Before Christmas, I wrote something about Kay Nielsen and in that piece I mentioned an old Disney Project that never was: the famed Musicana, a sort of new version of Fantasia that would have had music from around the world. It was a beautiful project and you can read all about it here. Some of you reacted enthusiastically to that mention, so I decided to continue this winter tales series and to bring you some behind the scenes, less known art and abandoned projects revolving around Disney’s Fantasia. They are probably going to sue me and close my blog, so you better print out all those Dynamo tutorials.

Some of these stories, regarding the Nutcracker, came out during the night between December 23rd and the 24th, a night in which traditionally women in my region used to stay up and tell each other stories. I continue with the series.

Essential Bibliography

If you like this kind of things, there’s a bunch of books you simply can’t ignore.

The first is certainly The Walt Disney Archives, a book so big it comes in his own suitcase. It’s pricey, bot worth every penny: 620 pages of stories, sketches and pictures. You have an extensive description of it on the editor’s website (of course it’s a Taschen book).

Each of the major animated features that were made during Walt’s lifetime—including Pinocchio, Fantasia, Dumbo, Bambi, Cinderella, Peter Pan, Lady and the Tramp, and One Hundred and One Dalmatians—are given their own focus chapter, without forgetting less familiar gems such as the experimental short films of the Silly Symphonies series and underappreciated episodic musical films such as Make Mine Music and Melody Time, all of which receive the same meticulous research and attention.

Many unfinished projects, among them the proposed sequels to the legendary musical Fantasia or a homage to Davy Crockett by painter Thomas Hart Benton, are also highlighted with rarely seen artworks, many of them previously unpublished. Throughout, contributions from leading Disney specialists detail the evolution of each respective film.

The second necessary reference is the They Drew as They Pleased series, which instead of focusing monographically on movies takes into consideration the life and work of significant artists, writers, illustrators and other personalities who worked at Walt Disney Studios across the different eras. Some of them are also available in digital format, others can be purchased only in paperback. The complete list, as far as I know, consists of these books:

- Disney’s Golden Age: The 1930s, with many unproduced projects as well as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Pinocchio, and some early work for later features such as Alice in Wonderland and Peter Pan;

- Disney’s Musical Years (The 1940s – Part One), with incredible works of musical experimentation and innovation;

- Disney’s Late Golden Age: The 1940s, in which Fantasia gets the lion’s share;

- Disney’s Mid-Century Era: The 1950s and 1960s, featuring Cinderella, Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan, and Sleeping Beauty;

- Disney’s Early Renaissance: the 1970’s and 1980’s, with works like The Jungle Book, The Aristocats, Robin Hood, and The Rescuers;

- Disney’s New Golden Age: The 1990s to 2020, with work from beloved new classics like Aladdin, The Lion King and Pocahontas.

Another necessary book is The Disney That Never Was: The Stories and Art of Five Decades of Unproduced Animation, by Charles Solomon (of which you have a very nice review here) and, by the same author, Disney Lost and Found: Exploring the Hidden Artwork from Never-Produced Animation.

Director Woolie Reitherman. In the background are storyboards by Mel Shaw for the abandoned project Musicana (Didier Ghez. They Drew as They Pleased Vol 5, Courtesy: Bruce Reitherman)

0. Original Selection

The original idea for the movie included loads and loads of stuff, stuff such as:

- Moto Perpetuo by Niccolò Paganini, which was to be a pseudo-demonic celebration of industrialization;

- Troika, a piano adaptation of November from Tchaikovsky‘s Seasons by Sergei Rachmaninoff;

- Prelude in G minor, also by Sergei Rachmaninoff;

- The Song of the Flea, a piano composition by Modest Mussorgsky with lyrics taken from Goethe‘s Faust;

- Babes in Toyland, and particularly the famous March of the Toys, from the operetta by Victor Herbert, a Christmas-themed musical extravaganza featuring toys and fairy-tale characters that would have its own Disney live-action movie in 1961;

- Don Quixote, a project Disney tried to bring on screen many times, as you can read here, and that ultimately caused the break-up between the studios and Argentinian artist Eduardo Solá Franco;

- Midsummer Night’s Dream, although I’m unclear whether the idea was to put Shakespeare’s tale to music or to use Felix Mendelssohn‘s famous theme to accompany some other tale;

- beloved tale Brementown Musicians, for which Igor Stravinsky was apparently offering to write an original score;

- Maurice Ravel‘s Bolero, that oddly enough will be used in an Italian homage to Fantasia by Bruno Bozzetto called Allegro non troppo after the classical music tempo (but with the literally meaning of “merry, but not so much” because all pieces are fucking sad);

- a March of the Little Lead Soldiers by Gabriel Pierné;

- the Grand Canyon Suite by Ferde Grofé, which would eventually be used in 1958 as the soundtrack of the short movie Grand Canyon;

- The Ring of the Nibelung and particularly the Ride of the Valkyries, on which Kay Nielsen himself will work long after the financial flop of Fantasia;

- the Dance Macabre by French composer Camille Saint-Saëns.

Of all the segments, the selected ones eventually included:

- Toccata and Fugue in D minor by Johann Sebastian Bach;

- Cydalise et le Chèvre-pied by the same Gabriel Pierné of the Little Lead Soldiers, a ballet featuring a satyr in love with a ballerina and, as we’ll see in a minute, the piece was supposed to include a lot of other stuff;

- The Nutcracker Suite by Pyotr Tchaikovsky, a selection of pieces from his adaptation of E.T. Hoffmann‘s The Nutcracker and the Mouse King;

- Night on Bald Mountain by Modest Mussorgsky paired with Franz Schubert‘s Ave Maria;

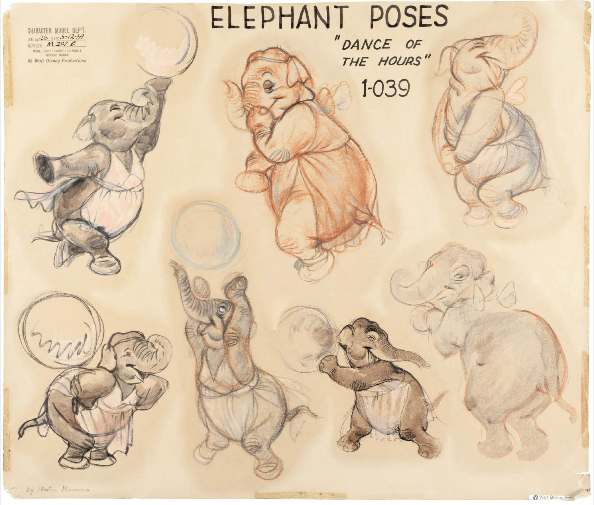

- the Dance of the Hours, the final ballet in Amilcare Ponchielli‘s opera La Gioconda;

- Clair de Lune, the third movement of the Suite bergamasque in Claude Debussy‘s piano suite inspired by Paul Verlaine;

- The Rite of Spring ballet by Igor Stravinsky;

- The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, a symphonic poem by French composer Paul Dukas and based on a poem by Goethe.

Clair de Lune was scraped from the production, due to budget and timing, and the satyr piece will become what be paired with music from Beethoven‘s Pastoral Symphony. And how this came to happen is, in my opinion, the first story worth telling.

1. The Pastoral Symphony

When I was a kid I had a huge passion for this piece. There were flying horses, my little ponies, beautiful goddesses and a drunken unicorn: what was there not to like? The music is slightly altered in length by Leopold Stokowski, the direction of the piece was assigned to Hamilton Luske (supervising animator of no other than Snow White in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs), Jim Handley and Ford Beebe. Story development was in the hands of Otto Englander (who also worked on Snow White), Webb Smith (usually recognised as the inventor of storyboards as we know them), Erdman Penner, Joseph Sabo, Bill Peet (a children’s book illustrator, story writer and animator who worked on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and stayed in the studios for nearly 30 years, until early in development of The Jungle Book, until he quarrelled with Walt himself and broke off) and George “Vernon” Stallings. Character design by James Bodrero, John P. Miller and Lorna S. Soderstrom: two of them we’ll have the chance to talk about, but unfortunately there’s very little information around the work of Lorna, the only prominent woman credited in the staff of Fantasia.

Other staff included:

- Art direction: Hugh Hennesy, Kenneth Anderson (mostly famous for his work on One Hundred and One Dalmatians), J. Gordon Legg, Herbert Ryman (a crucial artist in the development of the Disneyland concept), Yale Gracey (also special effect designer behind Pirates of the Caribbeans in Disneyland), and Lance Nolley (also known for writing Paul Bunyan);

- Background painting: Claude “the Gentle Giant” Coats, Ray Huffine (who also did the backgrounds for Lambert the Sheepish Lion), W. Richard Anthony, Arthur Riley, Gerald Nevius, and Roy Forkum;

- Animation supervision: Fred Moore (particularly known for his habit of drawing nude girls that occasionally made their way into Disney movies, like the Lolita centaurette), Ward Kimball (specialized in shorts, who eventually also worked on the movie Babes in Toyland), Eric Cleon Larson (one of Disney’s Nine Old Men), Arthur Harold “Art” Babbitt (father of Goofy, a giant of animation, who fell from grace after the Disney animators’ strike in 1941), Ollie Johnston (a giant, who co-authored the milestone book Disney Animation: The Illusion of Life, with the 12 basic principles of animation), and Don Towsley (who would eventually become main animator for Donald Duck);

- Animation: Berny Wolf (who also worked on Pinocchio and Dumbo), Jack Campbell, Jack Bradbury, James Moore, Milt “the Duck Man” Neil, Bill Justice, John Elliotte, Walt Kelly (who would later father Pogo), Don Lusk (who started working at Walt Disney Studios aged 20 and then moved to Hanna-Barbera studio), Lynn Karp (also part of the famous Disney animators’ strike), Murray McClellan, Robert W. Youngquist, and Harry Hamsel.

The symphony has 5 movements and the cartoon follows these movements in showing us a story of everyday life on Mount Olympus:

- Movement I: Introduction (Allegro ma non-troppo);

- Movement II: Love is in the Air (Andante molto mosso);

- Movement III: The Grape Harvest (Allegro);

- Movement IV: The Thunderstorm (Allegro);

- Movement V: Reconciliation (Allegretto).

I’m no musical expert: if you want to dive into some musical aspects of Disney, I suggest you check out this Youtube channel, which helped me figuring out the division of the piece.

1.1. Introducing you…

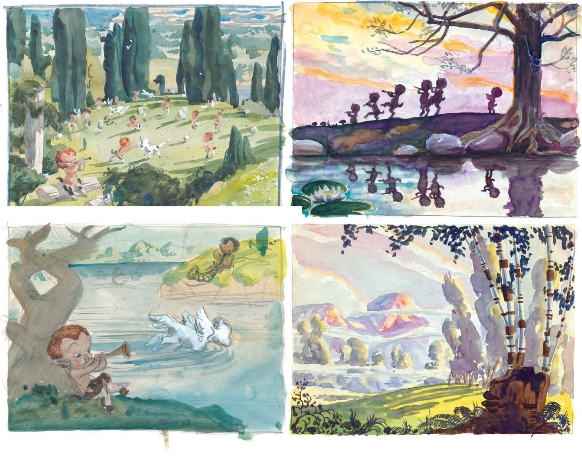

Mel Shaw was one of the two artists featuring in Volume 5 of They Drew as They Pleased and he has also worked on the adaptations of one of my favourite British novels, The Wind in the Willows (his work would be poured into the mix of The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr Toad). His first assignment, however, was in February 1938, when he was called to work on pieces for this new strange thing that was going to be called Fantasia. His pieces were supposed to include suggestions from the ballet Cydalise et le Chèvre-pied, and in particular with music from one of the most recognizable pieces, L’École des Ægipans, also known as The Entry of the Little Fauns or The March of the Fauns. It would also include suggestions from Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, by Claude Debussy, and a sudden intrusion on the notes of Flight of the Bumblebee by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov.

The whole thing was removed from the program late in the writing process and was ultimately replaced with sections from Ludwig van Beethoven‘s Pastoral Symphony, but lots of the preliminary work was not thrown away.

The Flight of the Bumblebee segment was the first to catch the artist attention, even before it was even revealed the idea of working on something called Fantasia, as the artist himself explains in 1989 in a letter to animation historian Michael Barrier.

“When I made my storyboard for the ‘Flight of the Bumblebee’ I did it in full color (watercolor). At that time there was no Fantasia. It was a classic music short. After my 1st meeting with Walt we discussed the possibilities of doing a full concert program including this subject as one segment . . . ”

As he stated again in 1994 when interviewed by Paul F. Anderson:

The droning cadence of “The Flight of the Bumblebee” was usually performed as a violin instrumental and suggested the rapid fluttering of a bee moving from flower to flower. I developed a sleepy mythical faun whose nap was repeatedly interrupted by an intrusive bee collecting pollen from the faun’s bed of wildflowers.

The piece was an orchestral interlude written by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov for his opera The Tale of Tsar Saltan and till today it remains one of the most popular pieces he ever written, because of the vibrant and chaotic way it’s composed and the clear picture it evokes. The piece in fact closes Act III of the opera, where the magic Swan of the tale changes Prince Gvidon Saltanovich into a mosquito so that he can fly to visit his father the Tsar and tell him that he is alive. There’s an operatic overture to the piece, sang by the Swan, which is usually omitted and has little ties to the musical piece itself.

Well, now, my bumblebee, go on a spree,

catch up with the ship on the sea,

go down secretly,

get deep into a crack.

Good luck, Gvidon, fly,

only do not stay long!

The whole opera is based on a poem by Aleksandr Pushkin (1831) and originally illustrated by Ivan Bilibin, who would also work on sceneries and costumes for Rimsky-Korsakov himself. Its themes are classified 707, as they feature dancing water, a singing apple and a speaking bird, but it’s generally considered a fairy-tale in verse. The complete title goes along the line of The Tale of Tsar Saltan, of His Son the Renowned and Mighty Bogatyr Prince Gvidon Saltanovich, and of the Beautiful Princess-Swan. Yes. I know.

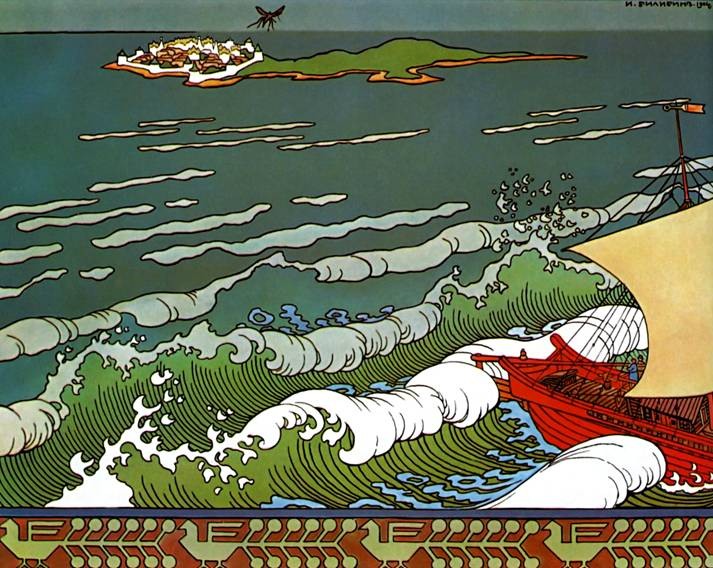

Ivan Bilibin illustration to the original scene, where the prince is transformed into a mosquito. I hate insects in general, but there’s no arguing that a bumblebee is better.

The piece was to be ripped from its original concept and to be integrated with the other pieces where satyrs and fauns were the main subject.

The idea was to use an earlier version of surround sound in order to give the illusion that the bumblebee was flying around in the theatre.

Apparently, Mel Shaw’s storyboard produced a bit of a revolution in Walt Disney’s office too.

Most storyboards at this time were done in black and white but I decided to do my “Flight of the Bumblebee” presentation storyboard with pencil and watercolor. I felt that this would bring out the brilliant colors of the flowers and trees and help everyone visualize my idea for the setting of the story. A few weeks later Dave Hand and Walt came to see my work and when Walt paused in front of my colorful storyboards for a moment, he suddenly let out a big “WOW!” From his reaction I thought that this must have been the first color storyboard ever presented to Walt.

It would later be included in Melody Time in the jazz arrangement Bumble Boogie by Freddy Martin.

Anyway, this was only supposed to be a digression in the whole piece featuring fauns: Cydalise et le Chèvre-pied, the ballet giving the working title to the segment, tells a different story. The young satyr Styrax is playing pranks in the Gardens of Versailles, disturbing dryads and nymphs who eventually decide to tie him up to a tree, in spite of nymph Mnésilla, who tries to plea for him because she secretly loves him. When he is finally able to get free, he crosses path with a group of artists who are coming to represent in front of King Louis XIV a comedy-ballet called La Sultane des Indes: amongst them, the beautiful first ballerina Cydalise. The faun falls in love at first sight and decides to follow the artists hidden in a trunk. He manages to seduce her and receives a rose in gift, they dance together and eventually dawn separates them, but not before the faun puts her to sleep with a branch of poppies and gives her a kiss. The fucking creep.

Some of the concepts for fauns and satyrs made by Mel, as you can clearly see, didn’t go unused. Unfortunately, by the time Fantasia came out he was already working on something else.

According to The Walt Disney Archives, the deco style of the sceneries in this piece was specifically set by art directors Ken Anderson and J. Gordon Legg. Even if I’ll spend a little more words on the symbolistic flavour of the scenery in this piece, it’s worth spending a couple more words about inspirations and contaminations for this piece, before we proceed.

Anderson was an architect: he graduated at Washington and grew up under the influence of Lionel Pries, who also was the Director of the Art Institute of Seattle and did fairy-tale-like projects such as the Waterfront Mansion and Hood Canal district featured in this article. Anderson worked at Walt Disney Studios for 44 years, on pretty much anything, and if we consider only Art Direction he signed Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Pinocchio, the cartoon sequences in The Reluctant Dragon, the cartoon parts of Song of the South, the short Ben and Me, One Hundred and One Dalmatians, The Sword in the Stone. He also had the chance to work as an architect for the Haunted Mansion in Disneyland, and we can try and trace back to him some of the architectural accuracy for the romantic ruins used in the Pastoral sequence.

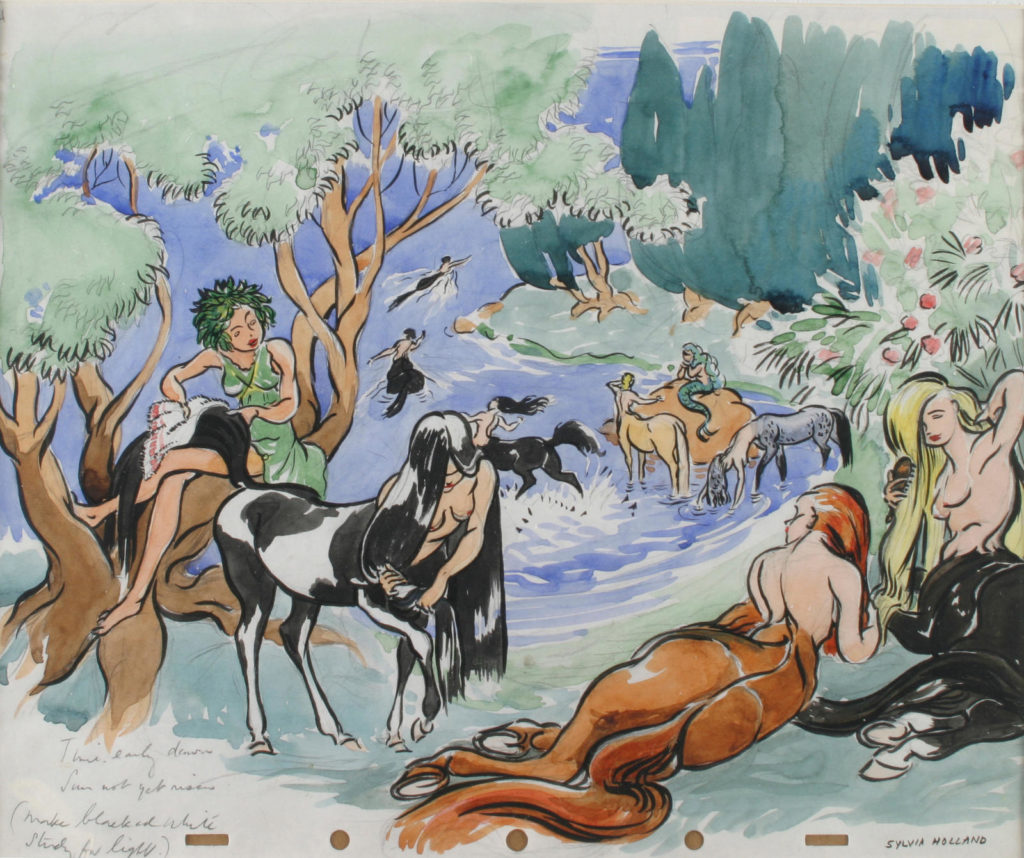

Sylvia Holland was the first woman to join the Royal Institute of British Architects and the second woman to be hired ad Disney not as a colourist. She also authored this concept sketch. I’m on love with the raven-haired centauress in the middle.

When it comes to romantic and deco influences, one of the artists involved, Robert Cormack, payed a direct homage to one of my favourite painters, John William Waterhouse. I can’t show you his watercolour, which features in the gorgeous book The Walt Disney Archives, but I can show some of the Waterhouse painting it refers to: the waterlilies and bathing nymphs seem to come from Hylas and the Nymphs, but the same motif also recurs in Lamia, Echo and Narcissus, and several of the Nymphs Finding the Head of Orpheus.

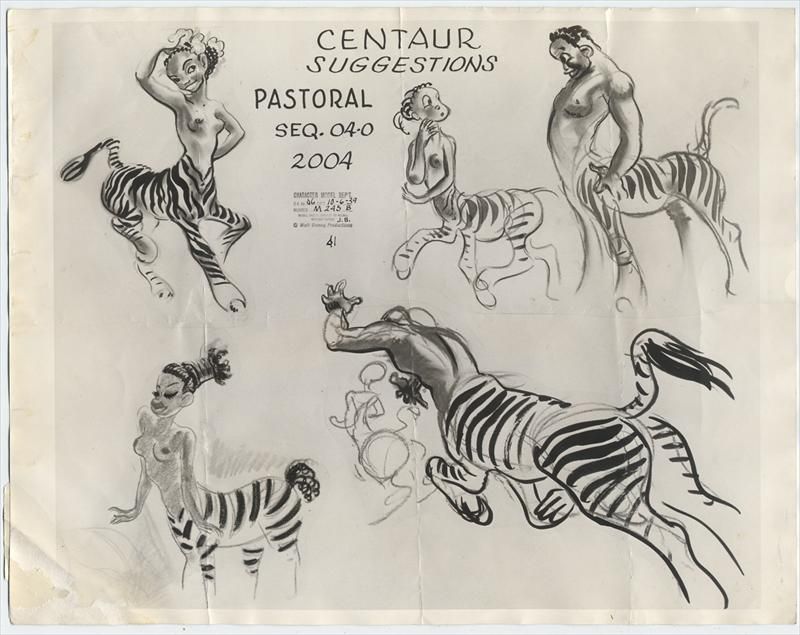

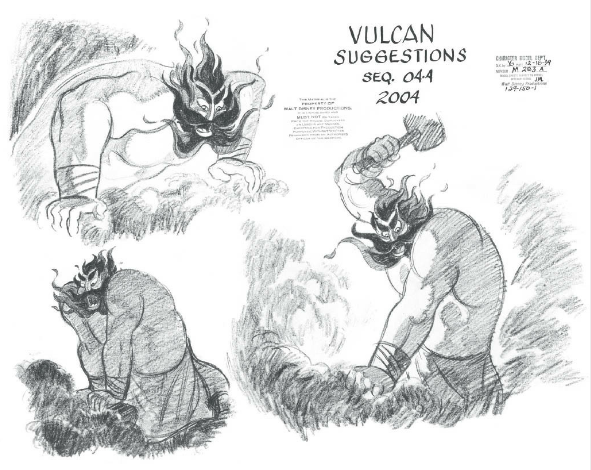

The second artist working on the Pastoral’s satyrs, as far as I could dig up, was Jack Miller, one of the three founding members of the Character Model Department at Walt Disney Studios by 1937. Dubbed “the ultimate character designer”, he produced detailed sheets of how the characters should look like and worked on within the Pastoral he worked on fauns, Zeus and Vulcan.

There is a storybook quality to Miller’s character models that is reminiscent of the most elaborate drawings by Ernest Shepard, the illustrator of Winnie the Pooh and Wind in the Willows.

– Didier Ghez, They Drew as They Pleased (Volume 5)

The third one just has to be James Bodrero, who has a special place in my heart because he also worked a lot in Wind in the Willows (but that has to be the story for another time).

He was a highly creative Belgian artist (half of the artists at Walt Disney Studios were immigrants: food for thought, in these troubling times) and he was involved in the movie by Leopold Stokowski himself, as he would narrate to Milton Gray during an interview in 1977.

At least a year after that, Stoky said to me, “What are you doing at present, Jimmy?” I said, “Nothing in particular… Why?” He said, “Why don’t you come to work at Disney’s?” I said, “For Christ’s sake, Stokowski, do you see me making ducks’ feet move?” Stoky said, “Listen, if it’s good enough for Deems Taylor and it’s good enough for me, it’s good enough for you. There’s something going on there that isn’t making ducks’ feet move.” That was the first I ever heard of Fantasia. He said, “You’ve got to come down and see what’s going on down there.”

Indeed he had to.

The first project he started working on was the Dance of the Hours, but he soon started working parallelly also on unicorns, with fellow genius Martin Provensen, along with centaurettes and Bacchus.

But where are these fauns coming from? I have zero ideas around what was the actual inspiration for Bodrero, Miller and Shaw, but I can tell you what they remind me of.

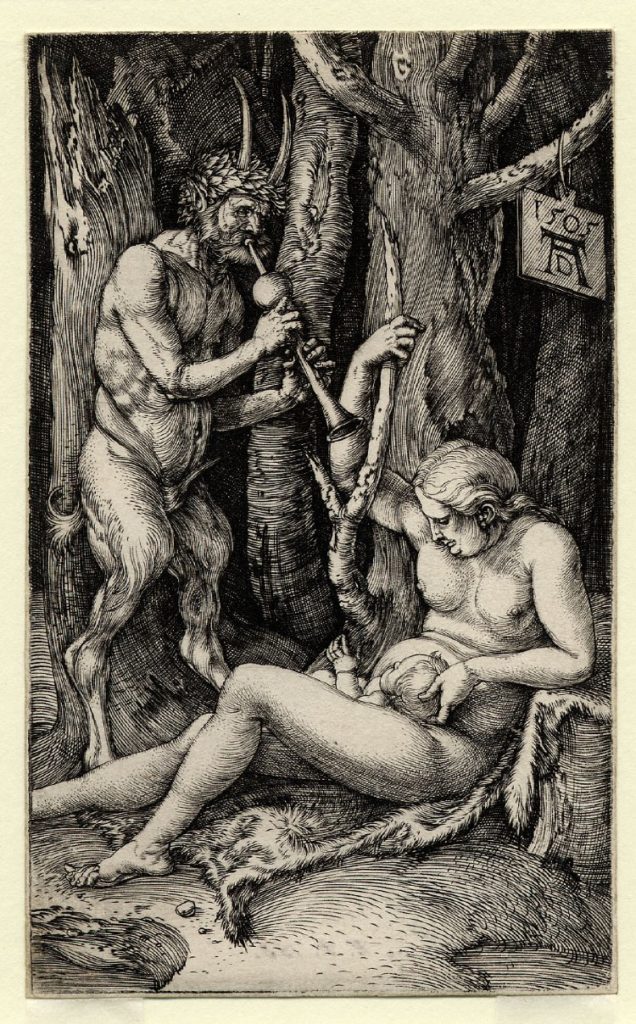

If you take a look at theBarberini Faun or if you simply take your time to browse fauns, satyrs and their chief Pan in iconography, you’ll see that up until a certain point they inevitably are represented as bearded ugly things, running at the tail of nymphs. The idea that there might be child-like creatures among them doesn’t appear until Late Renaissance. The most famous representation of a domestic satyr is Albrecht Dürer‘s 1505 engraving The Satyr’s Family, below, where the child however is not showing any goat-like features or, if he is, we just can’t see them. The same went for earlier illustrations of the same genre, where the faun was generally used to convey the concept of the good savage, as it happens in Lucas Cranach the Elder’s depiction of a “faun” with his family.

There doesn’t seem to be a significant representation of a faun with child-like features until the early XX Century, when all of a sudden they start pouring in. Stunning English painter Isobel Lilian Gloag portrays a playful Mænad and Fauns somewhere between 1902 and 1912, the incredible German symbolist Franz Stuck gives us a young faun with a creepy smile also in 1902, Ludwig Knaus stays somewhere in between the playful and he obscene with his Faun and Goat (1829 – 1910).

Since these kids cannot be seen chasing nymphs without arising a certain discomfort in the bourgeoisie viewer, they are often portrayed playing pranks or playing the Pan Flute. This is the case for a whole array of youngsters portrayed in a whole variety of moods, from Johann Ferdinand Apollonius Makart’s exceedingly merry faun (1870) to Stanisław Bohusz-Siestrzeńcewicz s melancholic Little Faun (1923).

If you want something really creepy, I suggest you check out this Art in the Manor by Jacek Malczewski. If you want something from someone famous, you might want to check Franz von Stuck‘s Old Faun.

Anyway, what really matters here is that somewhere between the XIX and the XX Century, fauns stopped being old creeps and started being (also) young pranksters. Pretty much around the same time, they also entered children’s literature and, consequently, they became suitable subjects for illustrators. In this, a significant role might have been played by J.M. Barrie and his Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, particularly since it was illustrated by Arthur Rackham. Even if Peter is fully human and his only connection with the god Pan is in the name, Rackham’s iconic illustration of the child playing the flute left a deep mark in popular imagination. His work is unparalleled.

There are other artists, however, who started drawing fauns with a similar style and who might have been inspirational for what the guys at Disney were trying to do. In this, Henry Gerbault is certainly one. The works I’m thinking about are a series of illustrations for commercials I wasn’t able to find anywhere else but here. You have your Scottish hunter selling a faun child door to door, a rare idea for a female faun carrying a child as an example of motherly pride, wingless fauns fluttering around charming ladies in their undergarments, a lady in her stockings holding a faun child, and below a faun o’clock illustration.

There’s also some astonishing graphics done for advertisements in Italy, by Ottorino Andreini.

You can find other beautiful concepts here.

1.2. Centaurs, centaurettes and cupids

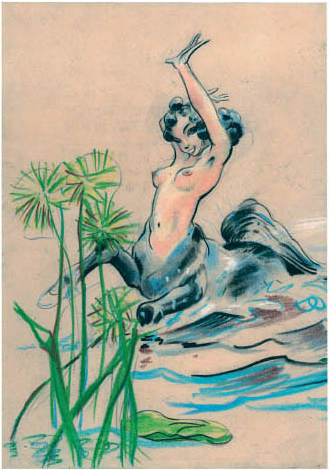

Well, if the idea of child-like fauns was not so weird anymore back in those days, and Fantasia certainly contributed in affirming it, the idea of centaurettes was significantly older but no less unusual, and among all the artists who worked on them I just have to pick James Bodrero. He had an expertise in depicting horses and this was one of the most significant reasons he was picked for the job, alongside his colleague and friend Martin Provensen, although in all due honesty it might also have been because the guy owned an actual donkey, something not so frequent in Santa Barbara, California. The little guy was a a Sicilian donkey, named Bomba, on which the artist had also written a book.

The work they did was a more romantic and non-interracial twist on the classical story of centaurs storming into a party to steal women, main subject of the famous Centauromachies, in which the centaurs attempt to kidnap Hippodamia and the rest of the Lapith women on the day of her marriage to Pirithous, king of the Lapithae and, according to certain versions, cousins to the centaurs themselves. This generally leads to the assumption that, just as much as it happens for dwarves, there are no women among the centaurs. This is not the case. Female versions of centaurs, sometimes called Centaurides or Centauresses, are occasionally mentioned in literature. The most famous of them is Hylonome, wife of the centaur Cyllarus, who kills herself after loosing her husband during the war with the Lapiths. she’s mentioned by Ovid in his Metamorphoses.

In the high woods there was none comelier of all the centaur-girls, and she alone by love and love’s sweet words and winning ways held Cyllarus, yes, and the care she took to look her best (so far as that may be with limbs like that). She combed her glossy hair, and twined her curls in turn with rosemary or violets or roses, and sometimes she wore a pure white lily. Twice a day she bathed her face in the clear brook that fell from Pagasae’s high forest, twice she plunged her body in its flow, nor would she wear on her left side and shoulder any skin but what became her from best-chosen beasts.

They are heavily featured in both Roman and Greek art: you have them in mosaics, for instance, where art has been more preserved, like Villa Adriana and Pompeii’s Dionysos House, or this one in Roman Tunisi, where two centauresses are parading Venus like we’ll see two very particular centaurettes are doing with Dionysus in Fantasia.

Philostratus the Elder (or Philostratus of Athens, we aren’t really sure) describes these in his Imagines, an invaluable work in which the author describes artworks that are lost to us. His description sounds a lot like what we see in Disney’s Fantasia.

How beautiful the Centaurides are, even where they are horses; for some grow out of white mares, others are attached to chestnut mares, and the coats of others are dappled, but they glisten like those of horses that are well cared for. There is also a white female Centaur that grows out of a black mare, and the very opposition of the colours helps to produce the united beauty of the whole.

On a side note, I laughed really hard in reading the story of the Lamberts, a British family which – accordingly to Arthur Fox-Davies‘ A Complete Guide to Heraldry – wanted to use a female centaur holding a rose in her left hand in their family crest, but they were unable to establish these arms officially, and in the XVIII century had to change them to a male centaur holding a bow. A significant story.

Anyway, as I was saying, people at Disney seem to be taking almost literally Philostratus’ description and we have a wide variety of what they call centauresses. Alongside James Bodrero, characters were developed by John P. Miller and Lorna S. Soderstrom, and were originally depicted bare-breasted, at least until artists were forced to cover them up the Motion Picture Production Code because ‘oh my god, nipples’.

Apparently nipples were more troubling than slavery, back in 1940 (and I would argue that it still is the case): bare-breasted centaurettes were censored, but what was originally depicted as a celebration of diversity turned into a coat of different paints all over bodies and faces of creatures modelled with caucasian features. With the notable exception of one character, animated by Milt Neil and usually referred to as “Sunflower“, whom you might or might not know about. She’s a funny little creature, with a solar disposition, the caricatural features of an African girl that were typical in lots of satirical cartoons of the time, and she’s clearly very happy to be serving the other centaurettes, prepping them for their beaus’ arrival. The character made it in theatres and was censored in 1969. You can see the censored scenes in some YouTube videos like this one. She also has a twin, equally censored, named Otika, who rolls the carpet for Bacchus in the next segment.

Racists depictions at Disney are unsurprising and they have been very common for decades. This is not particularly surprising, if you consider that – regardless of the obvious multicultural environment that was already characterizing the studios – the first person of colour to work as an animator at Disney was hired only in the 1950s. His name is Floyd Norman and in this interview he also provides an insight on how to read these kind of scenes.

“There just wasn’t the same sensitivity there as we have today,” he says. “A lot of this happened, it’s unfortunate, but that was just the times in which we lived. I don’t think we should go back and try to erase the past. This was part of our history, this is part of what happened, and so we should be able to deal with that.”

I don’t think it’s for me to agree nor disagree with him.

Regardless of Sunflower specifically, I remember that as a kid I had always found odd that the blue centaurs were paired with the blue centaurettes, the yellow with the yellow, the red with the red, as if there was no choice. I guess cartoons are not good nor bad, if you have a brain and if you received the basis of a decent education. But this is a concept out of fashion, nowadays.

Anyway, if you’re into these kind of Centaurs, in 1921 there also was an animated feature called The Centaurs, by Winsor McCay, produced by Rialto. The movie is unfortunately lost, with the notable exception of a production film of around 90 seconds you can find on different channels like the one I include below.

The surviving footage presents a young female centaur picking flowers, a male centaur throwing a rock at (and, perhaps, killing) an eagle in flight, a pair of elderly centaurs (the male is bald with a long white beard, the female wears pince-nez eyeglasses) welcoming the younger centaurs, and a bald boy centaur who jumps around. Since no screenplay of the film is known to exist, it is not clear how these scenes were meant to be connected.

Winsor McCay was an American cartoonist, also going under the pseudonym of Silas for contractual reasons. He self-financed and animated ten films, including the famous and innovative The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918). He had tried unsuccessfully to find work at Disney Studios around the 40s and had no official contact with the work that was done there. He was however recognised as one of the fathers of animation in Disney’s “The Story of Animated Drawing”, a special produced in 1955.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hoVHhIoyoO4

Alongside centaurs and centaurettes, movement II also features prominent actions by a swarm of match-making cupids and their depiction is nothing significant: Eros himself starts off as a slender winged young man but during the Hellenistic period he increasingly becomes younger and chubbier. The little bastards are usually called “amorini”.

If you’re into sculpture, there’s also a very famous female centaur by Auguste Rodin.

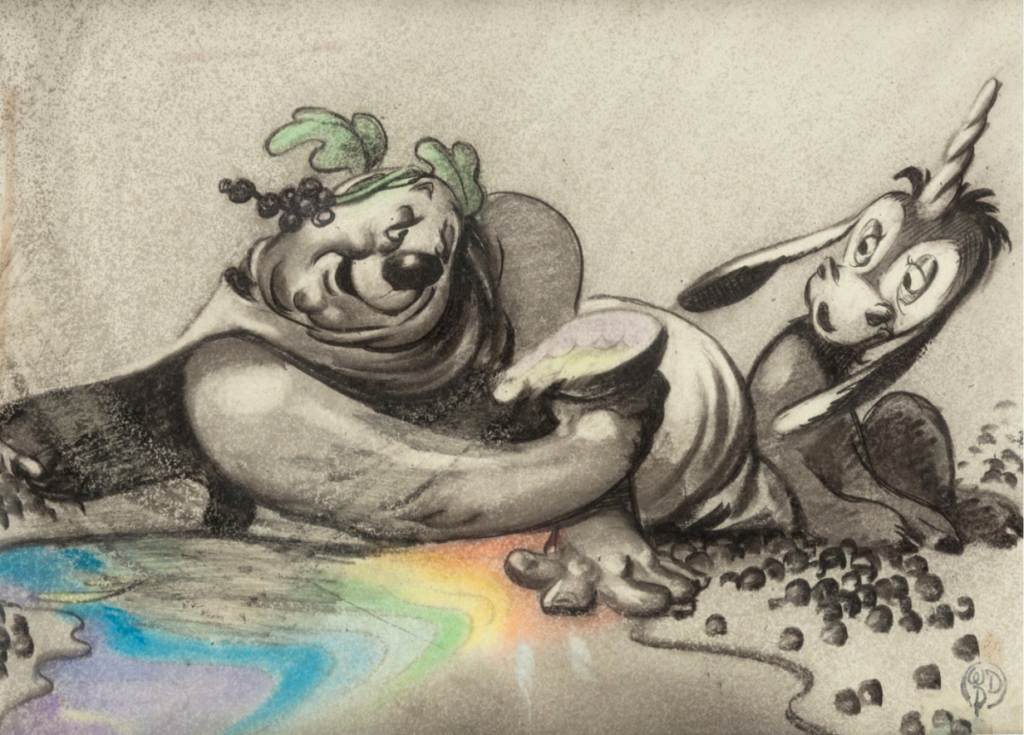

1.3. Bacchus and Grape Harvesting

After the romantic interlude in which centaurs and centaurettes all find their love (except for poor Sunflower, but unfortunately none of the visiting centaurs was rich enough to bring a slave with him), the scene changes to a bunch of significantly happier and more inebriated centaurs, centaurettes and fauns, all dancing around for a grape harvesting.

The main character of this scene is Bacchus/Dyonisus or, I should probably say, his unicorn donkey. The allusion is of course to the Bacchanalia, but with a little less sex and a lot less cannibalism (alleged). It is undoubtedly the comic relief, after all that time spent in romantic anguish and serenity.

Martin Provensen worked a lot on the concept, with his pal James Bodrero whom, as you might remember, was picked for the job (also) because he owned a donkey. The first result is the

Otika, whom I already mentioned, is Sunflower’s twins in rolling out the carpet for Bacchus, and it’s the only censorship in this piece. Oddly enough, she’s not the only character that is somehow racist, because also two other servants for Bacchus are depicted as women of colour, half women and half zebras. They were probably not erased because their depiction is not caricatural (so I guess it’s ok to show people of colour just as servants but at least do not make fun of them?). The final result is aesthetically beautiful and they were one of my favourite characters as a kid. It’s interesting to see that in the original concept they too were entitled to have their mates. Scraped, of course. You can find additional material here, including a 3d model for the character.

The ‘Nubian’ centaurettes in a character sheet from Fantasia. I’m not sure whether it’s signed by one of the character designers.

The working name of Bacchus pal, the unicorn donkey, apparently is Jacchus and you just have to love him. You can see Bodrero’s style in drawing him, especially if you compare him to what happens to young mischievous Lampwick in Pinocchio during his transformation into a donkey.

The donkey is a beloved figure in Greek and Roman mythology, everyone knows Apuleio’s donkey, but what you might not know is that the idea of a figure related to Bacchus is not original: Silenus, the companion and tutor of young Dionysus in Greek mythology, was often portrayed riding a donkey, just as it happens on these coins or on this mosaic, and the donkey was one of his symbols.

The idea of the unicorn is also not an invention from the Middle-Ages, as is sometimes believed, and is mentioned by Greek and Roman natural historians such as Ctesias the Cnidian, Strabo, Pliny the Younger, Aelian and Cosmas Indicopleustes. Particularly Ctesias, in his book Indika written while he was living in current Persia, described unicorns as wild donkeys with a 70 cm horn painted in white, red and black. Antigonus of Carystus follows him and writes about the one-horned “Indian ass” in his Historiae Mirabiles, “Collection of Wonderful Tales”. You might say that the original unicorns were donkeys and the slender horse-like creatures we know today are imposters. This would make Jacchus one of the most historically-accurate depictions in Fantasia, though you might not have said that by looking at him.

1.4. The Thunderstorm

Just because you can never have fun without someone storming in to ruin the party, the fourth sequence is the one in which we start to see other deities, before the grand finale, and particularly we meet a hyper-greek Zeus and his blacksmith Vulcan.

If you remember Didier Ghez’s note on Miller’s work, there was a reference to his characters being somehow as sophisticated as the one of Ernest Shepard, and I promised I would return on it. Here’s me returning on it.

Ernest Shepard had been the illustrator for The Wind in the Willows and Winnie-the-Pooh, and was particularly influencing at Disney because of his anthropomorphic animals and his way of bringing toys to life in both those works. His illustrations are, however, much more than that and this is why I’m bring him up while talking about deities in Fantasia. Take a look at his Neptune in the propaganda illustration below.

If possible, the style artists pick for Zeus in Fantasia is even more statuary, especially in the way they decided to chisel his beard. The style has heavy symbolistic influences (take a look at architectural decorations like this). Depictions of Serapis are usually closer to what Fantasia’s Zeus looks like. The two-bearded Jupiter is something that’s slightly more frequent in Tarots like the Swiss deck, there his figure is used instead of Arcan V, the Hierophant.

In his thunderstorm and in his tormenting Dionysus, Zeus is briefly aided by Aeolus, keeper of winds, although his representation is so similar to Zeus that you are left with the doubt. The character is officially referred as Boreas, and also makes a brief appearance in the live-action/animated film So Dear to My Heart.

The third main character of the segment is an underdressed Vulcan, and I would swear it’s kind of dangerous to roam around in a forge in your undergarments. He is portrayed as limping, as traditionally in Roman and Greek mythology, and in the first depictions he had a Mephistopheles look around him, that progressively softened until he became something closer to (another) comic relief.

In general, the whole segment is one of Disney’s favourite thing to put on the screen, probably because lots of classical music had been trying to capture a thunderstorm into notes.

The oldest cartoon with this subject since the Silly Symphonies times and one of my favourites is probably The Old Mill, a 1937 Silly Symphony directed by Wilfred Jackson, scored by Leigh Harline, where a storm hits an old mill and the surrounding area, threatening and affecting the animals living nearby. The techniques experimented in the segment would later be used in the nightmare sequence of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Previously, a similar experiment in black and white had only been conducted in Springtime (1929), which incidentally is the same short that scares the puppies while they’re watching tv in One Hundred and One Dalmatians.

The Old Mill is available for streaming on Disney+, while the others aren’t available yet.

1.5. Reconciliation

In the last segment, the storm ceases and the Sun shines again, just in time to bid farewell with his chariot and for a peaceful Night to fall on the Countryside. This segment has the most crowded scenery, starting from the goddess of rainbow Iris and ending with Artemis shooting the night sky full of arrows using the crescent moon as a bow.

This is by far the most heroic segment: no comic relief, aside from a brief scene with Dionysus toasting to Iris and baby Pegasus playing with Cupids. The Hellenistic natural scenery is here appreciated mostly, with the most peaceful sceneries echoing closely what will be the short segment Trees in Melody Time (1948).

Surrealism and Symbolism are among my favourite art movements. Should you want to check some Olympian-related art from early XX Century, there’s a lot of stuff out there, stuff you rarely see. One of my favourite painters is Alphonse Osbert, a melancholic French guy who was inspired by Jusepe de Ribera and specialized in muses. Alongside the famous Isle of Kites (below), you might also want to check the Rêverie en la Nuit, and the Songs of the Night (also below).

Talking about symbolism and Hellenistic sceneries, you are probably expecting me to mention the Swiss painter Arnold Böcklin, so I might as well do that. The work you probably have in mind is his Isle of the Dead, but there’s also a far less known Isle of Life and The Elysian Fields. There’s also a homage to this artist, by Ferdinand Keller, whom in 1901 paints Böcklin’s grave in a style he might have liked. He also did an Island of Dead, with a far more abstract twist.

Going back to muses and Mount Olympus, Maurice Denis brings us some beautiful sceneries both in his Nabis and in his symbolist period: his Gioco del Volano (1900) and his Elisarion almost seem part of the same cycle, but the last most striking examples of this kind of art are probably to be recognised in Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, the last French painter of the so-called School of Lyon: he studied under Eugène Delacroix, Henri Scheffer and then Thomas Couture, and gave us stuff like Young Girls by the Seaside (you surely know it), Fantasy featuring a Pegasus, and the slightly unsettling The Dream. He also did a beautiful Sacred Wood, but it was lost in a fire. If we ever get to talking about the Ave Maria segment in Fantasia, we’ll have to go back to some of these guys.

Another artist worth checking out is Belgian painter Jean Delville: significantly more interested in girls than in Hellenistic architecture, he gave us incredible stuff like The Angel of Splendor, and The Love of Souls.

In spite of a contrary appearance, all the forces, all the manifestations of nature influence each other with currents of negative polarity and positive polarity, undeniable astral influences. … The great contrasts of life, however, are responsible for all the misery, all the hardship; are they responsible for the production of Chaos? A huge mistake: The Great and the Small, the Strong and the Weak, the High and the Low, the Active and the Passive, the Full and the Empty, the Weighty and the Dense, Exterior and Interior, the Visible and the Invisible, the Beautiful and the Ugly, the Good and the Bad, Essence and Substance, Spirit and Matter are divergent forces which eternally constitute the great Equilibrium in the Universal Order. It is a Natural Law, and no philosophy, no dogma, no doctrine will ever prevail over It.

I live with one of my favourite painters, an Italian one: Gaetano Previati. He is a divisionist, a style I’m not overly fond of, but his depiction of both light and darkness, especially when he decides to work with both of them at the same time, is simply incredible. He moved very young to Milan, my city, and studied under Giuseppe Bertini, Giovanni Morelli, and Federico Faruffini. His Dance of the Hours is simply incredible, Armonia owned by Gabriele D’Annunzio is as beautiful as you might expect from something owned by Gabriele D’Annunzio (it’s the one in the header of this post), but Daylight waking up the Night is astonishing. I guarantee that the original is even more beautiful. There’s also a Chariot of the Sun, and is really worth looking for it.

No Comments