This one has the meat, I promise you.

But will it have oranges?

Source:

The recipe comes from a book called The good Huswifes Handmaide for the Kitchin, (you have to read this like the Swedish Chef from the Muppets). The book is dated 1594 and written by one Thomas Dawson. Who’s Mistress Duffield? We don’t fucking know.

Ingredients (4 people):

- A small skinned capon weighing around 1.5 kg chopped to 8 pieces, or the same amount of either fowl or chicken;

- a marrow bone;

- a pinch of salt;

- a cup of flour;

- a curl of butter;

- a glass of red wine;

- three oranges or half a cup of orange juice (the least sweet the better);

- a teaspoon of dried orange peel;

- a pinch of ground mace or nutmeg;

- a pinch of ground rosemary;

- a pinch of cinnamon;

- a pinch of ground ginger;

- a teaspoon of sugar;

- a cup of pitted prunes;

- a cup of currants;

- orange slices to garnish;

- verjuice, vinegar or balsamic vinegar.

The dosage is taken and adapted from this website.

Recipe:

Sprinkle the capon with salt and boil it with the marrow bone, take away the meat when it’s almost done, but refrain from eating it: you’ll need it.

Take the broth away from the fire and preferably transfer it from a metal pan to an earthenware one. Drop currants and prunes, the nutmeg, and the rosemary (though some scholars argue that it’s not rosemary but more marrow). Add a glass of wine: the original recipe mentions claret, which means Bordeaux will do just fine. Put everything back on the fire and let it simmer for a while.

Squeeze the juice out of the oranges and pour it into the simmering broth (or pour the pre-prepared juice, you lazy ass). In the land of fairytales, you’ll be able to slice these same oranges and use them for garnish, but of course, they’ll be wrecked: you’ll need to slice up more neatly a new one when the time comes.

What you’ll have to do with these oranges, however, is put them in boiling water and let them go, and repeatedly change the water until the water is not bitter anymore. Yes you have to taste it. Please wait until it’s cold enough.

When the water has taken the bitterness away from the oranges, you can throw them in the broth with everything else.

After you’ve added the oranges, put the capon back into the broth and finish cooking it. Eventually, you’ll want to remove the capon and keep the broth going until it shrinks down to stock. When it’s dense enough, add the cinnamon, ginger and a pinch of sugar, stir and use a spoonful of the mixture as a basis for the dish. Lay upon it the pieces of capon, 2 for each plate, garnish with orange slices, some rosemary leaves and a drop of verjuice or balsamic vinegar.

Original Recipe

Since the recipe is written in old English and some passages are subject to interpretation, I also give you the original one:

‘To boil a Capon with Oranges after Mistress Duffelds way. Take a capon and boil it with veal, or with a marrow bone, or whatever your fancy is. Then take a good quantity of the broth, and put it in an earthenware pot by itself. Add thereto a good handful of currants, and as many prunes, and a few whole maces, and some marie. Add to this broth a good quantity of white wine or of Claret, and so let them seethe softly together. Then take your oranges, and with a knife scrape of all the filthiness off the outside of them. Then cut them in the middle, and wring out the juice of three or four of them. Put the juice into your broth with the rest of your stuff. Then slice your oranges thinly, and have ready upon the fire a skillet of fair seething water, and put your sliced oranges into the water. When that water is bitter, have more ready, and so change them still as long as you can find the great bitterness in the water, which will be six or seven times, or more, if you find need. Then take them from the water, and let that run clean from them. Then put close oranges into your pot with your broth, and so let them stew together till your capon is ready. Then make your sops with this broth, and cast on a little cinnamon, ginger, and sugar, and upon this lay your capon, and some of your oranges upon it, and some of your marie, and toward the end of the boiling of your broth, put in a little verjuice, if you think best.’

Picture stolen from here in case you want to try one of their recipe instead.

What’s with the capon and Christmas?

Well, that’s a good question.

As Alison Weirs reminds us in her Tudor Christmas book, capon is only one of the “rich meats” traditionally served for Christmas, and its mention in this XVI Century anonymous poem is spot on:

Then comes in the second course with mickle [much] pride,

The cranes, the herons, the bitterns, by their side

To partridges and the plovers, the woodcocks, and the snipe.

Furmity for pottage, with venison fine,

And the umbles [entrails] of the doe and all that ever comes in,

Capons well baked, with the pieces of the roe,

Raisins of currants, with other spices mo[re].

Capon was also an ingredient to create and serve fantastical animals: the ‘cockatrice’ wasn’t uncommon, and it comprised of the roasted forequarters of a pig with the hindquarters of a capon itself, often adorned with other birds’ plumage, gold leaf for beak and coloured beads for eyes.

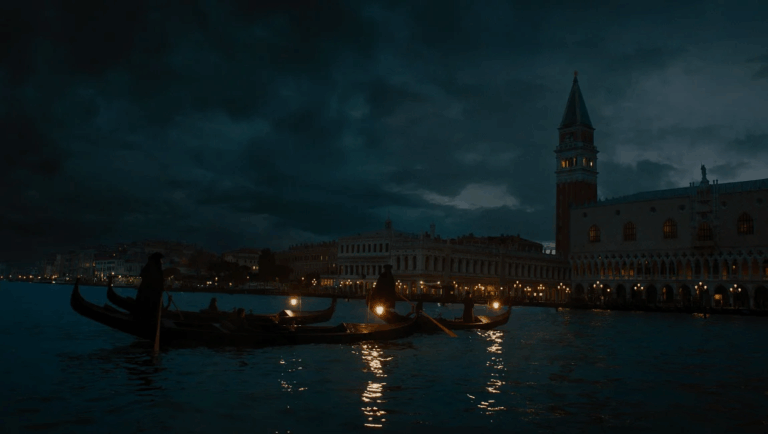

Art by Pikart.

No Comments