I hope you guys are not expecting to have a story each hour for the whole night, because that’s not going to happen.

Still, the Arab Dance dance was one of my favourite pieces when I was a child, I was a bit of an orientalist, so I felt bad to close the night without the beautiful dancing goldfishes. They are the fourth piece of the suite in Fantasia and they come after the Sugar Plum Fairies, the Chinese Mushrooms and the Russian thistles.

3. The Nutcracker Piece by Piece (4)

As it was for the Chinese Dance, the idea of including an Arab Dance comes within the scenes where people from all around the world are paying homage to Clara and the Prince and bearing gifts: the Chinese arrived bearing tea, the Arabs arrive bearing coffee.

3.4. Arab Dance: the music

Ass odd as it might sound, coffee has a good relationship with classical music (well, it’s not going to seem that odd if you know the musicians I do). One of the earliest works is Schweigt stille, plaudert nicht (Be still, stop blabbering, or something like that), also known as The Coffee Cantata, composed by Johann Sebastian Bach in his late years, probably between 1732 and 1735. It’s a comic opera talking about coffee addiction and I can’t believe I didn’t know about this before. Bach directed a musical ensemble based at Zimmermann’s coffee house and he might have seen some stuff: the work was probably performed at a coffee house in Leipzig and it makes fun of moralists in Germany, who regarded coffee as a drug addiction. They were not wrong, but Bach won. Words were written by Christian Friedrich Henrici, known as Picander, a German poet who worded for many of the cantatas written by Bach in Leipzig.

Regardless of coffee, orientalism inspired by a fairy-tale idea of the middle-east is spread throughout classical music, especially under the Turkish label. This kind of style was particularly frequent in Austria, due to the historical connections between the two Countries, and the most famous musician to adopt this is probably Mozart: his Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Serraglio) is the epitome of this style, featuring instruments like bass drum, cymbals, triangle, and piccolo to evoke “Turkish” atmospheres. He also used these kind of tunes in his Piano Sonata in A, K. 331 (1783) and in the finale of the Violin Concerto No. 5 in A major K. 219 (1775), called “Turkish concerto”.

Only his contemporary Joseph Haydn is equally significant, in this sense: his L’incontro improvviso (1775) resembles a lot Mozart’s Abduction from the Serraglio, and is considered a prominent example of the Austrian fascination with orientalism. It features Persia, pirates and sultans.

Beethoven also worked around the same subjects: his most famous work is the Turkish march, originally born as incidental music to a play by August von Kotzebue called The Ruins of Athens (1812). This piece was highly influential: Franz Liszt wrote a piano transcription called “Capriccio alla turca sur des motifs de Beethoven” (1846) and a version for orchestra and piano titled “Fantasie über Motiven aus Beethovens Ruinen von Athen” (1837); Anton Rubinstein arranged a piano version in 1917; Sergei Rachmaninoff furtherly worked on Rubinstein’s version in 1928.

In general, each time you have a Sarabande, chances are you’re looking at an orientalist work: the Sarabande is a Spanish dance in triple metre with heavy Arab influences, that was banned for being indecent and was revived by the same composers and in the same periods we have seen so far: Bach used it even outside the traditional use of baroque period (the Sarabande was usually the third of four movements in the dance suites of the time), for instance as the most famous of his Goldberg Variations.

The sarabande was revived in the 19th and early 20th centuries by the German composer Louis Spohr (in his Salonstücke, Op. 135 of 1847), Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg (in his Holberg Suite of 1884), French composers such as Debussy and Satie, and in England, in different styles, Vaughan Williams (in Job: A Masque for Dancing), Benjamin Britten (in the Simple Symphony), Herbert Howells (in Six Pieces for Organ: Saraband for the Morning of Easter), and Carlos Chávez in the ballet La hija de Cólquide.

Themes like Salomé and Sherazade were also particularly popular, in classical music, following the “translation” of One Thousand and One Nights by Edward Lane, John Payne and Sir Richard Francis Burton.

Oscar Wilde wrote a beautiful play on Salomè in 1893 (you might have seen the stunning illustrations by Aubrey Beardsley), upon which Richard Strauss based an opera which shocked the audience with its Dance of the Seven Veils. Later works include a French Opera by Antoine Mariotte (1908) and a ballet by Florent Schmitt (1907).

On Scheherazade, the most famous works are by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, who wrote an opera Scheherazade 1888, and Maurice Ravel, who wrote a set of three pieces for voice and orchestra Shéhérazade in 1902. There’s also a lot of Aladdin-themed stuff, but this would be a tale for another cartoon.

The Peacock Skirt is without any doubt the most famous illustration by Aubrey Beardsley to Oscar Wilde‘s play.

In light of this, if Tchaikovsky’s Chinese Dance received criticisms for perpetrating a racist stereotype only in the latest period, the Arab dance started being criticized a lot earlier, not only because it was racist (as if somebody cares) but because it was slightly sexualized in a ballet supposedly for children (and that’s something some people will care about a lot more than racism).

The dance has a slow tempo, secretive and seductive, and unsurprisingly was thought as a seven veils dance.

The most famous and interesting modern rendition is probably the one featuring Sergey Chumakov and Elena Petrichenko for the Moscow Ballet.

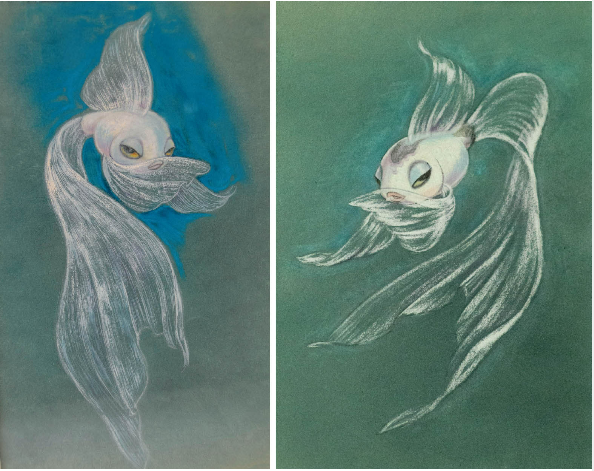

3.4. Arab Dance: Fantasia’s goldfishes

The sequence, almost explicitly a harem with female goldfishes seductively twirling in bubbly water, was animated by Donald “Don” Lusk, who had also worked on Ferdinand the Bull (1938). Knowing what we know about the animators at Disney, it’s unsurprising that a guy who worked on the story of a bull who likes flower and doesn’t want to fight was picked to work on such a delicate sequence, where some of his colleagues might probably have been not at ease to do so.

Among the artists involved, The Walt Disney Archives chooses to show us a small pastel from young Faith Rookus, but I wasn’t able to find any information about her and her work if not on the footnote of one of the They Drew as They Pleased volumes, admitting that little is known about her. You can see a picture of her here, alongside other ladies working at the studios, and she’s also briefly featured in the book Ink & Paint: The Women of Walt Disney Animation, published in 2017. There’s also some records of work from Milton Quon, one of the first Chinese Americans to be employed as animator at Disney’s, who recently died at the respected age of 105. Yes. A hundred and five.

The exotic lead Arabian fish had a double, Joyce Coles of the Belcher School of Dancing according to some sources, an actual Arabian dancer according to others. In any case, a real dancer was brought in the studios to pose with the choreography of the appropriate dance.

Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston wrote: “Never has an object on celluloid looked so diaphanous and delicate”. They were right.

Disney had dabbled with orientalist dances before: the 1931 Silly Symphony Egyptian Melodies, for instance, featured wall paintings coming to life to entertain (and scare off) a wandering little spider. The segment, as many segments of that period, was directed by Wilfred Jackson, who had also worked on Steamboat Willie and will direct A Night on Bald Mountain in Fantasia, and music was written by Frank Churchill, who will write at Disney some of the most popular tunes ever including music for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

On the other hand, Disney seems to have a thing for dancing fishes, way before The Little Mermaid. Their first structured attempt has to be the Silly Symphony Frolicking Fish, a black and white short from 1930 still distributed by Columbia Pictures and directed by Burt Gillett, in which the party of a group of fishes is disturbed by an evil octopus until an anchor from above puts an end to his villainy.

An undersea exhibition that keeps the patrons chuckling all the way. All sorts of fantastic fish are put through a dizzy series of dances, drills and whatnot, in tune to some unusually fitting music. The chief amusement is provided by a villainous octopus chasing a fish, but the wicked one is given the k.o. in the end when the smart little fish drops an anchor on him from a sunken vessel. One of the best in the Silly Symphonies series. The Film Daily (September 28, 1930)

The soft-shoe dance was animated by Norm Ferguson and Walt Disney was particularly impressed by his work. He will also work on Fantasia, mostly animating characters for the Dance of the Hours.

Another Silly Symphony featuring dancing fishes is King Neptune (1932), this time in colour, although fishes are a support role for mermaids and Neptune, who punishes a bunch of pirates for harassing his girls. The story has amazing artwork, for the time, and apparently it was also made into a pop-up card or something. It was directed by Burt Gillett, who worked on a huge amount of Silly Symphonies and is particularly known for his 1933 Three Little Pigs, with music by Bert Lewis (the musician of Steamboat Willie).

There’s also some dancing fishes in the trippy Silly Symphony Merbabies (1938), directed by Rudolf Ising and Vernon Stallings, who will also work on Fantasia. In this piece, not dissimilar to the previous and equally tripping Water Babies (1935), authors Jonathan Caldwell, Pinto Colvig and Maurice Day takes us through the carefree days of some half-fish/half-octopuses half-babies living underwater in the sea. They parade around, they play a concerto and they marvel at the grace of mergirls (but, as I said, Disney’s thing with mermaids will have to wait for another piece of writing).

Regardless of the occasional goldfish in a bowl which might perform the occasional dance (like Mickey Mouse’s traditional goldfish Bianca or Geppetto’s goldfish Cleo), the only other significant dancing fishes are seen in Bedknobs and Broomsticks, a wildly underrated movie starring Angela Lansbury as a British amateur country-witch and Disney star David Tomlinson as his unwilling charlatan mentor. In one of the many mixed-technique features, the main characters fall in the lagoon of an enchanted island and they dance with fishes at the tune of The Beautiful Briny, written by the same Sherman Brothers who brought Mary Poppins’ tunes to life. The song is actually recycled from Mary Poppins: supposed to be used for a compass sequence that was scraped.

It’s lovely, bobbing along

Bobbing along on the bottom of the beautiful briny sea

What if the octopus

The flounder and the cod

Think we’re rather odd

It’s fun to promenade

Bobbing along, singing a song

On the bottom of the beautiful briny sea

To be fair, after Fantasia we’ll we also see some dancing fishes in Alice in Wonderland (1951), specifically in The Walrus and the Carpenter sequence, but they’re mostly dancing ashore (except for oysters, which are not fish and that really doesn’t count).

In recent times, Disney also made another go at orientalism, this time with a more respectful and carefully researched approach, in the tv series Mickey Mouse (starting in 2013), where Disney’s main character is portrayed with different habits and living in different places all around the world: driving a scooter in Paris to deliver baguettes for Minnie’s café (season 1, Croissant de Triomphe), driving a cab in India (season 2, Mumbai Madness), attending a Russian ballet in Moscow (season 3, Dancevidanya). We visit Middle-East in episode 51, season 3, where Mickey is selling Turkish Delights at a bazar. The episode is a trip of acid and a delight for the eyes.

There were also two Chinese-based episodes, with dialogues completely in Chinese, that I forgot to mention in my mushroom pieces: Year of the Dog, taking place in Shanghai, and Panda-monium, set in Beijing Zoo.

The short also features a very Turkish version of Goofy, trying to sell musical instruments next to Mickey’s stall.

3.4. Fairy-tale fishes

As usual, let’s close the article doing a round on fishes as fairy-tale characters: Norse mythology reeks with them (see the King of Fishes in The Three Princesses of Whiteland, my next Sunday-time Norse folk-tale) and I would never finish should I have to deal with fishes in Chinese mythology. Luckily enough, we’re talking about an Arab dance in a Russian ballet, so let’s take a look at how fishes are represented in more exotic tales, for a change.

The first tale that comes to mind is the Russian The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish, a fairy tale in verse written around 1835 by the Romantic playwright and novelist Alexander Pushkin. As it often happens in these kind of tales, a fisherman manages to catch a wonderful Golden Fish and the creatures which promises him to fulfil any wish, in exchange for its freedom. The tale is similar to the Brother Grimm’s tale The Fisherman and His Wife, and they both revolve around greed, tricksters and wishes going badly.

In the Russian version, the fisherman initially wants for nothing, and lets the creature go, but his wife gets angry and sends him back to ask for a new trough. Seeing that the fish is granting the request, the wife prompts him to ask for bigger and bigger gifts, starting from a house and reaching the point where she requires to be made the Ruler of the Sea, in order to subjugate the golden fish completely to her boundless will. The sea gets angrier and angrier at each request, until the Golden Fish reverts every wish he has granted and brings the fisherman’s wife back to her poor state, including the broken trough. In 1866, the tale was adapted into a ballet called Le Poisson doré with music by Ludwig Minkus and choreography by Arthur Saint-Léon. It is also an opera by Nikolai Tcherepnin (1917) and in 1950 was animated by Mikhail Tsekhanovsky. The tale is highly popular and was beautifully illustrated several times. My favourite illustrations are probably the ones by Ivan Bilibine and Valery Carrick .

The German fairy-tale that supposedly was inspirational, The Fisherman and His Wife, carries out similar concepts: a poor fisherman lives with his wife in a hovel on the shore and manages, one day, to catch a sentient fish. The charmed creature, which claims to be an enchanted prince, grants him a wish and the man wants for nothing, but the wife insists that he goes back and asks for a house. Wish after wish, the sea gets more turbid and muddy: the wife prompts him to ask for grander and grander things, until she requires to be made equal to God, and to command the sun, moon, and heavens. As it happens in the Russian version, the fish reverts everything and the wife finds herself stripped of all previous gifts.

The tale was collected through a manuscript given to the brothers by German painter Philipp Otto Runge. Johann Gustav Büsching had already published another version of the same manuscript in 1812 in his Volkssagen, Märchen und Legenden, and this had scholars quarrelling over the original version for ages. The tale features in Virginia Woolf‘s To the Lighthouse, in which Mrs. Ramsey is reading the story to her son. There have also been different retellings of the same tale, after Pushkin’s version.

As it often happens with Grimm’s fairy-tales, there are illustrations to spare. Robert Anning Bell did some beautiful work, such as the title I give you below. He’s particularly famous for his painting The Pool, but you might also want to check out his A flight of fairies. He illustrated Grimm’s Household Tales in a translation by Marian Edwardes.

The Fisherman’s Wife is a trope in folk tales (with its own Aarne-Thompson type nr. 555) and has lots of versions. Another one, also collected by the Brothers Grimms, is called The Gold Children and, instead of relying on greed, the protagonists’ undoing of fortune relies on the ability to keep a secret which, as you know, it’s not people’s strong suit in fairy-tales. In this complicated story, the fisherman catches the fish three times and for three times he gains a castle, but for three times he is unable to keep the secret with his wife and looses everything. The third time, obviously bored of being fished out of the water over and over again, the fish tells him to take it home and cut it into six pieces: he is to give two to his wife and two to his horse, and to bury the last two pieces in the ground. The wife gives birth to twins of gold, the mare gives birth to two foals of gold, and two golden lilies sprout from the earth. And then they grow up, they leave the house, they meet a witch and lots of other stuff happens.

The role of the golden fish in these kind of tales is called donor, which Vladimir Propp lists as one of the seven roles in fairy-tales: they are often found in liminal areas between realms, such as the woods and the seashore.

Fishes also appears as “consultants” in stories such as the Norse folk-tale The Three Princess of Whiteland (again) or Farmer Weathersky, in which our hero consults first all the animals and then all the fishes, which are usually unable to help and send him to birds (or vice versa, depending on the information the hero is looking for). On a side note, if you read the plot of Farmer Weathersky you’ll find similarities with the transformation lessons of The Sword in The Stone.

An illustration by Lancelot Speed in The Red Fairybook: the sister of the sea calls all fishes (but nobody knows anything)

A fish also features as a helper in Thumbelina, a literary fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen, in which our little hero is helped by a friendly butterfly and a friendly goldfish (an illustration to the scene can be found here).

On a side, note, the most famous association between women and goldfishes has to be Gustav Klimt‘s, with his Blood of Fish (1898), his super-creepy Nymphs also dubbed Silver Fish (1899), the two Water Serpents (both between 1904 and 1907) and most importantly his Gold Fish (1901).

No Comments