In Chapter VIII of Alice in Wonderland, Alice finally gets back to where she started through a door in a treetrunk and eventually arrives in the beautiful garden she had seen through the keyhole of the first chapters. There, we meet one of the most iconic characters of the book, right alongside the White Rabbit, the Caterpillar, the Cheshire Cat and the Mad Hatter: the Queen of Hearts.

In his Tenniel Illustrations to the “Alice” Books, Michael Hancher analyzes the drawings to the first edition of the book (not considering Carroll’s own sketches for Alice Underground) and gets in considerable depth around the illustration for the meeting scene, particularly when it comes to the iconography of the cards, so let’s start from there.

1889: John Tenniel

We get no clear description of the Queen, in the book: just her furious attitude. In his article “Alice on the Stage”, published on The Theatre in April 1887, it’s Carroll himself who provides us with an insight on the significance of her erratic behaviour:

I pictured to myself the Queen of Hearts as a sort of embodiement of ungovernable passions, a blind and aimless fury.

But how do we picture the Queen of Hearts?

It stands to reason that, as Tenniel suggests, our minds go to the traditional illustrations on playing cards, but here lies the trick: what is the traditional figure for the Queen of Hearts and what are her attributes?

When we are talking about traditional playing cards, lots of us mean the French deck, specifically the so-called Paris pattern. In this deck, known as the portrait officiel since 1780 or around that, each figure is associated to a historical and mythical figure and guess who the Queen of Hearts is associated with?

Judith

Yup. The biblical Judith, the beautiful widow who teaches everybody a lesson by infiltrating the camp of the Assyrian general Holofernes and, after gaining his trust, she gets him drunk and cuts his head off, bringing it back to her countrymen and rallying them to fight the invaders. She’s one of the favourite subjects in the history of art, but you might remember her painting by Artemisia Gentileschi, often compared with the same topic by Caravaggio, in which you can clearly see the kind of feelings Artemisia had towards a certain kind of men, in that period of her life.

Veiled in blu, the traditional representation of the Queen of Hearts in the French Portrait holds a red flower in her hands and a red drop on it seems to be signifying a drop of blood. However, this is not the oldest representation of the Queen nor, probably, the one you have in mind.

The English pattern was affirmed, similarly to what happened in France, when the production of playing cards was banned and only approved cards (which had paid a tax) could be manufactured. In France, this happened in the XIX Century. In France, this dates back to 1628, when importing foreign cards was prohibited. This is when we start seeing a more stern design of cards, a result of Charles Goodall and Son’s reworking the original cards from Ruen. According to tradition, the English Queen of Hearts is Elizabeth of York, the unfortunate wife of King Henry VII we can see in Shakespeare’s Richard III.

If you take a look at one of her portraits, currently Hampton Court Palace, you can clearly see why one might think that.

Other notable Queen of Hearts are in the beautiful Vienna Pattern, heavily influenced by the Lyonnais pattern. My favourite is related to these: it’s the Hungarian pattern. According to The Playing Card and Its History Thought by Benő Zsoldos, it was published before 1848 and illustrated by the painter József Schneider, who took the lower and upper figures from Friedrich Schiller’s play Wilhelm Tell in 1804. The play, which was performed in Hungary for the first time in 1827, inspired József Schneider a first deck of cards in 1835, cut in copper and richly detailed in red, scarlet, blue, and brown. After the defeat of the War of Independence in 1848-49, the cards were confiscated by the Austrian government, but the Piatnik company started producing the Hungarian Tell card back around 1865.

Tenniel of course takes after the English Portrait, when giving his Queen of Hearts the traditional headgear and overcoat, although the holds no flower as that would have been considered too gentle. As Michael Hancher points out, however, the details of her dress are not the ones of the Queen of Hearts, but they come from a different card: the Queen of Spades, a figure traditionally associated with death, particularly the neck of her dress. The Queen of Spades is the one single card you have to avoid taking when playing Hearts, with is rather peculiar.

A rather different Queen of Hearts appeared in a traditional nursery rhyme originally published in European Magazine in April 1782 but presumably much older.

The Queen of Hearts

She made some tarts,

All on a summer’s day;

The Knave of Hearts

He stole those tarts,

And took them clean away.

The King of Hearts

Called for the tarts,

And beat the knave full sore;

The Knave of Hearts

Brought back the tarts,

And vowed he’d steal no more.

This has clearly nothing to do with us: not only we cannot picture Alice’s Queen in the kitchen, but the King seems to amount to very little indeed, in our story. This is probably why sometimes a tremendous mess is made between the Queen of Hearts, the playing cards for Wonderland, and the Red Queen of Chess in Through the Mirror. It’s worth mentioning, however, that the Queen can be worth more than the King in a card game when the throne of England is occupied by a woman. Queen Victoria was on the throne when Alice in Wonderland came out, so I would say this rule clearly applies.

The unflattering representation Tenniel does of the full-faced, not particularly charming queen also fits her description and Tenniel, as any caricaturist, was bound to be a bit of an asshole. This allegedly never stopped the Queen from enjoying the book tremendously.

But what are the other representations of the iconic queen and how do they differ?

As usual, it would be impossible for me to provide you with a comprehensive collection, so you’ll have to settle for my personal selection.

1907: Arthur Rackham

As we have seen in the post about the three unfortunate gardeners, Arthur Rackham is by any means no more charming than Tenniel and the rest of the band, while portraying the ill-tempered Queen. He gives us her character at least three times: with the gardeners, at the croquet game (below) and in court.

In the particular one below, we get a chance to appreciate not only the details Rackham bestows upon her but also the ones on the King of Spades and the rest of the court. There’s also a black Queen in the background, as traditional as they get, and Alice is at the border of the picture, seemingly conversing with the White Rabbit.

1907:Charles Robinson

One of the best efforts in illustrating the Queen of Hearts as close as possible to the traditional design of playing cards is made, in my opinion, by Charles Robinson. In his amazing 1907 illustrations, we get a Queen whose traditional patterns are cleverly used to convey the sense of unrestlessness, of pure passion and anger. Below, you have the meeting with Alice, with the painted roses on the background and a row of lining-up clubs that are bearing the burden of conveying a bit of perspective to the scene. The white rabbit is peeking from the background and raised insignia are suggesting the Queen of Diamonds and, perhaps, a King of Clubs.

But this was not enough and Robinson gives us another take of the Queen, in the following scene of the quarrel at the croquet game, and I think it’s worth showing it here, instead of the next post. He decides to use the same device but turns the Queen sideways. We can then admire her profile, the headdress and the detail of the almost mermaid-like tail of her dress. Since we’re engaging with those playing cards in Alice’s journey, it’s really clever that he decides to show us this unusual perspective, a perspective we would never see on a playing card.

The third one is, of course, a three-quarter shot. We know her, now, we have the full comprehension of her dimensions, and we are not surprised while she quarrels with the King and the Executioner: she has become a proper character, way more than a figure painted on a card.

1911: Philip Lyford

A stern sideways position is recuperated by this American author in his illustration for a reduced retelling penned by Elizabeth Lewis. Alice doesn’t seem to be bothered much by the presence of the Queen, nor is she in the book, to be honest, but she’s significantly less angry. The Queen, however, displays the same angry discontent and is wielding a sceptre. J.B. Lippincott Co. copyrighted this edition in 1913, 1914, and 1917

1922: Thomas Robinson

In his monochrome illustration, Thomas Robinson takes his time to show us not only the details of her fur-trimmed dress, her belt and her crown but particularly her hair, a renaissance-style bun on top of the ear that would make Queen Amidala blush.

1949: Adrienne Segur

Do you remember Adrienne Segur? I had a chance of talking about her when we saw the White Rabbit’s house and on that occasion, I could salvage a post that was present on a blog that went down, like a proper archaeologist. She also gives us a wonderful picture of the Queen of Hearts, walking around with Alice during their croquet game. I wanted to a proper post on the game, but this Queen is too particular not to feature in this post. I’m only sad I couldn’t find a larger of better picture.

1981: Yefrem Pruzhansky

Back in 1891, Yefrem Pruzhansky directed an animated version of Alice in Wonderland in Soviet Ukraine, employing a mind-blowing mix of different techniques. It featured classical music, pieces from Luigi Boccherini and Ottorino Respighi, alongside an original score composed by Andrzej Korzyński. From that piece, we have this incredible shot of the Queen of Hearts, in a grand display of leadership, showing by doing. This is loaded from the Alicismo tumblr, as WordPress doesn’t allow me gifs. For reasons that are way beyond my comprehension.

1982: Barry Moser

Barry Moser’s effort to illustrate Alice in Wonderland won him the 1983 American Book Award for Design and Illustration and you can clearly see why. Visionary to say the least, he gives us a dark-haired Alice and creatures significantly influenced by the most eccentric illustrators, Segur not excluded. His renowned for his portraits of Alice, Alice after the fall and Alice 40 years old (you can see them here). We saw his nightmarish caterpillar, if you remember that. If you forgot, just tell me how you did that, because it’s been haunting my nightmares ever since.

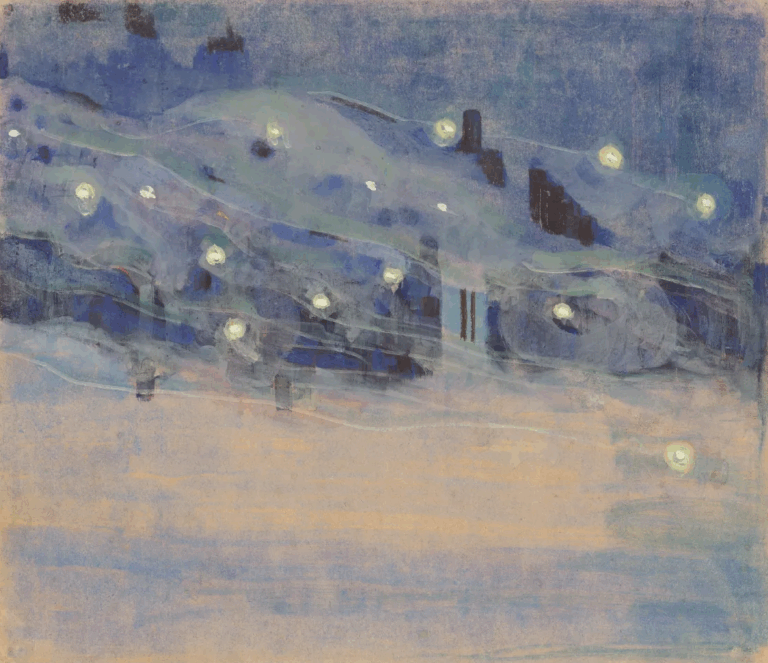

Moser prepares us by showing a beautiful, beautiful garden that’s bound to allure us and draw us through the mysterious door.

Giving his caterpillar and the rest of his stuff, and the somewhat ominous creatures lurking from the top of the pedestals, you might imagine what comes next. The Queen is ominous, nothing short of a broodmother from Dragon Age: her head is framed with laces and frocks, she even has a rose on top of her head, but this doesn’t make her any more charming.

1990: Greg Hildebrandt

If my favourite playing cards are the Hungarian one and the Vienna one, it is only normal that one of my favourite illustrations of the Queen would be the one by Greg Hildebrandt. The choice for the belt is not particularly kind towards her majesty’s waist and figure, but the headdress and the rest of the robes are just amazing.

1995: Nick Hewetson

Nick Hewetson […]

2014: Maria Kolyshkina

One of the most amazing contemporary authors to work on Alice in Wonderland is without any doubt the Russian Maria Kolyshkina. You can see her project and the complete book here: I’m completely in love with all her work, particularly her usage of cards as surrealistic clothing for all her characters, and I’m particularly in love with her Queen of Hearts, towering on top of what becomes a long table like the tea-party one.

2016: Lisbeth Zwerger

Lisbeth Zwerger’s illustrated edition is one of her finest works (you can find it here), alongside a beautiful Swan Lake, The Little Mermaid, The Night Before Christmas, The Pied Piper of Hamelin, and Tales from the Brothers Grimm. She was awarded the Hans Christian Andersen Medal in 1990. Her illustration of the Queen of Hearts rightfully makes the front cover of the book, with a flower in her hand as tradition requires and wrapped in her own card like a mantle. Her crown seems to be cut out of paper too and both she and Alice seem to be observing the cadavers of the three poor gardeners.

No Comments