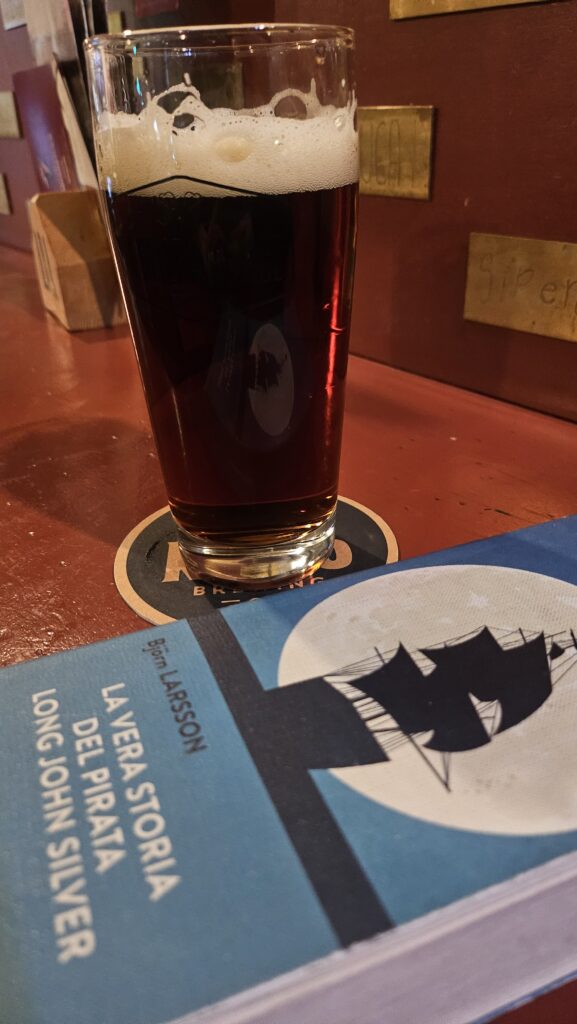

I very rarely wish I had more stars to give a book, I’m usually content within the boundaries of 1-5, but this time I did. And it’s weird because I don’t like fanfiction at all. I think it’s a cringeworthy exercise to expand on someone else’s characters. There, I said it. And possibly this is why I have delayed reading this book for so long, even if everybody I talked to kept singing its praises. I was wrong. Because this might be a piece of fanfiction but it’s a glorious one, and Stevenson isn’t the only one that’s central to this literary act of love. But let me start from the beginning.

Why Long John Silver Still Matters

I wish I had a sixth star to give this book not because it is flawless, far from it, but because it felt a necessary book. Because Long John Silver: The True and Eventful History of My Life of Liberty and Adventure as a Gentleman of Fortune and Enemy to Mankind does something that literature is increasingly afraid to do and it refuses to reassure the reader, it refuses to simplify and, above all, it refuses to make its protagonist safe, which is increasingly difficoult for at least two reasons:

- we know Long John survives, at least up to the point we meet him in Treasure Island;

- we know he’s still alive, since Larsson decides to complicate things for himself and opts for an authobiography. And if you’re talking, you’re usually still alive, as pirates like to remind us: dead men tell no tale.

Björn Larsson’s Long John Silver is not here to be redeemed, softened, or turned into a nostalgic icon, regardless of what you might have seen in reviews that didn’t understand the original character in its context: he is here to speak, to argue for himself and, in doing so, to force us to confront the fact that pirates weren’t just scoundrels to be hung and weren’t romantic saviours but, being maybe neither and maybe both, were born as acts of rebellion against power.

This is central to the book, and it’s far from being a novel notion, but more on that in a minute.

Before diving into details, let’s remember one thing: Long John Silver has always been an unsettling figure. In Treasure Island, he is neither hero nor villain in any stable sense, and that wasn’t obvious in the cultural context from which Stevenson came. He is charming, cruel, loyal, treacherous, capable of affection and ruthless calculation in the same breath. Stevenson did not accidentally create this ambiguity, and Silver is probably the novel’s most radical achievement. He embodies a world in which survival depends on intelligence, adaptability, and a constant negotiation with violence.

Larsson understands this. And instead of sanding down Silver’s edges, he sharpens them.

This is why reading complaints that Larsson “ruined” the character is not just amusing, but revealing. Those complaints usually come from a desire to preserve Silver as a theatrical villain, dangerous but ultimately harmless, frozen in a boyhood adventure story. What Larsson does instead is far more threatening: he lets Silver grow old, reflect, and speak within a historical reality that includes colonialism, slavery, economic exploitation, and systemic cruelty that goes beyond the eccentricity of some blood-soaked captain.

In this light, the pirate stops being a costume for Halloween and returns to being a political problem.

This matter now because Long John Silver represents a type of figure we are still deeply uncomfortable with: the morally compromised rebel, the person who fights an unjust system without pretending to be pure. The individual who understands that the world is violent first, and moral second, and who chooses freedom anyway. This book deserves more than a perfect rating because it dares to remind us that equality, autonomy, and dignity have often emerged not from polite reform, but from mutiny. And that the people who carried those ideas were rarely saints.

Long John Silver still matters because he forces us to ask a question we keep trying to avoid: what do we do with freedom when it comes wrapped in contradiction, blood, and uncomfortable truths?

That question has not aged a day.

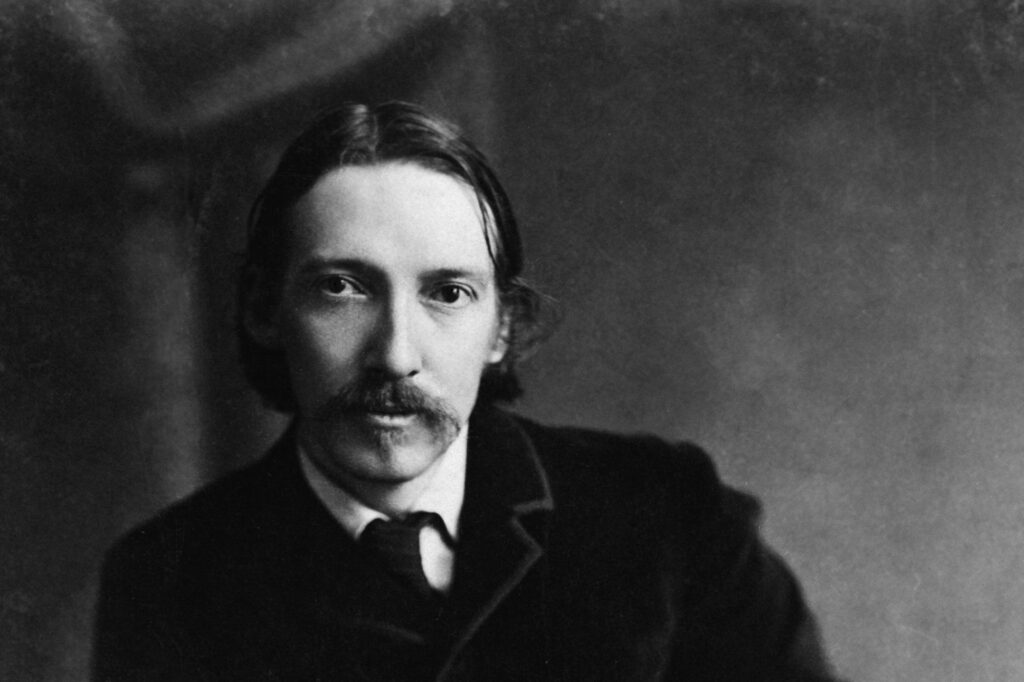

Stevenson and the Ethics of Ambiguity

The Invention of the Grey Villain

Long before Björn Larsson took up the pen, Robert Louis Stevenson had already done something revolutionary: he broke the moral contract of adventure fiction.

In Treasure Island, Long John Silver is not simply a villain in disguise, nor a fallen hero waiting to be exposed, but something far more destabilising. He is intelligent, adaptable, persuasive. He understands people, systems, and power dynamics better than almost anyone around him, including the supposedly respectable figures who oppose him. Silver survives not because he is stronger or more cunning, but because he reads the world as it is, not as it ought to be. This is what makes him radical.

Silver operates according to an ethics of ambiguity where loyalty is conditional, morality is deeply contextual, violence is neither glorified nor denied but treated as a fact of life, a currency already in circulation before the pirate ever enters the scene. In this sense, Silver does not introduce corruption into Treasure Island: he exposes the corruption that was already there, hidden beneath imperial respectability and maritime discipline.

Spoiler Alert. When Stevenson refuses to punish Silver in the way Victorian morality would demand, when he allows him to escape and carry his contradictions with him, this refusal is ideological defiance. Silver cannot be neatly classified as hero or villain because Stevenson understands that such classifications are luxuries afforded to those who benefit from stable systems of power.

What is often overlooked is that Silver is not an anomaly in Stevenson’s work.

If we move beyond Treasure Island and look at The Black Arrow (queue the musical introduction of a local show from the 60s, as far as I’m concerned), we find the Duke of Gloucester — later the infamous Richard III — portrayed as a politically astute, morally compromised operator navigating a brutal civil war and haviong to deal with the way people would look at him, a disabled man, if he wasn’t that cunning. Like Silver, he is charismatic, dangerous, and unsettling precisely because his actions make sense within the violent logic of his time. And the fact that both of them are disabled has been covered by several excellent essays (see here, for instance).

This is the throughline: Stevenson is deeply suspicious of moral purity in violent worlds. His most compelling characters are those who recognise that systems built on force cannot be resisted with innocence alone. Whether pirate or nobleman, these figures disrupt the comfortable binary between lawful authority and criminal rebellion. They reveal that legitimacy is often retrospective, granted to winners rather than earned through virtue. Seen in this light, Long John Silver is Stevenson’s most concentrated expression of a broader literary and political intuition: rebellion is rarely clean, survival demands compromise, and charisma is often more subversive than brute force. It’s Luthien’s speech all over again: you call it resistance when it’s to gain freedom for all, and rebellion when it’s just for oneself.

Larsson does not invent this Silver but inherits him through a deep understanding of these premises. Once you recognise Stevenson’s sustained fascination with morally grey, politically disruptive characters, it becomes impossible to argue that expanding Silver’s worldview — ageing him, politicising him, forcing him to confront slavery and empire — is an act of distortion. It is, instead, the logical continuation of the character. But Larsson isn’t alone in this endeavour. And if this book is a love letter to Stevenson and his character, there’s someone else who receives all the love in the world, and who’s very worthy of this love: Daniel Defoe.

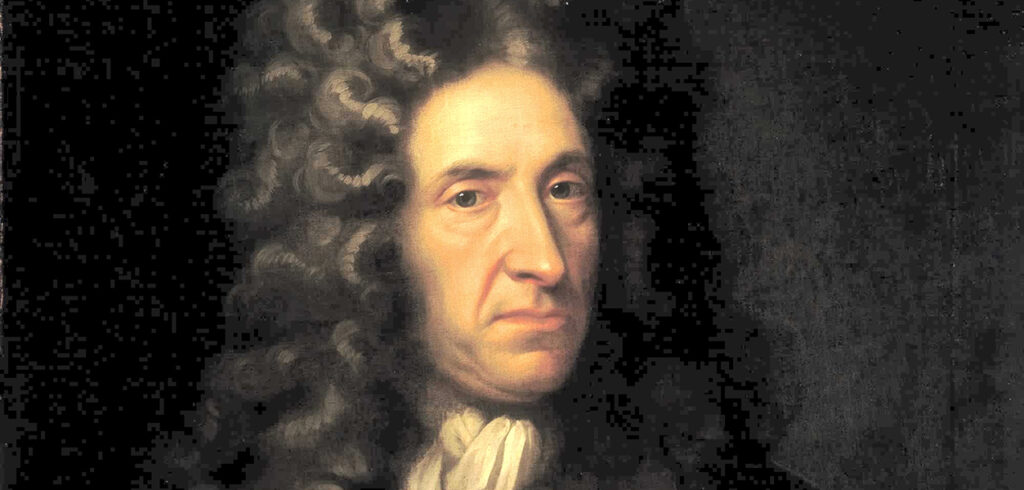

Piracy Before the Myth: Daniel Defoe and the Invention of the Modern Pirate

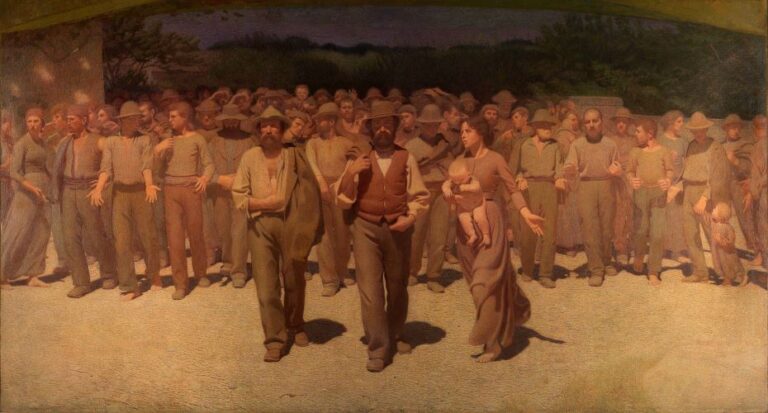

Long before parrots, flags, and romanticised lawlessness of some fiction, piracy emerged as a direct response to a world structured around extreme inequality, sanctioned violence, and systematic exploitation at sea. To understand Long John Silver not as a fantasy, but as a historically plausible figure, we need to step away from Stevenson for a moment and look at Daniel Defoe.

Born in 1660, Defoe had already tackled the portrayal of a morally ambiguous character with his Moll Flanders and had extensively been in trouble with the law, but it’s with A General History of the Pyrates (1724) that Defoe does something extraordinary for his time: he treats pirates not merely as criminals, but as social actors. Dangerous ones, certainly, but with motivations that are intelligible. He records their lives, their codes, their disputes, their internal hierarchies. He situates piracy within the economic and political machinery of early modern Europe, rather than outside of it.

This matters because Defoe is writing at a moment when maritime labour was among the most brutal forms of work available to the poor.

Sailors in the merchant and naval fleets were subjected to appalling conditions: forced enlistment, delayed or stolen wages, arbitrary punishment, starvation diets, and near-total lack of legal protection. Violence was the governing principle, discipline was enforced through terror, and authority was absolute. In this context, the moral distinction between lawful and criminal violence becomes deeply unstable. Piracy arose in response to this kind of violence. This is what makes the “modern pirate” a political problem, a figure who exposes the hypocrisy of empires that criminalise unsanctioned violence while thriving on sanctioned brutality. A worker who refuses exploitation not through reform, but through exit from the system, and arms himself in the process.

Defoe never fully endorses piracy, but he cannot dismiss it either. His pirates are often articulate, self-aware, and acutely conscious of the injustice that shaped them. They justify themselves not by claiming innocence, but by pointing out that the system they deserted was already soaked in blood: this is the intellectual soil from which Long John Silver grows. When Silver speaks of freedom, he is articulating a logic already present in Defoe’s accounts: that liberty at sea was not a philosophical ideal, but a material condition negotiated through contracts, violence, and collective agreement, something that was dangerously unthinkable in the navy. Understanding piracy as Defoe presents it — as a social and political phenomenon — forces us to abandon the comforting idea that pirates were monsters outside civilisation, and we need to face the fact that they were produced by that very same civilisation that sought to condemn them because, in rejecting it, they revealed its fault lines.

Freedom, Power, and the Question of Slavery

When Björn Larsson lets Long John Silver speak in the first person, he performs an act of historical pressure on a hero that was revolutionary at the time in ways that people might have forgotten. Therefore, Larsson does not rewrite Treasure Island nor does he correct it: he accepts Stevenson’s character as a given and then asks the only question that matters once childhood adventure is stripped away. What does this man believe, and what are the consequences of those beliefs in the real world?

Larsson’s Silver is coherent in a way that makes many readers uncomfortable: not softened nor redeemed, he is allowed to follow Stevenson’s logic to its conclusion. If Silver values freedom above all else, then that freedom must be tested against the most extreme forms of unfreedom of his time. And that means slavery.

This is where much of the resistance to Larsson’s novel originates: readers who are willing to accept piracy as a metaphor for freedom often recoil when that metaphor is forced into contact with historical reality. Larsson refuses to keep Silver in a morally sealed box. He places him in a world structured by colonialism, racial hierarchy, and the systematic enslavement of human beings, and weaves everything into a character that won’t do anything just out of idealism too. Crucially, Larsson does not turn Silver into a modern moral spokesperson, Silver does not suddenly acquire twenty-first-century ethics: his reflections on slavery are framed not by sentimental pity, but by a brutal recognition of contradiction and as an opportunity for him, who’s willing to think outside the box. He rejects slavery not because it makes him virtuous, but because he’s a man who has escaped forced labour, arbitrary punishment, and institutionalised violence, and he’s bound to recognise the structure when he sees it applied to others, but also because he sees the opportunity of gaining loyalty from the people he encounters, just as he tries to do with Jim.

By confronting slavery head-on, Larsson exposes the limits of romantic rebellion: freedom cannot be selectively applied without collapsing into hypocrisy, and the pirate who claims liberty while tolerating enslavement is not a rogue; he is a collaborator. Larsson’s Silver knows this, and his logical reaction becomes the novel’s most important engine. What unsettles many readers is not that Silver changes, but that he does not change enough: he remains violent, manipulative, self-interested. He does not become a hero in any comforting sense. Instead, Larsson shows us a man capable of recognising injustice without becoming clean in the process of reacting to it. This is precisely why the novel is important. Larsson forces the reader to abandon the fantasy that historical struggles for freedom were led by morally immaculate figures, he shows us that resistance often comes from those already compromised, already marked by violence, already excluded from respectable society. Silver’s rejection of slavery does not redeem his past crimes, but it does draw a clear political line. And that line matters.

By extending Stevenson’s character into the moral catastrophe of slavery, Larsson completes Silver where Stevenson only mentioned his woman. He reveals what was always implicit: that a commitment to freedom, if taken seriously, inevitably comes into conflict with the foundational injustices of its time.

Gentleman of Fortune, Enemy to Mankind

At first glance, the title Gentleman of Fortune and Enemy to Mankind reads like a pun, a contradiction designed to amuse with some sort of gallows humour. But Larsson is doing something far more precise: he is naming a political position.

To be a “gentleman of fortune” is not, in the piracy context, a claim to refinement or respectability but a declaration of autonomy, a rejection of sanctioned hierarchies, and fixed social roles. Fortune, here, is contingency. Movement. The willingness to stake one’s life on uncertainty rather than submit to a system designed to extract obedience.

The second half of the title — enemy to mankind — is where the discomfort begins because it forces a question that polite narratives prefer to avoid: which mankind? Historically, the label “enemy of mankind” (hostis humani generis) was invented to describe Commodus (yeah, the Gladiator guy) and was reserved for those whose violence was hideous and mostly unsanctioned. So let’s take a look at empires that could enslave, starve, flog, and massacre with legal authority. Pirates, in refusing that authority, were declared enemies not because they were uniquely cruel, but because they operated outside the moral monopoly of the state. Larsson’s Silver understands this perfectly. He does not pretend to innocence. He does not ask to be misunderstood. He accepts the label because he recognises it as a tool of power. To be named an enemy of mankind is to be placed beyond negotiation, beyond rights, beyond protection. It is the legal language used to justify extermination. And yet, Silver claims it.

By embracing the contradiction, Silver exposes the structure beneath it. A world that defines mankind in such a way that entire populations can be enslaved, exploited, or discarded has already declared war on itself. In that world, refusing to comply is automatically framed as hostility even when it’s simply a withdrawal from the system. If Flint wants a revolution that upturns the logics of maritime commerce and dies in alcohol because of this ambition, Silver does not seek to reform the system that brutalised him. This is what makes him politically unsettling. He does not believe in progress. He believes in survival, dignity, and negotiated loyalty.

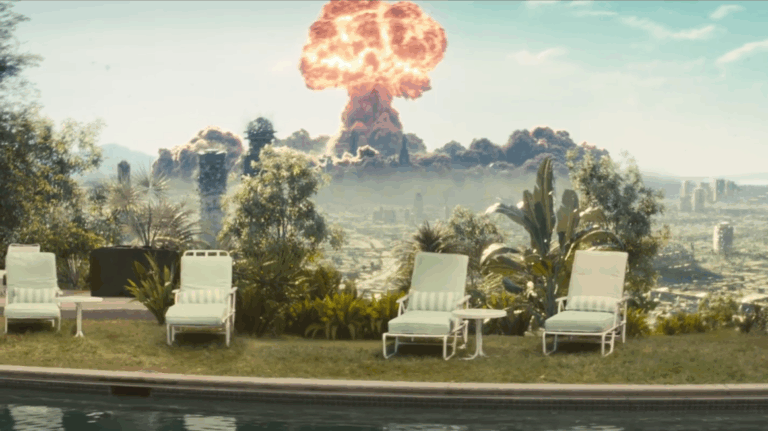

To be a gentleman of fortune in a structurally unjust world is to become an enemy of its moral fiction, and Silver’s crime is not simply piracy: it is the consistent refusal to legitimise a system that presents exploitation as order and obedience as virtue. This is why the title still resonates with me. Because we continue to live in a world where violence is considered acceptable when properly authorised, and unforgivable when it challenges the wrong hierarchies. Where freedom is celebrated rhetorically and punished materially. Where those who refuse to play along are branded enemies not of a state, but of “humanity” itself, whatever the fuck that means.

Larsson’s title forces us to confront an uncomfortable possibility: that being an enemy to mankind, as it is currently organised, may sometimes be the only way to remain loyal to human dignity. And, to quote the 1995 adaptation of Sense and Sensibility, piracy might remain the only valid option.

Long Live John Silver

Equality is Still a Mutiny

From the decks of eighteenth-century ships to the present day, the central conflict has not changed as much as we like to believe. Power still presents itself as order. Violence is still legitimate when it wears the right uniform. Inequality is still justified as a necessity, a tradition, economic realism, or it’s flat-out denied. And those who challenge these arrangements are still framed as dangerous, disruptive, unreasonable.

Silver belongs to our time because he understands something we keep trying to forget: equality does not emerge politely.

In the historical world that produced piracy, equality was a practical response to systematic abuse. Pirate crews did not draft articles because they were enlightened; they did so because the alternative was arbitrary violence, and there was plenty where they came from. They did not share spoils out of generosity, but out of survival. Equality, in that context, was a technology, a way to hold power in check when no external authority could be trusted. That logic has only changed shape. Larsson’s Long John Silver forces us to recognise that demands for equality are still treated as acts of insubordination. Whether the struggle concerns labour, race, gender, migration, or access to resources, the reaction is strikingly familiar: calls for fairness are reframed as threats to stability. Those who refuse exploitation are accused of extremism. Those who name structural violence are told they are exaggerating, politicising, or ruining an otherwise acceptable system. Silver would recognise these assholes immediately.

He would also recognise the discomfort of those who prefer their rebels sanitised. Characters like Silver become unacceptable the moment they refuse to remain symbolic. The moment their logic is extended beyond fiction, beyond the past, and into the present. We are happy to celebrate rebellion as long as it is safely concluded, historically distant, and morally uncomplicated, aren’t we? Well, fuck this. Larsson denies us that comfort. By insisting on the contradictions — freedom entangled with violence, resistance emerging from compromised figures, equality born of refusal rather than consensus — Long John Silver reminds us that progress has always involved mutiny: against ships, against laws, against economic arrangements presented as inevitable.

No Comments