We’re taking the run-up to prepare for April 15th, when Impressionism will celebrate 150 years from its conventional birth. It was April 15th 1874 in fact, at the studio of photographer Félix Nadar in 35 Boulevard des Capucines, Paris, when the group of rascals later known as the Impressionists held their first structured exhibition. It will last for a month, until May 15th. It featured the works of around 30 independent artists, the core group including Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, Frédéric Bazille, Berthe Morisot, Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro. They presented a total of 175 works. “Impression, Soleil Levant” was one of the paintings, by Monet, and gave the movement its name.

The exhibition was met with mostly negative reviews from critics, who found the works unfinished, sketchy, and lacking in conventional techniques, which was kind of the point.

Palazzo Reale in Milan marks the occasion by exhibiting fifty-two works by Renoir and Cézanne from the collections of the Musée d’Orsay and the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris, retrace their life and artistic development through their most iconic paintings, from portraits to landscapes, still lifes and scenes of high life during the belle-epoque. The exhibition is completed by a comparison between two works by Cézanne and Renoir and two paintings by Pablo Picasso.

I went to see the exhibition yesterday (on a Friday afternoon) and it was overcrowded with elderly people, which generally is a good thing. Unfortunately, impressionism always attracts a certain kind of people, for some reason, and the exhibition quickly turned into a match: who was better between Cézanne and Renoir? Was Cézanne really able to paint? Who would win in a fight? Not the soothing, calming experience I was expecting from seeing an exhibition in the middle of the afternoon between one meeting and the other, I’ll admit.

As such, you’ll forgive me if my judgment of the exhibition has been a little biased by the experience.

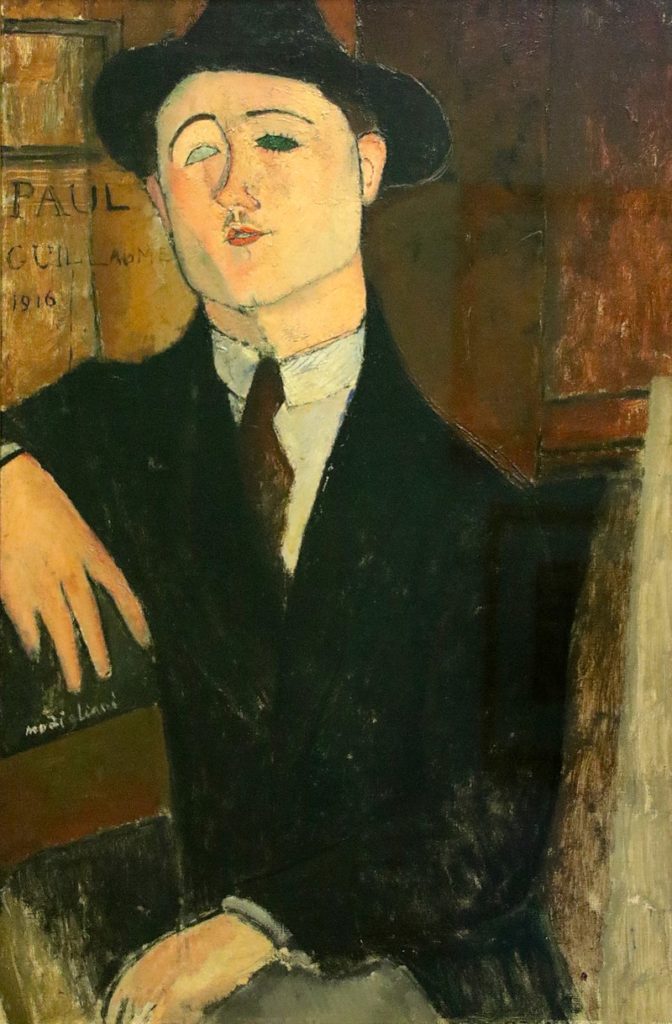

Paul Guillaume

The show opens with a portrait of Paul Guillaume and a room dedicated to him as a collector.

Born in Paris in 1891, Guillaume did not come from a wealthy or cultured background: he ventured into the art world as a merchant, before business went well and he could become a collector himself, and was introduced into the salons by Guillaume Apollinaire, the famed, Polish-born French poet and playwright. Guillaume soon opened his own gallery in Paris and became a key figure in supporting and exhibiting the works of avant-garde artists, and he played a crucial role in the careers of several prominent artists, including Amedeo Modigliani, whose portraits of Guillaume himself are well-known today. The portrait as at the Museo del Novecent, right across the square, but I guess Palazzo Reale and this museum hate each other, ’cause there’s not even a mention of this masterpiece in the room dedicated to Paul Guillaume.

Guillaume also championed the works of Chaïm Soutine and Constantin Brâncuși, providing them with a platform and financial support, and was one of the first Parisian art dealers to organize exhibitions of African art.

His presence at the beginning of this exhibition is due to the prominence of Renoir and Cézanne’s works in his massive collection, known as the Jean Walter and Paul Guillaume Collection, and amassed with the aid of his wife (later his widow) Domenica Walter. Whenever I will say that a divided painting has been reunited or restored, they did it.

The collection is currently housed at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris, where many works come from.

Here’s the portrait exhibited in the show, painted by the Dutch artist and friend Kees Van Dongen.

After the Tunnel: two families compared

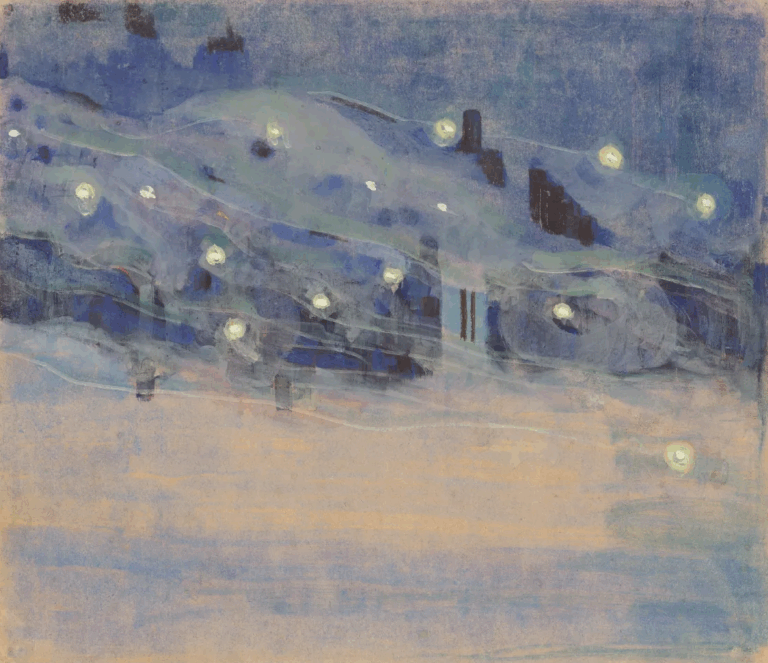

After a charming tunnel made of stained glass, mosquito nets, wooden panels and windows meant to immerse you in the Provencal, open-air atmospheres of the works by both painters, a small room shows us the two timelines for the artists’ lives, and a couple of paintings of their families.

Cézanne married Marie-Hortense Fiquet in 1886, after they had been together for about fifteen years. The relationship was hidden from the artist’s family because she was a worker in his father’s factories and a part-time model, they had met at a Paris art school, and Cézanne was rightfully concerned that his wealthy father would object to their liaison, and the secret was kept even after the birth of their son Paul.

The paintings of her, however, aren’t the ones you expect from an artist representing her muse. She was the mother of his child, and he paints her soberly, except possibly the one where she’s nursing their child, which prompted some critics to say that his desire for his wife soon had dwindled, and indeed we have some accounts of Cézanne himself stating the same. I guess it would be excusable for a relationship to change after a couple has a son, but apparently this is not the case for artists nor for art critics. What do I know.

Over here you can find an extensive collection of portraits and paintings of Hortense.

Not included in the show, I believe this is one of the most touching paintings done by Cézanne: Hortense is nursing their son Paul.

A 2014 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art explored the subject a little more deeply, diving into letters and accounts.

Far from idealized as a woman or a beloved mate, she usually appears stiffly reserved, a dignified enigma. […] His letters to friends suggest that he regarded her as a shallow and irritating person. He excluded her from his will, leaving everything to their son. Yet he painted her repeatedly over more than 20 years. Go figure.

Cézanne’s story has some similarities with Renoir’s.

Aline Victorine Charigot was a dressmaker, also a part-time model, and she had met Renoir in 1879 when she started posing for him. She was twenty, and he was nearly forty. Regardless of this, daddy’s son kept the relationship a secret for fear of disapproval even when the couple had a son, Pierre, in 1885. They eventually married in 1890, but I must say that the similarities stop here: they had two more sons, Jean (born in 1894) and Claude (born in 1901), and Aline remained a constant source of support and inspiration for Renoir throughout their marriage. She not only modelled for him but also managed his household and cared for him as his health declined in later years. Renoir’s depictions of his family and wife are of a happy, radiant nature.

The line-up

After this introduction, we reach the first room, with a line-up of works by Cézanne facing a similar line-up of paintings by Renoir.

The contrast is stark: Cézanne chases geometrical rigour, and will later say that you can paint anything if you master the representation of three primitive forms, while Renoir is researching atmospherical effects with a delicacy of both strokes and palette. The room, however, is meant to highlight their similarities in the choice of subjects, next to the difference in their style: still lives, landscapes, portraits, people bathing, and the inclusion of other people’s works in their paintings will be themes we’ll find throughout the entire exhibition.

It’s hard to pick a favourite, but here’s some of the paintings that had the strongest impression on me.

Renoir in Algeria

Renoir first visited Algeria in February 1881, returned for a second stay the following year and lingered in those areas until his health allowed him. North Africa suggested him new colours for his open-air paintings, a new kind of light, and his tendency towards the “portrait of trees”, a genre inaugurated by Camille Corot and very dear to the impressionists, was enriched with ned Mediterranean plants such as the agave and the prickly pear. This spot is on the outskirts of Algiers and there are no wild women here: the name only references a nearby café. It’s one of the first examples in which Renoir uses shades of deep blue for the shadows, in contrast with the bright colours.

“Painting is, above all, manual work.”

– PIerre-Auguste Renoir

A Three-part masterpiece (reunited)

It’s impossible not to fall in love with this work and its troubled history.

Paul Cézanne paints this Boat and the Bathers as a unique piece, in a very unusual format, and of course people cut it up to sell it better. It could have been an overdoor decoration for the an apartment in Paris, the residence of the collector Victor Chocquet, friend to both Cézanne and Renol, and it was restored after its purchase by the Musées Nationaux.

It’s similar to another couple of studies by Cézanne, in which a group of female bathers is studied next to a group of males.

Though there is no indication that these were part of a unique work as well, it’s obvious that Cézanne is interested in the duality of how men and women experience the same playful activity, bathing outdoors, and it’s refreshing to see how both groups are free of any sexualization, and treated almost as if they were equal in their enjoyment of the fresh air.

He would start painting these subjects around 1875 and never abandon them.

Indoor moments

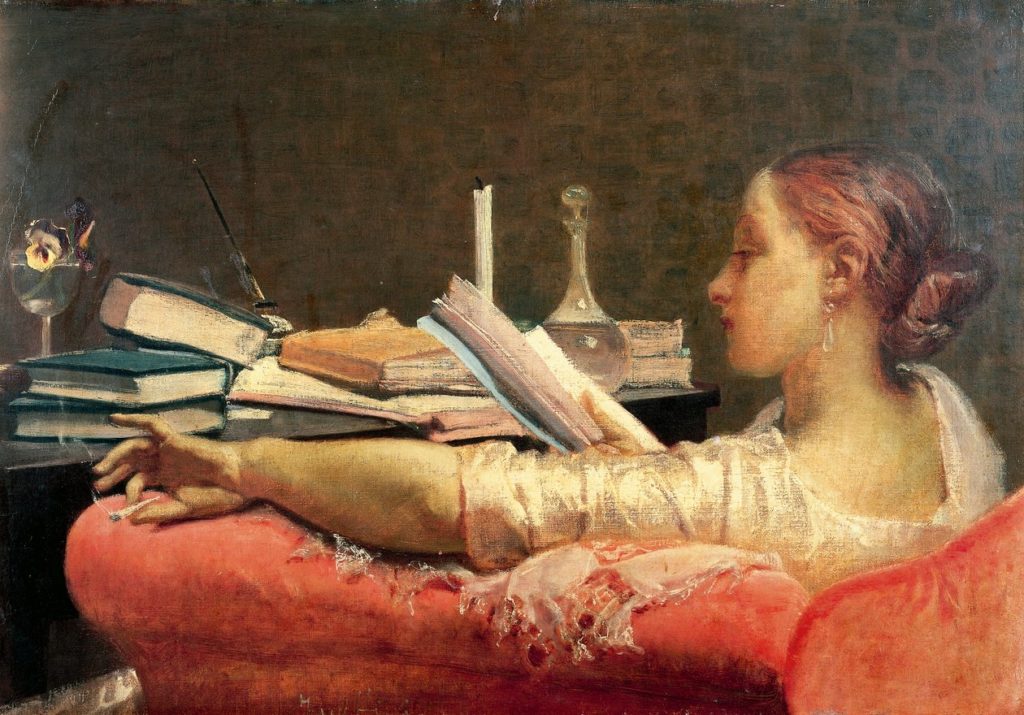

If the outdoors is room for playful sports and for observing nature, both painters don’t shun away from painting indoors, where they choose to depict intimate moments. Two girls whispering each other secrets, two women playing the piano.

Yvonne and Christine Lerolle playing the piano

Painted in 1897, this work represents the eldest daughters of the French painter and collector Henry Lerolle, a friend of the Renoir family, and it was eventually purchased by Henri Roujon during an exhibition dedicated to the painter. Prompted by Stéphane Mallarmé, Roujon intended to establish a collection of living artists at the Palais du Luxembourg in Paris, and it’s significant how the choice fell on such a domestic scene. Time indeed had changed.

Like a previous Jeunes filles au piano (above), this painting treats the subject with freshness and impressionistic chromatic harmonies, abandoning the severe style of the previous decade. The theme reeks of bourgeoise optimism and appeals to the collectors of that social class: young girls are immersed in a domestic atmosphere, intent on games, reading or – as in this case – musical exercises. We have stupendous examples of the same spirit from painters of the same era here in Northern Italy.

Renoir is however more influenced by his contemporaries in Paris, such as the incredible Berthe Morisot.

Renoir describes various details of the domestic environment, dwelling on the details of the golden chair and on the two paintings hanging on the wall: they have been identified as Jockeys at the Start of the Race and Group of Ballerinas, both by Degas, which must have been present in the house of Henry Lerolle.

Portrait of two girls

The two girls depicted here appear in several of these works, including the version of the Girls at the Piano from the Walter-Guillaume collection and the very same one purchased by Henri Roujon for the Palais du Luxembourg. Their identification isn’t certain, as they’re protected by not being named in the title.

Gabrielle and Jean

With more certainty with can identify the subject of this other painting by Renoir.

Gabrielle was a cousin of the painter’s wife Aline, and was often employed by the couple in the care and custody of their son: she was indeed one of the painter’s favourite models and appeared in a substantial number of paintings, such as Gabrielle, Jean and a Little Girl (1895), The Artist’s Family (1896), The Child’s Breakfast (1904) and The Writing Lesson (1906).

Renoir’s The Child’s Breakfast is an incredible work when it comes to… well, pretty much everything, from the composition to the treatment of the light, to the stark contrast between the man who’s missing on the playful, domestic scene in the background, and the nanny. We can almost guess how Jean, dressed in black like his father, is almost in-between.

Born in 1894, Jean is the painter’s first son with Aline. In his early years he’s portrayed with touches that remind us of Reinassance paintings of angels, with blonde hair that’s often long and attired in what we might describe as a feminine fashion. Here he still has short, curly hair, and the couple is playing with a cow and a female figure, possibly a shepherdess, but they’re blending into the table and bathed in the light: can admire the flowers on the wallpaper, but we’re not privy to the tales the two are telling each other.

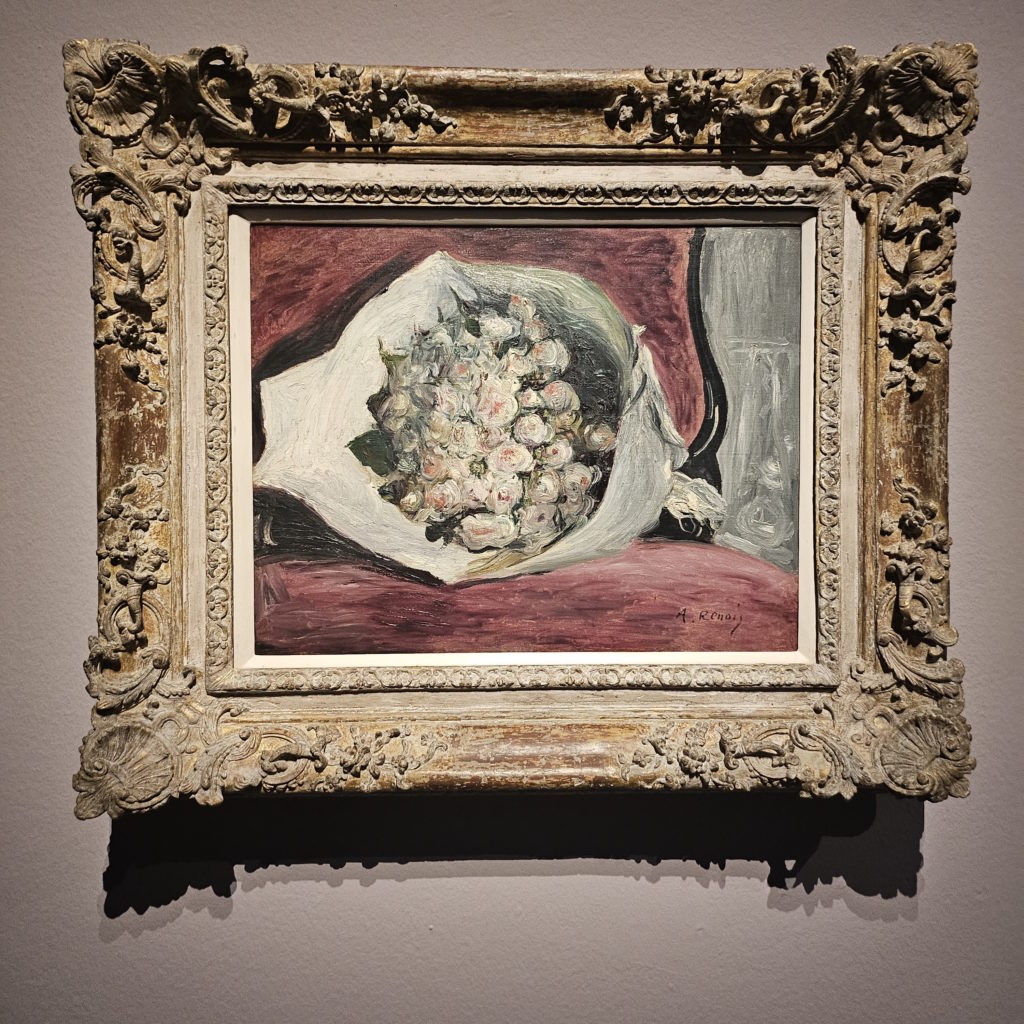

Still lives

Renoir wasn’t primarily known for still lifes, especially compared to his prolificacy in portraying figures and landscapes, but he did occasionally incorporate them into his artistic repertoire and they’re astonishing. Some art historians suggest that Renoir’s interest in still lifes increased later in his career, particularly after the onset of rheumatoid arthritis in his hands and fingers, but that’s not how we like to think about it: drawing inspiration from the French tradition of flower painting and 17th-century Dutch floral still lives, he incorporated his signature Impressionist style, characterized by loose brushstrokes, vibrant colours, and an emphasis on light and shadow play.

He can’t possibly have known them, but please compare that still life with the work of some Renaissance painters like Fede Galizia (I wrote about her here) and Giovanna Garzoni (here).

Renoir’s still lifes can be grouped into two categories: the domestic ones, often featured flowers in vibrant bouquets displayed in vases, and fruits; and the social ones, where the flowers and fruits are telling us a story of parties, and of the people they were intended for. In the last category we find this amazing bouquet, abandoned on the armchair of a salon or the opera. Who was it for? Why did she leave it there? We’ll never know.

On the other hand, Cézanne’s attention to still lives is much more than marginal, and he actively explored the genre throughout his career. Though Cézanne’s early still lifes were influenced by the work of Gustave Courbet, his depiction of fruits and everyday objects in a dark and sombre palette soon became the foundation for his later explorations of form, colour, and composition.

As Cézanne matured as an artist, his still lifes became more than just realistic depictions of objects: he began to experiment with perspective, breaking away from the traditional one-point and manipulating viewpoints to create a sense of depth and dynamism in a way that was capital for what we will call cubism. His vibrant hues and contrasting elements explored the relationships between forms, more than the relationship between everyday objects and light. A defining characteristic of Cézanne’s still lives is his emphasis on form and structure. He simplified complex shapes like fruits and vessels, reducing them to their basic geometric components – spheres, cones, and cylinders.

An Atelier Recreated

The transition between the central section of the exhibition and the last rooms is marked by the recreation of environments that could remind us of the painters’ ateliers, in both daylight (simulated, of course) and artificial light.

It’s charming enough. Though it’s a challenge for people to understand that they can’t go inside and touch stuff.

Subjects Compared

The last room includes three pairs of paintings with the same subject, one by Renoir and one by Cézanne:

- bathers;

- still lives;

- landscapes.

They’re all highly representative of the differences and similarities between the two friends, but the most impactful possibly is the section with the two bathers: a classical one by Renoir, influenced by Boucher’s Diana Resting after her Bath, and Cézanne’s groundbreaking composition that Picasso will love. Of course I prefer the first one.

Picasso because of reasons

The last room features a still life and a naked woman by Picasso, compared to a still life by Cézanne (we’ve seen why) and a naked woman by Renoir because, I guess, we liked it.

No Comments