Happy Valentine’s Day! For those of you who are thinking that I’m going to do all of them, hold your horses and be realistic: there’s a shitload of them and not all of them are worthy of an article, but some of them are really something worth exploring and “The Witches Frolic” is one of them. I’m talking about The Ingoldsby Legends, I talked about them here when doing an overview on the career of Arthur Rackham and here when I did the first piece on one of the stories, specifically “The Leech of Folkestone”. The other piece I did so far was “The Lay of St. Cuthbert”. Today I’m doing “The Witches’ Frolic”, another piece in verses and, as we’ll see, a highly romantic one.

Yeah, sure…

Illustrated Editions

The tale was widely popular and you can find several editions in which it was published by itself, or in pair with some other tales.

George Cruikshank (1830)

The usual editions include illustrations by John Leech and George Cruikshank. The latter in particular has been circulating also in a coloured version, but it seems to be a reworking of the same picture for Sir Walter Scott‘s Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft Addressed to J.G. Lockhart, Esq. for which you can see some pictures here. An original print of this illustration is preserved at the British Museum and you can see it here.

Jane E. Cook (1876)

This edition puts together two of the Ingoldsby Legends, “The Witches Frolic & The Bagman’s Dog”, was illustrated by Jane E. Cook and published by Richard Bentley and Son in 1876 and there’s apparently an edition at The MET Museum (see here), though no picture is available. I was able to find a picture of the cover from an old auction at Rubylane (equally not available anymore: you have to Google Cache it).

According to this biography on the British Museum website, Jane E. Cook is the married name of Jane E Robins, mother of art critic Sir Theodore Andrea Cook, and she also authored some children’s stories such as The Sculptor caught napping: a book for the children’s hour in 1895 (a trail here, one edition here and another one on sale here). The British Museum has lots of other works authored by her, such as this drawing from 1860, called “Beauty in the Kitchen” or this elegant design for a menu (1860). She seems to have worked also on William Shakespeare’s As You Like It (see the cover here), The Pied Piper of Hamelin by Robert Browning (see here the page, though there’s no picture) and on Pipkin’s Rustic Retreat: A farce in one act by one Thomas John Williams (see here). Even if there are no pictures available, the same archive tells us that Jane worked also on other Ingoldsby Legends such as “The smuggler’s leap” (here).

One of my favourite works from Jane Cook at the British Museum (you can see it here)

Ernest M. Jessop (1888)

There’s a 1888 beautiful edition, for instance, with illustrations by Ernest M. Jessop, which was dug up in 2012 by Side Real Press and you can see 20 pages here (thanks to this more visible website for cross-posting). This is defined as «a large format edition», and «one of a series».

This is just the frontispiece, giving us a couple of additional information such as the name of Eyre & Spottiswoods, established by William Strahan in 1739 and defined Her Majesty’s printers as in 1845 it received the appointment to print for Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. There’s a book about them and you can read it on-line here (The story of a printing house; being a short account of the Strahans and Spottiswoodes by Richard Arthur Austen-Leigh). They later became a bunch of assholes, being the first printer in Britain to print The Protocols of the Elders of Zion in 1920, with the additional subtitle The Jewish Peril. So, fuck them.

Regardless of their subsequent downfall, this edition is wonderful and one example is preserved at the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco (you can see it here) and below I give you one of the inner pages. There are illustrations occupying often a half of the page and beautiful lettering, with additional small illustrations between the lines.

I did a bit of digging to try and figure our what is this series of publications and I was able to find out other books with the same illustrator and focusing on other Ingoldsby Legends, such as:

- “Ye Jackdraw of Rheims. An Antient Ballade” (see here and here on auction, and some pictures here);

- “Misadventures at Margate. A Legend of Jarvis’s Jetty” from 1890 (on sale here and on auction here);

- “Netley Abbey” from 1889 (see here);

- “The Knight and the Lady” (see here);

- “The Lay of St. Aloys” from around 1850 (see here), which is absolutely stunning.

As far I was able to understand, Ernest Maurice Jessop was publishing also on The Sketch magazine (see here 64 silverpoint etchings and sketches for royal pets) and there’s little biographical information about him, if ever. Among his other works, we can find illustrations for The Rosebud Annual from 1897 by James Clarke (you see pictures here and the book is currently on sale here, though none of the scanned illustrations seems to be from our guy), but I’m not even sure it includes original works and not a selection of illustrations already done for those Ingoldsby Legends listed above.

Arthur Rackham (1898)

Rackham is the main reason we are dealing with these legends and, as I already mentioned, he worked on them for a 1898 edition. He did both coloured plates, and black and white: as it often happens with Rackham, some black and white illustrations were later re-worked in colour (such as the one below, for which you can see the coloured plate here). For this reason, the original inked illustrations are rather difficult to find and they were published by this website.

Here you have another version of the same scene, inked monochrome with no shading.

Herbert Cole (1903)

Herbert Cole was was an English illustrator who worked on books such as the John Lane edition of Gulliver’s Travels in 1900 and The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, probably his most famous work. More on the author can be found here, alongside the title piece for “The Leech of Folkestone”. You can also see some of his works in the archives of the British Museum.

It was rather hard to dig up much on his work on The Ingoldsby Legends and I couldn’t find anything specific to “The Witches’ Frolic”, but considering his funny and macabre style, and his passion for cats, I found hard to believe that he didn’t do anything so, after a little digging, I could find this edition with pictures of the inside and there it is, one illustration for the moonlight broomstick ride.

Other curiosities

There’s also trace of a painting done by one Walter Winlens in 1878 on a charger, which is a large flat plate, and you can find it on auction here. It features two cats dancing and one cat playing the bagpipes, so it might be worth its money.

A quote from The Ingoldsby Legends was also used in a piece called “The Witches Frolic” published in The Tatler, on September 23rd 1936. It was the subtitle to a beautiful illustration by Alfred E. Bestall, mostly known to be the author of Rupert Bear. His work seems to be deeply influenced by the style of Arthur Rackham, but unfortunately his Trust is obsessed over not publishing his works on the internet and there’s very little you can find around. Here you have the reproduction of the page in question, alongside the transcription of what it says.

Witches were always initiated by others and Mr Bestall’s fanciful and attractive picture suggests the novitiate of a young “malefica”.

What’s a Frolic, precious?

The most famous occasions on which Witches get together is usually called a “sabbat”, but a sabbat is a gathering on specific occasions, and not just any gathering. Occasional gatherings, impromptu parties, are called “Esbats” and the word apparently comes from the Old French s’esbattre, meaning to frolic. For the non-English speakers, here’s the proper definition.

frolic

verb

UK /ˈfrɒl.ɪk/

present participle frolicking | past tense and past participle frolicked

to play and behave in a happy way

Witches gathering

The Witches gathering is a topic that fascinated writers since the ages of Shakespeare’s Macbeth. The Basque term for this kind of gathering is Akelarre and the French one is sometimes derived from words such as sabbatha or synagoga, but the term sabbath apparently doesn’t appear until Henry Charles Lea‘s History of the Inquisition (1888): each time you find it used before, it’s most likely a translator’s choice for something else, as it happens in translations of both Friedrich Spee‘s Cautio Criminalis (1631), who uses the generic word conventibus, and Heinrich Kramer‘s Malleus Maleficarum (1486), in which he uses the word concionem, again a generic term for a gathering. Even for artworks the term is often used in spite of the original one: Goya’s famous work uses the Basque term (the other famous one being this one).

Francisco Goya – Aquelarre (1823)

Among the painters who mostly worked on witches’ subject, before romanticism and symbolism, it’s well worth mentioning Frans Francken the Younger, a Flemish painter mostly known for his altarpieces, painted furniture and cabinet pictures, but whose genre paintings were highly innovative in both technique and subjects. In particular, his series of Witches’ Kitchens from around 1640 is a delight.

Frans Francken the Younger, The Witches’ Kitchen (1640)

On the theme of a Witches’ Kitchen, I suggest you also take a look at this beautiful work by Cornelis Saftleven, below. He also did some neat work portraying Hell (see Rich man descending into hell, currently at the National Museum in Warsaw) and the Temptations (see this Job plagued by Evil Spirits, this Temptations of Saint Anthony and, most notably, this one), and worked on a Witches’ Gathering that doesn’t seem to be going too well and that you can see here.

His scenes are similar to lots of works by David Teniers the Younger, such as this Preparation for the Witches’ Sabbath (round 1640), his incredible Mad Meg, his scene where witches are being helped by a beaked creature to dig a grave (you really don’t want to know), his Kitchen, his initiation of a young lady, and a glorious cauldron scene from 1635.

David Teniers the Younger, such as this Preparation for the Witches’ Sabbath (round 1640)

Witches gathering in ruins

The idea of witches gathering in ruins, as we’ll see in this Ingoldsby Legend, is not new in art. Dutch painter Jacob Isaacszoon van Swanenburg was one of the first artists of blending together the taste for the supernatural and the taste for ruins, only it was say before anyone had even a glimpse of Romanticism: van Swanenburg was old enough to be teacher of young Rembrandt. He’s famous for his biblical and apocalyptic scenes, such as The Last Judgment and the Seven Deadly Sins, the visionary Temptation of Saint Anthony, The Sibyl showing Aeneas the Underworld and The Harrowing of Hell, but the work I’m referring to is Witches’ Sabbath in Roman Ruins, for which in 1608 he got in trouble with the Inquisition of Naples. There are some very small reproductions, around, and you can read this guy trying to find them for an exhibition called “Bruegel and witchcraft in the Low Countries” at the Musea Brugge in 2014.

Jacob Isaacszoon van Swanenburg, Witches’ Sabbath in Roman Ruins.

The topic was also elaborated upon by Claes Dircksz van der Heck, a Dutch landscape painter of the so-called Golden Age (1581 – 1672), for works such as this one (1636) currently preserved at the RijksMuseum, for which I give you a lower detail.

Claes Dircksz van der Heck, Witches’ Sabbath in a ruine.

Witches flight

On top of the idea of witches gathering in some ruins, the other trope we can find in this Ingoldsby Legend is a glorious scene of witches’ flight, also something which fascinated artists. Sometimes witches are portrayed with having wings, where witches are similar to winged demons of Greek tradition such as the harpies, sometimes they’re flying on top of something (like this witch flying on goat by Albrecht Dürer) sometimes they’re simply flying, with no explanation whatsoever, as in this El vuelo de brujos by Goya and in his Volavérunt (Caprice nr. 61).

Here, however, we’re looking for witches flying on broomsticks, and the theme doesn’t seem to be significant before the romantic period, aside from Goya’s Linda Maestra in the Caprichos. A grand broomstick painter is without any doubt Luis Ricardo Falero, Duke of Labranzano, which between 1878 and 1882 painted a whole series of flying witches on broomsticks, the most significant of them being this turbulent flight from 1878, and this red-headed witch with a torch from 1880, also used as a subject for this decoration of a tambourine in 1882.

Luis Ricardo Falero, The witch painted on a tambourine (1882)

Another well-known work, also including cats, is Théophile Steinlen‘s, a Swiss painter operating in France within the circle of the famous Chat Noir in Bohémienne Montmartre and author of the famous Chat Noir poster I’m sure you have seen a thousand times on all kinds of merchandising. The work I’m referring to is called Metamorphose, from 1893, and is sometimes used as an illustration for Bulgakov‘s Master and Margarita.

Théophile Steinlen, Metamorphose (1893)

Similar subjects were painted by Albert Joseph Pénot, a guy who mostly specialized in female nudes and landscapes as if they were the same thing. The most important work of this kind is his Départ pour le Sabbat (1910).

Albert Joseph Penot, Départ pour le Sabbat (1910)

Another interesting work is Edith Maryon‘s sculpture To the witches’ revels, a platinated bronze dated around 1909, put on auction here and currently in a private collection. There’s also a plaster sculpture of the same subject from 1904, which appeared as a black and white picture illustrating Per Faxneld’s Satanic Feminism: Lucifer as the Liberator of Woman in Nineteenth-Century, and which is mistakenly believed to be the same thing.

A more stereotypical sorceress, Witch and a Cat on a Broomstick (1904), was sculpted in England by Edith C. Maryon. With its use of clichés like the broom and cat, it brings to mind the witch of Victorian fairy tales, but reinterpreted as young and pretty like a kindly fairy queen. The dreaming and mysterious expression on her face has echoes of the Pre-Raphaelite witches, though here coupled with the naked, risqué variety popular with certain other artists. There is, however, little of the sinister carnality often seen in such a context here, and Maryon’s witch appears quite innocent – a figure of whimsy rather than an erotic nightmare from the age of the witch trials or the depths of the Decadent imagination.

Faxneld’s work is reeking bullshit, but he gives us some useful biographical information on Maryon, such as her association with Rudolph Steiner and her involvement in the design of the building known as the Goetheanum.

In illustrations, the subject is even more popular than in paintings and the earlier example has to be in Martin Le Franc‘s Le Champion des Dames (1451), a huge composition in verses originally dedicated to Philip the Good and narrating the deeds of women across history. Illustrations and other decorations (which are called illuminations when it comes to manuscripts) were done by Peronet Lamy.

Peronet Lamy, illustration to Martin Le Franc‘s Le Champion des Dames (1451)

Since it’s virtually impossible to give you all significant illustrations of tales involving witches’ flight, and more specifically witches flying on brooms: I’ll just give you a rough timeline of the works I like most and of the ones I found more interesting.

1870. William Holbrook Beard, The Witches’ Ride.

Beard was an American painter whom I think you should know at least for his animals in human clothes (way before Disney came along). Oddly enough his witches are all human, but his scenery is still humorous, with them not seeming to be completely flight-savvy and slippers flying around.

1900. Jean Veber, a French caricaturist who worked in newspaper like Gil Blas, L’Assiette au Beurre and Le Rire. In 1900 he did this Les Sorcières ou Tandem, and some other of his works from the fantastic and the grotesque can be seen on this blog.

1901. James Torrance gives us a witch in 1901 in his illustrations to Sir George Douglas’ Scottish fairy and folk tales, specifically to the fairy tale “Witches of Delnabo”, which you can read on-line here: basically the farm of Delnabo is proportionally divided between three heirs and the wives of the tenants are tempted to find a way to end their poverty.

To this order of the black pair the bride was resolved to pay particular attention. As soon as they were embarked in their riddles, and had wriggled themselves, by means of their brooms, into a proper depth of water, “Go,” says he, “in the name of the Best.” A horrid yell from the witches announced their instant fate–the magic spell was now dissolved–crash went the riddles, and down sank the two witches, never more to rise, amidst the shrieks and lamentations of the Old Thief and all his infernal crew, whose combined power and policy could not save them from a watery end.

1911. Historian Jules Michelet, wrote La Sorcière (known in English as Satanism and Witchcraft because of creative translations) in 1911 and the work was illustrated by Martin van Maële, a guy mostly known for his erotic twist on illustrations. He was the man for the job, since the book seems to have a knack for describing young ladies on top of altars. It was a book mostly defending the birth of witchcraft as a resistance practice against the vexations of both feudalism and the Roman Church.

The object of my book was purely to give, not a history of Sorcery, but a simple and impressive formula of the Sorceress’s way of life, which my learned predecessors darken by the very elaboration of their scientific methods and the excess of detail. My strong point is to start, not from the devil, from an empty conception, but from a living reality, the Sorceress, a warm, breathing reality, rich in results and possibilities.

1919. Arthur Wilde Parsons, Any Old Fairy Tale.

Born at Stapleton, Gloucestershire, in 1854, A.W. Parsons is a genre painter who mostly specialized in marine landscapes. He visited Italy in 1911 and this influenced his Venetian scenes such as this one. Works not depicting a scenery are rather uncommon, but not impossible to find: some interesting stuff is for instance this scene of a reading inside a forge, or this one of an old lady inside a cottage.

1935. Paul Frederick Berdanier‘s The Witches’ Sabbath a la Mode, preserved at the Smithsonian, is one of the illustrations he did for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and it’s not unique in its genre: a war cartoon, semi-propagandistic, using mythological and fantastical themes. I believe we have seen a Neptune by Ernst Shepart in a similar fashion.

Young and Older Witches

Another idea, as we’ll see, is the mixture of young and old witches, of masters and one acolyte. It’s usually appearing in paintings as a corruption of youth, but nevertheless it’s interesting to take a look at it, and there are exceptions. Louis-Maurice Boutet de Montvel, a French painter and watercolourist who also worked a lot in illustrating children’s books, in 1880 did a beautiful La leçon avant le sabbat, in which the young lady is portrayed as a refined student and the teacher has very little of the usual groctesque characteristics of old hags in previous paintings. Just compare it to this Young Sorceress from 1857 by Antoine Wiertz and see what I mean.

The Tale

The Places

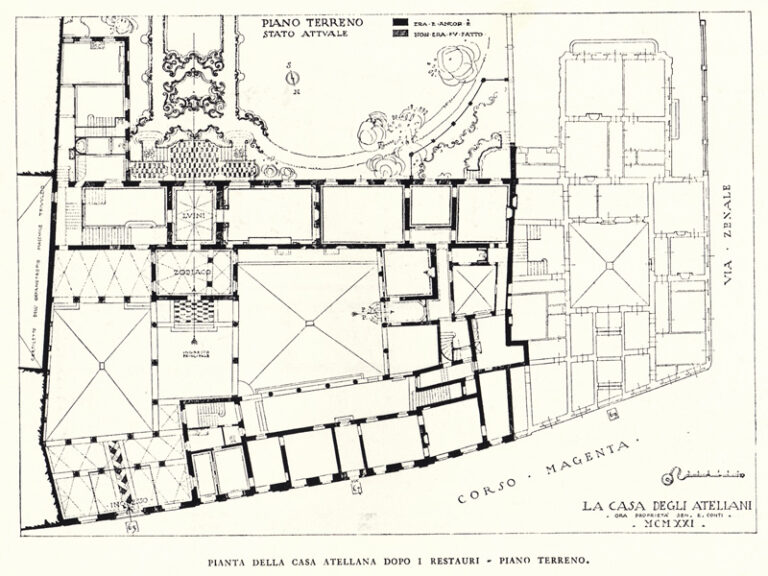

The tale is set in Tappington Hall, the fictional place from which the author is saying to come from and, later, the XVI Century non-fictional Jacobean timber-framed house in Denton (Kent) where Richard Barham resided. It is framed as a tale within the tale, however, with a grandfather telling the story to little Ned. The ruins are the remains of a Preceptory once belonging to the Knights Templars situate near Swingfield, once spelled Swynfield or Swinkefield, in the same Kent district of Folkestone and Hythe. A preceptory is the headquarters of orders of monastic knights and this one, also called St John’s Commandery, was taken over by the Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem in 1180, thus evicting the nuns and sending them to the Buckland Priory. It was suppressed during Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries, which we already mentioned talking about “The Leech” story. The Priory is currently a II Grade listed building in English Heritage.

Other mentions are «the Fair of good Saint Bartlemy», a reference to the infamous Bartholomew Fair, one of London’s charter fairs in Summer which took place within the precincts of the homonimous Priory founded by Rahere under the grant of Henry I. The fair continued even after the infamous Dissolution, within a piece of land granted to the Church of St Bartholomew-the-Great. It was originally a three-day event, with merchants mostly dealing in cloth (this also gives the name to a street in London), but became a two weeks thing in the XVII Century only to be shrunk back to four days in 1691. In 1753 it was moved from August, 24th to September, 3rd and it became a pleasure fair, with all sorts of activities one might expect from a fair nowadays.

«Hither resort people of all sorts, high and low, rich and poor, from cities, towns, and countries; of all sects, papists, atheists, Anabaptists and Brownists: and of all conditions, good and bad, virtuous and vicious, knaves and fools, cuckolds and cuckoldmakers, bawds and whores, pimps and panders, roughs and rascals.»

– invitation to the fair in a 1641 pamphlet quoted here

It was suppressed in 1855, but not before giving us marvellous settings for tales like Daniel Defoe‘s Moll Flanders (1722) and Wordsworth’s The Prelude (1805). In 1614 it was the setting of a play, a Jacobean comedy by Ben Jonson, which was performed at the Hope Theatre by the Lady Elizabeth’s Men, and the English scholar Henry Morley, famously one of the earliest professors of English literature in Great Britain, wrote a book called Memoirs of Bartholomew Fair, with engravings by the Brothers Dalziel (business name for George and Edward, later joined by their sister Margaret and their other brother Thomas). You can read it on-line here.

It is also mentioned in Samuel Pepys in his diary because, to quote a wonderful and incredibly underrated movie…

…if two mice were fucking in a nutshell, [Pepys would] find room to squeeze in and write it down.

There’s a nice article about the fair here (it’s in Italian, so you might have to Google-translate it).

The Time

It is unclear what time and what year is it, when the story starts, but Grandpa gives us a specific time for the tale he’s telling.

One night –‘ twas in Sixteen hundred and six —

I like when I can, Ned, the date to fix,–

The month was May,

Though I can’t well say

At this distance of time the particular day —

1606 was not a quiet day for England: after the so-called Gunpowder Plot, where a group of Catholics led by Robert Catesby tried to blow up the House of Lords during the State Opening of Parliament, a trial for treason began and Guy Fawkes, a veteran who had been given the responsibility of placing the charges, became the symbol of the whole affair. You know the guy because his mask is the one you have seen in V for Vengeance. Fawkes was put on trial on January, 24th, found guilty and executed on January, 31st alongside his co-conspirators Robert Keyes, Ambrose Rokewood, Thomas Wintour. The events play a central role in British folklore: November, 5th is called Guy Fawkes Night, or Bonfire Night, an annual commemoration celebrating the survival of King James I to the attempted coup.

Anyway, it’s May 1606. A dark and stormy night, as Snoopy would say.

But oh! that night, that horrible night!

Folks ever afterwards said with affright

That they never had seen such a terrible sight.

The Tale

The story starts with a lover, one Robin Gilpin, «a wild and roving lad», and this lover is waiting in the pouring rain for her beloved, around the ruins of the deserted Abbey.

Rob Gilpin ‘was a citizen;’

But, though of some ‘renown,’

Of no great ‘credit’ in his own,

Or any other town.

He’s waiting for Miss Gertrude Slade, who looked out of the window, saw the pouring rain and decided no-one in their right might would go out, let alone wait, in that kind of weather.

Unfortunately, our Gilpin is not in his right mind, and he is indeed waiting.

Robin looks east, Robin looks west,

But he sees not her whom he loves the best;

Robin looks up, and Robin looks down,

But no one comes from the neighbouring town.

While he’s pacing there, waiting and getting soaked through his useless umbrella by the pouring rain of the fierce thunderstorm, «half dead with cold and with fright», he sees «a twinkling light» and approaches the place where, as it turns out, three witches are consorting.

And there were gossips sitting there,

By one, by two, by three:

So far so good, but the third one is a young raven beauty and our good Robin is a goner in like two seconds.

Two were an old ill-favour’d pair;

But the third was young, and passing fair,

With laughing eyes and with coal-black hair;

A daintie quean was she!

All three of them are wearing a green kirtle, which is a sort of an apron, specifically in Lincoln Green, which is a dye coming from the town of Lincoln, in England, and that was particularly popular during the high Middle Ages. It was obtained by combining the bright blue coming from woad, also known as Asp of Jerusalem, with a yellow dye coming from weld, a weed also known as dyer’s rocket, or with the dye extracted from another weed, more witchly known as dyers’ broom. It firstly appears in literature in Geoffrey Chaucer‘s “Friar’s Tale” (part of the Canterbury Tales, around 1400) and is still recorded as a popular colour around 1510, but in XXVI Century it was already an outdated, out of fashion colour. It is often used to depict an old-fashioned costume, as it happens in Edmund Spenser‘s The Faery Queene, and its usage on the witches’ kirtle (also not particularly à la mode) is meant to tell us that the three ladies are not dressed fancily.

Their appearance is completed with the traditional pointy-hat, here called «steeple-crown’d hat», the birch broom and one black cat each.

Our Robin is frightened out of his pants, but the younger witch calls him by name and invites him in, welcomes him, and asks him to dance (or, more specifically, to «tread a measure»).

Measure: Regulated division of movement.

(Dancing) A regulated movement corresponding to the time in which the accompanying music is performed; but, especially, a slow and stately dance, like the minuet.

Tread a measure: to dance

Our lad doesn’t need to be asked twice: he grabs the young witch’s hand and off they go, «though Satan himself were blowing the pipes».

Now around they go, and around, and around,

With hop-skip-and-jump, and frolicsome bound,

Such sailing and gilding,

Such sinking and sliding,

Such lofty curvetting,

And grand pirouetting;

The music itself is not particularly nice, though our good man doesn’t seem to mind: it’s a melody of «dying man’s groans», «rattling of dead men’s bones», and shrieks, and squeals, and squeaks.

And around, and around, and around they go,

Heel to heel, and toe to toe,

Prance and caper, curvet and wheel,

Toe to toe, and heel to heel.

Since dancing is good for one’s appetite, they soon start wondering what to do next, in this merry night of frolic. So, again, you might find materials to organize a themed menu featuring:

- mutton and veal;

- partridge, and widgeon, which is basically a duck, and teal, another kind of duck;

- deer pasty: you can see some recipes here, including some very old ones from Hannah Woolley‘s famous The Queen-Like Closet from 1670 and Robert May‘s The Accomplisht Cook from 1660;

- grouse pie, one of the most delicious things ever (see a modern recipe here): a grouse is basically a pheasant and if you have never eaten one, you have never lived;

- Florentine, a very thick T-bone steak which is usually prepared rare (and I can’t believe Wikipedia knew nothing about it, I had to put it there);

- roast goose;

- turkey, which were introduced in England some time after 1540;

- chine, which technically is just another way to say a piece of meat.

All accompanied with ale from the cellars, lamb’s-wool (an early variety of wassail – mulled cider and spices – brewed from ale, baked apples, sugar and various spices like cinnamon, nutmeg, and ginger), eau de vie (a fermented and double-distilled fruit brandy), Malvoisie and Clary wine.

The menu thus listed seems to be appealing enough, so the witches take flight and go visit all the people who might have something to eat and to drink: in the pantry of Sir Thopas the Vicar, they find:

- «turkey-poult larded with bacon and spice», where the poult is simply a baby turkey;

- «a New-College pudding of marrow and plums», for which you can find a recipe in English Housewifry by Elizabeth Moxon (1764) and in A Shilling Cookery for The People by Alexis Soyer (1845) both listed here along with a quote from this very legend;

- chicken breast;

- grouse pie with hare, also called a «leveret» (a young hare).

Note that in this list it gets also mentioned William Kitchiner, as «Doctor Kitchener», author of Apicius Redivivus, or the Cook’s Oracle, but this is a little anachronistic, as Kitchiner’s book will not be published until 1817 and grandpa claims to be telling the story of his grandfather in 1660.

While they’re drinking and toasting to «’Scratch,’ and ‘Old Bogey,’ and ‘Nick.’», all nicknames to mean the devil, our Robin stands and screws up proposing a toast of his own:

‘A bumper of wine!

Fill thine! Fill mine!

Here’s a health to old Noah who planted the Vine!’

The mention of Noah is referring to the Genesis where Noah plants a vine-garden, drinks the wine, gets wasted and is found naked and asleep by his three brothers (one of whom does not behave very nicely). The very name of the prophet, however, is enough to have the witches choking on their wine and break the spell: everyone in the Vicary wakes up.

Up jump’d the Cook and caught hold of her spit;

Up jump’d the Groom and took bridle and bit;

Up jump’d the Gardener and shoulder’d his spade;

Up jump’d the Scullion,– the Footman,– the Maid;

(The two last, by the way, occasion’d some scandal,

By appearing together with only one candle,

Which gave for unpleasant surmises some handle;)

Everyone shows up, none particularly dressed, to see what’s the racket in the pantry, and the witches take flight again and flee, leaving our poor Robin there to be mauled, and kicked, and pricked, and in short captured by the people in the house.

The morning afterwards, our Robin is dragged at Tappington Hall to appear in front of the Squire and be held responsible of the ransacking of the Vicar’s pantry and having done so in «queer» company to say the least: the evidence is strong and things are not looking good for poor Robin, as the tale grows bigger and bigger, until he is described as having consorted with two thousand witches and, «with force and with arms, and with sorcery and charms» having looted two thousand cellars and two thousand pantries, having terrorized twenty-thousand in-dwellers and having uncorked ten thousand bottles.

At last, Madge Gray shows up, grabs the broom exhibited as proof of Rob’s crime, grabs the poor fellow too and rescues him, by flying away through the chimney.

Robin is then found near the ruins, with a kick-ass hangover.

Rob from this hour is an alter’d man;

He runs home to his lodgings as fast as he can,

Sticks to his trade,

Marries Miss Slade.

The moral of the tale is along the lines of: don’t flirt with young ladies and don’t drink too much.

Don’t meddle with broomsticks,–they’re Beelzebub’s switches;

Of cellars keep clear,–they’re the devil’s own ditches;

And beware of balls, banquettings, brandy, and — witches!

You can read the full story here.

People mentioned

There’s a lot of people mentioned in the verses, some of them just passing by and others are referenced as if you should know what he’s talking about. It’s a mixture of very famous historical characters and authors, obscure people and people who were famous at the times the Legend was written and published, but whose names might tell very little to us. I try and provide you with a navigational chart.

Historical Characters

Kings and Queens

The first historical character mentioned is King James I, of course, with regards to the «golden days» (or not so golden, perhaps). King James «held in abhorrence tobacco and witches», according to the narrator, and his days (golden or not golden) are compared with the previous period of Good Queen Bess, the second historical character mentioned after him. The sentence «Good Queen Bess» is of course a reference to Queen Elizabeth I. The third one is her father, Henry VIII, in explaining why the abbey is empty and in ruins, and there are no friars: it’s a reference, as we know by now, to the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

The Dissolution of the Monasteries in a 1536 document preserved at the British Library.

Italic Tribes and Roman leaders

For some reason, the legend doesn’t stop to British history. When the witches are escaping from the cellar, the promptness of their flight is compared to the one of the Volsci (called «Volscians») from their town Corioli, in a reference to the year when Gaius Marcius Coriolanus captured it in 493 B.C. and god his “surname” from it. This might also be simply the reference to the play Coriolanus by Shakespeare, as we’ll see there are other Shakespearian references. This idea is also reinforced by the following reference to Shakespearian actor William Macready.

Chinese merchants

When we are in the court awaiting judgement, the narrator goes on a digression about the fact that breakfast was rather different because tea hadn’t been “invented” yet. In doing so, he mentions Wu “Howqua” Bingjian, and the Hong merchants: former richest man in the world before Scrooge McDuck came along, Wu was the leader of the Cohong (merchant Guild) in Canton and the most important merchant in the so-called Thirteen Factories, a region along the Pearl River in southwestern Guangzhou. During the First Opium War, in mid-XIX Century, he traded with the British Empire and earned his fortune by trading in silk, porcelain and, of course, tea. He was so rich that he contributed for one third of the incredible sum of money defined as war compensation to the British during the Treaty of Nanking.

George Chinnery, the only western painter allowed to reside in South China during the XIX Century, did a famous portrait of him around 1830. Alongside “Mr. Howqua”, he painted some of the most infamous Scottish opium traders such as William Jardine and James Matheson, who were central in the events unfolding after the 1839 incident and the subsequent First Opium War.

The teas mentioned in this Ingoldsby Legend, while talking about the misery our ancestors had to suffer in not having tea for breakfast, are the Lapsang souchong (a black tea of smoke-dried Camellia sinensis from the Fujian Province), and the Bohea, trade name of Wuyi tea (a broad naming including both black and oolong teas, from plants growing in the Wuyi Mountains).

Myths and Fairy-Tales

Thetis

Historical characters are not the only people mentioned in the tale. In describing the sunset, our narrator chooses to do so by personifying the Sun and invoking the Greek character Thetis as a goddess of the sea.

The Sun had gone down fiery red;

And if that evening he laid his head

In Thetis’s lap beneath the seas,

He must have scalded the goddess’s knees.

Thetis is usually a sea nymph, one of the 50 Nereids (the daughters of Nereus and Doris, two ancient sea-gods), but it’s not uncommon to see her depicted as a goddess in more Archaic traditions. In the Iliad, where Thetis features a lot being the mother of Achilles, she is often referred to as a goddess and her son tells us how she held the throne of Zeus and defended him against a rebellion plotted by his sister and consort Hera, his brother Poseidon and his daughter Athena. She ends up marrying a mortal to defuse the prophecy according to which that her son would become greater than his father, through a plot of both Zeus and Poseidon: this mortal is Peleus, and he is able to subdue her under advise of Proteus, another sea god. In this occasion, Thetis is described as being a shapeshifting deity, able to assume the form of fire, water, a lioness and a serpent. The scene is described by Ovid in his Metamorphoses.

Their wedding is one of the events which sets in motion the War of Troy: it is her and her husband who forget to invite Eris, the goddess of discord, who drops on the table the golden apple, springing the competition on who’s the fairest of them all between Hera, Athena and Aphrodite.

The most famous depictions of Thetis in art is probably Dominique Ingres‘ painting from 1811 where the goddess is shown kneeled at the side of a Jupiter who doesn’t seem to give a fuck about anything. The idea that the Sun sleeps with the nereids and gets up in the morning to go to work is, however, better painted by François Boucher, a French rococo painter who did exquisite work in immortalizing the ass of Marie-Louise O’Murphy, one of the petites maîtresses of King Louis XV of France. His Le Lever du Soleil (The Rising of the Sun) was painted in 1753 and is currently preserved at the Wallace Collection in London.

Beelzebub gets also mentioned often, with regards to the witches, but I do believe I already wrote enough about him in my piece on the “Lay of St. Cuthbert”.

Artists and Writers

He left behind him a lurid track

Of blood-red light upon clouds so black,

That Warren and Hunt, with the whole of their crew,

Could scarcely have given them a darker hue.

Dancers (and their husbands)

When Robin is dancing with the young witch, their dance is described as good enough to «swear that Monsieur Gilbert and Miss Taglioni were capering there». The reference is to the Italian ballet-dancer Marie Taglioni, Comtesse de Voisins for having married Comte Auguste Gilbert de Voisins (to be honest, theirs was a brief endeavour: they were married in 1835 and separated 1836, when she gave birth to an illegitimate child, but never divorced and her two sons were recognized by Gilbert). Her figure is better described in this article.

1840. The Three Graces: Marie Taglioni as the Sylph (La Sylphide), Fanny Elssler as Florinda (Jean Coralli’s ballet Le Diable boiteux, 1836) and Carlotta Grisi as Béatrix (La Jolie Fille du Gand by Adolphe Adam, 1842).

Shakespeare

Shakespeare’s Macbeth gets mentioned explicitly at least once, as you might expect in a work featuring three witches, but not in the way you might expect. The quote comes when the household discovers the witches (and Robin) in the cellar.

With upstanding locks, starting eyes, shorten’d breath,

Like the folks in the Gallery Scene in Macbeth,

When Macduff is announcing their Sovereign’s death.

Still, our three witches Goody Jones, Goody Price, and Madge Gray are probably three in honour of Shakespeare’s Macbeth and his main source, Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland (1587), one of the first collaborative collections of folklore which also served as a source for writers such as Christopher Marlowe, Edmund Spenser and George Daniel.

Sir Walter Scott

One touch to his hand, and one word to his ear,–

(That’s a line which I’ve stolen from Sir Walter, I fear,)–

The reference, as far as I could find out, it’s from Sir Walter Scott‘s Marmion: A Tale of Flodden Field, a poem published in 1808 but set in XVI Century Britain (the poem ends with the Battle of Flodden, 1513). The story is an intrigue featuring Lord Marmion, a favourite within the graces of Henry VIII, and his obsession with the wealthy Clara de Clare: with his mistress Constance De Beverley, Marmion tries to implicate Clara’s fiancée in a scandal. There’s exiled lovers, corrupted nuns who get walled up alive, duels, battles and a happy ending. It served as an inspiration to one of the tackiest, most infuriating works of bigotry ever known to Italian literature: I Promessi Sposi by Alessandro Manzoni, a text which gets regularly taught at high school (you have to undergo a whole year during which you read and analyse it all), and in which it’s explicit theorized that poor people and women will go to hell if they rebel, and the good thing is for them to accept their condition and be pious about it. Of course Manzoni was a nobleman. Anyway, it’s not Walter Scott’s fault: his poem has heroism, knighthood and chivalry.

Lawyers and Jurists

When we are in Tappington Hall and the court is assembling to judge our poor fellow Robin, lots of authors and jurists are mentioned with reference to the Squire’s library: Fleta is the name with which it’s referred a Latin treatise on the common law of England, probably dating around 1290; Bracton refers to Henry of Bracton, a XIII Century English jurist who was the advisor of of Henry III and wrote a lot (like really a lot), and is mostly famous for his De legibus et consuetudinibus Angliae; Coke is without any doubt a reference to Sir Edward Coke, a judge generally considered the greatest jurist of the Elizabethan and Jacobean period, who led the prosecution in the Gunpowder Plot trial and authored several treaties including the four-volume Institutes of the Lawes of England (1628 – 1644); Lyttleton is a whole dynasty of people, but the famous jurist is Sir Thomas de Lyttleton, who wrote a Treatise on Tenures (around 1466) attempting a scientific classification of the rights over land.

In the front of his seat a

Huge volume, called Fleta,

And Bracton, both tomes of an old-fashion’d look,

And Coke upon Lyttleton, then a new book;

Interestingly enough, only one author is contemporary to the narrator (Sir Edward Coke): all other treaties are old as fuck, which is probably a good hint on the kind of justice our poor fellow Robin is about to receive.

Arthur Rackham’s Witches

Since Arthur Rackham is the reason we’re all here in the first place, I’d like to spend some words in his witches and on the many occasions in which he had the chance to illustrate this subject, because the Ingoldsby Legends is far from being the only occasion. There’s a monographic article also here.

Another Ingoldsby Legend in which Rackham gives us a witch is “A Nurse’s Story – The Hand of Glory” with this witch…

…and her mandatory mob.

But witches were one of Rackham’s favourite subject, almost like twisty creepy trees and dancing fairies. So let’s see which other chances he got to dabble in the topic. It’s not by chance that he pictures himself almost plagued by witches from his work and his imagination in this 1912 self-portrait.

I can’t promise I’ll be exhaustive, but I’ll sure try.

1904. The Witch’s Pool

I don’t know which work is supposed to illustrate, if any, but one of the first witches I was able to dig out after the 1900 Grimm’s legends is this watercolour of a witch charming what looks like a Marsh’s pool. You can find it on auction here. In the same website, it’s quoted the opinion of a critic appeared on the Birmingham Post, on April, 9th 1904.

‘…beyond dispute a master of his craft, and he occupies a position no one can be said to share with him’

1909. The Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm

You can see the whole set of illustrations from this collection here or here. Within these Fairy Tales, Rackham’s witches are significantly less witchy. No pointy hats, no brooms: just old-fashioned hags with checkered aprons and handkerchiefs on their hair. See for instance this illustration for “Rapunzel”…

…and we also meet the witch in another occasion, lurking behind a wall.

When he went over the wall he was terrified to see the Witch before him

See also these two for “Hansel and Gretel”.

“Hansel put out a knuckle-bone, and the old woman, whose eyes were dim, could not see, and thought it was his finger, and she was astonished that he did not get fat.”

The previous 1900 edition also has incredible inked illustrations, such as this thirteenth witch for “Briar Rose”…

…or this one, still from Hansel and Gretel.

“Stupid goose!’ cried the Witch. ‘The opening is big enough; you can see that I could get into it myself.”

Talking about briar roses, there’s also a “beautiful” illustration to the rather gruesome tale of Sweetheart Roland, in which the witch dances herself to death in a briar hedge (a similar scene is the traditional ending of the tale we know as Snow White).

The quicker he played, the higher she had to jump.

Of this theme too there is an inked version from 1918 within the English Fairy Tales, that I was unable to find at a better resolution than the one I propose you down here.

1913. Mother Goose

In 1913, Mother Goose: The Old Nursery Rhymes by Charles Perrault were collected into a book, after having been published individually in the US monthly magazine St. Nicholas. You can see original edition on sale here, for instance. Mother Goose herself is rather witchy to begin with. It was on auction here in September 2017 and it was sold for $ 20.000.

Among these fairy-tales, we also find a Nursery Rhyme, old enough to feature in printing since 1714, and then in 1744 within Tommy Thumb’s Pretty Song Book.

There was an old woman lived under the hill,

And if she’s not gone she lives there still.

Baked apples she sold, and cranberry pies,

And she’s the old woman that never told lies.

Rackham’s old woman, though not literarily a witch, is depicted with the usual gear of a pointy hat and a cat, albeit striped and not black.

1917. A Wayside Chat

I don’t know where this illustration comes from, nor if it’s supposed to be the illustration of some story, but if you like it, it’s on auction here.

1917. Little Brother and Little Sister (and other tales)

Going back to proper books, this is another collection of fairy-tales from the Brothers Grimm, whose title is one of the tales: the tale is also known as “Ninnillo e Nennella” in in Giambattista Basile‘s Pentamerone, and as “Sister Alionushka, Brother Ivanushka” in Russia, where it’s tremendously popular and was collected by by Alexander Afanasyev in his Narodnye russkie skazki. The witch in question is a wicked stepmother, and the two siblings run away, but the witch charms the forest. There’s transformations, a deer with a golden chain around his neck, a sister who forgets all about his brother, and a “happy ending” where the witch is burned at the stake, her other daughter is torn to pieces by wild animals, the dead queen comes back to life and everyone lives happily ever after.

One edition of the collection is on sale here, with some nice pictures of the inside which helped me identifying the tales of some of these illustrations. There’s also another one here, less helpful.

This “witch and the maiden” is a subject on which Rackham returned a few times: you can see a watercolour from 1916 here.

1918. Some British Ballads

Another collection of legends and poetry, mostly based on The English and Scottish Popular Ballads by Francis James Child. You can buy it here also in digital form, and includes coloured illustrations to 15 stories:

- “Clerk Colvill“, a ballad also included in Ballads Weird and Wonderful (1912) with illustrations by Vernon Hill;

- “Young Bekie“, also known as “Young Beichan” or “Lord Bateman”, in which a Londoner is taken prisoner by various characters and has troubles keeping his promise to marry his lady rescuer;

- “The Gardener“, where a guy tries to undress a lady and receives a fitting answer;

- “The Twa Corbies”, the Scottish version of “The Three Ravens“, with a darker twist, firstly published in by Walter Scott in his Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1812) with the aid of John Leyden;

- “Erlinton“, where a guy locks up his daughter to keep her from sinning and the plan doesn’t go too well;

- “May Colven”, also known as “May Colvin”, the Scottish variant of the “Lady Isabel and the Elf-Knight” trope;

- “Get up and bar the door“, which is basically the medieval Scottish version of “The War of the Roses, where no one between husband and wife wants to bar the door and things go South;

- “Johnnie of Cockerslee”;

- “Younge Andrew“, where our title guy seduces a girl named Helen, robs her of everything, breaks her heart and kills her, and is eventually eaten by a wolf in the woods (Merry Christmas);

- “Lord Randall“, a dialogue between the title guy and his mother, in which we gradually discover that out guy has been to visit his lover and our lassie has poisoned him by feeding him eels;

- “The Duke of Gordon’s Daughter“, where Lady Jean, the title-mentioned daughter, runs away with a guy and this guy is almost executed, eventually demoted, becomes poor, the wife leaves him, he inherits a fortune and gets the wife back (it’s even more poetic when you think that these are supposed to be children’s ballads);

- “The False Lover Won Back“, an equally questionable tale in which a man leaves a maid to go and win a fairer maiden, she chases him across three towns and eventually bribes him back with gifts;

- “Earl Mar’s Daughter“, where a girl lures a beautiful bird into a golden cage, only to find out it’s a charmed prince;

- “Hynd Horn”, also known as “Hind Horn“, a classic story of the princess not recognising the lover;

- “The Gypsy Laddie”, also known as “The Raggle Taggle Gypsy“, in which a lady runs away with the Gypses.

The best witchy character is from this last tale.

1919. Cinderella

In a similarly surprising way, Arthur Rackham takes on the subject of the Fairy Godmother giving her all the usual attributes of a less-than-benign witch, both in his revolutionary and visionary silhouettes and in the coloured illustrations he would later do in 1933.

1920. Irish Fairy-Tales

“Morgan’s Frenzy”.

“They offered a cow for each leg of her cow, but she would not accept that offer unless Fiachna went bail for the payment.”

1922. English Fairy Tales

In 1922, Rackham worked on the illustrations for English Fairy Tales, retold by Flora Annie Steel (you can flicker through it here). This gave him a chance to give us a witch and a tree, again, for the tale “The Two Sisters”.

“Tree of mine! O tree of mine! Have you seen my naughty little maid?”

1928. The Legend of Sleepy Hollow

Arthur Rackham worked at an illustrated edition of this famous work by Washington Irving in 1928, for an edition you can find here. This below is a recolouring of the original work done in black and white, something that – as we know – Rackham liked to do a lot. You can see another witch-like figure in this illustration under Major André’s tree, and another one riding on a skeleton horse across a stream, leading imps and other demonic creatures in her run. Since Rackham kicked some serious asses when it came to drawing creepy trees, and since the story mostly revolves around creepy trees, I really suggest you check it out.

Witches gatherings were a theme that Rackham found interesting, obviously: he took the chance to illustrate one for Sleepy Hollow, even if there actually isn’t such a scene in the book, and he also did in this illustration.

1936. Peer Gynt

Rackham illustrated Peer Gynt by Henrik Ibsen in 1936 for a George G. Harrap edition, with 12 colour plates and almost 40 inkworks you can see published here. The dust jacket, which rarely gets reproduced, is equally glorious and you can see it here. Among these illustrations, there’s a scene in which our hero meets a couple of troll-witches, also featuring in the famous incidental music In the Hall of the Mountain King by Edvard Grieg.

The troll-courtiers:

Slay him! The Christian man’s son has seduced

the fairest maid of the Mountain King!

Slay him! Slay him!A troll-imp:

May I hack him on the fingers?

Another troll-imp:

May I tug him by the hair?A troll-maiden:

Hu, hey, let me bite him in the haunches!A troll-witch with a ladle:

Shall he be boiled into broth and bree to me.

Another troll-witch with a butcher knife:

Shall he roast on a spit or be browned in a stewpan?

Unfortunately, lots of Rackham’s illustrations are drowned in generic posts about Halloween and websites for the purchase of reproductions, so it can be really difficult to find the sources for these illustrations. With this one below I failed.

No Comments