Well, Christmas came and went, my Advent Calendar is at an end, I’m endeavoured in the Twelve Days of Christmas and I did some bonus pieces on Disney’s Fantasia, but that doesn’t mean I’ll leave you without your weekly ration of Norse folk tales.

The tale I bring you today is The Three Princesses of Whiteland, part of East of the Sun, West of the Moon and also collected by Andrew Lang in his Red Fairy Book.

1. The Story

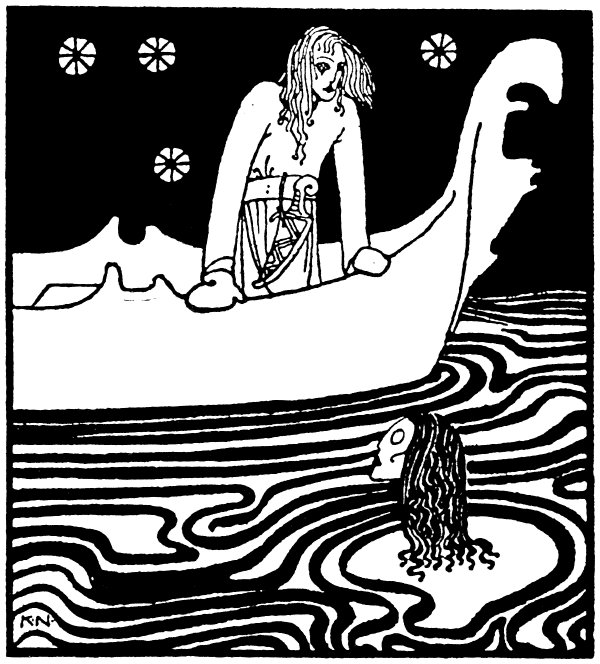

A fisherman was going fishing, one day, but he couldn’t seem to manage to get much our of it. When the evening approached, a head popped up from the water and offered him a bargain: the head proposed to give him fish in trade for whatever his wife carried under her girdle, and he said yes. Of course, he returned home all merry and happy with his food, only to find out that his wife is pregnant and he just offered his baby to a floating head. Desperate, he lamented his misfortune and the king came to hear his story. He took pity on the child to be and he offered to raise and protect him. And so he did.

So it came to be that the boy grew up at the King’s Castle. Knowing why he was there and the story of how he came to be, still one day he begged to go with his father fishing, because growing up in a castle probably doesn’t mean that you’ll also grow up a smart kid. As soon as he set foot in the boat, he is dragged off to a far away land.

On those strange shores, he meets an old man and from him he hears that he has arrived to Whiteland and that if he walks down the shore he’ll meet three princesses buried up to their necks in sand. Apparently, it’s a thing that if you talk to the third, the youngest, it will bring you good luck. Because who would ever think of trying to free them?

So he does, and the youngest princess tells him that they are in that predicament because three trolls had imprisoned them there, and that he can free them if he goes up to their castle let each troll beat him for one night straight. A flask of ointment by the bed will cure all his injuries in the morning and a sword would let him cut off their heads. Only then, the princesses would be free.

The first troll has three heads and three rods, and as soon as the hero gets his beating and kills him, the princesses find themselves standing in the sand up to their waists. The second has six heads and beats him with six rods, but when the hero defeats him the princesses are standing in sand up to their knees. The third is of course the most challenging, with nine heads and nine rods, and beats our hero so badly he cannot reach for no ointment nor sword, but the troll has the bad idea of throwing our hero against a wall, the flask breaks, our hero heals and he then kills the troll, freeing the princesses.

He marries the youngest and lives happily with her for several years, but eventually he grows homesick and asks for a way to go back home and visit his parents (the fishermen, not the king and queen, because at this point he already married a princess and we don’t care about the people who actually raised him anymore). His wife finally agrees and gives him a magic ring that will grant him two wishes, one to go home and the other to return, but he warns him that he musts do only what his father asks, and not what his mother wishes. And we all know how good men are to resist what their mothers tell them.

Unfortunately, his mother wants to show him to the king (a nice sentiment, if you ask me) and while he’s at court he gets this urge to summon his wife and compare her to the king’s wife (which is a fucking weird thing to think, if you consider that the queen is the woman who raised him). He then uses his second wish to summon his wife and of course she gets upset. She takes the ring from him, she knots in his hair a ring with her name on it (something similar to what the youngest princess does to the soldier in The Three Princesses in the Blue Mountain) and wishes herself home again.

From now on, the tale is a classical search for the lost wife. Our foolish hero tries to reach Whiteland on his own and, in his attempt, he reaches the King of All Beasts. Unfortunately, the king of all beasts doesn’t have a clue as to Whiteland is, but he lends our hero a pair of snowshoes and advises him to go asking his brother, the King of All Birds. Unfortunately, the king of all beasts doesn’t have a clue either and lends our hero another pair of snowshoes (they must break awfully quick or it must be one hell of a snow) and sends him to his third brother, the King of All Fishes.

In a plot twist, this king doesn’t know either but an old pike finally arrives at court and tells our hero that he has heard his wife is going to remarry the day afterwards and he indeed knows how to reach Whiteland.

Our hero just has to face a final challenge: he has to win a magical hat, cloak, and pair of boots, which would let the wearer make himself invisible and wish himself wherever he wanted, and he does so with the classical plot device of tricking three people that are quarrelling over the treasure. He sets to Whiteland and on his way he meets the North Wind, who – as we have already seen – is a jolly good fellow and offers to help him. They arrive at his castle, the North Wind sweeps his competitor away and he shows himself to his wife, who recognizes him by the ring in his hair. And they live happily ever after.

2. Illustrations

One of the favourite themes for illustrators, aside for Kay Nielsen, is the moment where the King of Beasts summons his subjects, probably because it’s a scene Henry Justice Ford decided to illustrate in Lang’s Red Fairy Book.

Aside from Kay Nielsen, as you have seen, in this post I also included some Russian illustrations, but unfortunately I do not know the name of the author. Help, as usual, is appreciated, though the style and colors seem to be the ones of Katherine Shtanko. Below you can find another one of the same series: the King of Fishes summoning his loyal subjects.

Theodor Kittelsen also illustrated this edition and his fishes are particularly good. You have already seen some of his work for the Princess On the Glass Hill.

As far as modern illustrators go, I suggest you check out this piece by Merle Hunt.

3.1 A Bad Bargain

The incipit recurring concept featured in this fairy-tale is the bad bargain between a human in need and a supernatural creature and it usually features someone involuntarily promising his own soon-to-be born child. Scottish tale Nix Nought Nothing is one of the most famous tales with this subject: a queen gives birth to a son while the king is away, and names him “Nothing” because she doesn’t want to christen him without the presence of his father. The king is then aided by a giant and in return the creature requires “Nothing”. You can guess how well that turns out.

This is a significant variation of the usual trope of a fairy-character requiring for the first-born in payment, as the trade is done unknowingly. The theme is also present in some variations where we don’t have to wait for the child to be born: in Estonian tale The Grateful Prince, also collected by Andrew Lang in The Violet Fairy Book, an old man offers to help the king getting out of the forest in exchange for the first thing that will greet him as soon as he gets home (he’s unhappy because think it’ll be his dog and it turns out to be his newly born son); some variants of Beauty and the Beast; The Girl Without Hands, in which a man agrees to give the Devil what is standing behind his mill only to find out he just gave away his own daughter; Polish tale King Kojata, in which a creature gets a hold of the king’s beard and doesn’t let go until he promises to give away “the most precious thing in his palace, which was not there when he left it”.

Talking about Polish people, those among you who read modern fantasy will have already spotted that the same theme is used by Andrzej Sapkowski‘s The Last Wish, the first book of his famous Witcher saga, the child-surprise. This should not surprise: all tales in this delightful first book are reinterpretations and reinventions of classical fairy-tales tropes, from Snow White and the Seven Dwarves to Sleeping Beauty, and it’s only fair that he also used something coming from a folk tale of his own Country.

Concept art for The Witcher III videogame. You can find more here, and another one is in the header of this post.

1 Comment

Pingback:Soria Moria Castle – Shelidon

Posted at 19:27h, 10 January[…] noticed, are by one Theodor Kittelsen, a beloved Norwegian artist I already talked about for fhe Three Princesses of Whiteland and for the Princess On the Glass Hill. He illustrated some editions of the Norse folk tales, […]