Last week, I gave you a little bit of insight on The Little Mermad, probably the work by Hans Christian Andersen that I detest the most (although it’s hard to choose between that and The Little Match Girl). This week I thought I should balance that by writing something on a tale I actually like, about another water maiden Arthur Rackham got the chance to illustrate (if you remember, Rackham is the whole reason we got into this mess in the first place): Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué’s Undine.

A little bit about the author first

Friedrich Heinrich Karl, Baron de la Motte Fouqué is a guy who doesn’t get nearly enough credit. Fouqué was born from a French family, and they had moved to Germany after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, which had granted rights to the Huguenots within Catholic France, marking the end of a religious civil war that had plagued the Country for several decades, between 1562 and 1598. Particularly, the edict had been revoked by Louis XIV with the Edict of Fontainebleau, October 1685, and prompted the exodus of several Protestant families. The edict and its effects is comparable to the 1492 Alhambra Decree, which ordered the Expulsion of Jews from Spain and the Expulsion of the Moriscos in 1609.

By the time Friedrich was born, in 1777 at Brandenburg an der Havel, his family had a well-established career in the Prussian army: his grandfather, Heinrich August, had been a general under Frederick II the Great, King of Prussia, and his father was a Prussian officer too. Eventually, even Friedrich took up a military career, and he participated in the Rhine campaign of 1794, but he retired in 1813 after being wounded in the battles of Lützen and Bautzen, and most of the rest of his life was devoted to writing.

He was a German Romantic at heart, with a devoted fascination for Norse poetry and folklore, to the point that in 1810 he wrote a dramatic trilogy, The Hero of the North, about Sigurd and his slaying of the Dragon. The trilogy was received with a great success, and had a great influence on the other versions of the story yet to come, including Richard Wagner‘s.

Ohe! Ohe! Horrible dragon, O swallow me not! Spare the life of poor Loge.

Althoug being his first work, this prety much sums up his career: the guy was incredibly influential, in his time, and then he fell from grace. By the end of his career, his works had been labeled as “stories for children” and he died almost forgotten. Sic transit gloria mundi. Which prety much translates to “sometimes, people are assholes”.

Other works

Aside from Undine, which we’ll get to in a minute, he worked a lot around the themes of love and chivalry and lots of his works were translated in English: Minstrel Love (translated in 1821), The Magic Ring (translated in 1825), Aslauga’s Knight (translated 1827), The Two Captains (translated in 1843, the year Fuqué died) and Thiodolf, the Icelander (written in 1815 and translated in 1845). On top of Wagner and Andersen, his work inspired people like Robert Louis Stevenson, who wrote his own version of one of Fouqué’s stories in his The Bottle Imp, proposing a Hawaiian setting.

Another tale, The Magic Ring, has lengthily been debated as one of the sources for J.R.R. Tolkien’s One Ring. It was published in 1813 and, just as it happened with other tales, it met with instant and great success, only to be forgotten few decades later. On the relationship between this tale and Tolkien, you have a rather superficial article here, and there’s mention of it in an article by Terri Windling. I couldn’t find the original one, but you can re-translate an Italian translation that was done here. The same translation also appeared here and it was done by Nicola Iarocci.

The first page of an English edition for “The Magic Ring” as seen here.

His second most influential work other than Undine, often proposed together with it in foreign translations, is Sintram and his Companion, the last of a cycle of four in which it was meant to represent winter, while Undine was the spring. The story is more chilling than Andersen’s Snow Queen (one of the tales I actually do like) and is set in Drontheim and the surrounding mountains, during the late Middle Ages. Just as much as Undine, the story has a strong religious background but, as opposed to The Little Mermaid, it manages to treat it with a lighter and more delicate touch.

Sintram is a young boy, caught in between a father who professes a gruesome pagan cult, called Biörn in a homage to the Norse tales Fouqué was so fond of, and a Christian mother called Verena, who had the bright idea lf locking herself up in a convent, leaving her son, because that’s what pious mothers do. To no one’s surprise, the boy is plagued by visons of evil spirits, including but not limited to a pilgrim with human bones sewed to his clothes, and an ugly shapeshifting dwarf called Kleinmeister. So it’s basically the story of a boy who has imaginary friends because his parents are at war with each other.

Among other authors, the tale had a tremendous influence on William Morris himself.

You can read some insights on the story here, by the end. The article was one of my main sources for Undine as well.

Undine

Similarly to The Little Mermaid, which was inspired by Fouqué’s tale, Undine is the story of a water maiden who wants to marry a knight, an act that would grant her a mortal soul. There’s a beautiful retelling you can find here.

Many hundreds of years ago, a fisherman lived between two supernatural worlds. His little cottage sat between a wood that was thick, tangled and haunted, and a lake that was the home to the water nymphs. By and large, the humans and the magical beings pretended not to notice each other.

Undine was one of the most influential tales on English literature during the Victorian and Edwardian period, and not only since it became something for children, It is both quoted by George MacDonald in his Fantastic Imagination and by Lafcadio Hearn in his “The Value of Supernatural in Fiction”, and C.S. Lewis praised it in his “The Discarded Image”, an essay on Medieval and Renaissance literature.

Were I asked, what is a fairytale? I should reply, Read Undine: that is a fairytale … of all fairytales I know, I think Undine the most beautiful. (George MacDonald, The Fantastic Imagination)

It was adapted in different opera’s and ballets.

1816: E. T. A. Hoffmann

The first and one of the most famous adaptations of Undine into an opera is probably Hoffmann’s Undine, a three-act opera with lengthy portions of spoken dialogue for which Fouqué himself wrote the libretto. It premiered at the Königliches Schauspielhaus in Berlin on August, 3rd and it was considered to be one of Hoffmann’s greatest success, although to this day it certainly isn’t his most famous work.

Undine and Bertalda are both sopranos, while the knight is a baritone (thus breaking the glorious tradition of any opera being the tenor loving a soprano while the baritone opposes them).

In a letter to a friend, Hoffmann reported that the inspiration for the music of Undine was mostly around the elements evoked in the story and, just as we’ll see for Rackham, the bad weather is one of the main sources:

“The storm, the rain, the pouring water constantly reminded me of Uncle Kühleborn, whom I often admonished in a loud voice through my Gothic window to be quiet, and there he was so naughty not to ask anything about me, I decided to banish him with the mysterious characters that are called notes! – In other words: Undine should give me wonderful material for an opera!”

(E.T.A. Hoffmann, Letter to Julius Eduard Hitzig – July 1st, 1812)

The stage designs were developed by Carl Friedrich Schinkel, a Prussian architect, city planner, and painter who had also done the perennial star-spangled backdrop for the Queen of the Night in Mozart‘s The Magic Flute, one of the elements rarely missing in any of today’s renditions. As an architect, he was working in the Gothic Revival movement, so he most likely had a field day with the German medieval settings of Undine. He designed seven new decorations, while three other came from the theatre storage. The most famous of them is probably the water palace.

Costumes were mostly based on paintings by Hans Holbein the Younger, a renaissance painter who famously worked under the patronage of Queen Anne Boleyn and Thomas Cromwell, and Lucas Cranach the Elder, court painter for the Electors of Saxony. It is not uncommon to find Holbein and Cranach as main influences of medieval-inspired designs: there’s even a current called Holbeinesque jewellery, in the Gothic Revival movement, which designed and manufactured jewellery and other accessories as they were portrayed in Tudor era paintings.

“In terms of beauty and fantastic charm, the stage, as far as we know it, has not yet done anything similar to the eye”

(Ludwig Rellstab in a 1841 review of Undine)

1843: Cesare Pugni

Following another adaptation made in 1830 by one Christian Friedrich Johann Girschner, the second significant adaptation of Undine was a ballet composed by Cesare Pugni with a famous choreography by Jules Perrot. The ballet was called Ondine, ou La naïade, and it premiered in London on June, 22nd.

Cesare Pugni, the composer, was an Italian-born composer, who worked in London between 1843 and 1850, composing for Her Majesty’s Theatre, and in St. Petersburg between 1850 and 1870, composing for the Imperial Theatres. His most famous works are La Esmeralda (1844), an incidental dance known as the Satanella pas de deux (1859), The Little Humpbacked Horse (1864), and some additional music for the ballet Le Corsaire, but Ondine is certainly top of the list.

Jules-Joseph Perrot was a dancer and choreographer who would go on and became Ballet Master of the Imperial Ballet itself, after doing choreographies for lots of Pugni’s works, including La Esmeralda. His most famous work is certainly Giselle with music by Jean Coralli.

Together, and inspired by Fouqué’s Undine, they created a ballet in three acts and six scenes, and dedicated it to Princess Augusta of Hesse-Kassel, but Perrot would later restage the ballet with a new title, La naïade et le pêcheur, and it’s the title it has been known as ever since.

This scenery design, signed “Hodgkin”, is preserved at the British Museum.

The premiere saw the ballet of Her Majesty’s Theatre, with the famed Italian dancer and choreographer Fanny Cerrito in the title role and Jules Perrot himself playing the part of her lover, who in the ballet is not a knight but a fisherman.

The original scenery was designed by William Grieve, who also will work on the Esmeralda.

Nathaniel Currier, Lithograph of the ballerina Carlotta Grisi performing the Pas de l’ombre in Ondine (1843).

Around 1851, the production was revived and extensively expanded, with new music composed by Pugni for the Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre, where it premiered in February. The most famous of these new editions however occurred in July at Peterhof Palace, where a stage was erected above the waters of the lake near the Ozerky Pavilion and the ballet was performed in honour of Olga Nikolaevna, the daughter of the Czar.

Aside from the expansions made by Pugni himself, the music was later revised by Ludwig Minkus, for a 1874 rendition, and by Riccardo Drigo for a 1892 edition.

1845: Albert Lortzing

After the ballet, Undine came back as an opera thanks to the efforts of Albert Lortzing, who adapted it into a four-act opera. The work was part of a general revival of attention towards Fouqué’s works, after his death in oblivion in 1843, and it was first performed in April at the Magdeburg’s Municipal Theatre, in April.

Both Bertalda and Undine are a soprano in this opera too, but the knight is a tenor, in a more traditional choice. You have a nice analysis of the opera here.

1869: Pyotr Tchaikovsky

One of the most mysterious operas, however, is an opera in three acts written by Tchaikovsky with a libretto by Vladimir Sollogub.

The work has a rather interesting history, something fit for fiction: it was composed in 1869, during the span of six months from January to July, but in 1873 Tchaikovsky decided the score had to be destroyed and he preserved only a few parts. The opera has never been performed in its entirety and no record survives of how it was supposed to sound like. Aside from the Overture, the only surviving piexces are an aria sang by Undine in which she sings her communion with the water elements (“Waterfall, my uncle, streamlet, my brother”), a chorus to accompany the flood (“Help, help! Our stream is raging”), a duet between Undine and her knight (“O happiness, O blessed moment”) and another chorus with Undine, Bertalda and the knight chiming in (“O hours of death”). In an even more traditional choice of roles, Undine is a soprano, the knight is a tenor and Bertalda is a mezzo-soprano, while the fisherman and Bertalda’s father the Duke are both a bass.

1901: Dvořák

Antonín Dvořák‘s opera Rusalka is probably the most complex of these works, if not the most famous, as it incorporates both elements from Fouqué’s Undine and elements from Andersen’s “Little Mermaid”. The Czech libretto, written by the poet Jaroslav Kvapil, also took up as inspiration lots of local folk tales featuring water spirits, such as the fairy tales of Karel Jaromír Erben (mostly the collection Kytice) and Božena Němcová‘s own fairy-stories. Up to these days, it’s considered to be one of the most successful Czech operas of all times.

1904: Prokofiev

Another supposedly interesting work we’ll never get to hear is an opera, based on Undine, Sergei Prokofiev has allegedly been working on between 1904 and 1907. The libretto was supposedly written by one A.M. Kilštedt, poet, but you find records of him/her only in association with this unpublished work, so I have to wonder whether it’s not a typo that spread and the name was supposed to be different.

It was Prokofiev’s first opera and he started writing it while he was at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, but he never got around to finish it. Apparently it was really good too.

1908: Ravel

It’s not really a full work, but Maurice Ravel dedicated a movement to Undine in his Gaspard de la nuit, a suite of piano pieces in three movements based on the collection of prose-poems Gaspard de la Nuit – Fantaisies à la manière de Rembrandt et de Callot by Aloysius Bertrand (1836). The movement dedicated to our favourite water nymph is the first one, and it’s filled with water sounds which might remind you of Ravel’s own Jeux d’eau (1901). The piece has five main melodies.

1911: Debussy

Another work that’s not strictly an opera not a ballet but still is worth mentioning is Claude Debussy‘s Piano Prelude inspired by Undine and written between 1911 and 1913. More than inspired from Fouqué’s work, it’s one of the (many many many) French works that were derived from the character of Mélisande from Maurice Maeterlinck‘s symbolist play Pelléas et Mélisande.

Arthur Rackham’s edition

Arthur Rackham got to illustrate Undine in 1909 and it’s without any doubt one of the highest peaks of his career. The edition was jointly published in London by Heinemann and in New York by Doubleday, Page and Co. Rackham did fifteen illustrations in colour and a huge amount of black and white line works. In 1919 he came back to the topic, as he often did.

His coloured plates mostly revolve around four kinds of subjects: the knight, Bertalda and Undine herself, though Undine – as we’ll see in a minute – comes in two distinct manifestations: the innocent maiden we’re used to see and a significantly more impish version in which the water nymph takes up the facial expressions a trickster from Norse mythology. In the black and white illustrations, he also adds more subjects, such as sceneries of the castle and forest, and a lot of creatures both from the water and from the forest itself.

The many faces of Undine

The first times we see our heroine, aside from the illustrations we have of her childhood, she’s looking straight at us, and she means business. Rackham decides to place her outside the fisherman’s window, with the nets distinctively separating her from the water on the right side of the illustration, but it’s clear enough that they’re cut from the same fabric: her hair on the right flows like the waves, and so does her gown, but on her left he decides to draw her with a more human braid. Though she’s offering her shoulders to the house, we’re starting to get a glimpse of the creature’s conflicted nature: she’s not the temptress rising from the waves to drown mortals or to seduce men into forfeiting their soul for her, but she’s a being longing for humanity, a feature we have seen (mis)represented by Hans Christian Andersen in his Little Mermaid.

The second time we see her, we see her through the knight’s eyes: she’s sitting on an isle in the middle of a flooding river, one hand on the rocks and the other one parting the branches of the tree. The weather is not good, it seems it never is in these illustrations, only this time her provocative look is both at us and at the knight, with whose eyes we’re seeing the scene. Her hair is again divided in half, one half following the wild flow of the river and wind, and the other half braided in a more composed look.

Arthur Rackham, “He saw by the moonlight momentarily unveiled, a little island encircled by the flood; & there under the branches of the overhanging trees was Undine” (Undine, Plate 5)

The troubleful looks is kept also in the following plates, immediately afterwards, when the knight goes to “rescue her”. Regardless of the naturalistic attention he gives us with the evil-faced trees and the plants of the riverside, something we’re really used to by now, you have to appreciate the attention to detail and consistency to Undine’s costume, with the gown and corset, and the dotted sash on her waist.

Arthur Rackham, “The Knight took the beautiful girl in his arms & bore her over the narrow space where the stream had divided her little island from the shore“

The more we progress with the tale, however, the more she changes from the impish creature to a more playful and eventually melancholic being. The duality seems to be gone and, though she’s always depicted with a strong connection to the winds and nature, even if she’ll never be the composed lady her rival Bertalda is going to be, she inspires more and more sympathy. And she even changes her dress slightly, putting flowers on her gown.

Arthur Rackham, “When the storm threatened to burst over their heads, she uttered a laughing reproof to the clouds. “Come, come,” sayeth she, “look to it that you wet us not.” (Undine, Plate 9)

She’s even more human, more vulnerable, during her travel through the forest, when she meets her uncle. Compared to the encounter we see between the little mermaid and her sisters in Hans Christian Adersen’s tale, where the waterland gets in touch in a very delicate and melancholic way as if the two worlds are prevented to really touch and the only point of conjunction is our heroine, here the Undine’s family is a little more vocal in trying to get her back. The way Rackham designs the guide splitting into an angry water spirit, including the earth turning to waves under his feet, is one of my favourite things of the whole set of illustrations.

Arthur Rackham, “Little niece,” said Kuhleborn, “forgot not that I am here with thee as a guide.” (Undine, Plate 10)

Anyway, the next time we see her commune with her element, she’s significantly changed (even if the weather is not). The ornaments and accessories taken up from her life on shore are still showing, but they’ll soon melt away as she stretches one last time and then vanishes in the deep waters of the big river.

Her farewell is certainly more melancholic: the impish and playful look is gone, replaced by a melancholic one, and her hair isn’t asymmetrical anymore. The courtly ornaments she showed in the previous illustration, both around her neck and her waist, melted away in turquoise fabric.

On a side note, it’s worth a show of appreciation to the weeds and fishes in the background, forming a sort of underwater tree.

Undine also appears in lots of black and white illustrations, some of them almost as structured as the color plates, like the one I give you below.

Again, there’s a difference between the Undine in the first steps of the story (above) and the more tragical figure she becomes by the end of it (below).

Bertalda

The other female character Rackham takes his time to portray is Bertalda, Undine’s rival and the girl the knight eventually marries. She’s sort of the opposite of Undine: while our water maiden is fair-haired and always portrayed in the midst of agitated elements, the first time we see Bertalda she’s standing at the balcony of a castle overlooking a very German-looking town, with mountains at her back only stressing the stillness and composure of her position. Her hair is dark and combed symmetrically, but still Rackham goes out and has fun by putting a flower in it and by adding intricate details to her dress.

Even if she’s more static than Undine, her look towards us is far from being uninteresting.

We see her three times, and the second time we meet her she’s not happy. She’s undergoing a search not dissimilar to the one taking place during witches trials, where old women of the village were required to meticulously search the body of the alleged witch in order to find a mark or an insensitive spot, thought to be the Devil’s kiss.

Since she’s portrayed sideways, we have a chance to furtherly admire her hair, this time adorned with pearls, and the richness of her dress.

The scene resembles a lot the courtly atmospheres we can breath in Edmund Dulac’s illustrations to Cinderella or even in some of Rackham’s own illustrations to the same tale: on top of clothes and fabric textures, receiving a great deal of attention not only on Bertalda but on the women too, we can appreciate some interior details, from the checker motif on the grazed curtain to the wood texture, down to the window frame and the curtain next to it.

Arthur Rackham, “She hath a mark, like a violet, between her shoulders, & another like it on the instep of her left foot.” (Undine, Plate 12)

The third and last time, she’s in a situation that would inspire Disney’s Snow White and her escape through the forest: she’s running, chased by the knotted and deformed silhouettes of those twisted, evil-faced trees we’re used to see in Rackham’s works. Oddly enough, some of Undine seems to have taken Bertalda, who started off as a far more static figure. She doesn’t have flowing hair, that would be tremendously out of character, but Rackham makes up for it by wrapping a drape around her hear and playing with the wind through that and through her mantle.

My favourite touch is the portion of sky among the trees, with an evil bird preying on our dame, pink clouds signalling that the dawn is approaching, and the far-away castle.

The Knight

The third major character repeatedly portrayed by Rackham is the knight, with whom we have already met while he was “rescuing” Undine. We pretty much always see him while he’s in trouble with some natural/supernatural element or the other (in Undine it doesn’t really make a difference). The second time we see him, he’s chasing a goblin.

Arthur Rackham, “He held up the gold piece, crying at each leap of his, ‘False gold! False coin! False coin!’ ”

…and the third time he’s reached the goblin (you can think of it as Chris Hemsworth playing the saxophone and listening to the saxophone, if you want).

The forest and its creatures

The fourth group of subjects we get from Rackham is far more explored in the black and white illustrations, aside from the Knight’s one we just saw.

Arthur Rackham, “At the back of the little tongue of land, there lay a fearsome forest right perilous to traverse“. (Undine)

There’s a lot of black and white illustrations on this subject, lots of them with a high decorative twist and incorporating both the humanoid creatures and botanical elements from the dark forest where they live.

The Castle

Another topic we barely touch in the colored plates and Rackham indulges quite a lot in the black and white works is an unusually architectural theme, unusual for him at least. It’s two illustrations I’m simply crazy about. One of them even features our sad heroine, though you can see how Rackham’s attention has switched to the human figure, going back to what he enjoys the most.

The Water and its Creatures

The last subject on which Rackham focuses has to do with the watery realm and its creatures other than Undine. There’s a beautiful color plate on Undine’s childhood…

…following the first time we see her, in the fisherman’s house. These two are pretty much the last two colored illustrations we were missing.

Arthur Rackham, “A beautiful little girl clad in rich garments stood there on the threshold smiling“. (Undine)

The watery realm, with the forest and its creatures, is another topic to which Rackham dedicates a lot of ink works and some of them are improperly used also in association with “The Little Mermaid”, like the one I give you below.

Other illustrated editions

Arthur Rackham’s edition is probably the most famous one, but there are other beautiful works by other artists, out there. I’ll try and give you a complete chronology, at least of the English editions. There’s a lot more out there, I’m sure. The most complete list of editions I was able to find, aside from the Project Gutenberg which is forbidden and sealed in Italy for highly idiotic reasons, it’s here.

1830: Sarah Elizabeth Major

The first work I was able to find in chronological order, way before the first English illustrated edition, was an etching by one Sarah Elizabeth Major, an artist I have very little information about. She’s also known as Sarah Elizabeth Thorn, accordingly to her biography, and she married the translator Richard Henry Major. The work we have is part of a set of prints donated to the British Museum by her husband. In the museum, three of them are scenes from Undine.

Bertalda standing on a steep ledge at right, leading a horse, waving at Huldbrand, swimming in a fast river at left, embracing Undine.

(reference page here)

A boat with five figures approaching from right on a lake, Bertalda standing on board, covering her eyes; the water-sprite Undine swimming in foreground, arranging her long hair; buildings on the opposite shore, hills in background, one with ruins of a castle.

(reference page here)

Huldbrand walking towards a waterfall, holding his sword over his shoulder, preparing to attack the old bearded spirit Kuhleborn; Undine, wearing a bridal gown and veil, riding a horse, followed on foot by Father Heilmann; forest behind.

(reference page here)

1845: John Tenniel and the Burns-Lumley edition

In the 1840s, the Scottish writer James Burns went into printing and published several German authors considered to be for children: specifically, he included Undine in his The Seasons (1843), alongside with Sintram and his Companions (a now lesser known tale by the same author of Undine, which greatly influenced the Arts and Crafts movement), and Aslauga’s Knight by Thomas Carlyle (often associated in English translations with the two works by de la Motte). The translation was done by an American, Thomas Tracy, and the book included illustrations done by an unknown artist. It was a shady operation, to say the least: the translation was used without Tracy’s consent or even knowledge. In 1845, Burns published another edition using an anonymous translation and eleven new illustrations by John Tenniel, whom you might remember as being the classic illustrator of Lewis Carroll’s works (he also did The Ingoldsby Legends and that’s why I talked about him here).

The illustrations for Undine were his first commission for a whole story, however, years before he became famous for Carroll and Dickens. Burns’s book with Tenniel’s illustrations was later republished by Edward Lumley and that edition is available here. There’s a surprisingly little amount of these illustrations available on-line (surprisingly little because Tenniel is quite renowned and the web is flooded with his Alices). There’s a frontispiece preserved at the British Museum, which was developed after an illustration by John Tenniel, an illustration from Chapter XV, another full-page plate and little else.

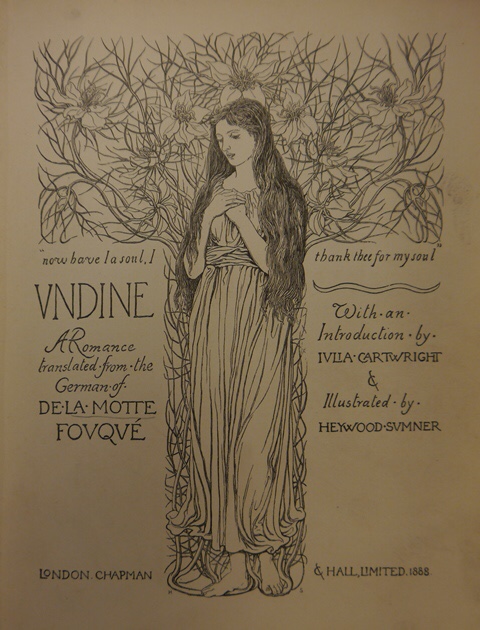

1888: George Heywood Maunoir Sumner and the Chapman Hall edition

Sumner was an arts and crafts designer, associate with William Morris in the 1880s and a member of both the Art Workers’ Guild. an association of architects promoting the “unity of all arts” and the Century Guild of Artists, an association mostly focused on preserving the authenticity of craftmanship. There’s an interesting biography of the artist here.

Sumner’s illustrations are both ornamental and interpretive, helping the reader to understand the text while entertaining his eye.

– Walter Crane, Of the Decorative Illustration of Books Old and New

He firmly believed art should be available to everybody, and in this attempt he helped founding the Fitzroy Picture Society, an amazing institution who aimed at producing colourful artworks and printing them cheaply so that they could liven up the walls of schools and hospitals.

His earliest publications were etchings, for books such as The Itchen Valley from Tichbourne to Southampton (1881) and The Avon from Naseby to Tewkesbury (1882) – which he wrote – and for John Richard de Capel Wise‘s The New Forest: its History and its Scenery, another account of the countryside which described customs of the New Forest in Hampshire. During his career, he developed illustrations for naturalistic and archaeological works, for folk songs and lore, and for children’s books. Undine was considered one of those, at the time, and he illustrated it for a 1888 edition for Chapman Hall. You can find news of one auction here, with a rich selection of pictures.

Illustration to Chapter XV, The Journey to Vienna, by Heywood Sumner.

1896: Gordon Browne and the Gardner-Darton edition

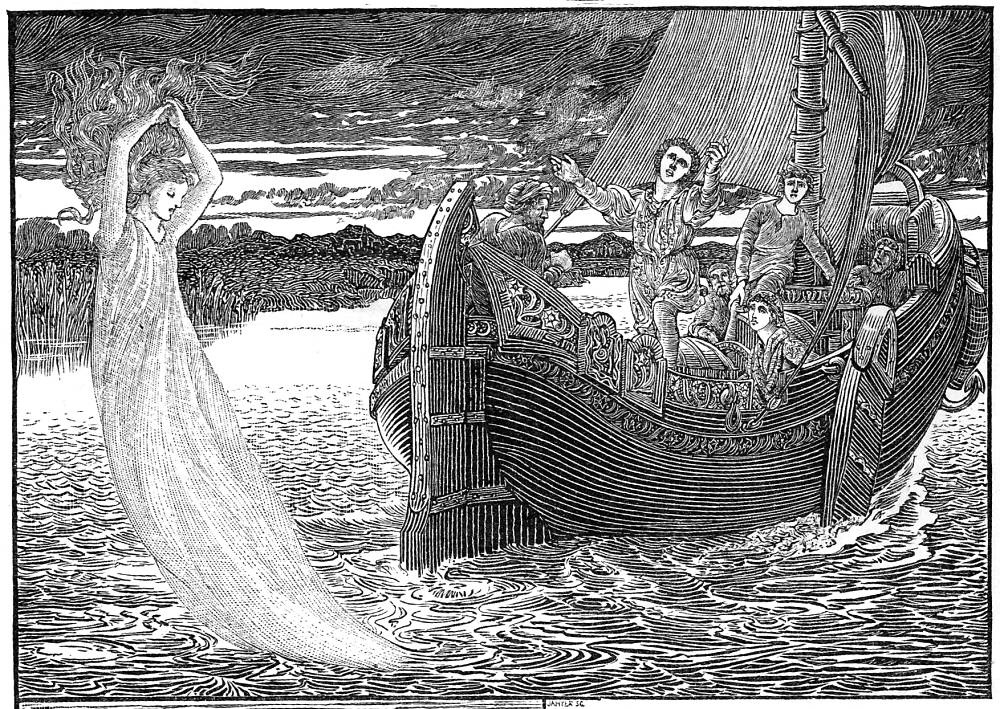

In 1896, W. Gardner, Darton & Co. published in London an English edition of Undine with an introduction by Charlotte M. Yonge, which would be later reissued several times in both Great Britain and the United States. This edition was accompanied by five full-page monochrome reproductions of paintings by Gordon Browne and some line-drawings.

Browne was a very prolific illustrator of children’s books, who did up to six books a year. Among lots of others, he did illustrations to works by Hans Christian Andersen (you know the guy and my love for him from the post on The Little Mermaid), R.M. Ballantyne (author of The Coral Island in 1857 and The Pirate City in 1874), Samuel Rutherford Crockett (a Scottish author who influenced Tolkien’s wolves in The Hobbit with his The Black Douglas: Browne co-illustrated with him his The Adventurer in Spain from 1903), the Countess d’Aulnoy (a prolific literary fairy tales writer), Daniel Defoe (the famed author of Robinson Crusoe, which Browne illustrated in a 1885 edition with over 100 drawings), Miguel de Cervantes (the equally beloved author of Don Quixote, that Browne illustrated in a 1921 New York edition), Washington Irving (another Scottish author and I already talked about him because Arthur Rackham illustrated some of his works too: Browne illustrated Rip Van Winkle in a beautiful 1887 edition you can see here), Andrew Lang (the famed author and anthropologist who collected a huge amount of folk tales and fairy-tales in his “coloured” books), Lord Tennyson (Browne illustrated a collection of poetry called The Poetical Works of Tennyson from 1899), Walter Scott, William Shakespeare, R.L. Stevenson, Jonathan Swift (Browne illustrated his Gulliver’s Travels again with over 100 designs), and William M. Thackeray.

Browne returned to Undine in 1912 in order to illustrate a children’s version, called The Story of Undine and edited by Mary Macleod, for Wells Gardner and Co. publishers (yes, same Gardner, different publisher).

1896: William E.F. Britten and the Lawrence-Bullen edition

In 1896, Lawrence and Bullen did a new edition of Undine with darker illustrations by William Edward Frank Britten, a British author who worked in a pre-Raphaelite style. The choice was aiming to appeal at more adult readers and, with a translation by Sir Edmund Gosse, the illustrations to this book were following his works on Algernon Charles Swinburne‘s Carols of the Year (1893) and Moira O’Neill‘s The Elf-Errant (1895). His sketches are far from being the neo-medieval, graceful depictions of courtly life we sometimes get from other authors: see for instance this naked, grieving Undine when the Count and Bertalda decide to marry.

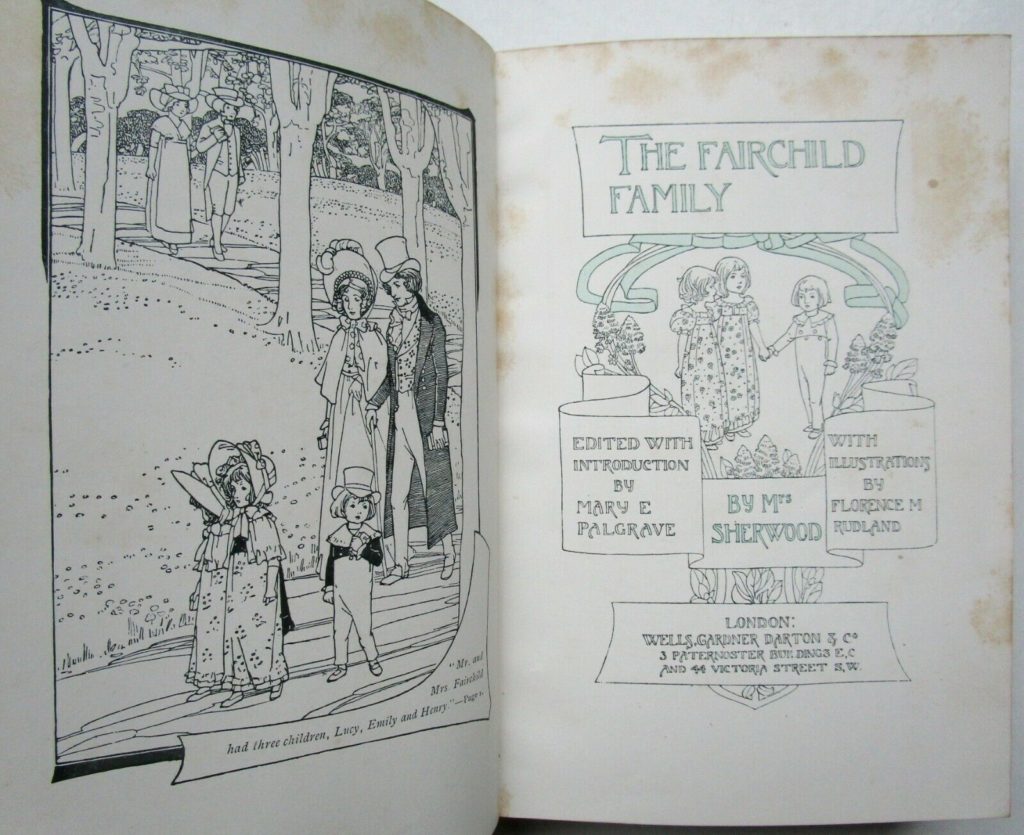

1897: Florence M. Rudland and another Lawrence-Bullen edition

Lawrence and Bullen used the same translation again (still by Sir Edmund Gosse) and in 1897 they reissued the work with different illustrations by Florence M. Rudland, a disciple of Arthur J. Gaskin at the Birmingham School of Art, who brings us back with her more decorative and floral touch. Among other works illustrated by Rudland, we find The History of the Fairchild Family by Mary Martha Sherwood (you can see an edition here) and some Hans C. Andersen’s fairy-tales. I was unfortunately unable to find any picture of her work on Undine.

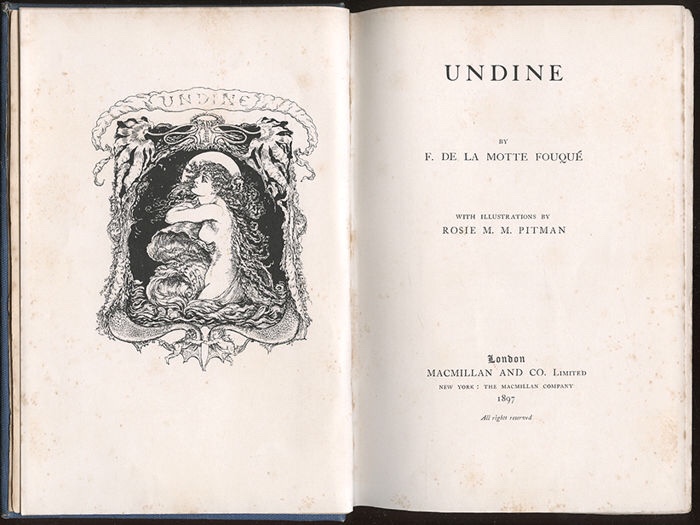

1897: Rosie M.M. Pitman and the Macmillan edition

Another edition and translation was published in 1897, by Macmillan and Co. Ltd., and it’s a grand one at that: it has more than sixty illustrations by Rosie M.M. Pitman, an English illustrations who has in this her masterpiece: her work is in the art nouveau style, sinuous and decorative, with no restrain for nudity and eroticism. Only eight years later, she would marry a German guy and give up her career. Some of her illustrations can be found here. Some scans of the book are here.

1907: Katharine Cameron and the Jack edition

Katharine Cameron was a member of the Glasgow Society of Lady Artists and she worked on lots of books and fairy-tales mostly retold and rewritten for children. In 1907, she illustrated one Undine, Told to the Children by Mary Macgregor for the London editor T.C. & E.C. Jack. The same Mary Macgregor also did some Stories of Siegfried and Stories of King Arthur. Her work is in delicate watercolours and Undine is portrayed as a child. I have zero idea how that works out with the whole marriage thing and I’m frankly afraid to find out, so do not ask.

The work is available on Project Gutenberg, but of course Project Gutenberg has been blocked in the Country I’m writing from, and there’s a very limited amount of material you can find on-line so, in case you own or you can get your hands on a copy, be a darling and share. She died in 1965, though, so the work is technically not in the public domain yet.

1908: E.F. Skinner and the Nelson edition

Following the stream of retellings and adaptations of the tale in order to make it appealing (and suitable) for children, in 1908 Nelson published The Story of Undine and House Island, with seven colour plates by Edward Frederick Skinner, a painter mostly famous for his urban and factory scenes (you can see some of his works here). There’s a copy of the book on auction here, with some good pictures.

1909: Brinsley Le Fanu and the Stead edition

W.T. Stead, a pioneer English newspaper editor, was the publisher of a highly popular pink paperback series called Books for the Bairns, which included fairy tales just as much as classical literature. There’s a shitload of them and a complete list is available here. They were small and nice booklets, mostly illustrated by Brinsley Le Fanu with line drawings and The Story of Undine. The Sprite Maiden, published in 1909 as nr. 163 of the series, makes no exception.

Brinsley Le Fanu, born George Brinsley Sheridan Le Fanu, was one of the children of the novelist Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, the leading ghost story writer who gave us gothic tales such as Carmilla. Throughout his career, Brinsey illustrated lots of his father’s works (his illustrations for The Watcher and Other Weird Stories are amazing and you can see the cover here) and some of the most beloved Edwardian works including Edmund Spenser‘s Faerie Queene, and a one volume edition of both Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, published by Benn around 1907. I’m sure you know his Alice work, at least the one in the Books for the Bairns series. I was unfortunately unable to find any picture of issue 163.

1930: Allen Lewis and the Limited Editions Club

This particular edition was not listed in many of the pages I found, but I stumbled into a couple of auctions mentioning it on one of my favourite resources, the Heritage Auctions website. It was a limited edition of 1500 numbered copies, signed by the author, and for what I can see, the illustrations are gorgeous. You can find a biography of the artist on the Annex Gallery website: he was apparently friend to illustrator Ernest Haskell, and protected by Hamilton Easter Field who set up his studio in a warehouse he owned. His first commission for a book was in 1915, for Charles S. Brooks’s Journeys to Bagdad.

Inspired Works: paintings

Aside from the illustrated editions, Undine inspired lots of art, especially in the Romantic, pre-Raphaelite and Edwardian periods. My favourites have to be Henry Fuseli and J.W. Waterhouse.

1802: Johann Heinrich Füssli

One of my favourite romantic artists from when I was a youngster, Henry Fuseli worked around the subject of Undine on several occasions, producing both oil paintings and sketches. Later works include this painting from 1821, but my favourites have to be this watercolour from 1802 and this watercolour from 1822. Oddly enough, the latter is preserved at the Auckland Art Gallery and you can find more information on their website. It’s not the only work they have from Fuseli: you can see all of them here.

1830: Theodor von Holst

Theodor von Holst was a British literary painter who produced works both inspired by classics (Virgil, Dante, William Shakespeare), and by contemporary fiction: he was the first artist to illustrate Mary Shelley‘s novel Frankenstein in 1831, and he was fascinated by German romantics such as Goethe and Hoffmann. Being amongst them, of course Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué was no exception. I would lie if I said I like his works, with the notable exception of The Wish (1840), and a Fantasy Based on Goethe’s ‘Faust’ from 1834. When he tried to paint normal beings, the result can be rather ghastly (see this one).

1843: Daniel Maclise

Daniel Maclise was an Irish painter and illustrator, member of the Royal Academy, who worked a lot around the subjects of chivalry and courtly life. Famous are his Chivalric Vow of the Ladies, and his Spirit of Chivalry, but he also did historical subjects such as The Meeting of Wellington and Blücher after the Battle of Waterloo, a monumental painting commissioned to him on 1858 for the walls of Westminster Palace. The other one was The Death of Nelson, completed in 1864. According to Charles Dickens, who was a close friend of Maclise, the artist was noticed by Queen Victoria, who requested him to paint some “secret pictures” as a surprise to Prince Albert for his birthday. The prince was evidently impressed by what he saw, because he became his patron too and commissioned him a fresco with a scene from John Milton’s Comus (we keep meeting this tale), on the walls of the Garden Pavilion at Buckingham Palace. The work we’re concerned about, however, is not a fresco (a technique Maclise grew uncomfortable with), but an oil on panel from 1843. You can see it on the website of the Royal Collection Trust.

In this scene, … the young knight Huldbrand escorts his bride, Undine, through an enchanted forest full of writhing elves and goblins. By her marriage to a human the water spirit Undine gained a mortal soul but lost the prospect of eternal life. Father Heilmann, having just performed the ceremony, emerges from beneath a canopy of trees, while the evil and sinister Kühleborn, spirit of the waters and Undine’s uncle, rises up ahead of them in an attempt to return Undine to her family.

Daniel Maclise, “A Scene from Undine” (Inscribed 1843). Oil on panel | 44.5 x 61.0 cm | The Royal Collection Trust

The painting was turned into a print by Charles William Sharpe and you can see one copy at the British Museum.

1846: William Turner

The famed revolutionary painter Joseph Mallord William Turner worked around the topic of Undine around 1846, when he exhibited his “Undine Giving the Ring to Massaniello, Fisherman of Naples” as a companion picture to “The Angel standing in the Sun”. He was approaching the end of his life and, though he died of cholera, his later years were marked by an increased eccentricity and a strong depression following the death of his beloved father. This somehow reflected in his works, which became even more vibrant and visionary than some of his most impressive earlier paintings. The scene from Undine is amongst them and you can see it at the Tate Gallery. Its twin picture can be seen on this page.

“Undine Giving the Ring to Massaniello, Fisherman of Naples” by Joseph Mallord William Turner (1846)

1859: Francis John Wyburd

Francis John Wyburd was a British artist who studied at Lille, in France, and was educated as a pupil of Thomas Fairland, a renowned engraver and lithographer. You have a rich biography with several examples on this page. His work on Undine was inspired by a visit in Scotland, and particularly to the caves around the Isle of Arran, such as the suggestive King’s Cave.

On October 1859, one of his works featured on the Illustrated London News and the website of the British Museum offers us a scan of the page in question. The painting had been on display at the Royal Academy of Arts the same year. It was later turned into an etching and you can find several reproductions of this work around the web.

I shall read my doom in your eyes, even before your lips pronounce it…You, my dear husband, now actually behold an Undine before you.

1865: Henry Peters Gray

Henry Peters Gray was an American genre painter, pupil of Daniel Huntington and another one of those guys who studied in Florence and Rome. His most famous work, The Greek Lovers, currently at the MET, was painted after his trip to Italy, but he also painted scenes coming from literature, such as Washington Irving‘s The Pride of the Village, also at the MET. His Undine, is at the Smithsonian and you can see it on their website.

1872: J.W. Waterhouse

If there’s such a thing as a crime for loving a painter too much, I would plead guilty for the work of John William Waterhouse. He did an Undine in 1872, particularly the revelation scene where our maiden shows her true nature to her knight. The painting is in a private collection (can you believe it? someone actually owns it).

Inspired Works: Sculpture

1859: Charles Francis Fuller

Similarly to Daniel Maclise, Charles Francis Fuller was an artist who worked a lot with the British Government, for instance doing the Monument to the Maratha Maharajah of Kohlapur, Rajaram Chhatrapati in Florence, as a homage to the young Marjah who died on his return voyage after seeing Queen Victoria. Fuller had been living in Florence since 1853, after resigning from the British army, and he was studying with the American Hiram Powers. In 1859, Queen Victoria asked him to create this bust of Undine, again as a present for Prince Albert’s birthday, and again the work is preserved at the Royal Collection Trust. The front is amazing, with the delicate expression and flowing hair, but the details at the back are even better.

1870: William Calder Marshall

William Calder Marshall was a Scottish sculpture mostly famous for his monument to Edward Jenner, the scientist who discovered the concept behind vaccinations, originally set up in Trafalgar Square with a 1858 inauguration ceremony presided over by Prince Albert, and moved to Kensington Gardens in 1862, where you can currently see it. He’s also the author of the allegorical Agriculture in the Albert Memorial and remains to these days one of the most prolific and successful sculptors of the Victorian Era.

His Undine is on display at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool and depicts our heroine half-melted with the waters that define her. There’s a horrible picture on Wikimedia, from a guy who even asks to be credited. Luckily enough, there are also some good materials provided by the people of Scan The World at MyMiniFactory, including the stl model.

The beautiful scan and rendition of William Calder Marshall‘s Undine, provided by MyMiniFactory.

1880: Chauncey Bradley Ives

Chauncey Bradley Ives was a neoclassical American sculptor who worked a lot around mythological subjects such as Pandora, Ariadne and, of course, Undine. His sculpture of her rising from the waters is preserved at the Smithsonian Institute and you can see it here.

Inspired Works: Arts and Crafts

1941: Ruth Raemisch

At the Metropolitan Museum, you can find this beautiful box illustrated with scenes from Undine. Ruth Raemisch was an American artist born in Germany and there are some of her paintings on auction around the web, but I could not dig up any other information on her nor on the occasion she did this work around Undine.

1 Comment

Pingback:Shut Up and Drink Me – Shelidon

Posted at 00:01h, 02 May[…] most famous historical Alice reaching out, is probably Brinsley Lefanu‘s, a guy I’ve already talked about in correlation with Undine. He was the main illustrator for W.T. Stead‘s paperback collection […]