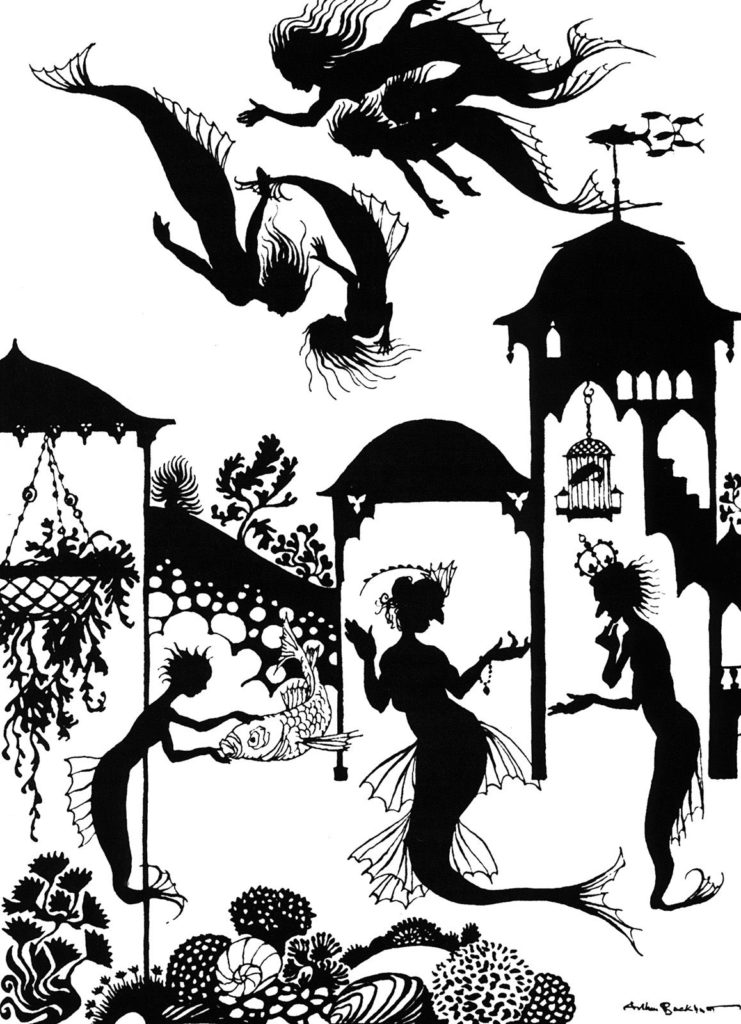

When I talked about Arthur Rackham, quite some weeks ago it seems, I mentioned that two themes might have been worthy of a separate discussion: his love for twisty trees and his portrayal of water-nymphs, mermaids, water-maidens such as Woglinde, Wellgunde, and Floßhilde and my personal favourite: Undine. So this Sunday I step out of The Ingoldsby Legends and try to step in this rather watery pool of subjects, always using Rackham as a navigator. Let’s start with the most famous of them all: The Little Mermaid.

Frontispiece by Dugald Stewart Walker (1914)

The Little Mermaid

The Little Mermaid is probably one of the saddest and most infuriating fairy-tales ever written. It appeared – on April, 7th 1837 – in the very first collection of Fairy Tales Told for Children by Hans Christian Andersen, then again on December, 18th 1849 as a part of his Fairy Tales 1850 and again on December, 15th 1862 in the first volume of Fairy Tales and Stories. In theory, a complete publication history can be found here (but the website stopped working properly few months ago). It features both in The Annotated Hans Christian Andersen and The Annotated Classic Fairy-Tales curated by Maria Tatar for the W.W. Norton & Co editions, one of the most precious resources when it comes to annotated fairy-tales, and on-line you can refer to the wonderful website surlalunefairytales.com.  The tale is generally described as follow: a young mermaid who lives under the sea, dreams to live in the world above and eventually rescues a prince from drowning. She falls in love and she strikes a bargain with a Sea witch who grants her legs and, in turn, asks for her voice: she’ll be able to stay human if she manages to make the prince fall in love with her.

The tale is generally described as follow: a young mermaid who lives under the sea, dreams to live in the world above and eventually rescues a prince from drowning. She falls in love and she strikes a bargain with a Sea witch who grants her legs and, in turn, asks for her voice: she’ll be able to stay human if she manages to make the prince fall in love with her.

«Unless a man were to love you so much that you were more to him than his father or mother; and if all his thoughts and all his love were fixed upon you…»

There’s a lot of things to unpack here: the fact that only a man can save her (and she can’t, let’s say, be adopted into the human world, and folklore would probably have respected that), and the fact that she has to find a man able to love her more than his mother which, as we all know, borderlines on the impossible. The ending varies whether you stick to the fairy-tale or you go with more cartoonish versions: in the original tale, she fails miserably and goes back to nature. The most problematic part of the literary tale, however, doesn’t strictly have to do with the ending and has more to do with the reason for this ending, being that the mermaid has no soul. The root of this tale is Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué‘s Undine, one of the other tales with water maidens illustrated by Rackham, as Andersen himself explains in a letter to a friend:

I have not, like de la Motte Fouqué in Undine, allowed the mermaid’s acquiring of an immortal soul to depend upon an alien creature, upon the love of a human being. I’m sure that’s wrong! It would depend rather much on chance, wouldn’t it? I won’t accept that sort of thing in this world. I have permitted my mermaid to follow a more natural, more divine path. (H.C. Andersen in a letter from 1837)

The fact that one guy would think to put the expressions “more natural” and “more divine” in the same sentence actually says a lot about the guy.

Hans Christian Andersen in a 1869 photograph. As you might have guessed by now, I’m not particularly fond of the guy.

About 50 years after, Oscar Wilde published his The Fisherman and His Soul, where a fisherman falls in love with a mermaid (instead of being the other way around) and seeks for a way to give up his soul (instead of her trying to gain one) so she will accept him as a lover. It’s probably the biggest “fuck you Andersen” tale in human history. The tale was included in the collection A House of Pomegranates, published in 1891 as a second collection for The Happy Prince and Other Tales (1888). It was beautifully illustrated by Jessie Marion King, one of the Glasgow Girls, and each of the four stories was dedicated to a public figure: “The Fisherman and His Soul” was dedicated to Alice Heine, Princess of Monaco.

Jessie M. King illustration of the witch in “The Fisherman and His Soul”

The original working title for the story as Andersen set up to write it was “Daughters of the Air” because, spoiler alert, the Prince is unable to love her and, eventually the mermaid is united with other spirits longing for immortal souls (all female too), and it turns out that the way to achieve this goal is going through three hundred years of good deeds. That is unless children behave naughtily, says Andersen, because every day they see a naughty child the daughters of the air have one more day added to their «time of trial».

Arthur Rackham’s illustration to the final scene of “The Little Mermaid”, where she joins the daughters of the air in mermaid’s purgatory.

P.L. Travers, the stiff and untameable author of Mary Poppins, also had something to say about Andersen’s blatant morality, considering it an attempt of blackmailing the children into good behaviour and warning Andersen that the children are not falling for it: they’re simply indulging an old man.

The story descends into the Victorian moral tales written for children to scare them into good behaviour… Andersen, this is blackmail. And the children know it and say nothing. There’s magnanimity for you.

There’s also a long line of critics who added their voices in pointing out how really bad the moral aspects of this fairy-tale are, such as Marina Warner in her Once Upon a Time: A Short History of Fairy-Tales (2014). You can also find someone who’s in favour of this ending, however: read for instance this article by Allie Dawson.

Marina Werner’s book. If you think the cover art looks familiar, it’s because it looks a lot like Justin Rowe‘s work I showed you during my 2020 advent calendar.

Aside from the moral aspects of the story and the most disturbing details, the story is also beautifully written and has a marvellous use of colours and sceneries, so it’s worth a shot at least to take a look at three aspects: its characters, its places and, as I was saying, the use of colours.

1. Characters

1.1. The Little Mermaid

Andersen is described as the youngest daughter of the widower Sea King, and this (as we know by now) is a trope in folklore: she’s the youngest princess, the youngest sibling, and as such we tell her story. Traditional folklore and fairy-tales are usually concerned with only children or youngest siblings: the unhealthy obsession with first-borns in modern fantasy is rather unnatural and speaks a lot about a shift in focus we should really be concerned about. She’s nine years old, and she’s described as the prettiest among the King’s beautiful daughters:

…her skin was as clear and delicate as a rose-leaf, and her eyes as blue as the deepest sea; but, like all the others, she had no feet, and her body ended in a fish’s tail.

Though mermaids are not always portrayed with fish features, Andersen chooses not to go with full human features and her tail, as we know, is a central symbolic element in Andersen’s tale.

The character of the Little Mermaid was highly autobiographical and rivers of ink have been spilled on this topic: Andersen longed to social climb and the character’s longing for a “world above” was explicitly resounding with him. Her depiction as «a strange child, quiet and thoughtful» has sometimes been considered autobiographical too, on Andersen’s behalf, and her companions can be compared to the writer’s characters and creations, good company for an introverted soul who was longing for other worlds. The mermaid, a creature who’s longing for a transformation to gain access to another world, has also been perceived as a character talking to the queer community: the topic is explicitly explored in the wonderful documentary Howard, exploring the life of Disney songwriter Howard Ashman who died of AIDS in March 1991, at the age of 40. With time, the same topics have spoken to the heart of the whole queer and particularly the transgender community (try and read here, for instance). There are several interesting details, within the tale, that suggest the mermaid actually crosses genders, when she becomes a human: in the actual story, if you bother to reads it, the Prince treats her more like a page (if not a pet), she dresses in a page attire and rides the horse with him. This, in addition to the fact that he eventually wanders off marrying an “actual woman”, speaks volumes as to a general pain that doesn’t make me like Andersen anymore (if anything, it infuriates me furtherly because instead of breaking free the guy is trying to cage children), but certainly adds layers and layers of depth to the story. As far as I know, also due to a mis-translation of the term Andersen uses for the page attire the mermaid is given, no illustrator ever caught or followed up on that. Which is rather a shame.

Another illustration by Edmund Dulac, with the meeting between the transfigured mermaid and the prince.

1.2. The Mer-King

A widower who never remarried, he has a more than marginal role in the original story. We see his palace, sure, but the children are tended to by his mother. He’s seen only once, when the mermaid is already on land, after she gets the visit of her sorrowful sisters: she sees him from a distance, stretching his arms towards her, but he never ventures close to the shore and the fact that this encounter is described in conjunction with a similar encounter with the grandmother makes it loose a lot of its grip. It’s a futile king, as we see a lot in both fairy-tales and real life. According to SurLaLune, the best known Sea King in European folklore is from Russia and recommends a book by Aaron Shepard. called The Sea King’s Daughter: A Russian Legend. with illustrations by Gennady Spirin.

1.3. The Royal Grandma

The king’s household description is not the one we expect from a king: since he is a widower, «his aged mother keeps house for him». This grandmother is «exceedingly proud of her high birth»: she wears twelve oysters on her tail as a status symbol, while the highest ranking merfolk in the kingdom are usually allowed to wear a maximum of six. It’s unclear whether there is an oyster police going around stripping oysters from the tails of pretenders. She is not depicted as a negative character, however. On the contrary, she’s praise-worthy, especially for the way she cared for her grand-daughters. She’s portrayed as a story-teller, indulging her youngest grand-daughter with tales of the world above and of things like «the ships and of the towns, the people and the animals».

Her grandmother called the little birds fishes, or she would not have understood her; for she had never seen birds.

One has to wonder how could the grandmother know, and it turns out it’s a coming-of-age thing.

“When you have reached your fifteenth year,” said the grand-mother, “you will have permission to rise up out of the sea, to sit on the rocks in the moonlight, while the great ships are sailing by; and then you will see both forests and towns.”

She’s also the one to dress up the youngest princess when she comes of age: she places a wreath of white lilies made of pearls on her head and orders «eight great oysters to attach themselves to the tail of the princess to show her high rank», dismissing the grand-daughter complain that they hurt because, as we all know, «pride must suffer pain».

An original sketch by Arthur Rackham into one of 9 limited edition copies (you can read all about it here): though the fish a birdcage never actually appears in the tale, grandma talks about birds as if they were fishes, for her grand-daughter to understand, so a few illustrators picked up on that.

The Royal Grandma is also central in explaining that merfolk live much longer than humans and that, in return, merfolk do not have souls.

“If human beings are not drowned,” asked the little mermaid, “can they live forever? do they never die as we do here in the sea?” “Yes,” replied the old lady, “they must also die, and their term of life is even shorter than ours. We sometimes live to three hundred years, but when we cease to exist here we only become the foam on the surface of the water, and we have not even a grave down here of those we love”.

“We have not immortal souls, we shall never live again; but, like the green sea-weed, when once it has been cut off, we can never flourish more. Human beings, on the contrary, have a soul which lives forever, lives after the body has been turned to dust. It rises up through the clear, pure air beyond the glittering stars. As we rise out of the water, and behold all the land of the earth, so do they rise to unknown and glorious regions which we shall never see.”

Cheers!

A beautiful illustration of our gloomy mermaid by Nadezha Illarionova: she did beautiful work and I put a lot of her drawings in the section about the other sisters.

Giving that the news is not the cheeriest of them all, and that our little mermaid is rather mournful about the fact that she’ll never know «the happiness of that glorious world above the stars», grandma tries first to convince her that merfolk are «much happier and much better off than human beings» and eventually does what everyone do when someone’s feeling down.

“Let us be happy,” said the old lady, “and dart and spring about during the three hundred years that we have to live, which is really quite long enough; after that we can rest ourselves all the better. This evening we are going to have a court ball.”

The ball will eventually provide the distraction needed for the mermaid to sneak out and go to visit the Sea Witch.

1.4. The (other) Princesses

Our little mermaid is the youngest of six sisters, and though by the end of the tale she’s fifteen (so they must be older), they are seem to be depicted as children: playing in the hallways and in the garden, arranging their flowers, collecting with delight «the wonderful things which they obtained from the wrecks of vessels».

When the eldest princess turns fifteen, she is allowed to surface and, according to her, the most beautiful thing you can do is «to lie in the moonlight, on a sandbank, in the quiet sea, near the coast, and to gaze on a large city nearby, where the lights were twinkling like hundreds of stars; to listen to the sounds of the music, the noise of carriages, and the voices of human beings, and then to hear the merry bells peal out from the church steeples». The eldest sister is clearly a musical type, as her tale is mostly made of sounds.

One of Arthur Rackham’s inkworks for the Little Mermaid, unfortunately unavailable at a higher resolution because someone tried to make money with it.

A year passes in the tale, and then the second sister turns fifteen, so she’s allowed to go up as well. The tales she brings back are mostly visual: she goes up during the sunset and, according to her, this is the most beautiful sight ever.

The whole sky looked like gold, while violet and rose-colored clouds, which she could not describe, floated over her; and, still more rapidly than the clouds, flew a large flock of wild swans towards the setting sun, looking like a long white veil across the sea.

The second sister even tries to swim towards the sun, but she’s unable to reach it before it sinks into the waves and «the rosy tints» of the sunset fade from both the clouds and the sea.

Another inkwork by Arthur Rackham captures beautifully the “family life” at the Sea King’s palace: you can see all the sisters (with one little intruder) and the Royal Grandma too.

The third princess turns fifteen the year afterwards and she’s the boldest of all: she swims up through a river, in plain daylight, and sees the inland: she’s fascinated by the «green hills covered with beautiful vines; palaces and castles peeped out from amid the proud trees of the forest», but her tale is the richest of all, mixing both sounds and colors: she hears birds singing, she feels the burning of sunlight on her face, so much that she has to dive to cool her skin, and even encounters a flock of human children playing in the water, but she’s unable to play with them because both them and her are scared off by what the narrator knows to be a black dog.

But she said she should never forget the beautiful forest, the green hills, and the pretty little children who could swim in the water, although they had not fish’s tails.

The fourth one is more prudent and shy, especially after her sister’s tale from the year before, so she stays in the open water and enjoys the quiet open see, the sky above her looking «like a bell of glass». She also sees some ships, from a distance, looking like sea-gulls, and dolphins messing around, and great whales spouting water like «a hundred fountains».

A beautiful illustration by Nadezha Illarionova you can read an interview and see some more works here).

The fifth princess, at last, turns fifteen in winter and has the chance to see different colors, to enjoy a different sight: the sea is green, large icebergs are floating about like pearls on the water or, in an odd term of comparison for a mermaid, «larger and loftier than the churches built by men». Their shapes enchant her and she compares them to diamonds.

She had seated herself upon one of the largest, and let the wind play with her long hair, and she remarked that all the ships sailed by rapidly, and steered as far away as they could from the iceberg, as if they were afraid of it. Towards evening, as the sun went down, dark clouds covered the sky, the thunder rolled and the lightning flashed, and the red light glowed on the icebergs as they rocked and tossed on the heaving sea. On all the ships the sails were reefed with fear and trembling, while she sat calmly on the floating iceberg, watching the blue lightning, as it darted its forked flashes into the sea.

It is as if all the five sisters are able to bond on that experience and, as they get old enough to swim about where they want, they often dismiss the world above and say that home is better, but still they go up and sing sailors to their deaths with voices more beautiful than any mortal, like good little mermaids.

…and before the approach of a storm, and when they expected a ship would be lost, they swam before the vessel, and sang sweetly of the delights to be found in the depths of the sea, and begging the sailors not to fear if they sank to the bottom. But the sailors could not understand the song, they took it for the howling of the storm. And these things were never to be beautiful for them; for if the ship sank, the men were drowned, and their dead bodies alone reached the palace of the Sea King.

(ok, to be completely honest it’s more like they know they’re going to die and they try to ease their passing, but still it’s fucking creepy)

The sisters do not play a central role in our mermaid’s tale, but for sure they’re less marginal than the king. They inquire as to what has been the first adventure of our mermaid when she surfaced, but since she has rescued the prince from drowning she doesn’t want to share.

Her sisters asked her what she had seen during her first visit to the surface of the water; but she would tell them nothing.

Eventually she tells one of them and of course they’re unable to keep the secret but this turns out to be a good thing, as a couple of friends to one of the sisters are able to tell our mermaid where the Prince lives. After the mermaid transitions to a human and gets on land, we see the sisters a couple of times more, each time when they surface and they sing to her their sorrows for having lost her.

Once during the night her sisters came up arm-in-arm, singing sorrowfully, as they floated on the water. She beckoned to them, and then they recognized her, and told her how she had grieved them. After that, they came to the same place every night.

The scene illustrated by Boris Diodorov, who decides to condensate the encounters of different nights in one single scene.

The second time, they surface when she’s sailing with the prince on his ship. Every scene is rather melancholic: though our mermaid tries to convince her sisters (and us) that she’s rather happy, she really is not, as the Prince never demonstrates the slightest romantic interest in her, and nothing even remotely similar to physical attraction.

In the moonlight, when all on board were asleep, excepting the man at the helm, who was steering, she sat on the deck, gazing down through the clear water. She thought she could distinguish her father’s castle, and upon it her aged grandmother, with the silver crown on her head, looking through the rushing tide at the keel of the vessel. Then her sisters came up on the waves, and gazed at her mournfully, wringing their white hands. She beckoned to them, and smiled, and wanted to tell them how happy and well off she was…

There’s a third very important encounter, in which the sisters show up on our little mermaid’s last night, after she has failed to marry the prince and in fact her prince have married another: they rise from the sea and the mermaid sees that they have no hair anymore. They explain that they have given their beautiful hair to the sea witch so that their sister will not have to die that night, and they give her a knife. If she kills the prince with that knife, she’ll be a mermaid again.

1.5. The Sea Witch

The Sea Witch gets mentioned the first time when the grandmother organizes the court ball, as our mermaid forms the resolution of not wanting to settle for having no soul (and we know that when highly moralistic people write stuff, it’s always bad when someone tries to better his/her condition). The mermaid has always been afraid of the witch, but she does seem to be her only hope. The witch lives even deeper in the sea, after a stretch of what is defined «mire», literally a swamp or a bog. She calls this underwater bog her «turfmoor» and her house is to be found across this swamp and in the middle of a forest Walt Disney’s original crew from Snow White would have had a field day recreating and animating.

in the centre of a strange forest, in which all the trees and flowers were polypi, half animals and half plants; they looked like serpents with a hundred heads growing out of the ground. The branches were long slimy arms, with fingers like flexible worms, moving limb after limb from the root to the top. All that could be reached in the sea they seized upon, and held fast, so that it never escaped from their clutches.

American illustrator Charles Santore did a beautiful work in trying to convey at least the sense of horror and peril in the witch’s realm.

The white skeletons of human beings who had perished at sea, and had sunk down into the deep waters, skeletons of land animals, oars, rudders, and chests of ships were lying tightly grasped by their clinging arms; even a little mermaid, whom they had caught and strangled; and this seemed the most shocking of all to the little princess.

One of Nadezha Illarionova‘s most incredible illustrations: the mermaid making a deal with the Sea Witch.

Beyond that forest, the witch lives in a home «built with the bones of shipwrecked human beings» and human bones, much like the Baba Yaga of Russian folklore. She’s not physically described, but illustrators often drew for her appearances from the animals she’s described as accompanying herself with: she’s surrounded by «fat water-snakes» which she’s calling «her little chickens» and whom she allows to «crawl all over her bosom» and she has a toad for a pet, whose she allows «to eat from her mouth, just as people sometimes feed a canary with a piece of sugar». Which is frankly rather disgusting to everybody.

The Sea Witch as illustrated by Ivan Bilibin: there’s a striking resemblance between she and her pet toad (as it often happens with pets).

In the fairy-tale, the witch is not the evil character we are used to think about: she explains, honestly and openly, what are the difficulties the mermaid will encounter in her attempt to gain a mortal soul and she even states that she thinks the endeavour is silly and will cause her only sorrow. She talks to her about the pain she will feel in transforming and every step she takes, she warns her that from the moment she becomes human she’ll never be a mermaid again, she tells her that the moment the prince marries another her heart will break and she will become foam in the sea. The potion she promises, requires the witch’s own blood, so the fact that she’s asking for payment even seems reasonable enough.

“You have the sweetest voice of any who dwell here in the depths of the sea… this voice you must give to me; the best thing you possess will I have for the price of my draught. My own blood must be mixed with it…” “But if you take away my voice,” said the little mermaid, “what is left for me?” “Your beautiful form, your graceful walk, and your expressive eyes; surely with these you can enchain a man’s heart. Well, have you lost your courage? Put out your little tongue that I may cut it off as my payment…”

The scene of the potion-making has all the grandeur you might be expecting: the witch places her cauldron on the fire – though no one seems to object neither to wonder how could she have made a fire underwater and our little princess doesn’t blink at seeing that some of the things above can apparently also be found below – and pricks her breast for a «black blood drop».

The steam that rose formed itself into such horrible shapes that no one could look at them without fear. Every moment the witch threw something else into the vessel, and when it began to boil, the sound was like the weeping of a crocodile.

The witch then literally cuts off the mermaid’s tongue, for the joy of all children everywhere.

1.6. The Sun and Stars

The sun, often associated with the colour red as we’ll see, can be considered a proper character, as it’s pivotal in its movement. It talks both about the earth and the heavens, two worlds the mermaid is longing for.

In calm weather the sun could be seen, looking like a purple flower, with the light streaming from the calyx.

She’s not the only one to have a certain fascination for this, as we have seen: the second sister even tried to swim towards the sunset, but couldn’t catch it before it sank into the water, and the third sister swam in plain daylight, feeling on her face the burning of the sunrays themselves. However, none of them feel the same pull of our princess, none of them are troubled by having no soul and none of them have saved a human (on the contrary, they have eased the passing of quite a few). The perfect symbol of both our mermaid’s fascinations (the heavenly afterlife and the human world) is the fireworks she can see when she surfaces next to the prince’s ship.

Great suns spurted fire about, splendid fireflies flew into the blue air, and everything was reflected in the clear, calm sea beneath.

Crystal Galloway did an Indian version of The Little Mermaid: you can see all of them in this blog post.

1.7. The statues

Another unconventional character is the marble statue the mermaid is keeping and spending much time with.

It was the representation of a handsome boy, carved out of pure white stone, which had fallen to the bottom of the sea from a wreck. She planted by the statue a rose-colored weeping willow. It grew splendidly, and very soon hung its fresh branches over the statue, almost down to the blue sands. The shadow had a violet tint, and waved to and fro’ like the branches; it seemed as if the crown of the tree and the root were at play, and trying to kiss each other.

1.8. The Prince and Princess

The last character within the tale is the prince our mermaid falls in love with. He’s a little more than useless, as it often happens in fairy-tales, and even if he doesn’t reach the peaks of the king in certain Sleeping Beauty tales, he still is quite a piece of work. For starters, he founds this naked mute girl on the beach and basically takes her as his pet: he has her childishly dressed «in costly robes of silk and muslin» (in contrast to the female slaves who are dressed in a more sensual silk and gold), he calls her «his little foundling» and he decrees «she should remain with him always»: she’s granted gracious permission «to sleep at his door, on a velvet cushion». She’s then dressed in a page outfit and accompanies him everywhere.

Illustration by A. Duncan Carse.

However, I guess things could be worst, considering how princes usually behave in fairy-tales: he has affection for her «as he would love a little child, but it never came into his head to make her his wife», he expresses his affection by kissing her on the forehead and never anything else, and he speaks of her as a good-luck charm which was sent to him to remind him of another fair maiden who had saved him from drowning. Also when other women are around, there’s never any doubt she’s not in competition with them if not in her mind.

Beautiful female slaves, dressed in silk and gold, stepped forward and sang before the prince and his royal parents: one sang better than all the others, and the prince clapped his hands and smiled at her. This was great sorrow to the little mermaid; she knew how much more sweetly she herself could sing once…

Illustration by A. Duncan Carse.

So far so good, I guess. Things go south of course when the Prince is to meet his soon-to-be bride, «the beautiful daughter of a neighboring king». It’s an arranged marriage, and our useless prince is not too happy about it.

“I must see this beautiful princess; my parents desire it; but they will not oblige me to bring her home as my bride. I cannot love her; she is not like the beautiful maiden in the temple, whom you resemble. If I were forced to choose a bride, I would rather choose you, my dumb foundling, with those expressive eyes.” And then he kissed her rosy mouth, played with her long waving hair, and laid his head on her heart, while she dreamed of human happiness and an immortal soul.

I think we can all agree that saying “I would rather choose you” is bad enough, but saying that you would rather choose a girl because she’s dumb… well, I don’t know why I’m even surprised at this, at this point in my life. What’s infuriating, here, is the level of idiocy with which Andersen completely ignores the way the prince is treating a girl just because the narrator knows she has no soul. He’s sort of implying that the prince has an instinctive knowledge of this fact and acts accordingly. While, in fact, we know he’s just a bastard playing with a mute fifteen-years-old girl in a children’s story. I might be about to throw up and I guess the sisters were right: you should drown the bastard at the first chance you get.

As it happens, the princess is indeed beautiful and the prince is instantly convinced it was her who he saved him from the storm. She «was being brought up and educated in a religious house, where she was learning every royal virtue», so she doesn’t contradict him which I bet will make for a very happy marriage, considering that the prince was already starting to consider ideal the company of a devoted woman who did not speak.

Then the little mermaid… was obliged to acknowledge that she had never seen a more perfect vision of beauty. Her skin was delicately fair, and beneath her long dark eye-lashes her laughing blue eyes shone with truth and purity.

Since you have to swallow everything if you want to be celebrated as the heroine of a fairy-tale, especially when it’s written by a man such as Andersen, our little mermaid doesn’t take him and drown him on the spot, but she kisses his hand in agreement of his statement how how she should feel.

“You will rejoice at my happiness; for your devotion to me is great and sincere”.

2. Colours

The colours of the story are a striking part of the narrative: the wonderful website called SurLaLune has a good set of annotations you can read here and some of them are focusing on the colours of the tale:

Blue is the dominant color of this story, thanks in part to its watery setting. Blue represents the little mermaid’s underwater world all the way to the color of her eyes and the sand. Notice how often the color is used to describe an element of the little mermaid’s world as you read the story.

The story starts with a description of this deep blue sea, which is compared to the most beautiful cornflower (or bachelor’s button, a blue-violet flower also used for pigmentation and the very essence of Prussian’s blue, for the tale according to which Queen Louise of Prussia was fleeing Napoleon and hid her children in a field of cornflowers, where she weaved them garlands of those flowers in order for them not to make a word while the soldiers were passing by).

Over everything lay a peculiar blue radiance, as if it were surrounded by the air from above, through which the blue sky shone, instead of the dark depths of the sea.

The term “blue” appears 16 times in the original tale, almost always related to the water, the light underwater or elements associated with it, such as the sand near the King’s castle or the flowers in the sisters’ gardens. Our little mermaid’s eyes are also blue, just like the ones of the princess who will eventually pass for her and marry that asshole of a prince.

Laura Barrett did some beautiful black and blue illustrations to a retelling of the Little Mermaid and you can read about it (and her creative process) here.

The other predominant colour is red, which comes to symbolize the two worlds above the water: the dry land and the heavens.

In calm weather the sun could be seen, looking like a purple flower, with the light streaming from the calyx.

Our mermaid’s longing for everything the sun represents is immediately symbolized by the way she plays in the garden: while her sisters are arranging their flowers in the forms of whales and mermaids, our little mermaid has a round garden, like the sun, with only the reddest flowers, like the rays of the sunset. After blue, it’s the colour that recurs the most, with 11 mentions, mostly related to the sun or the sky at sunset, crimson recurring a couple of times (most notably in the curtains of the prince’s wedding bed) and purple with three mentions (again one for the tent in the centre of the wedding ship). There’s also a nice scene in which the mermaid holds a knife and is thinking to use it on the prince and his bride, during her last night, but eventually tosses it into the water.

The little mermaid drew back the crimson curtain of the tent, and beheld the fair bride with her head resting on the prince’s breast. She bent down and kissed his fair brow, then looked at the sky on which the rosy dawn grew brighter and brighter; then she glanced at the sharp knife, and again fixed her eyes on the prince, who whispered the name of his bride in his dreams. She was in his thoughts, and the knife trembled in the hand of the little mermaid: then she flung it far away from her into the waves; the water turned red where it fell, and the drops that spurted up looked like blood.

There’s always a contrast between the blue our mermaid comes from and the red of the things she longs for. Illustration by Helen Stratton.

Red and crimson, however are not the colours of the world above: they’re more the colours of the heavenly realm the mermaid is reaching for in her desire do have a soul. Descriptions of the land are left to the third colour we’re concerned about, green, the symbol of everything she doesn’t know of the world above. It’s the colour of hills and forests.

To her it seemed most wonderful and beautiful to hear that the flowers of the land should have fragrance, and not those below the sea; that the trees of the forest should be green…

Lots of illustrators disregard this colour palette and choose to use the green also for the underwater world. This one is by A. Duncan Carse.

3. Places

3.1. The Castle of the Sea-King

Among the description of places, the bottom of the sea and the castle of the sea-king is undoubtedly one of the most beautiful. The bottom of the sea is not a dark bare place, but it’s a colourful kingdom with its counterparts of what we have above: flowers and plants, and colourful fishes instead of birds, and the castle of the king is described as a gothic palace, with windows in clearest amber, a shells roof and pearls.

We must not imagine that there is nothing at the bottom of the sea but bare yellow sand. No, indeed; the most singular flowers and plants grow there; the leaves and stems of which are so pliant, that the slightest agitation of the water causes them to stir as if they had life. Fishes, both large and small, glide between the branches, as birds fly among the trees here upon land. In the deepest spot of all, stands the castle of the Sea King. Its walls are built of coral, and the long, gothic windows are of the clearest amber. The roof is formed of shells, that open and close as the water flows over them. Their appearance is very beautiful, for in each lies a glittering pearl, which would be fit for the diadem of a queen.

I couldn’t track down whether this illustration by Edmund Dulac was in fact for the underwater castle of the Little Mermaid or for something else.

The most beautiful description however is surely the one we get when the Royal Grandmother organizes a court ball for the little mermaid not to be gloomy and sad (after she broke the news that merfolk have no soul).

It is one of those splendid sights which we can never see on earth. The walls and the ceiling of the large ball-room were of thick, but transparent crystal. May hundreds of colossal shells, some of a deep red, others of a grass green, stood on each side in rows, with blue fire in them, which lighted up the whole saloon, and shone through the walls, so that the sea was also illuminated. Innumerable fishes, great and small, swam past the crystal walls; on some of them the scales glowed with a purple brilliancy, and on others they shone like silver and gold.

Illustration by Boris Diodorov. You can see a lot more of them here.

3.2. The Castle’s Gardens

Outside the castle there was a beautiful garden, in which grew bright red and dark blue flowers, and blossoms like flames of fire; the fruit glittered like gold, and the leaves and stems waved to and fro’ continually. The earth itself was the finest sand, but blue as the flame of burning sulphur.

As we have seen, the gardens are another important piece of settings, as they help us focus on the difference between our mermaid and her sisters: the way she arranges her flowers longs for the world above and the statue she has there, with which she starts spending increasingly more time after she has rescued the prince, is another symptom of her longing.

3.3. The Sea Witch’s Swamp

The third “charming” setting we get under the water is the Witch’s bog, with the deadly trees and weeds that are ready to clutch their tentacles around anyone who dares approach.

She fastened her long flowing hair round her head, so that the polypi might not seize hold of it. She laid her hands together across her bosom, and then she darted forward as a fish shoots through the water, between the supple arms and fingers of the ugly polypi, which were stretched out on each side of her. She saw that each held in its grasp something it had seized with its numerous little arms, as if they were iron bands.

3.4. The Castle Above

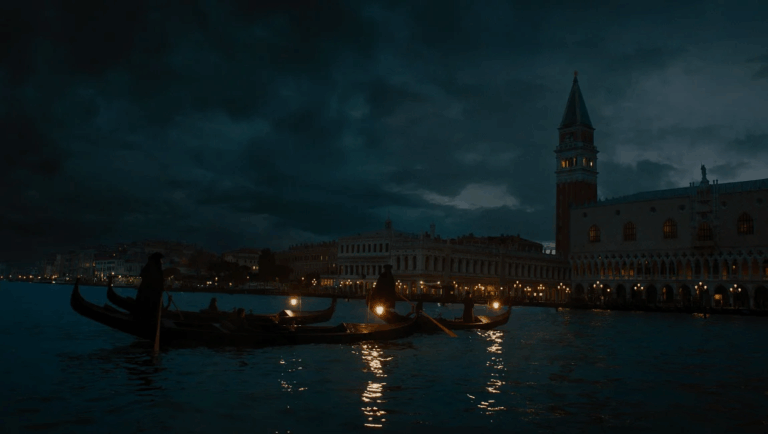

The counterpart of the Sea King’s castle is of course our useless prince’s castle, with its marble stairway leading to the sea, where the mermaid goes to dip her aching feet at night. Coral, amber, shells and pearls are the main materials for the underwater castle: above water, we get yellow stone, marble, silk and glass.

It was built of bright yellow shining stone, with long flights of marble steps, one of which reached quite down to the sea. Splendid gilded cupolas rose over the roof, and between the pillars that surrounded the whole building stood life-like statues of marble. Through the clear crystal of the lofty windows could be seen noble rooms, with costly silk curtains and hangings of tapestry; while the walls were covered with beautiful paintings which were a pleasure to look at. In the centre of the largest saloon a fountain threw its sparkling jets high up into the glass cupola of the ceiling, through which the sun shone down upon the water and upon the beautiful plants growing round the basin of the fountain.

Illustrated Editions

There’s a huge amount of illustrated editions for The Little Mermaid, and it would be impossible to cover them all in just one blog post, but I’ll try at least to give you information on the ones by two of my favourite illustrators: Edmund Dulac, and of course Arthur Rackham. I also added one or two unexpected artists I discovered in writing this article. If you want a complete overview, you can refer to this section of the Surlalune website.

1911: Edmund Dulac

Edmund Dulac was a British illustrator with French origins and one of the most influential artists of his time. He worked on Stories from The Arabian Nights (1907), William Shakespeare’s The Tempest (1908), and The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam (1909). He illustrated The Little Mermaid for a 1911 edition of Stories from Hans Christian Andersen, published in London by Hodder & Stoughton and did not refrain from adding some orientalists touches, which are characteristic of his works. In the book, there are five illustrations to “The Little Mermaid”:

- The Merman King, in which we see the Sea King feeding a pet fish;

- The Little Mermaid Saved the Prince (below);

- The Bright Liquid, where our mermaid swims back from the Sea Witch’s liar with the vial of potion in her hands;

- The Prince Asked Who She Was, where the prince finds the naked mermaid on the marble stairs of his castle;

- Dissolving in Foam, with the tragic ending of our unfortunate maiden.

1914: Dugald Stewart Walker

Dugald Stewart Walker was an American illustrator from Virginia, who illustrated an edition of Fairy Tales from Hans Christian Andersen in 1914 as what probably was his fist significant work.

“I have never been anywhere except Richmond, Virginia, and New York, because I have always been told that only grown-up people were allowed to travel. But the good East Wind and the kindly Moon have taken me on rapturous journeys high above the world to get an enchanted view of things. In this book I have put some of my discoveries”.

(Dugald Stewart Walker’s preface)

His most charming illustrations to The Little Mermaid are in black and white, with heavy symbolistic touches. Take a look at this incredible plate with the tragic ending of the tale: our mermaid ascending with the sisters of air. I really suggest you click to enlarge.

1916: Harry Clarke

Harry Clarke was an Irish from Dublin, who did illustrations and stained glass designs. Though he had been working for years on illustrations for Samuel Taylor Coleridge‘s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Alexander Pope‘s The Rape of the Lock, Fairy Tales by Hans Christian Andersen was his first published work, with 16 colour plates and around 25 halftone illustrations. The plates are nothing special, in my humble opinion, but the black and white sketches are incredible and I already showed you my favourite while I was talking about the Sea Witch. Deeply influenced by art nouveau and symbolism just as much as Stewart Walker, he created incredible and intricated designs playing with water, hair and seaweeds in a decorative way.

Harry Clarke’s illustration of what I suppose is one daughter of the air taking the mermaid into her arms.

I couldn’t find a website collecting all of his illustrations, which I think it’s a shame, so I’ll put a couple here. There’s a rather funny one with the mermaid having tea with what I suppose should be her grandmother…

…and another beautiful one which I can only suppose is one of the sisters’ experiences above water, though I really don’t understand what’s going on with the child in background and maybe this illustration comes from a different story entirely.

1932: Arthur Rackham

Rackham illustrated one edition of Fairy Tales by Hans Christian Andersen with 12 colour plates, 43 inkworks, and 9 incredible silhouettes. As usual, he has a knack for illustrating marginal episodes of the tale, elements that are only mentioned but we don’t see first-hand. It’s the case, for instance, of the encounter of the third sister with human children (below).

“She came across a whole flock of little children”: Arthur Rackham chooses to illustrate the tale of the third and boldest sister.

When it comes to our little mermaid, he chooses to show us hiding behind the marble statue of the boy and, compared to the work of other illustrators, once again he demonstrates the highest possible attention to the text and doesn’t give us the statue of a man, but the statue of a child.

“She put her arms round the marble figure which was so like the prince”: Arthur Rackham captures the fact that the statue is the one of a boy, and the prince himself is sixteen years old.

1941: Kay Nielsen

Between 1937 and 1941, during his stay at Walt Disney’s Studios, Kay Nielsen developed not only the visual styles for the Bald Mountain segment in Fantasia (and some segments that were never to be produced), but also concepts for some things that would eventually be produced, even if with different art supervision: Sleeping Beauty, The Sword in the Stone, and The Little Mermaid. I briefly talked about it here.

For the Little Mermaid, he worked […]. You can see a lot of his original concepts in this article, by Francky Knapp, and here (ignore the ramblings of the guy in the comments, claiming the pictures were stolen and photoshopped from his blog as if he owns the stuff). For a complete gallery of the Disney project, including the early concept, you can refer to this page.

Kay Nielsen gives us a raven-haired little mermaid, with a sylphish look. Her hair would later turn to blonde, until changing to red because it would have been far less interesting to see blonde changing with the shadows below the sea. It was Howard Ashman to suggest the change, along with a great deal of improvement and, allegedly, just as much autobiography as it featured in the original tale: Howard was a homosexual diagnosed with HIV in 1988, halfway through the production of the movie.

No one seemed to remember, at this point, the significance of the colour red in Andersen’s original tale, nor the fact that the fathoms below should have been blue. The final cartoon forfeits the characteristics usage of colours both from the original tale and from Nielsen’s original concept, where the underwater realm features a great deal of purple, both in the sand and in the planting, while the world above seems to be dominated by yellow and gold.

Kay Nielsen’s illustration of the scene where the Royal Grandma (a character completely erased from the final version of the picture) gives the oysters to the little mermaid on her fifteenth birthday.

Kay Nielsen’s concepts for the world above the water are dominated by tints of black, yellow and gold.

Another character who went through a significant amount of change was the Sea Witch, later named Ursula. In Nielsen’s original concept, it’s an octopus/squid with the face of a deep-water fish, but this concept was not considered to be satisfactory. You can read a partial rendition of Ursula’s later development in the words of co-director Ron Clements, here on Insider.

“WIth Ursula, we always thought that the top half would be some version of a human villainess woman, but the bottom half there’s so many different things that we tried…”

(Ron Clemens)

Bruce Morris was one of the main artists working on the later concept, and he went back to the idea of a less animal and more mermaid-like Sea Witch, as Clemens describes. He proposed some very interesting versions of a thin, punk-like witch, taking inspirations from a lionfish, a scorpion fish, and a pufferfish.

“In the script, she was described as a Joan Collinsesque character so all the designs were a very thin, high cheek-boned woman with black hair – a kind of punk biker mumma. She was really freaky.”

(Howard Ashman)

Some of the works were inspired by divas and actresses: Ashman in the quote above mentions Joan Collins, another inspiration was Patti LaBelle, the American singer who originally authored the disco song “Lady Marmalade“.

Ursula, however, couldn’t have been beautiful to begin with, as Ron Clements and his co-director John Musker wanted to leave room for a contrast between her original appearances and her transformation into Vanessa (one of the main differences in Disney’s version is, as it often happens, in introducing a villain to create dramatic tension).

One of the most influential artists in shaping the further development of Ursula was Rob Minkoff, but this is where things get confused. According to some sources, the main inspiration was the Baltimore-born drag queen Divine, whom you might remember as Edna Turnblad in 1988’s Hairspray. According to other sources, the main inspiration came from the biker’s look.

Kevin Lima and Glen Keane took these earlier concepts even further, but at this point Ursula was still one of the merfolk. She was half-fish. Nielsen’s original idea would be brought back by Matthew O’Callaghan, a storyboard artist, who suggested she had to be an octopus. Funnily enough, eight tentacles are too much to animate, so they tuned it down to six with animator Chris Buck. This means that technically Ursula is not half-octopus, but half-squid. The character was eventually animated by Ruben Aquino, a Japanese-born Filipino-American character animator who sadly doesn’t work at Disney anymore.

Paintings and other Stuff

One couldn’t cover in a lifetime all the paintings and different works of arts featuring fish-tailed mermaids. I just drop a couple of my favourite references, hoping you’ll like them too.

1863: Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann

Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann was a Polish who did incredible work, partially inspired by her travels in the Eastern Mediterranean and in the Middle-East. Her patron was Princess Alexandra of Denmark, who later became Princess of Wales, and with her letter of introduction she was able to gain access to lots of private and exclusive elements of Middle-Eastern life, including the harem of Mustafa Fazil Paşa. She was a friend of Hans Christian Andersen and even painted him while he was reading some of his stories to her children. Among her incredible works, she did at least three mermaids and one is more beautiful than the other.

1900: John William Waterhouse

Waterhouse is definitely one of my favourite painters and he did quite a lot of mermaids, alone and in group, with fishermen and without them. He worked quite a lot around one particular red-haired mermaid combing her hair. The final result is one of the most famous paintings he did, currently preserved at the Royal Academy of Arts.

1901: John Reinhard Weguelin

John Reinhard Weguelin was an English figurative painter who did a lot of nymphs and mermaids, alongside a frankly ridiculous amount of classical subjects. In 1893 he did some illustrations to a collection of fairy-tales from Hans Christian Andersen, with sixty-five illustrations. I already talked about this guy when writing about the Wind in the Willows‘ Pan segment. His most famous works around mermaids are watercolours, such as The Mermaid of Zennor (1900), alluding to a local legend, and The Rainbow Lies in the Curve of the Sand (1901).

There’s also a great work from 1906 and a couple of other equally beautiful watercolours from 1911, such as The Sleeping Mermaid.

1909: John Collier, The Land Baby

John Collier was a Pre-Raphaelite painter who specialized in female mythical characters: his most famous works probably are an incredibly powerful Clytemnestra from 1882 (here), a beautiful Circe from 1885 (here), a Lilith with the snake from 1887 (here), and the naked Lady Godiva from 1897 (here). His The Land Baby, from 1909, features a mermaid looking upon a human child on the shore.

John Collier‘s The Land Child presents us the scene from the mermaid’s point of view, both in the title and in the angle.

2 Comments

Anders

Posted at 16:16h, 18 OctoberWhy do you not like Hans Christian Andersen?

shelidon

Posted at 16:18h, 18 OctoberSome of the stuff he did is beautiful, but I don’t like it when he gets patronizing.