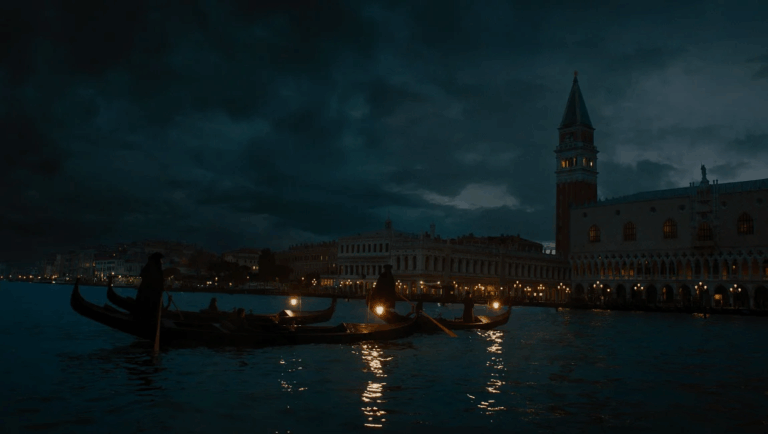

Bruges is a truly enchanting city, especially if you have a soft spot for waterways, and it’s truly difficult to select only four things to see (but I had to: they were two in Ghent, three in Antwerp… it’s all about the progression).

There are a couple of spots everyone visits and I won’t be mentioning them because they’re fairly obvious: the Rosary Quay (Rozenhoedkaai), Ezelpoort, the Conzett Bridge… basically if you follow the waterways, you’ll find charming spots at every corner.

I’ll try and point out a couple of other places instead.

1. The Basilica of the Holy Blood

Ignore the upstairs church, where a serious priest sits all day in front of a piece of cloth and loudspeakers are boasting worship of the titular holy blood, brought back to Europe while we were ravaging the Middle East. Stay downstairs instead, and turn left, push through the door and enjoy the silence.

The building consists of two chapels one on top of the other, and the lower one, the chapel of Saint Basil, is one of the best-preserved Romanesque churches in the West Flanders. It was built between 1134 and 1149, and it’s dedicated to Basil of Caesarea because of another relic that was brought back by Count Robert II from Cappadocia (modern Turkey). It is scarcely decorated, aside from a stunning XII representation of the baptism of Saint Basil you’re likely to miss if you don’t enter the annexed chapel to the right and turn around: it’s on the tympanum above the connecting door.

If you want to go upstairs, you’ll do so through a stunning staircase with double heights, a marble-lined brick ceiling and beautiful stained glass windows overlooking the Burg square. I have no idea why the windows bear the Tudor rose.

The entrance of the Basilica is also worth a mention, as it’s not your traditional church: all it offers to the square is a slice of a Gothic facade, and those windows you see are the ones giving light to the staircase. The golden statues represent angels on the upper level, and historical figures on the lower one.

2. The Church of Our Lady

They will tell you that you have to go there because there’s a statue by Michelangelo and I’m not saying I disagree. It’s cute. I’m just saying there’s so much more to see than that.

2.1. The Painted Graves

According to what’s written on the plaques, around 1270 it became customary to paint the inside of brick-lined graves. It’s unclear who started the tradition, but if you have to spend all eternity locked inside a box I agree you’re going to need something to read.

The Virgin and the Child are usually depicted at the door end, to intercede with God on behalf of the deceased, while the crucified Christ is often depicted at the head end. The sides are decorated with angels, often with incense burners to fend off the smell of decay, who had the task of accompanying the dead to Heaven.

The plaque describes these works as “rudimentary”. We have two very different ideas of what the word means.

What’s astonishing is that the artist had very little time to paint these pictures, as the deceased were often buried on the same day they died: they painted freehand on the wet, quick-drying lime and this results in pictures of astonishing vividness. By the XV century, paintings were replaced with drawings on paper.

2.2. The tomb of Charles the Bold and Mary of Burgundy

They won’t tell you much about the people behind these two stunning golden sepulchres placed at the centre of the apse, but boy, oh boy, there is stuff to tell.

Charles the Bold was Duke of Burgundy from 1467 to 1477, when he died in the battle of Nancy and his body was allegedly found stripped, half-chewed by wolves and half-embedded in frost, up to the point that they had to go and fetch specific instruments to carve him out of the ice.

Mary of Burgundy was the daughter of Charles from his second marriage to Isabella of Bourbon, and married Maximilian of Austria right shortly after her father’s death in battle, to fend off the French king Louis XI who wanted her lands. Right before her marriage, in fact, she had been forced to sign a charter of rights known as the Great Privilege, in the nearby city of Ghent, which reinstated to the provinces several privileges her father had revoked. Amongst these, she was not allowed to marry, to declare war or levy taxes without consent of the States, but her marriage to Maximilian had already been officiated, if not officialised. She and her husband slowly weakened the treaty, until it was abolished in 1482. She wouldn’t be alive to see this, though: she had befallen an accident during a falcon hunt in the woods near Wijnendale Castle, where her horse had fallen upon her, breaking her back.

Their court is said to be the origin of the legend of Dr Faust, as the priest, abbot and humanist Johannes Trithemius was accused of necromancy and, according to Luther, had summoned the spirits of past leaders to entertain the couple.

3. The City Hall

Built in a late-Gothic style between 1376 and 1421, the hall stands in Burg Square and it’s one of the oldest city halls in the region. That’s why a local architect called Louis Delacenserie and a neo-Gothic architect named Jean-Baptiste Bethune thought it best to restore the interiors and, between 1895 and 1905, they created a fake timber structure and decorated the walls with colourful scenes of the city’s history.

This is not why I’m recommending you to go.

Media error: Format(s) not supported or source(s) not found

Download File: http://www.shelidon.it/splinder/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/20231204_150921.mp4?_=1The thing you need to see is in the annexe room, and it’s a large augmented reality map telling you the territory’s history. If you wish to understand the long and complex relationship between the region and water, from Roman to modern times, you can’t miss this installation where a soothing voice (at least in English) will guide you through the many changes and evolutions, floods and human interventions, of this fascinating land.

A mention of merit to the one who thought to have earphones in different colours based on the spoken language, as it somehow creates an unspoken connection between visitors and it mitigates the sense of isolation and alienation these shows might unwillingly inspire.

4. The “Ten Wijngaerde” Beguinage

The structure is one of the few preserved beguinages in the area, which means a settlement where lay, independent women lived a self-sufficient life of sharing and communing around the values of early Christianity (more on that later).

The beguinage was founded around 1244 by Margaret of Constantinople and was recognised as an independent parish in 1254. Its complete name, “Princely Beguinage Ten Wijngaerde”, refers to 1299 when it came under the direct authority of King Philip the Fair.

The complex includes a Gothic church and around thirty white-painted houses of later construction, dating between the XVII and the XVIII century, built around a central yard. Access is through the three-arched stone bridge, the Wijngaard Bridge, where you can see an effigy of Elizabeth of Hungary, the matron of many beguinages. The gate itself is from 1776.

The canal ends up in the Minnewater, the Lake of Love, where tons and tons of swans swim around.

Do not be fooled by these beasts’ appearance: they have a legendarily bad attitude, and I mean it literally.

4.1. The Curse of the Swan

As you’ll read at the Lanchlas Chapel in the abovementioned Church of Our Lady, swans in Bruges are connected with the revolt of the Flemish provinces.

Pieter Lanchals, in fact, was a close friend and advisor to Archduke Maximilian of Augsburg, husband of Duchess Mary of Burgundy. When the Flemish provinces rebelled against the Archduke in 1488, Lanchals was imprisoned and beheaded in the Market Square of Bruges, and Maximilian was forced to witness his friend’s execution.

Legend says the archduke cursed the city in a very peculiar way: since Lanchlas’ crest was a swan, he compelled the city to keep swans in the Reie River.

They are not friendly. They’re not friendly at all.

4.2. What’s a beguine anyway?

We still use the word, in Italy, to indicate an unmarried woman that’s unhealthily connected to the church and usually doesn’t have a life of her own: she’s generally nosy, not very attractive, and judgmental.

As it turns out, this is the legacy of a successful discrediting campaign.

In her wonderful Heretics: Stories of Women Who Reflect, Dare and Resist, Adriana Valerio dedicates a section to the beguines in Chapter 3 on the spiritual unrest stirring in the Middle Ages and involving women of all social classes.

Popular religiosity and reform movements spreading through Europe during the Middle Ages, were not so much focused on theological disputes when they involved women — contrary to what happened in other, more masculine contexts — but instead focused on the search for a way of life that was more adherent to the Gospel and the example of the first communities described in the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 4:32-35).

All the believers were one in heart and mind. No one claimed that any of their possessions was their own, but they shared everything they had. With great power the apostles continued to testify to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus. And God’s grace was so powerfully at work in them all that there were no needy persons among them. For from time to time those who owned land or houses sold them, brought the money from the sales and put it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to anyone who had need.

Many women believed Christianity had to be lived in poverty, charity and apostolate, and joined reflection groups who were meditating on the pages of the Bible.

Around 1091, Bernard of Constance was already pointing out how many laypersons, both women and men, wanted to shape a religious experience that recalled the proto Christian communities, and — almost two centuries later, in 1274 — a concerned Gilbert of Tournai told the Council of bishops fathered in Lyons about the phenomenon of the mulierculae (“pseudo-women”) called “beghine” who, in northern France and Belgium, dared to read and comment publicly on the Bible in the vernacular, attracted by the subtilitates et novitates of theological questions.

That’s the first account we have of the word used in connection to these groups of women, and you can already see the contempt reeking from the diminishing term “mulierculae”.

The name’s etymology is uncertain, and some trace it back to the Old Saxon beggem, meaning “to pray”.

Among us are the mulierculae called beghines, some of whom are noted for their subtlety and openness to novelty. They possess in the common Gallic idiom the mysteries of the Scriptures, mysteries that are barely accessible to Scripture specialists. They read them in public, without respect, in conventicles, in squares.

According to Valerio, it’s not easy to reconstruct the complex and variegated world of the beguines, both because of the differentiated experiences that are hidden under such a generic or equivocal name, and because of the temporal extent of the phenomenon (from the XII to the XV century), and finally because of its geographical extension.

Appearing in the Netherlands at the end of the 1100s, this peculiar female presence spread rapidly, especially in the Rhineland, Provence and central-northern Italy, and was immediately perceived as a novelty in the panorama of religious movements of the time, generating astonishment and more than a little apprehension in the ecclesiastical hierarchies.

These women, in fact, wanted to experience a life of faith that was not closed within monastic walls but, on the contrary, open to the needs of the society in which they were deeply involved: they were economically autonomous because they carried out manual labour (in Bruges it was lacework), they engaged in charitable works aimed at the poorest and most marginalised, they were connected to other women with whom they shared the need to pray and study sacred texts, and they were united by an intense mystical experience that they sometimes put down in writing in their mother tongue.

For the beguines, the main focus was the problematic reconciliation between ecclesiastical practice, marked by economic interests and power, and the message of Jesus, which called for choices of poverty and participation in the condition of the poorer classes of society. The search for alternative ways of life more in line with the evangelical spirit and the need to lead a simple existence like that of the primitive Church became a priority rule of life compared to the obedience owed to the ministers of the cult.

Many of them were considered mentors by disciples who gathered around them, fascinated by the freedom with which they spoke and lived. Ida of Nivelles, Maria of Oignies, Odilia of Liège, Hadewijch of Antwerp, Ida of Gorsleeuw, Beatrice of Nazareth of Lier, Matilda of Magdeburg, and Margaret Porete are just some of the names of these magistraesses who devoted themselves to theology studies between the XII and XIV centuries.

Their literary works, whether they were treatises, letters or poems, were composed in vernacular languages and expressed with the freshness of their mother tongue an intense religious experience usually difficult to communicate through the more algid Latin. This is why women’s writing revolutionised the approach of theological narration.

To a Church preaching images of power, like an all-powerful God and a judging Christ, the lives of these women opposed a communion of intentions, the image of a loving, maternal God and the fragility of a Son who had to be cared for, loved and in whom to recognise and share the weak human condition: a model of a poor community sharing in the misery of others.

Matilda of Magdeburg, for instance, writes The Flowing Light of Divinity to explore the maternal side of God and gives us a vibrant narration of the nativity, where she explores in narrative form what Maria might have done with the gold, incense and myrrh received from the three wise kings. In light of the intellectual movement of the beguines, her answer (in the words of Mary) is obvious:

With the gift brought to my Child [Mary replied] I provided for all those whose need I truly knew. They were impoverished orphans and innocent virgins who were thus able to marry, escaping the risk of being killed by stoning. And also the abandoned sick and the old in old age were to use the gifts reserved for them.

Sharing was essential for the beguines, as was being autonomous in work, even though their ultimate goal was to transcend themselves and merge with God in a union that excluded any intermediary (sine medio).

These women, driven to express their faith by appropriating unusual spaces of freedom, formed spontaneous aggregations that led to the creation of structures called beguinages, small female communities such as the one in Bruges, that aspired to lead independent and self-sufficient lives.

For these reasons, they attracted suspect from the ecclesiastical hierarchy, which had difficulty controlling such a variegated and dynamic movement and, above all, could not accept the independence of this original spiritual path: a lay and autonomous path that attempted to reconcile personal growth with a community experience of sharing, study and work, and that was so attentive to the themes of renovation many advocated for the Church.

The intervention of the ecclesiastical authorities decided to push these women towards a more controlled monastic life. The strategy, already deployed by Innocent III, was to support the nascent Mendicant Orders (Dominicans and Franciscans) who, by welcoming women who wished to lead a poor and evangelical life, directed them to submit to hierarchical, patriarchal authority.

In this way, discontent could be stemmed by bringing dangerous anxieties for change back within orthodoxy on permissible paths. The Humiliati order, for example, was judged heretical at the end of the XII century but it was reintegrated and recompacted within thirty years, and the downsizing of women’s role played a big part in their readmission: in his Confessio Fidei of 1210, Bernard the First had to swear that no women would take part in preaching.

Matilda of Magdeburg herself, after the synod had taken action against the beguines, followed the indications of the Dominican fathers and entered the monastery of Helfta in 1271.

With the decretal Periculoso et detestabili of 1298, the infamous Boniface VIII steered women towards nunneries, not tolerating any outside activity that was not under the control of the authorities: he established perpetual seclusion for nuns and intensified the work of regularisation — through teaching, preaching and spiritual direction — and repression, strengthening the work of the Inquisition tribunal that had already been active for a century.

In 1311, the Council of Vienna condemned the “errors” of the beguines. The most illustrious victim was Margaret Porete, but that’s another story, and shall be told another time.

No Comments