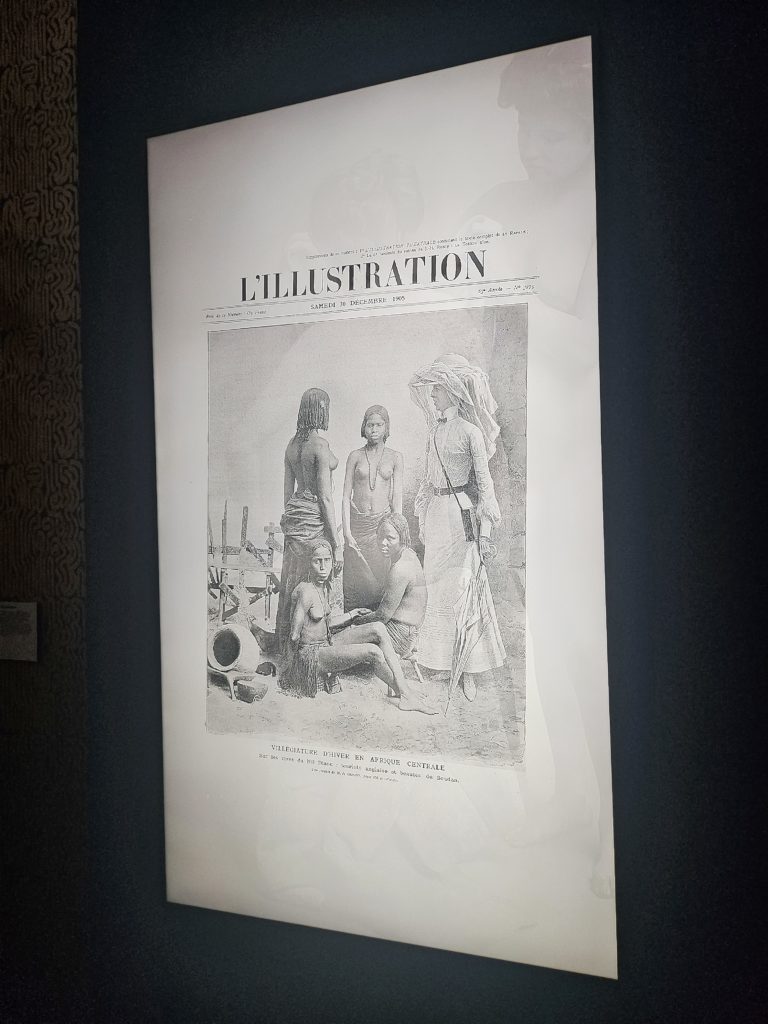

At the Trocadéro Museum, inaugurated in 1907, the works of art from the various African cultures and the Pacific cultures that we had just started harassing had a strong impact on the young, white painter in need of inspiration. It’s worth mentioning, though the exhibition doesn’t give us any comparative timeline between Picasso’s artistic exploits and colonialism, that 1907 had also been the year of the infamous Colonial Exhibition, the fourth colonial exhibition organized in France. The “show” was set up at the Tropical Agronomy Garden of Paris, and allegedly was aimed at advising the settlers of the colonies on agricultural groundbreaking methods (pun intended), but had the charming addition of “human zoos”. Yes, you heard me right. Villages from Indochina, Madagascar and Congo, Sudan, Tunisia and Morocco were reconstructed for the Parisian’s amusement, and what’s a village without villagers? Indigenous people were brought in from their homelands throughout the French Empire, under contract and salary, and employed to animate these villages under scripts that were written to convey French cultural superiority.

The colonial garden kept running through the whole First World War.

You can read more about it here.

There’s no question of Picasso comparing African artefacts to archaeological exhibits because he didn’t know the cultural realities they came from, though I do not know the extent of his indulgence in the personal fetish towards actual indigenous people.

According to the curators, he understood the animist significance of those objects, and how they were designed to link people to the spirits of nature or to evoke the souls of ancestors back to present life.

[This] made him realise that the mission of art was not a simple representation of reality, nor the simple pursuit of beauty. Ineluctably predestined to change the course of art history, Picasso immersed himself in a universe of exotic influences.

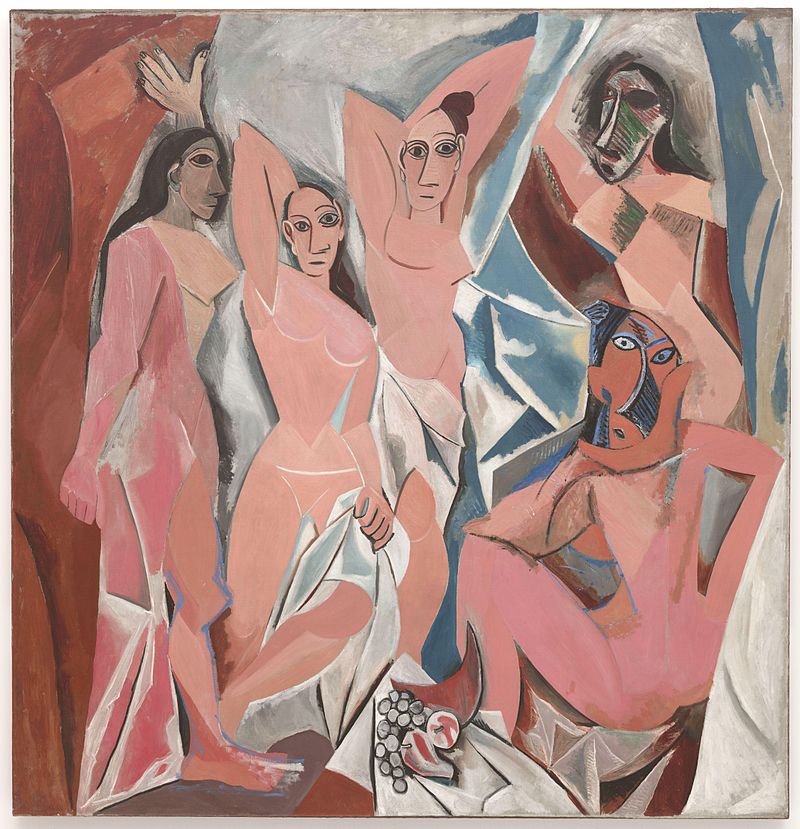

In those objects from distant and exotic latitudes he also discovered a formal freedom that allowed him to overcome traditional barriers and create his first great cubist work, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

And to the demoiselles — never presented even in a reproduction because what are you doing in a museum if you don’t know the art already? — is dedicated the central section of the exhibition, proudly showcasing one of Picasso’s preparatory sketchbooks to illustrate the process of transformation that the title calls “metamorphosis of the figure”, cleverly distracting us from the central question of why are we looking at a bunch of white women striking a pose in African masks.

Going back to the Mudc exhibition, you’ll find it’s divided into five sections:

- The first introduces his early years of research, in which Picasso collected objects from “primitive arts”, and it’s comprised of a small juxtaposition of objects and sketches;

- the second is dedicated to the creative process of the Demoiselles d’Avignon;

- the third is a full-on Cubist section;

- the fourth is dedicated to the persistence of “primitive” aesthetics in the continuation of his career;

- the fifth attempts to close the circle around the concept of the “metamorphosis of the figure”.

A last section brings us back to the topic of actual African art.

Are you ready?

1. The early years

From 1904, when Picasso eventually settled in Paris, his art underwent a rapid evolution due to new friendships and the discovery of art forms from different latitudes and eras.

Picasso hunts for aesthetic novelties, for new ways of perceiving lines and volumes, and the cosmopolitanism of Paris provides fuel for his research with its artistic avant-gardes, his historical richness and his rampaging colonialism.

In the spring of 1906, during one of his numerous visits to the Louvre, he discovered the Cabinet Ibérique, showcasing numerous sculptures found in Andalusia. A dedicated exhibition on this influential relationship, perhaps the least controversial of his career, was curated by Cécile Godefroy in a joint effort between the Picasso Museum in Paris and the Botin Centre and explored the influence of Iberian art in the work of Picasso through more than 200 works. Findings such as the Cerro de los Santos or the Lady of Elcheled him to create several works over the following months – preparatory drawings, sculptures and paintings – directly influenced by this monumental stone statuary and the small bronze ex-votos that he contemplated during his visits to the museum.

Picasso’s Iberianism is today recognised as a fundamental step towards objective and conceptual representation, and five of these bronze idols are shown at the exhibition in Milan.

The section immediately follows up with some photographs and postcards, with the disclaimer that some of its content might be disturbing for a part of the audience. I bet they’re referring to the presence of female nudity.

2. Sketches for the Demoiselles

Picasso quickly abandons the Iberian references to adopt the order, harmony, rhythm, plastic purity and naked ladies offered by “tribal art”. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (originally titled The Brothel of Avignon, in case you have any doubt about the sexualization of the topic) was painted in 1907, the same year of the Trocadéro inauguration and the infamous Colonial exhibition, and traditionally inaugurates the co-called “African period” of his production, flanked by Nu à la draperie, later called La danse aux voiles, another painting the exhibition mentions but can’t be bothered to show you.

Picasso himself, talking about his visit to the Trocadéro Museum, would later say: “In that moment, I understood the profound meaning of painting [and] I understood why I was a painter”.

I’m sure indigenous people were thrilled to have their heritage stolen and destroyed for your amusement and artistic growth.

African art provided Picasso with a new idea of beauty, far removed from both illusionistic reproduction and all imitative art form based on direct representation, a “transposition of appearances”.

In short, 1907 sees a Picasso who needs to find new tools to delve into the depths of the avant-garde.

This exploration is originally based on the observation of the Western tradition of Ingres and Cézanne but turns to ancient and non-European cultures regardless. Iberian art, archaic Greece, Egyptian art and African and Oceanic art determine the extraordinary diversity of styles in the drawings that accompany the Demoiselles d’Avignon, a stunning amount of preparatory works indeed. The notebooks that bring together most of these studies constitute a kind of visual diary.

The preparatory studies of the notebook are paired with simple figures sketched in colour that fed on the shapes of the reliquaries of the Kota people, as the Colourful Indian Head and Sad Head, with a White Face, both from 1907 and both in the exhibition.

The large number of notebooks containing preparatory drawings for Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, fifteen in total, makes it possible to establish the chronology of the work’s genesis.

Picasso worked on the large composition between the winter of 1906 and the summer of 1907, and the notebooks attest to his compositional research, his initial effort to assimilate the geometrism of Cézanne and the plastic contributions of Iberian, African and Oceanian sculpture.

The majority of the drawings contained in these notebooks are compositional studies, where he explores the reduction of the number of figures from the initial seven to the final five, studies of the individual women taken from various angles, isolated studies in geometry and perspective.

3. Cubism

Picasso’s Cubism broke away from Braque’s landscapes shown at L’Estaque in 1908 and dubbed “cubist” by Matisse, in the midst of Louis Vauxcelles’ criticism of this style in 1909. The reflection on Cézanne and the Iberian and tribal arts leads Picasso to explore the form more than the apace, and the way these forms impact the space surrounding them.

Between 1907 and 1908 Picasso works to bring together his Western models (Ingres and Cézanne for instance), and the primeval geometry he finds in Iberian and African art, particularly the magical functions and formal beauty he sees in masks and statues. This leads to a new art, totally alien to Western conception, though his painting continues the tradition of exploring deliberately banal subjects.

Between 1909 and 1911, in close complicity with his fellow in crime Georges Braque, Picasso explored a new space through landscapes, figures and still lives.

Picasso and Braque reduced everything to a pure object of formal speculation, they fragmented the elements into facets, uniformed by a sober chromatism, escaping from mimetic figuration.

Trying to bfeak aay from tradition, they both tried to go beyond the bourgeois model of painting and approached the crafting of objects and masks with objects, sheets of newspaper, wallpaper and cardboard; these same materials sill end up in their paintings, resulting in what we know as ‘collage’.

Yvan Goll: a pleasant intruder

Though its presence in the exhibition is scantly explained, I was happy to find Yvan Goll’s Faun Masks.

Goll, pseudonym of Isaac Lang, was an expressionist and surrealist close to both the French and the German movements. He settled in Paris in 1919 with the German writer and journalist Klara Aischmann, later Claire Goll, whom he married in 1921. In Paris he wrote surrealist dramas and film scenarios with contaminations of fantasy and mundane, and a strikingly expressionist energy, such as Mathusalem. Marc Chagall illustrated a collection of love poems by the Golls, and Picasso illustrated his Élégie d’Ihpetonga suivi des masques de cendre (Elegy of Ihpetonga and Masks of Ashes) in 1949.

Dedicated to Picasso himself, the first part of the work reflects on New York and on Goll’s own experience of the place between 1939 and 1947. Ihpetonga means “high cliff”, and it was the name given by the Canarsie Lenape to that part of Brooklyn overlooking the port of New York.

Goll’s poem contrasts the infernal city with incantations of an Indian Squaw banished from her land, whose totems wreak a terrible vengence.

The second part, the Masques de Cendre, are seven love poems dedicated to Goll’s wife Claire.

Where are the fauns, you ask? Well, nowhere. Faced with the opportunity of making illustrations of the Canarsie’s totems in a story of appropriation featuring a native woman, Picasso decides to go all Weterner on it, and designs horned fauns. He calls them The Four Faces Of the Devil, and they’re lithographs from April 11, 1949.

4. Beyond Cubism

Picasso’s latest stage in this exploration of the figure as inspired by African and Hiberian culminatez in two paintings: The Three Dancers and The Kiss, both from 1925.

The Three Dancers, which the exhibition repeatedly calls The Dance for reasons I don’t know, is a paint with surrealist influences, allegedly painted after a trip to Monte Carlo with ballet dancer Olga Khokhlova who was Piasso’s wife back in the days. Scholars have been tried for centuries to identify the figures knotted together in what has been described a dance macabre: the one on the left, with her head bent backwards in an impossible position and an exuberant sexuality, is considered to be Pichot’s wife Germaine Gargallo with the one in the centre being Germaine’s former lover Carlos Casagemas, also Picasso’s friend. The one on the right, swallowed in darkness, is usually identified as Ramon Pichot, also a friend of Picasso who died right before he painted this work.

Casagemas was also dead, though this might be a bit of an understatement: he shot himself twenty-five years before, after failing to kill Germaine. The love triangle becomes a tangle of ghosts, with Germaine being depicted with bared teeth and a red mouth like a vampire, and the two mn stuck like martyrs or pulled like puppets. Picasso had been a lover of Germaine too, which adds the hypocrisy to the mysoginy.

The explosions of disjointed forms loosely pieced together and the plastic exaggerations obey both cubism and surrealism, and the same happens for the other 1925 work, The Kiss.

To contexualize this work, one should rememr that the Surrealism Manifesto had appeared just the previous year and André Breton, leader of the group, paid homage to the pioneering role of Picasso in his article “Surrealism and Painting”. Regardless of that, he Picasso Museum itself doesn’t hesitate to define “confusing” the tangled shapes and strident colors of this painting.

Oceanian adornments and masks with bright colors and undulating shapes are found here in the flat areas of pink, blue, green, yellow, white, delimited by a thick black circle and with almost x-ray patterns, which reveal bodies blending together even in fusion.

You can barely distinguish the man’s arms encircling the woman’s body, her feet with their toes spread apart, the single conjoined mouth, and their facial features being replaced by genitals.

The use of these metamorphoses becomes more frequent between 1926 and 1927 in parallel with Picasso’s interest in tribal and Neolithic art and the plastic reflections initiated by Joan Miró. Picasso keeps creating anatomical transpositions, remodelling with a strong erotic component, following the idea that the concept of absolute beauty is sterile and that there is no beauty without ugliness. The interchangeability between human faces and sexual organs appears throughout all his work.

While he depicts organic, he also draws geometric, angular, rigorous and rational forms; He takes these metamorphoses very far, unlike the Surrealists, but achieves the dissociation of lines, volumes and colours though keeping to the plane of reality, without addressing the themes of dreams or the unconscious. Though the man clearly needed professional help, he never delves into the psychoanalytic realms of dream and the subconscious if not for few, isolated incidents.

The most beautiful piece of the exhibition, and perhaps the only truly remarkable on, is ths stunning Nu dormant from 1954, where the woman is both stretching with her arms bent backwards and crouching on the side with both hands beneath her head. The delicate movement capturing the intimacy of her sleep, an intimacy that for once is not sexualized, the sharp contrast between her skin and the black outline of a face that’s almost a mask, and the overall opacque feeling really wash your mouth of some of the unpleasantness seen through the exhibition.

The Last Section

That is, until you reach the last section.

Up until, now, the exhibition had deviated from the preme and started talking about the human figure, and you had almost forgotten about the underlying problem: the exploitation of African art.

While Picasso’s attraction to traditional African art is well known, the importance that contemporary African artists attach to the Andalusian artist should also be highlighted. By way of example, the works exhibited by artists such as the Beninese Romuald Hazoumé, the Mozambican Gonçalo Mabunda and the Congolese Chéri Samba demonstrate the recognition of Picasso as the main interpreter of the expressive foundations of the African continent.

Silly me, I though the main interpreter of one’s culture should come from that culture.

The last room in the exhibition directly draws from what the Picasso museum has done in Paris with the Imaginary Journeys room, even borrowing and displaying a rather explicit criticism by Chéri Samba of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, who paints an old Picasso with swolen fingers under the writing “Quant il n’y avait plus rien d’autre que… l’Afrique restait une pensee.”

When there was nothing left but… Africa remained a thought.

The work is part of a series on the oppression of African artists and you can rea moe about it here.

And it’s precisely Samba’s point of view that might provide a better lense to understand the connection between Picasso and the African art landscape, more than the curator’s boasting of how many Picasso exhibitions have been held in Africa. “But what is this? Isn’t this injustice? Why do they refuse the work of Africans, and yet continue to present the same work (the mask)?”

Can you really say that Picasso was a racist asshole, if you want to be respected in the art landscape? Malén Gual and Ricardo Ostalé just demonstrated you can’t.

1 Comment

Pingback:Picasso the Foreigner – Shelidon

Posted at 12:14h, 17 November[…] you remember from the last time I talked about him, I’m not overly fond of Picasso as a man. I can’t get over his attitude towards women […]