Let me start with one simple but fundamental assumption: I hate Rodin. Not artistically, of course, but I think he was a sick piece of shit and a bastard through and through, who used women, abused Camille Claudel both emotionally and artistically, stole her stuff, and up to these days we still say she “died of consumption” after “falling into paranoia”.

Paranoia my ass.

Anyway.

The exhibition is hosted at the MUDEC, Milan’s Museum of Cultures, and springs from a collaboration with Musée Rodin in Paris, which lent 52 pieces. Don’t expect the usual exhibition, though: the project unfolds across three sections and they’re respectively curated by Aude Chevalier, Assistant Curator of the sculpture department at Musée Rodin itself, Cristiana Natali, Professor of South Asian Anthropology, Anthropology of Dance and Ethnographic Research Methodologies at the University of Bologna, and Elena Cervellati, Associate Professor of History of Dance and Dance Theories and Practices at the Department of Arts of the University of Bologna.

The exhibition also becomes an opportunity to take an extraordinary journey into the world of dance through a video selection referring to contemporary choreography and choreographers, who were inspired by Rodin for their performances. The continuous dialogue between Rodin’s sculptures and the multimedia and digital system, together with the immersive installation create a constant play of visual and symbolic cross-references.

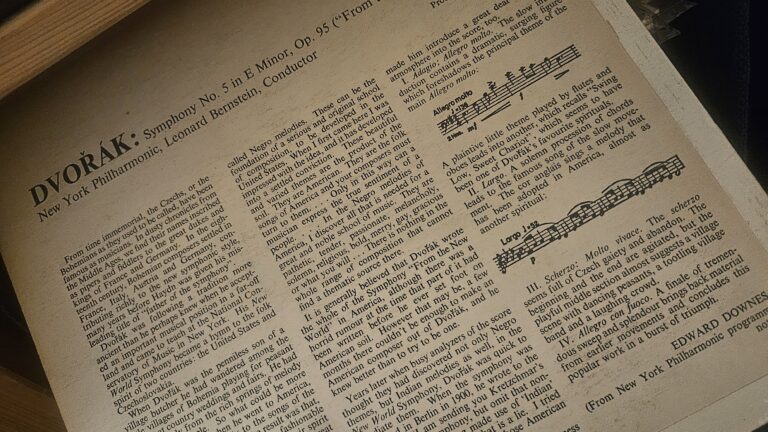

Rodin and Dance: a timeline

At the beginning of the XX Century, Paris was at the centre of the artistic avant-garde, and this included painting, sculpture but also acting and dancing. Mobility was facilitated by the expansion of railroads, and sea transports were becoming safer, or at least less distressing, so people would come to Paris searching for fortune and they would cross their path with touring artists. Though Wolfgang A Mozart was possibly the first one to go on tour when he was a child, and even if historians attribute to Franz Liszt the first idea of concert tours, it’s undeniable that the phenomenon boomed at the beginning of 1900.

Rodin’s studio was a well-known meeting place for intellectual and artistic circles, and this included visiting dancers. The exhibition opens with a timeline, on the usual curved glass walls in the museum’s foyer, the lower part of which focuses on Rodin himself and with an upper part concentrating on the history of dance.

“In our art, the illusion of life is achieved by good modelling and movement.”

– Rodin to Paul Gsell (1911)

Rodin and dancers

Rodin was attracted to both avant-garde shows, especially the ones in which the dancer was female and nude, but he showed as much interest in classical ballets as in French or foreign folk dances. The first room starts with a selection of these dancers.

Loïe Fuller (1862 – 1928)

American, a pioneer of modern dance and theatrical lighting techniques, she had debuted as a toddler in Chicago, performing in dance roles just as much as dramatic performances. She exhibited in groundbreaking free dance shows, alongside Isadora Duncan and Ruth St. Denis, and developed her own movements breaking free from the figures of traditional classical dance. Her improvisation techniques involved experimenting with garments such as a long skirt or a shawl, which served as a choreography prompt and which the dancer used to play with the ways it could reflect light. These experiments led to her invention of the Serpentine Dance, in 1891, a free dance show with silk costumes illuminated by multi-coloured lighting she designed herself. This dance fascinated early filmmakers: both the Lumière brothers and Méliès filmed short takes of dancers twirling their coloured skirts.

Rodin saw her performing at the Follies Bergère between 1892 and 1893, but the two artists met in person in the summer of 1898, through their mutual friend Roger Marx, a cultural critic and fierce supporter of both. According to sources close to Rodin, it was Fuller who actively sought out the sculpture and asked to model for him. Other sources indicate that both artists admired each other’s creations and wanted to establish a connection.

In any case, Rodin was open to the idea of creating a statue based on Fuller’s movements and arts, but the dancer was either too busy or on the move and, though she expressed interest in having the statue done by the Exposition Universelle in 1900 in Paris, where she was giving performances, Rodin never undertook the work.

Fuller eventually established herself in a theatre of her own, and remained friends with the sculptor: she introduced him to other dancers such as Japanese dancer Sada Yacco, who practised a Kabuki-inspired dance style and was so tremendously popular in France that, upon returning to Japan, the local government allowed her to be the first woman to perform a dance on stage since the practice had been outlawed.

Though Fuller could rarely see Rodin due to his peculiar romantic choices, it’s speculated that he inspired her “The Dance of Hands”, which debuted at the Metropolitan Opera House in 1908. We know for a fact that he gifted her a moulding of his hands sculpture.

This contemporary photograph of Fullers hands is preserved at the Rodin museum and displayed in room 1.

“The soul expresses itself through each and every part of the human form. A hand separated from the body can express its joy, its sorrow, its grief, with as great perfection as the complete form of man.”

Ruth Saint-Denis (1879 – 1968)

Another American pioneer of modern dance, she’s mostly known for Eastern inspirations and her interest in dance as a mystic form of expression. In 1915, she founded the American Denishawn School of Dancing and Related Arts.

Rodin depicted her in a sketch, or, at least, he represented her uplifted torso and outstretched arms.

Hisa Ōta (1868 – 1945)

Known by the name Hanako, the twice-divorced Geisha started touring Europe in 1904 and arrived in Paris in 1906, when she met Rodin. She returned to Japan in 1916, to recruit more dancers, and toured Europe until she returned to Japan for good in 1921.

One of her most famous performances involved her interpretation of a suicide, and it impressed Rodin so much that he sculpted her face in multiple masks. He donated her two of them she brought with her in Japan.

This is how Rodin’s biographer remembers her session:

Hanako did not pose like the other models. Her features were contracted into an expression of cold, terrible anger. She had the look of a tiger, an expression completely foreign to us Occidentals. Using the force of will with which the Japanese confront death, Hanako was able to hold this expression for hours.

Darling, you’ve never seen a woman this angry because “us Occidentals” lock them into an asylum to wither and die.

This variant of the mask is preserved at the MOMA.

Carmen Damedoz (1890 – 1964)

If you’re thinking “Oh, like the aviator?” I’ll have to stop you immediately: she is the aviator.

She was born in Paris from a French family, and adopted the Hispanic-sounding pseudonym to complement her natural complexion. She modelled for many artists, including Alberto Giacometti, and we have some flaming letters that might suggest an affair between her and Rodin. Jean-Francis Auburtin painted her several times, almost always from the back

She became a pilot in 1913.

Jean-Francis Auburtin, Carmen Damedoz (model of Rodin)

Isadora Duncan (1878 – 1927)

It would take me a book to summarize her importance, and I have neither the time nor the preparation to do it. Suffice it to say that she was born in American and lived as a complete and utter legend throughout Europe, the US and Soviet Russia.

She was a non-conformist from the start, taking inspiration from everything that was not classical dance: she looked at Greek vases and bas-reliefs in the British Museum while in London, danced in the salons of Marguerite de Saint-Marceaux and Princesse Edmond de Polignac while in Paris and eventually started touring with Loïe Fuller and they experimented together, receiving mixed reactions from critics which meant they were doing things right.

“[She] has this gift of gesture in a very high degree. Let the reader study her dancing, if possible in private than in public, and learn the superb ‘unconsciousness’ – which is magical consciousness – with which she suits the action to the melody.”

– A. Crowley on Duncan’s dancing (whom he called “Lavinia King”)

She became known for her eccentric acquaintances and her participation in extravagant avant-guards, such as the 1911 party thrown by the French fashion designer Paul Poiret, who rented a mansion and re-created La fête de Bacchus, the Bacchanalia hosted by Louis XIV at Versailles.

Despite these occurrences, she disliked money and thought it tainted her primary vocations: creating beauty and teaching. She opened her first school 1904, in Berlin, and it was a philosophy school where young women could approach her idea of dance: it became the birthplace of the so-called “Isadorables”, Duncan’s protégées.

Her figure and personality inspired Rodin to create a marble sculpture called Ève au rocher, Eve on a Rock, from 1905-1906. We think he had seen and talked to her during a jeune danseuse where he was invited by his friend, the symbolist artist Eugène Carrière, who also painted Duncan in a ghostly portrait from 1910. When Rodin was offered the Légion d’honneur in 1903, many of his friends threw him a lavish party in Vézely, and Duncan performed for the occasion.

Cambodian Dancers

Colonialism put up a show of itself around the second half of the 19th century, with the birth of the so-called International and Universal Exhibitions, the first of which took place in London in 1851. These events attracted tens of millions of visitors, and allowed the various nations to present industrial and technical innovations as well as some of their intellectual and artistic productions, but the participation was limited to a certain set of Countries. Peculiar, for a thing called “Universal”.

Colonial Exhibitions were organised in the same period, inviting various European nations to put on display the products from their colonies and the people they were destroying, subjugating and killing over there.

Among the initiatives of the Universal Exhibition of 1889, Rodin saw the performance of a troupe of Javanese male and female dancers from the city of Solo (Surakarta), who were performing in Paris for the first time on that occasion. The sculptor’s presence in the audience is proven by some sketches preserved at the Musée Rodin. The effect of this discovery, however, was nothing like the one produced on him in 1906 by the Cambodian dancers.

Sisowath, the King of Cambodia, and his daughter Princess Symphady, had travelled to Paris that year, accompanied by some members of their court and seventy dancers.

Rodin first saw them at two special performances offered in Paris and then again at the Colonial Exhibition in Marseilles, in 1906 when he would also meet Hanako, and was thunderstruck.

“the enchantment of my life… dancing figures in marble conceived by Michelangelo…’.

Alda Moreno (1880 – 1963)

We know very little of Alda’s life. What we know is that, in June 1812, Rodin’s patron and collector Count Henry Kessler was shown some of Rodin’s studies and defined her as:

“a very supple, girl, a kind of acrobat, whose poses provide all kind of entirely new and bizarre arabesques.”

She worked an acrobat and modelled nude for him through 1903, until she disappeared in 1905. She was having an affair with one of Rodin’s friends, though I wasn’t able to find out with whom.

Rodin searched for her everywhere, as she wanted her to model for him again: eventually, a friend saw her nude photographs in the November issue of Le Nu académique. He was able to track her down, and convinced her to model for him again: from this series of works, Rodin drew his series “the creation of woman”.

To him, her poses were “something like the stages of an evolution, transitions leading from the animal world to woman”.

Rodin kept these works very secret, and they were only recently discovered.

Adorée Villany (1888 – 1920)

The last dancer of the selection, she’s even more mysterious than the previous: we don’t know her birthplace, we don’t know her real name and we can only guess her birth year.

The first account we have of her comes from The Grazer Volksblatt newspaper in 1911, stating she was performing in the Berlin Überbrettl cabaret as “Duncan imitator.” She performed her own version of the Dance of the Seven Veils while reciting the tragic woman’s last monologue as written in Oscar Wilde’s Salome, and her performances incorporated themes from paintings by contemporary artists such as Franz Stuck and Arnold Böcklin. She was her own choreographer, designer, trainer. She used to appear unclothed and was prosecuted twice, and acquitted in Munich where the jury stated her performances were a work of art.

The dancer is shown, nude and performing, in a picture taken in Rodin’s atelier while she sports a hairstyle from a Greek vase.

Rodin’s Works

The works showcased in the centre of this room are a set of clay figures, which Rodin used to sculpt and then dismember, reattaching pieces and torsos back again in new poses.

On the background on the left, photographs and details from the dancers show us some of his inspirations: Ruth St Denis in yogi position, Loïe Fuller‘s hands (I swear to God I could fall in love with these hands), the naked picture of Adorée Villany, and Carmen Damedoz dancing with a shawl.

The centre portion is made of sketches, through which Rodin tried to encapsulate the most complicated vibrations of a dance, and in between we can see a chalk sculpture, Study for Iris, from around 1892. This doesn’t differ much from the bronze he will make 1895, called Iris, Messenger of the Gods, also known by less mythological names such as Flying Figure, or Eternal Tunnel. It was a part of Rodin’s second (and second-time failed) for a monument to Victor Hugo outside the Panthéon in Paris, a monument he envisioned as a sculpture of the writer being accompanied by three female figures representing Young Age, Maturity and Old Age. Iris was neither of them, but a fourth figure personifying glory, of the spirit of his age, hovering over Hugo’s statue. Too bad that glory, at least in Rodin’s idea, had her legs spread, her right hand clasping her right foot, and a crude depiction of her genitalia for everyone to admire.

On the other side, other sculptures complete the room, with smaller clay studies and an audio-video installation.

The Red Room: Cambodia, Japan and Other Horizons

The room hosts some of the sketches the artist made when he saw the Javanese dancers, and a central piece showcasing some pieces — both original and made by Western — to signify the tremendous impact that these touring oriental shows had on the imagination of Rodin’s contemporaries.

His drawings have a futurist quality to them (the Manifesto of Futurism was published in 1909) and capture motion more than form, often exaggerating fingers and curves to highlight a certain movement, a particular vibration.

On the walls, works by contemporary artists are displayed as videos or pictures of performers posing with Rodin’s statue in Paris.

Alessandra Cristiani

She’s the author of a trilogy of performing pieces called The Question of the Body and the Art of Egon Schiele, Francis Bacon, Auguste Rodin, each of which explores a different aspect of the tormented art of this men through the use of her own body.

Corpus delicti – from Egon Schiele is the first piece and starts with the dancer dressed only in a scarf, a gift from her mentor Masaki Iwana. Starting with by a patter of rain, which soon becomes the roar of the elements, the dance expresses impulses of female eroticism contaminated by the passing years, sometimes yearnings for protection, other times laying derelict and abandoned to solitude after intercourse. The light flashes over disjointed limbs, highlighting bodies made of tense nerves, melted makeup and dishevelled hair as it happens in Schiele’s paintings.

Nucleo – from Francis Bacon starts with scenic elements such as a wine goblet, a wooden pallet with scattered photos, a chair, a large white vertical canvas: the dancer starts in slow potion and then picks up the pace, but we’re far from Schiele’s passions. She’s circumspect, astonished, terrified. The wine overflows, she shakes, while sounds of nature starts screaming in the background. The body is shattered.

Naturans – from Auguste Rodin is the last piece and we find ourselves in a workshop. We hear rollers scattering, electric saws, drills, chisels, hook knives. The performance is an act of birth where the raw materials are broken and bent to create a form, whether willing or unwillingly touched by the hands of the creator. Violence and abuse are at the centre of this performance each time the matter seems to be resisting, each time sounds torture the unwilling and contorted body of the dancer.

Julien Lestel

Rodin is one of the main shows ideated by Julien Lestel’s corp-de-dance, founded in 2007.

It’s a sensual show, marked by virtuosity and sensuality, without many of the tormented traits Cristiani explored so successfully: it proposes a new interpretation of Rodin’s personality where an intense physical dialogue takes place between the ancient idea of sculpture and matter, the mystery of substance and nature, carnal fantasies and a phantasmagoria of corpses that can be solitary or entangled, anchored to the ground or taking flight, afflicted or exultant, seductive or distressing.

One of the most obvious quotes of the show is from the Age of Bronze, also in the next room of the exhibition. More parallels and references can be seen here.

Elisabeth Schwartz

Dancer, choreographer and historian, Schwartz proposes a show made of corpses and matter called Jaillissements and dedicated to the sculptor’s relationship with Isadora Duncan. The choreographic composition is based on the aesthetic principles of Isadora Duncan’s dance as she would teach them in her school, and draws from the principles of Rudolf von Laban, a late XIX century dance artist, choreographer and dance theorist. The term “jaillissement” is French for sprout, gush, also used metaphorically as an explosion of ideas.

Florin Ion Firimitã

Florin Ion Firimitã is a Romanian-born visual artist and writer who has lived in the US since 1898. He worked on some stills where a model is shown in conversation with works from the Rodin Museum, and I can only show you a couple of them, but I urge you to go and see them for yourself. They’re featured here.

Julien Vallon

Another visual artist, he’s a photographer and filmmaker who mostly works on bodies. In the exhibition you will find some photographs, but I suggest you also check out his book with sketches and stills from his movie film inspired by the French sculptor.

Third Room: sculptures and contemporary choreography

As he himself explained, movement was inseparable in Rodin’s work from a constant concern to represent nature and what he perceived of it. Lending movement to his sculptures allowed him to represent the skin stretched over the muscles of the model in tension, allowed him to depict the “protrusions of internal volumes”, as he would put it.

In this room, alongside more videos of other performers, we find the Walking Man, The Bronze Age, and a stunning piece called The Toilet of Venus.

The Bronze Age, compared with a scene from the ballet by Julien Lestel.

Also referred to as The Bather, The Wave or The Awawkening, the Venus has great similarities with other works such as the Kneeling Fauness in the left half of the tympanum of the Gates of Hell. In this version, the head of the figure is leaning back and facing to the right, a posture that Rodin used to illustrate the poem Le Guignon (Evil Fate) by Charles Baudelaire in Les Fleurs du Mal.

To lift a weight so heavy,

Would take your courage, Sisyphus!

Although one’s heart is in the work,

Art is long and Time is short.

Far from famous sepulchers

Toward a lonely cemetery

My heart, like muffled drums,

Goes beating funeral marches.

Many a jewel lies buried

In darkness and oblivion,

Far, far away from picks and drills;

Many a flower regretfully

Exhales perfume soft as secrets

In a profound solitude.

Fourth Room: The Thinker

Because people would freak out if you held an exhibition on Rodin and didn’t feature a version of this guy, I guess.

The last room features three more videos from three more performers who were inspired by Rodin: Boris Eifman, Anna Halprin, and Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker. I’ll leave you with them in reverse order.

Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker

The performance was created at the invitation of the Beyeler Foundation in Riehen/Basel, Switzerland, for an exhibition called Rodin/Arp which was being held at the museum. The works of Auguste Rodin and Hans Arp are mixed in the movements as two attracting opposites: Rodin’s powerful obsession with the human body and its implicit narrative capacity is balanced by Arp’s desire for formal emancipation. The show is called Dark Red – Beyeler, possibly to highlight this duality.

Anna Halprin

Journey In Sensuality is more than a dance: it’s a movie and a documentary, an intimate account of the fusion of Halprin’s art with Rodin’s spirit. Directed by Ruedi Gerber, the movie shows us the dynamic bodies of modern dance engaged in conversation with the static statues. The performance is immersed in nature, but I had to bolt out of the room at the close-up of a naked dancer being bitten by mosquitoes. Sorry.

Boris Eifman

An absolutely stunning ballet called Rodin, Her Eternal Idol, is definitely my favourite, here, as it tells the story of Rodin with Camille Claudel, the unrecognised disciple who died in an asylum.

“The story of life and love of Auguste Rodin and Camille Claudel is an amazing tale about an incredibly dramatic alliance of two artists where everything was entwined: passion, hatred and artistic jealousy. Spiritual and energy exchange between the two sculptors was an outstanding phenomenon: being so close to Rodin, Camille was not only an inspiration for his work helping him find a new style and create masterpieces, she also impetuously went through the development of her own talent becoming a great master of sculpture herself. Her beauty, her youth and her genius – all this was sacrificed to her beloved man.”

Just take a look at a piece of it and marvel at its beauty.

2 Comments

Pingback:Theatre: the Architecture of Wonder – Shelidon

Posted at 15:58h, 13 December[…] It positions itself as one of the best exhibitions to be seen in Milan, alongside Van Gogh and Rodin. It’s an exhibition to be walked and re-walked, to be taken in body and soul, and its charm […]

Pingback:Picasso: the Metamorphosis of the Figure – Shelidon

Posted at 10:06h, 28 February[…] can bear a little Picasso if I could stand Rodin last season, but it might be irksome to some of us, attending an exhibition on Picasso that’s particularly […]