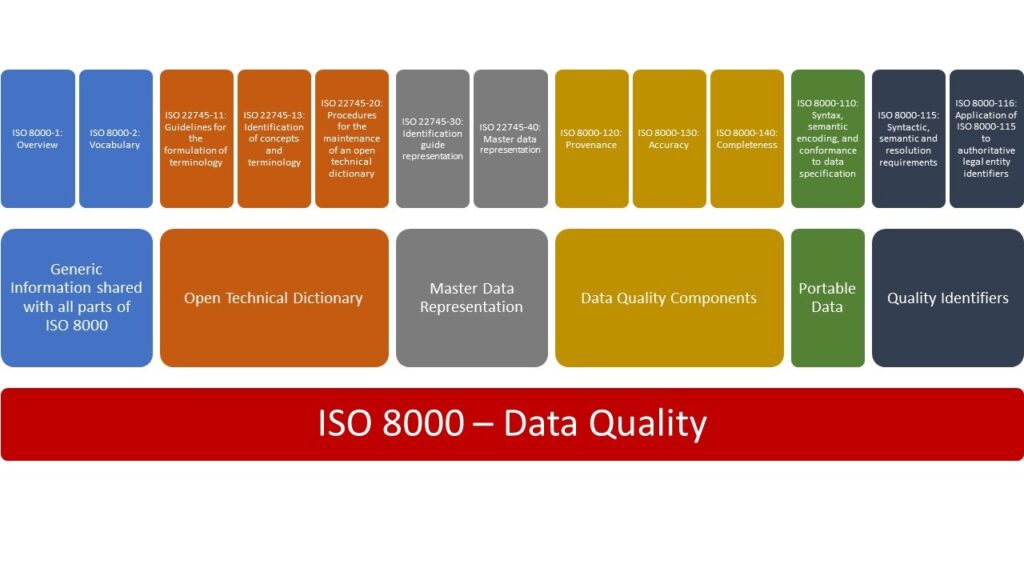

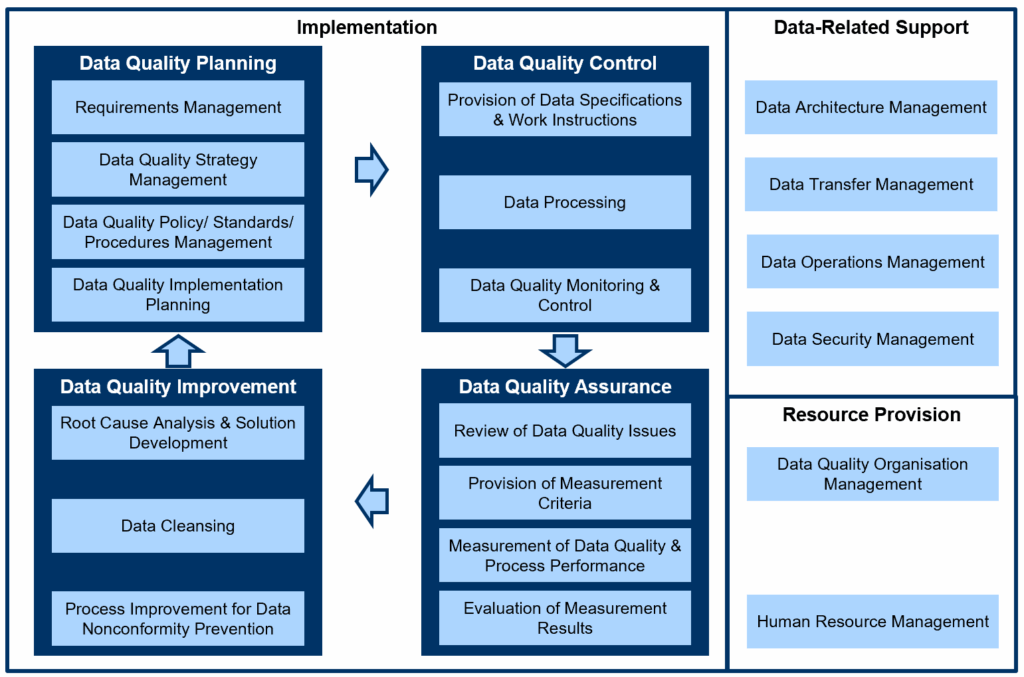

“The ISO 8000 series provides frameworks for improving data quality for specific kinds of data. The series defines which characteristics of data are relevant to data quality, specifies requirements applicable to those characteristics, and provides guidelines for improving data quality.”

1. The Architecture of Trust in the Age of Data

1.1. Data as the new concrete: how the AEC industry builds on invisible materials

The modern built environment stands on an invisible foundation. Before steel rises or concrete is poured, there exists a dense lattice of information: drawings, parameters, identifiers, coordinates, versions, and responsibilities. In the era of Building Information Modelling, data has become the new structural material: the unseen concrete binding together disciplines, tools, and intentions.

Yet unlike concrete, data is not inert. It flows, duplicates, mutates, and ages. Well, concrete ages too, that’s true. What I mean is that each exchange between design teams, consultants, and contractors reshapes data slightly, introducing microscopic cracks that may only appear long after construction is complete. What we used to call “coordination errors” are now data failures, a.k.a. misalignments between what is represented, what is known, and what is built.

In this sense, the AEC industry has never built merely with matter: trust has always been a core material as well. BIM, as it often happens, only made it more evident. And the stability of a digital building depends not only on geometry, but on the integrity and consistency of the data that defines it.

1.2. From material to immaterial infrastructures: what it means to “build” with data

The term “infrastructure” once evoked bridges and railways, but today it increasingly refers to databases, servers, and exchange protocols. These immaterial infrastructures are no less real: they sustain the same public life as their physical counterparts, and their collapse can be just as catastrophic.

To “build” with data is therefore an act of design in its own right. It involves defining relationships, dependencies, and behaviours within an ecosystem of digital objects: a door, a sensor, or a cost schedule are interconnected nodes within a living structure.

However, these systems are fragile. Unlike traditional materials, data lacks the self-evident constraints of gravity and resistance; its quality cannot be judged by touch or sight, but must be measured through conventions, schemas, and — alas! — metadata. The discipline that once relied on drawings and models must now learn to think in terms of validity, provenance, and interoperability. For materials, we have certifications and stress tests. What about data? ISO 8000 enters precisely at this threshold: it gives engineers, designers, and managers a framework for recognising data as a material subject to quality control.

1.3. Why ISO 8000 matters now: from spreadsheets to digital twins

The AEC industry’s digital journey has passed through several stages. It began with scattered spreadsheets and proprietary formats, fragile islands of information barely connected by manual coordination, and then came BIM, promising a unified model of the building only to reveal that the problem was never the model itself, but the quality of the data feeding it.

As projects evolve and people keep talking about digital twins as if they believe it, the question of trust becomes existential. Decisions about maintenance, energy performance, or safety hinge on whether the information circulating in the system is accurate, meaningful, and fit for purpose.

Within the series, ISO 8000-8: 2015 provides a rigorous vocabulary and measurement logic for this emerging reality. By distinguishing syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic dimensions of data quality, it transforms the abstract notion of “good data” into something quantifiable and auditable. In doing so, it offers the AEC sector not just a compliance tool, but a philosophical shift: from seeing data as a by-product of design to understanding it as the very medium through which design, collaboration, and trust are built. True, it’s a norm with ten years of service on its shoulders but, as it often happens, it’s still the best we’ve got.

So let’s see what it says, and how it can help us in your model analysis.

2. Understanding ISO 8000 – The Foundations of Data Quality

2.1. The ISO 8000 family: where part 8 fits

ISO 8000 is not a single standard but an ecosystem. It is conceived as a modular framework that treats data quality as a discipline with its own architecture, and it’s divided into parts addressing terminology, master data, quality management, and conformance. Within this constellation, Part 8 plays a distinctive role: it defines the concepts and methods for measuring information and data quality.

While other parts deal with processes, formats, or domains, ISO 8000-8 focuses on the analytical heart of the matter: the act of determining whether data is good enough for the purpose it serves. It provides the vocabulary and the logical scaffolding for verifying and validating data, setting the foundation for consistency across industries.

In that sense, Part 8 is not merely one chapter among many, but the keystone of the entire structure: it bridges abstract principles and operational measurement, ensuring that “quality” becomes something demonstrable rather than aspirational.

2.2. Overview of its relation to industrial and construction data

ISO 8000 emerged within the context of industrial automation and integration, responding to the need for reliable data exchange in manufacturing and supply chains. However, the challenges it addresses — heterogeneous systems, fragmented data ownership, and inconsistent semantics — are equally endemic to the construction sector.

The AEC industry shares with manufacturing a growing dependence on interoperable data models: design coordination across multiple platforms, procurement databases, facility management systems, and digital twins that span decades of asset operation. Each exchange in this network multiplies the risk of distortion.

By applying ISO 8000’s logic to construction data, we begin to treat BIM not as a single software environment but as an industrial information system, a complex ecosystem where data must move seamlessly between contexts. The same rigour that governs part numbers and product attributes in manufacturing can guide how we structure parameters, classifications, and asset identifiers in buildings and infrastructure.

2.3. From “data” to “information”: a quick taxonomy (ISO 8000-2 + ISO 8000-8)

The distinction between data and information may often seem philosophical, but ISO 8000 makes it operational. According to its definitions, data is a reinterpretable representation of information in a formalised manner, while information is knowledge about objects — facts, events, processes, or ideas — given meaning within a specific context.

In simpler terms and trying not to repeat definitions already given elsewhere: data is what we store, information is what we understand. Between the two stands metadata, the formal description that enables data to be interpreted correctly.

This triad is crucial for BIM. An information model, a spreadsheet, or a file following the IFC data scheme contains countless data points, but they only become information when structured and contextualised, when each parameter aligns with a shared understanding of what it represents. Without this interpretive layer, the model is no more intelligible than a library without a catalogue.

By codifying these distinctions, ISO 8000 lays the conceptual groundwork for evaluating not only the quantity or completeness of data, but its fitness to communicate meaning, a dimension safeguarded by the neglected suitability code and often overlooked in digital construction.

2.4. The trilogy of quality: syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic

At the core of ISO 8000-8 lies a tripartite model of data quality: syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic. These are not abstract categories but measurable dimensions that correspond to successive layers of interpretation.

- Syntactic quality concerns form: whether the data conforms to the rules defined by its metadata or schema. In BIM terms, this is the integrity of file structures, attribute names, and formats—everything that allows systems to “read” the data.

- Semantic quality concerns meaning: whether the data correctly represents the real-world entities it describes. For instance, a wall tagged as “load-bearing” must correspond to a real structural element performing that role, not simply a mislabeled object.

- Pragmatic quality concerns use: whether the data is suitable and worthwhile for a given purpose. A dataset can be syntactically perfect and semantically consistent yet still useless for a maintenance team if it lacks information on replacement cycles or suppliers.

These three dimensions together constitute what ISO 8000 calls the measurable anatomy of data quality, a structure that translates abstract trust into quantifiable verification and validation.

2.5. How ISO 8000 interacts with other relevant standards

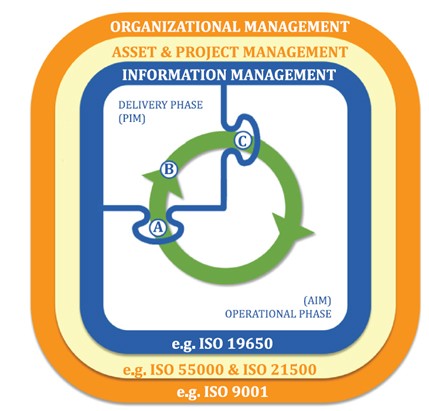

No standard exists in isolation, and ISO 8000’s power lies in how it complements existing frameworks. ISO 9000 provides the overarching philosophy of quality management — defining verification, validation, and requirement — which ISO 8000 adopts and applies to data itself. In doing so, it effectively treats information as a product, subject to the same principles of conformance, traceability, and continual improvement.

Within the AEC domain, ISO 19650 defines the organisational and procedural dimension of information management across the project lifecycle. ISO 8000 intersects this framework at the technical and semantic level: while ISO 19650 prescribes how information should be managed, ISO 8000 defines what it means for that information to be of acceptable quality.

Together, they can form a complementary pair, one governing processes, the other governing meaning. In practice, this synthesis allows the construction industry to move from compliance-driven data exchange toward a culture of verifiable, interpretable, and reusable information, aligning quality management with the very fabric of digital collaboration.

3. Syntactic Quality – When Data Speaks the Right Language

3.1. Definition and measurable rules

According to ISO 8000-8, syntactic quality is the degree to which data conforms to its specified syntax, meaning the requirements stated by its metadata.

In practice, this means that data must obey the structural rules that define how it is expressed and exchanged. Just as a sentence must follow the grammar of its language, a dataset must comply with the formal schema that governs its attributes, data types, and permissible values.

The standard prescribes that, for syntactic verification to be meaningful, several elements must be present: a complete set of syntactic rules, a formal specification of how information is structured, and explicit definitions of compliance and deviation. In other words, it is not enough to check whether data “looks right”; one must define what “right” means, describe how it will be measured, and record how deviations are reported.

ISO 8000 thus treats syntactic verification as a disciplined process rather than a heuristic exercise.

3.2. The “grammar” of data in BIM: IFC schemas, naming conventions, metadata

In the AEC industry, this grammar manifests through schemas and metadata standards. IFC, COBie, and custom property sets act as the syntactic backbone of Building Information Modelling, defining the vocabulary and sentence structure through which digital objects communicate.

An information model, even if someone recently got angry about this concept, is a structured database of entities and relationships. For the data to be machine-readable and exchangeable, every parameter — TypeName, IfcElement, Pset_WallCommon, GUID, you name it — must conform to an expected syntax. When that syntax is violated, the data loses its interoperability: software cannot parse it, scripts fail, and automation breaks down.

Naming conventions, unit consistency, and metadata completeness all fall under syntactic quality. They form the equivalent of punctuation in language: invisible when correct, disruptive when broken. A missing underscore or inconsistent case may seem trivial, but in a federated model shared among dozens of consultants, such errors propagate into compounding confusion.

Syntactic quality, therefore, is the entry point of trust. It ensures that data can move from authoring tools to validation environments, from the designer’s local folder to the shared CDE, without losing its structural coherence. Before meaning or usefulness can even be discussed, syntax must hold.

3.3. The link between conceptual clarity and operational reliability in BIM workflows

While syntax may appear as a low-level concern, its implications reach far beyond formatting. Conceptual clarity — the shared understanding of what a dataset is and how it behaves — depends on syntactic discipline.

As any computational designer knows very well, an information model riddled with inconsistencies in file naming or attribute definition becomes a fragile network: queries fail, schedules return incomplete results, and downstream systems misinterpret geometry as semantics. Conversely, a dataset that adheres strictly to defined rules supports automation, validation, and analytics with minimal friction. As it should.

Operational reliability in BIM workflows thus begins not with software capability but with linguistic consistency. By enforcing syntactic quality, teams can rely on the predictability of their data the same way engineers rely on material tolerances.

In this sense, syntax is not bureaucracy but a scaffolding, an infrastructure. It creates the conditions under which higher forms of meaning and performance can emerge, transforming isolated contributions into a coherent digital ecosystem.

This is why it’s one of the first things you should lay down when you’re writing BIM standards for a firm.

When syntax fails, systems falter in ways that are both mundane and catastrophic: files refuse to open altogether, elements vanish, schedules display a partial collection of elements, or model exchanges yield ghost elements, curtain panels start singing and dancing “Baby I was born this way”. These are not merely technical annoyances but rather signs of structural instability within the digital building.

Broken syntax behaves like a flaw in the architectural code: small, almost invisible, yet capable of undermining the logic of the entire structure. Each deviation from the formal schema multiplies uncertainty downstream, turning verification into guesswork and in collaborative projects where hundreds of contributors exchange models across different software environments, syntactic fragility quickly becomes systemic.

Unlike material defects, these cracks are intangible. They cannot be patched with concrete or reinforced with steel: they can only be prevented by precision and shared linguistic discipline. ISO 8000-8’s insistence on explicit rules, measurable compliance, and documented deviations is, therefore, not pedantry but the digital equivalent of structural inspections.

A building may stand even with a few typos in its data, but an information ecosystem cannot scale without grammatical integrity. Syntax is the first law of order in a world built of bits.

4. Semantic Quality: when Data means what it says

4.1. Definition and relation to conceptual models

If syntactic quality ensures that data is correctly written, semantic quality ensures that it means what it says. Or, rephrasing it in the words of ISO 8000-8, semantic quality is the degree to which data corresponds to what it represents. Which, if you’ll pardon me a bit of fangirling for the ISOs, it’s a beautiful way to put it. In this dimension, the standard introduces a decisive shift: from verifying formal compliance to validating correspondence between data and reality. Does this sound familiar, at least to my Italian, BIM-savvy users?

To measure semantic quality, ISO 8000 requires a conceptual model of the domain, which is the structured representation of entities, attributes, and relationships that describe how things exist and interact. This model functions as a reference ontology against which each data point is verified. It ensures that when the data says “wall,” it refers to an actual wall, and when it specifies “fire resistance,” it aligns with the correct property of that wall within the domain’s logic.

In BIM, this is not a theoretical exercise but a practical necessity. Without a shared conceptual model — explicit or implicit — teams cannot ensure that parameters mean the same thing across software, disciplines, or countries. A syntactically correct dataset can still mislead if its semantics are misaligned. A column labelled “load-bearing” but modelled as “architectural” is not an error of format: it is a failure of truth (and a clear sign its author doesn’t know how to use Revit).

4.2. Mapping entities and attributes: walls, doors, and materials as semantic actors

When it comes down to information models, entities and attributes are not static records but semantic actors, as they represent the physical and functional roles of building components. A wall, a door, or a slab is not just a geometric object; it embodies relationships: structural, spatial, regulatory, and performative. Hopefully.

Semantic quality emerges from the fidelity of these mappings. ISO 8000 defines several criteria for correspondence: entities must be mapped completely, consistently, meaningfully, unambiguously, and correctly. Applied to BIM, this means that every element in the physical or design domain must be represented once, accurately, and with coherent attributes across the entire dataset. Again, does this sound familiar?

If two walls share the same identifier, semantic ambiguity arises. If a space is modelled but lacks its function, the mapping is incomplete. If the same property “FireRating” is measured in different units or definitions across models, the representation is inconsistent. Each of these issues disrupts the building’s informational integrity and, along with it, its ability to be read, analysed, and ultimately trusted.

Semantic mapping thus becomes a form of digital modelling ethics: a commitment to ensure that what is represented corresponds faithfully to what exists or will exist. It is not merely about accuracy, but about coherence between different ways of knowing the same object.

4.3. V2 in UNI 11337-4: 2017, a.k.a. validation of content on top of the validation for presence

If this all sounds familiar to Italian readers, it’s because the Italian standard UNI 11337, particularly its distinction between validation levels V1 and V2, mirrors ISO 8000’s semantic reasoning.

V1 refers to the validation of presence, checking whether information exists within the model, akin to a syntactic check, and can easily be performed by a technician who’s skilled in information modelling but isn’t qualified or particularly competent in the discipline they’re checking. It’s a very popular level in validation, as you can create a company with this scope, hire BIM monkeys, underpay them, and cash in on public procurement without any particular responsibility and without offering anything a script couldn’t check.

V2 advances to the validation of content: verifying that the information present is correct, meaningful, and consistent with the intended purpose. As you can imagine, it’s a lot less popular.

This second layer of validation corresponds to the semantic quality defined in ISO 8000-8. It recognizes that completeness without correctness is a false assurance. A model can be filled with data yet remain unreliable if that data misrepresents reality.

In practice, achieving V2 validation requires establishing reference dictionaries, classification systems, and model-checking rules that reflect the conceptual structure of the project. The aim is not just to confirm that a property is populated, but that it conveys the right meaning according to the shared domain model.

Thus, the convergence between ISO 8000 and UNI 11337 points toward a broader methodological principle: quality management in digital construction must evolve from counting data to interpreting it. Only then can information management become knowledge management.

4.4. Ontologies and digital confusion: why meaning breaks across software

Even with clear definitions, semantic drift is a persistent risk in BIM environments: as data travels across software, formats, and disciplines, its meaning often fractures. Entities are reinterpreted, property sets are renamed, and local conventions overwrite standardised ones.

Part of this fragility stems from the lack of shared ontologies, intended as formalised conceptual models that define what each term means and how it relates to others. Efforts such as the buildingSMART Data Dictionary (bSDD) and ISO 12006-3 aim to fill this gap, yet in practice, they coexist with countless taxonomies and project-specific templates.

The problem intensifies with the introduction of Levels of Information Need, which tie information requirements to specific purposes within the project lifecycle. Without semantic alignment, these requirements are easily misinterpreted, at least in my experience. What is “as-built” data for a contractor may not be “as-maintained” data for a facility manager. The syntax remains valid, but the meaning shifts subtly, invisibly, and dangerously.

This is where ISO 8000’s semantic rigor becomes indispensable: it reminds us that meaning is not embedded in the file, but rather arises from the agreement between systems, people, and contexts. The more digital our infrastructures become, the more they rely on this fragile consensus.

5. Pragmatic Quality: when Data works in the Real World

5.1. Definition and scope of pragmatic validation

According to ISO 8000-8, pragmatic quality is defined as conformance to usage-based requirements. While syntactic and semantic quality deal with correctness in structure and meaning, pragmatic quality concerns relevance: whether the data is suitable for the task at hand, within the specific context of its use. And this is where some portions of the Levels of Information Need framework might come back into play.

This distinction introduces a human dimension to data quality. It acknowledges that information is not inherently good or bad> it is good or bad for something. A perfectly formatted and semantically accurate dataset may still be pragmatically poor if it fails to meet the needs of the people or systems that depend on it.

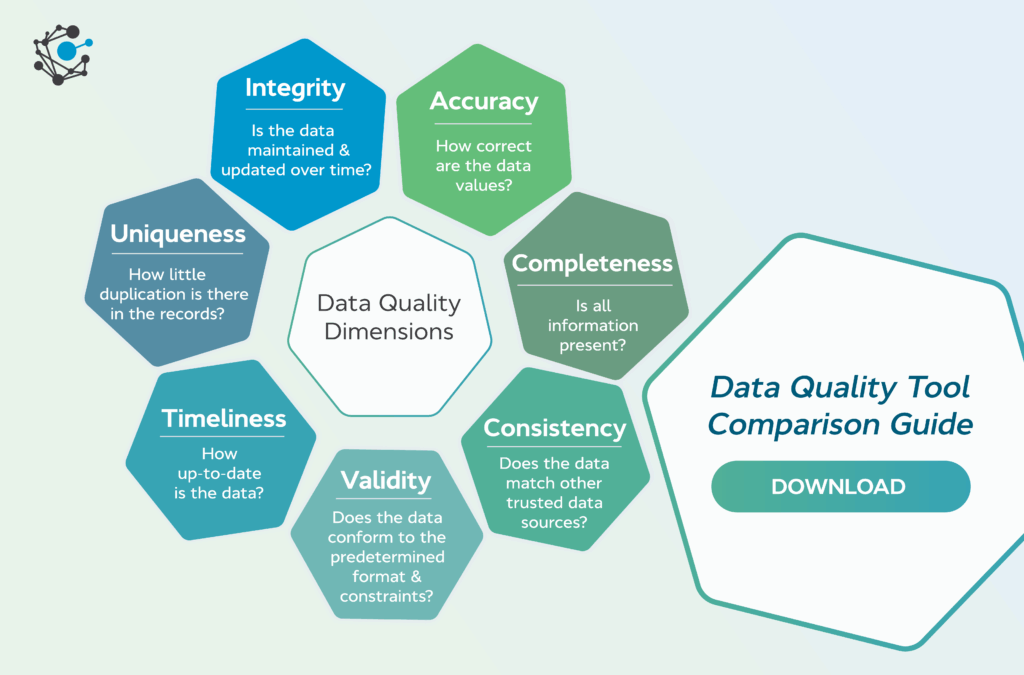

ISO 8000 formalises this idea by requiring explicit definitions of quality dimensions such as timeliness, completeness, accessibility, accuracy, and credibility, together with metrics and methods of validation. These are not universal: each organisation, project, or use case must define them according to its business needs.

In construction terms, pragmatic quality is the test of usefulness. It is the moment when the abstract correctness of data is confronted with the lived complexity of design, construction, and operation.

5.2. Context and purpose: the same model, many meanings

If you followed me so far, BIM makes visible a paradox that ISO 8000 anticipated: the same data can be of high quality for one purpose and poor quality for another. As we well know and as we’ve been trying to say when we connected LODs with model uses, a model created for visualisation may have sufficient geometric and parametric accuracy for design review, but lack the information required for procurement or asset management. Conversely, an operations-oriented dataset might contain detailed maintenance schedules but no usable geometry. In both cases, the data is syntactically valid and semantically consistent but pragmatically misaligned.

This relativity underscores why pragmatic validation must always specify the intended use and viewpoint. ISO 8000-8 explicitly notes that different user groups can utilise the same data for different purposes, and that these purposes must be declared to evaluate quality correctly.

In practice, this means defining model uses at the outset of a BIM execution plan, linking them to clear information requirements, and verifying not only the presence or correctness of data but its fitness for the chosen workflow. Pragmatic quality thus becomes a measure of empathy: how well data anticipates the needs of its future interpreters. Reassuringly enough, this is nothing new. Or, at least, it shouldn’t be.

5.3. Measuring pragmatic quality in information management

The measurement of pragmatic quality requires translation from abstract principles into operational metrics. In a construction context, these might include:

- Timeliness.

Is the data delivered when it is needed in the project sequence? - Accessibility.

Can all stakeholders retrieve and understand the data without technical barriers? - Completeness.

Does the dataset cover all entities and attributes relevant to its intended use? - Consistency over time.

Does the data remain valid as the project evolves, or does it degrade through uncontrolled revisions?

Validation methods can range from automated model checks to structured interviews or questionnaires with end users — a point ISO 8000 makes explicit — but defining better validation methods isn’t the point of this discourse. The inclusion of qualitative evaluation is significant: it recognises that pragmatic fitness cannot be fully automated. Even the most rigorous validation scripts cannot predict every situational dependency of data use.

In this sense, pragmatic quality occupies a middle ground between engineering and interpretation. It treats the model not as an immutable artefact but as a communicative instrument whose success depends on how it performs in the hands of its users.

5.4. The pragmatic frontier: from compliance to consequence

Let’s push the point a little further down the hill.

In the AEC industry, the absence of pragmatic quality control often surfaces only at the moment of failure: when all those as-built models we’ve been delivering will prove useless for facility management, or when the digital twin of a bridge won’t be able to integrate its monitoring sensors because there aren’t any sensors to be integfrated. These won’t be software errors but mismatches of expectation and context.

The promise of digital transformation, when pursued consciously, lies in closing that gap: pragmatic validation redefines data quality not as a bureaucratic end in itself but as a condition for continuity of meaning across the asset lifecycle. It forces each actor to articulate what information they truly need and to design data structures accordingly, which is the foundational basis for the Levels of Information Need as defined by ISO 7817-1: 2024 (the relatively new version of the original EN 17412-1: 2020).

When a model ceases to be an abstract repository and becomes a reliable partner in decision-making, pragmatic quality has been achieved. The measure of success is not compliance, but usefulness. A form of operational grace, if you’ll forgive my poetic license, that bridges the technical and the human.

6. Measuring and Managing Quality

6.1. The architecture of measurement in ISO 8000-8

At its core, ISO 8000-8 is not a conceptual standard but a measurement framework, as it defines how organisations can transform the abstract notion of data quality into an auditable process.

Measurement, in this context, means establishing a set of criteria, scales, and confidence levels through which the quality of data can be expressed quantitatively or qualitatively, and these criteria can’t possibly be imposed universally: they must be tailored to each domain’s expectations and requirements. ISO 8000-8 deliberately refrains from setting thresholds, but only requires that they be explicitly defined and justified.

This emphasis on transparency is crucial: it recognises that what counts as “good enough” depends on context. A hospital, a railway, or a residential project may have entirely different tolerances for missing, delayed, or inconsistent data. Quality is not an absolute but a negotiated equilibrium. A concept many tyrannical BIM managers and coordinators might struggle to understand.

The act of measurement, therefore, becomes a form of project governance: organisations are forced to clarify their expectations and make explicit the assumptions under which their data is considered trustworthy.

6.2. Verification and validation: two lenses of trust

ISO 8000 borrows two central concepts from ISO 9000 — verification and validation — and redefines them within the domain of information.

- Verification is the confirmation, through objective evidence, that specified requirements have been fulfilled; it deals with checking whether the data conforms to formal expectations.

- Validation is the confirmation, through objective evidence, that the data is fit for a specific intended use; it concerns the adequacy of information in practice.

It’s a different definition than the one given by technical norms in Italy, and very different from the operational praxis, hence it might generate some confusion. Think about it this way:

- Verification answers the question: is this data correct according to the rules?

- Validation answers the question: is this data useful for its purpose?

In information management, verification typically manifests as automated rule checks ensuring that parameters exist, values follow naming standards, or geometries comply with model coordination requirements. Validation, by contrast, would involve assessing whether the information actually supports decision-making: whether a property aligns with design intent, regulatory compliance, or asset management needs. Not many projects would pass it.

Together, verification and validation establish a dual lens of trust — one formal, one functional — through which data quality can be both proven and experienced.

6.3. Establishing thresholds and scales

One of ISO 8000-8’s most important contributions is its insistence that any claim about data quality must include a declared scale and a statement of confidence. A verification process without thresholds is meaningless; it tells us only that checks were performed, not whether the results are acceptable.

In practical terms, this means defining measurable targets such as:

- How recent or complete must the dataset be to be considered pragmatically valid?

- What proportion of attributes must be populated for the model to pass syntactic verification?

- How much deviation from reference values is tolerable before semantic quality fails?

These questions shift quality management from intuition to evidence-based decision-making. Moreover, they create the conditions for continuous improvement: once metrics are defined, organisations can track progress, compare projects, and refine their standards over time.

Within BIM, such metrics are crucial and could be integrated into dashboards or automated model audits, creating a traceable record of both verification and validation events as a form of digital accountability. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

6.4. Reporting and traceability

ISO 8000-8 closes its methodological loop with a requirement for structured reports called conformance statements, which record the subject dataset, the criteria used, the results obtained, and the identity of those performing the assessment.

This emphasis on documentation is meant to ensure that data quality is traceable. Every model revision, every dataset exchange, and every validation report contributes to a verifiable history of the information’s reliability.

In the construction context, such traceability has profound implications, as it would enable designers and contractors to demonstrate compliance not only with standards but with contractual and regulatory obligations. More importantly, it would transform the model into a living record of decision-making and into a mirror of how knowledge evolved through the project.

In a sector where disputes often hinge on interpretation, traceable validation would provide something rare: evidence.

6.5. From measurement to management

Once measurement becomes systematic, it can evolve into management. ISO 8000-8 does not end with the act of assessing data quality but points toward its continuous improvement and, as such, it perfectly aligns with that ISO 9001 framework for quality that’s the explicit reason for doing BIM in the first place, at least according to ISO 19650.

Data quality management means embedding verification and validation into the lifecycle of digital assets — design, construction, operation, and decommissioning — so that information maintains its integrity across time and organisational boundaries.

When integrated with ISO 9001’s quality management systems and ISO 19650’s information management processes, ISO 8000 transforms data governance into an ecosystem of living quality: a continuous calibration between rule, meaning, and use.

Ultimately, verification and validation the way ISO 8000 intends them should become complementary habits: one ensures that the data speaks correctly; the other that it says something worth hearing. In their interplay lies the possibility of a genuinely reliable digital built environment, an infrastructure of trust.

Conclusion: Data Literacy in Construction

The idea of data quality often enters the conversation as either a matter of control or a technical necessity to ensure consistency, compliance, and automation. Yet what ISO 8000-8 ultimately teaches is that quality is not control, but understanding. Behind every verification rule and validation report, a deeper question should lie: do we, as an industry, comprehend the language we are speaking through our data?

Digital construction aims at reaching a point where the management of information would no longer be an auxiliary process but the primary medium through which buildings are conceived, constructed, and maintained. In this landscape, data literacy involves not only knowing how to produce data that passes a check, but also how to interpret, contextualise, and question it. And the responsibility of BIM professionals would extend beyond compliance, just as it did for architects and engineers in their own domain.

To think of data as a shared language rather than as a control mechanism changes everything. Language, after all, is a medium of negotiation, not domination, am I right? Regardless of what some people think, it thrives on mutual understanding and continuous adaptation. In a federated BIM process, this means accepting that no single actor owns the truth of the model and that data quality is co-created through interpretation, feedback, and transparency.

This shift from control to conversation reframes digital practice as a collaborative act of translation. Each dataset is a message; each exchange, a dialogue.

Cultivating this interpretive literacy is what turns standards into living culture. ISO 8000-8 offers a grammar for trust, a structure within which meaning can circulate reliably between humans and machines. Its true value lies not in prescribing how to check data, but in teaching how to think about data: to see it as a material shaped by context, intention, and care. In this sense, data quality becomes a form of design ethics: just as the architect is accountable for the safety and legibility of built form, the digital designer bears responsibility for the clarity and reliability of the information that defines it. To ensure that a model speaks truthfully is to respect the labour, intelligence, and decisions that depend upon it.

The construction industry’s digital future will not be built solely on better tools or smarter standards, but on this culture of literacy where data is no longer a by-product of design, but its very language.

Quality, in the end, is not the absence of error but the presence of meaning. And meaning, as ISO 8000 quietly reminds us, is the most enduring structure we can build.

No Comments