A piece that started as a reflection around machine, human redundancies and artificial intelligence, and then all of a sudden started talking about smart working instead.

Happy Birthday Modern Times

A few weeks ago, Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times celebrated its 90th anniversary, and that sprang a conversation on how the movie’s misunderstood as an artwork against machines (I wrote a small thing here and on LinkedIn). This week, after some rumination, I’d like to expand upon that thought.

1.1 Anniversaries and Nostalgia: Teachers, leave the kids alone

Anniversaries are strange cultural devices, just like birthdays. They invite remembrance while, in fact, they quickly turn into simplification, particularly for capital works like a Charlie Chaplin movie, that everybody feels obliged to talk about and, I bet, very few actually took the pain to watch. A work is flattened into a slogan, a meme, a quote pulled out of context and made to circulate on social media; when it comes to works that are perceived to be about technology, it’s usually paired with a vague lament about how little has changed. In the case of Modern Times, the anniversary has once again revived a familiar reading: Chaplin as the prophet of a timeless struggle between humans and machines, the factory as a dystopian warning against technology itself.

It is an attractive reading, because it is easy, and because it resonates with a certain romanticism and the contemporary anxiety. Faced with automation, algorithms, and artificial intelligence, people instinctively reach backwards to find ancestors of our fear, and Modern Times seems to offer itself willingly: gears swallowing bodies, levers dictating movements, speed swallowing workers.

But this nostalgic gesture misses the point: by turning Modern Times into a generic anti-machine fable, we neutralise it, we make it say something comforting and vague — machines are dangerous, progress is cruel — while ignoring the much sharper diagnosis Chaplin was making. What Modern Times attacks is not the presence of machines, but the logic that governs their use. And that logic has very little to do with technology and everything to do with labour.

1.2. “Man vs Machine”: the Wrong Frame

The “man versus machine” framing is seductive because — even if it might sound like a paradox — it anthropomorphises technology. It gives us a visible enemy, something external and alien to blame, because the machine becomes a character, sometimes even a monster, endowed with agency, intention, and malice. Once that move is made, the analysis stops: if machines are the problem, then the solution must be to resist them, slow them down, or nostalgically imagine a return to a pre-mechanical world.

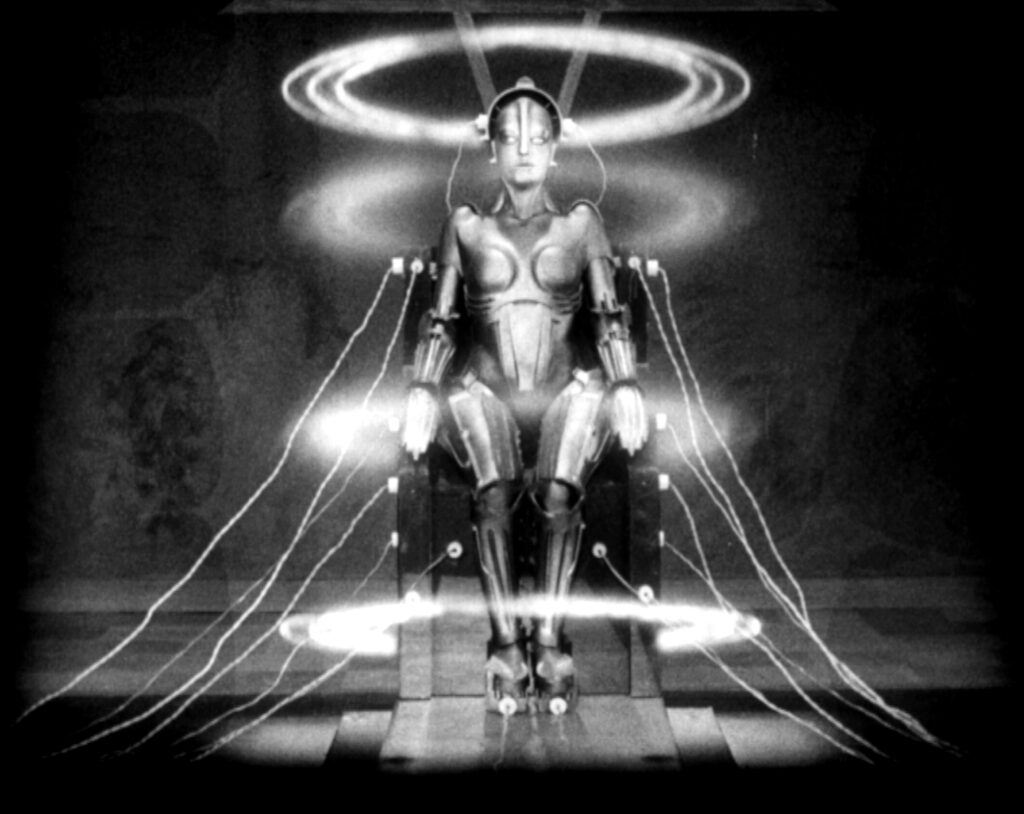

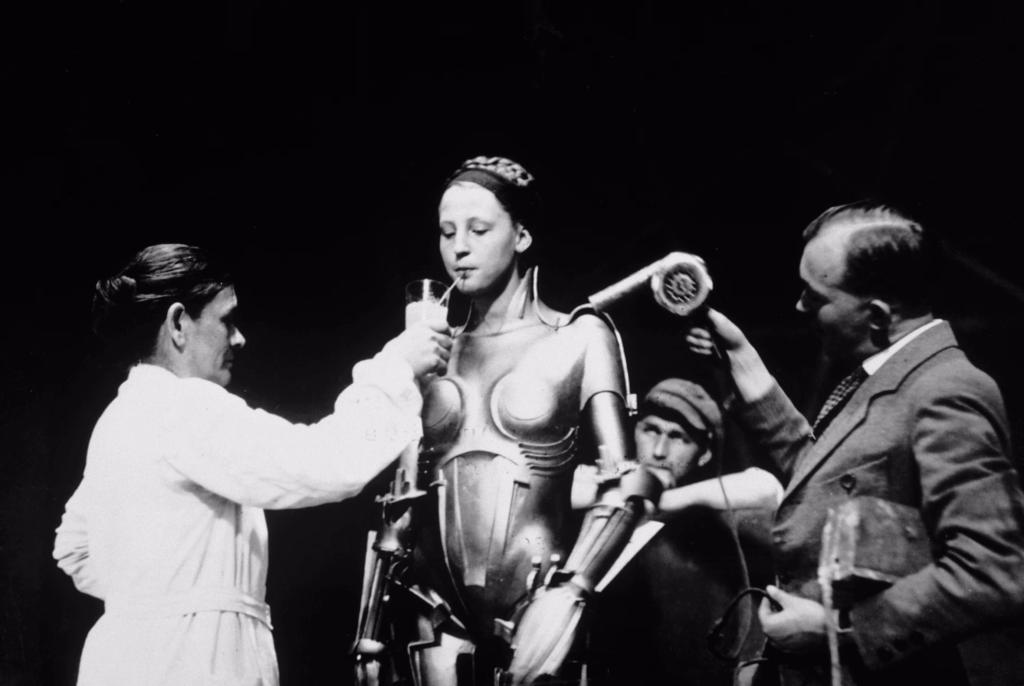

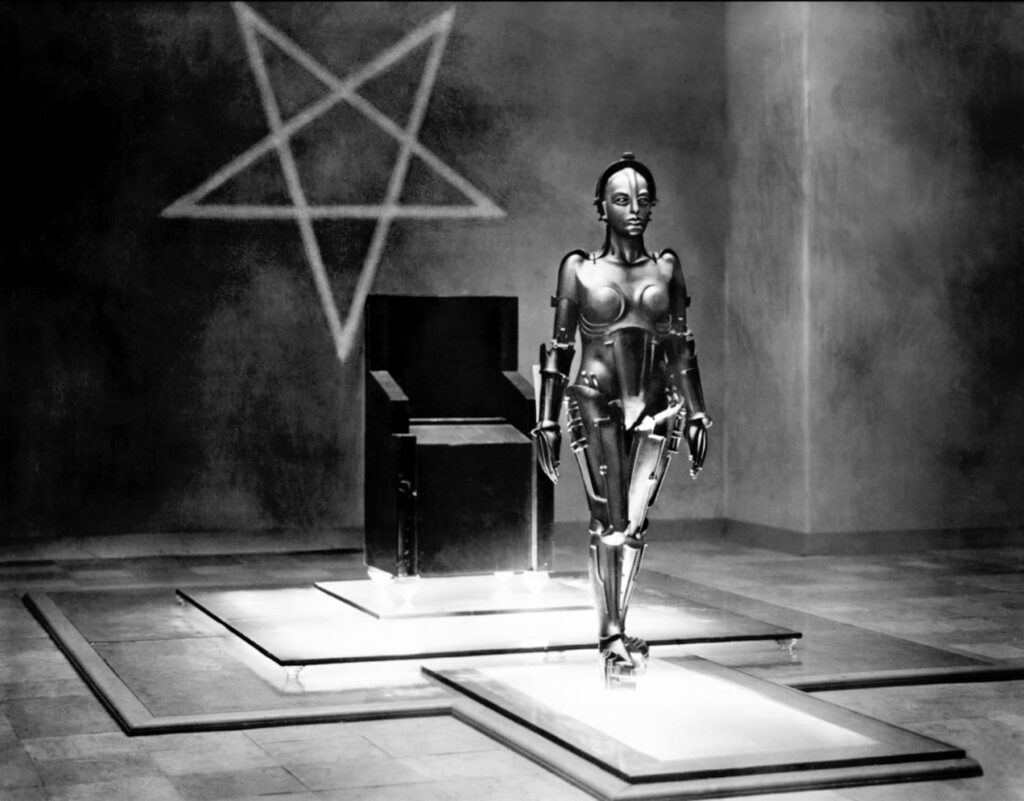

Both Modern Times and Fritz Lang’s 1927 Metropolis are often trapped in this reading. Chaplin is seen as mourning a lost artisanal past; Lang as warning against an industrial future that devours its workers. Yet neither film actually supports this opposition. Machines in these movies do not rebel, do not decide, do not act on their own. They never exceed the role assigned to them. They execute, relentlessly and obediently, a script written elsewhere, and the problem is the script. Which, spoiler alert, was written by humans.

Although Modern Times and Metropolis differ radically in tone, scale, and aesthetic ambition, they are often mistakenly placed on opposite ends of a spectrum: Chaplin as humanist comedy, Lang as technophobic dystopia. Although I have a preference amongst the two, not being a fan of comedy in general, I think this opposition is misleading. Both films emerge from the same historical tension and articulate the same structural critique, using different cinematic languages: where Chaplin works through the body — through slapstick and repetition meant to convey exhaustion — Lang operates through architecture, myth, and mass choreography.

What these films stage, in my opinion, is not a conflict between humans and machines, but a conflict between humans and an organisation of labour that treats human activity as decomposable, abstract, and optimisable. The machine is not the antagonist; it is an instrument that comes after violence already happened, a violence that doesn’t originate in steel and gears but in the decision to reorganise work as a sequence of isolated gestures, stripped of meaning, context, and agency. This distinction matters, because the “man vs machine” narrative quietly absolves men of responsibility, and that’s not the story in neither movies. In both cases, the factory is never the origin of violence: its machines are the visible interface of an invisible order. Reading these films together allows us to see that what appears as a conflict between humans and machines is, in fact, a conflict between humans and the way work has been organised around them. Only by keeping this shared diagnosis in view does it make sense to separate the two films and examine how each constructs its critique, one through comedy and failure, the other through spectacle and sacrifice.

1.3. Fragmentation of Labour is the Real Antagonist

At the heart of both Modern Times and Metropolis lies the same idea: craft has been broken apart and turned into mechanical labour. When tasks are fragmented, gestures isolated, bodies synchronised to rhythms they do not control and cannot understand, the worker no longer relates to a purpose, a finished product or even a full action, but only to a fraction of a process, endlessly repeated and easily replaceable. That’s how people get replaced by machines: by turning their craft into a mechanical repetition, by transforming their craft into something we would rather ask a machine.

This fragmentation is what makes automation possible — with the promise of affordability for products that were luxury — but also what makes it devastating. Once work is decomposed into simple, measurable units, it can be standardised, accelerated, and eventually delegated to machines not because machines are inherently superior, but because the work has already been redesigned to resemble them. In this sense, machines do not replace human labour; they inherit it after it has been sufficiently impoverished.

What disappears first is authorship, and employment just follows. This is the real anxiety these films articulate, long before contemporary debates on artificial intelligence: a world in which craft is reorganised into workflows, pipelines, and chains of execution. Seen through this lens, Modern Times and Metropolis stop being warnings against technology and become critiques of the specific ideology of efficiency that mistakes fragmentation for rationality. The machine, far from being evil, is merely the mirror in which this ideology recognises itself.

1.4. It’s not my idea

But it’s a good idea nonetheless.

Before entering the factory floors of Chaplin and the machine halls of Lang, it is useful to introduce a conceptual tool that helps make explicit what these films already show intuitively. In The Eye of the Master, Matteo Pasquinelli dismantles one of the most persistent myths surrounding automation and artificial intelligence: the idea that machines “replace” human intelligence through their own autonomous evolution. Instead, he argues that what we call machine intelligence is the result of a long historical process of fragmentation, measurement, and reorganisation of human labour.

At the centre of Pasquinelli’s analysis is the act of panoptical control. Automation requires control: tasks must be rendered legible, comparable, and measurable before they can be automated. This is what Pasquinelli calls the “master’s eye”: a supervisory gaze that abstracts work from bodies, contexts, and intentions, transforming it into data, metrics, and repeatable operations. Only once labour has been sufficiently formalised does the machine appear capable of performing it. More than that: once labour has been fragmented, we feel automation is mandatory because we wouldn’t want any human to perform that kind of repetitive, small-scale task, forgetting that this task was deliberately created in the first place.

This perspective is crucial because it reverses the usual causal narrative: machines do not impose fragmentation upon labour; fragmentation prepares labour for machines. Automation is not the origin of alienation, but its consequence. What appears as technological domination is, more accurately, organisational domination expressed through technology.

Seen through this lens, both Modern Times and Metropolis reveal an uncanny theoretical precision: long before cybernetics, information theory, or artificial intelligence, both films stage worlds in which human activity is reorganised to fit the requirements of supervision and control. Workers are made machine-like. Their contribution is reduced to the single task, simplified, and stripped of autonomy so that they may be observed, accelerated, replaced, and eventually delegated: Pasquinelli’s contribution allows us to read the machines in these films not as agents, but as symptoms, the visible endpoints of an epistemic process. Once creativity is reframed as workflow, it becomes optimisable. The “evil machine” is therefore a narrative illusion that conveniently obscures the prior violence of organisation.

2. Modern Times: a Grammar of Fragmentation

Modern Times opens with a rhythm that will dominate many of its sequences, as the factory is introduced: conveyor belts, rotating cogs, and synchronised gestures establish a visual grammar based on repetition and interruption. Chaplin adopts the assembly line as a cinematic device.

Commentaries such as the one by David Robinson have noted how Chaplin’s factory sequences are constructed around tempo rather than narrative progression, with gags emerging from acceleration and loss of control rather than from plot development (you can flick through Robinson’s Chaplin: His Life and Art at this address). The assembly line dictates the pacing of the film, compressing time and forcing the body. The factory does not function as a backdrop, nor does it turn into a character, but it dictates the narrative rhythm just as much as it dictates the characters’ lives. Its logic structures what can happen on screen, determining gestures, timing, and even comedy itself. The machine is therefore less an object than a language, one that speaks through speed, standardisation, and enforced synchrony.

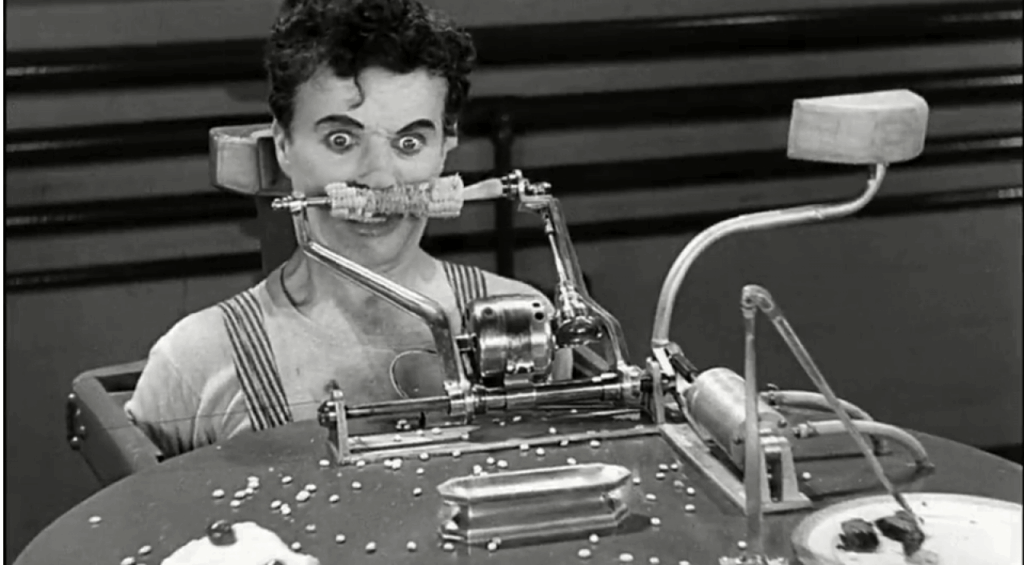

Within this grammar, Chaplin’s body becomes the primary site where tension accumulates: the Tramp, as Chaplin’s character is called throughout a series of movies that ends with Modern Times, does not oppose the machine through sabotage or refusal, but he attempts, sincerely and obsessively, to comply. As Miriam B. Hansen observes in her essay “The Mass Production of the Senses”, the comedy of Modern Times emerges from the body’s attempt to internalise industrial rhythms beyond its limits. The famous sequence in which the Tramp continues tightening imaginary bolts after leaving the assembly line is not simply a joke about madness and obsession, but visualises the persistence of industrial discipline beyond the workspace, inscribed directly into muscle memory. The body becomes fragmented in parallel with labour. Hands act independently of intention, reflex overtakes decision, and movement loses its relation to purpose, and thus Chaplin’s performance exposes the cost of this reorganisation: the body is a relay point for commands generated elsewhere. Nowhere this concept is clearer and more unsettling than in the sequence of the feeding machine.

The demonstration of this infernal machine is one of the most often cited sequences in Modern Times, sometimes read as a satire of technological excess, and yet it’s the one in which the target of the satire is clearere: the machine is designed to eliminate the lunch break, the dream of every employer. Its function is organisationally vexatory.

As Chaplin himself explained in his Autobiography, the idea for the scene came from contemporary experiments aimed at maximising productivity by minimising downtime, something corporations like Amazon haven’t given up upon. The violence of the feeding machine lies in its redefinition of care as a logistical problem where eating becomes a task to be optimised, timed, and integrated into the production cycle, just like any other task.

Film theorist Siegfried Kracauer, in his Theory of Film, noted that such moments reveal how rationalisation extends beyond labour into the management of life itself, if left unchecked, and the feeding machine fails because its underlying premise erases the human meaning of the activity it seeks to automate. The Tramp’s body, once again, exposes this contradiction through discomfort, spillage, and total chaos. Automation just gloriously manifests as an extension of managerial imagination, and the machine performs exactly what it was designed to do; the absurdity lies in the goal it serves.

Another strikingly relevant point in Modern Times is the productivity without meaning, where speed becomes a request towards maintaining discipline in the factory, and it’s utterly pointless. More appropriately, speed dominates Modern Times but it is never portrayed as productive in any substantive sense: Chaplin’s language accelerates gestures to convey the idea that the factory compresses time and demands constant attention. Does this sound familiar? And yet, in the very material reality of the assembly line, the outcome remains abstract: the Tramp never sees a finished product, never understands the purpose of his task, never connects effort to result.

This disconnect aligns closely with what Harry Braverman would later describe as the separation of conception from execution in industrial labour (read Labor and Monopoly Capital if you want to know more). Chaplin visualises this separation through endless motion that replaces meaning: activity is its own justification, just as it happens when they ask you to “return to the office” because they can’t evaluate whether your work is meaningful beyond warming the chair with your bum.

Efficiency functions as discipline, and mindless speed enforces obedience by preventing reflection, coordination, or improvisation. This is why the system of Chaplin’s factory doesn’t collapse when the Tramp falters but simply ejects him, recalibrating around his absence. What matters is not who performs the task, but that the task remains performable. By the end of the factory sequences, Modern Times has established its central insight: it’s true that, once work is reorganised as a chain of isolated gestures, the human presence becomes incidental but machines do not introduce this condition; they stabilise it. The real transformation occurs earlier, in the decision to value speed over sense, execution over understanding.

To truly grasp the consequences of this paradigm, let’s shift to Metropolis.

3. Metropolis: Fragmentation at Monumental Scale

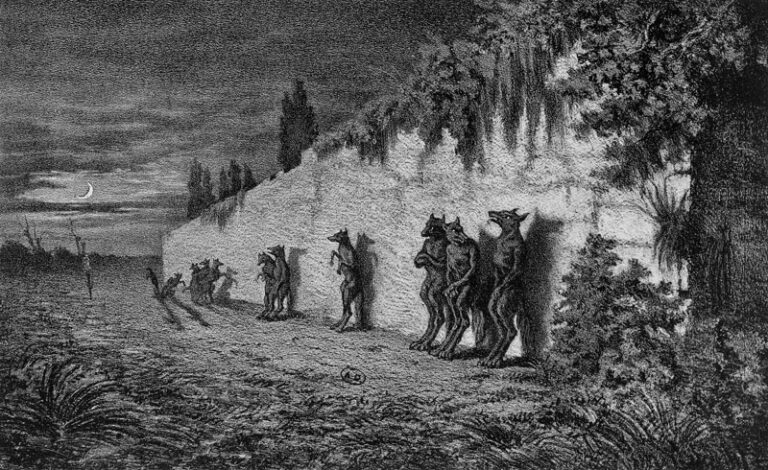

Few images in cinema have been as persistently misread as the Moloch sequence in Metropolis: workers are swallowed by a gigantic machine, reimagined as an ancient god demanding human sacrifice and called after a god that the Bible associates with a human sacrifice by fire. This scene is often cited as evidence of Lang’s technophobia, yet I think it’s fair to say that its symbolism points elsewhere.

Below, you can watch the sequence paired with the original score by Gottfried Huppertz (yeah, silent movies weren’t meant to be watched in silence).

As Siegfried Kracauer observed in his fairly intense From Caligari to Hitler: Psychological History of the German Film, Metropolis does not depict machines as autonomous forces but as objects of worship, something we can easily place in connection with contemporary sensibilities through the acute observations of Yuval Noah Harari when he talks about the sovereign algorithm.

In Metropolis, the reflection is simpler: the machine becomes divine only because labour has been reorganised into ritual, something I actually heard employers stipulate as a necessity. Workers move in synchrony, repeat prescribed gestures, and submit their bodies to a system whose purpose remains opaque. The religious imagery does not condemn technology, in my opinion: it exposes how industrial labour has taken on the structure of cultic obedience.

In this, Moloch is not a machine-god that demands sacrifice of its own will: Lang would have had both the means and the imaginative tools to portray such a creature, if he wanted. The machine is a projection of social relations. The transformation of the engine into a deity visualises how abstraction produces mystification: once labour is detached from meaning, its organising structures acquire a mythical aura and power appears transcendental because its material logic is no longer visible. As we were saying for Modern Times, workers never see the outcome, and this is a way of the system to control them.

Thomas Elsaesser, in his relatively recent monographical work on Metropolis, notes that Lang’s city is organised with a radical separation between production and consumption, a separation that’s spatial, social, and symbolical. The result of this separation, that manya asshole architects actually predicated as something good for our cities, is abstraction: labour is a function, rather than an activity, defined by compliance with indicators, and you can argue that nobody knows what actually happens inside the factory just as very few people know, for instance, how their Amazon purchases land on their doorsteps within just a few days.

Fragmentation here is not merely temporal, as in the assembly line, but architectural at a larger scale: the vertical city encodes division with intellect above, execution below. Visibility flows upward. Workers relationship to work is mediated entirely through symbolic representations — gauges, clocks, signals — and that might just be Lang being Land but the result is a replacement of direct experience with symbols and belief. Work as a religion, as we were saying. Observation, calculation, and decision-making are removed from execution, and the workers’ knowledge shrinks as their tasks become more precise. Intelligence is redistributed, not eliminated, but that might be the final goal after all.

If we have to believe Anton Kaes when he describes spaces as zones where individuality dissolves into function (Shell Shock Cinema: Weimar Culture and the Wounds of War), we must also recognise the machine room as a temple, vast, symmetrical, and oppressive, where work is staged as an offering rather than a contribution to society. Workers rotate in and out like replaceable components, their presence acknowledged only insofar as it sustains the system’s continuity. When a worker falters, other steps in and the machine never reacts. Sacrifice, in this context, is structural: it’s not the result of malfunction or cruelty, but of indifference, and you can’t get more relevant than that. The system does not require suffering to function, but it doesn’t register it either. This is why the machine appears monstrous: its smooth operation renders human cost invisible. Yet, as in Modern Times, the machine behaves impeccably, doesn’t exceed its mandate. The violence emerges from the conditions under which labour is inserted into the system, not from the system’s mechanical components.

Elsaesser points out that the true power in Metropolis resides in coordination: the system’s intelligence lies in its design, its capacity to orchestrate flows of labour without requiring constant intervention. This distinction matters because it undermines the idea of technological determinism. The machines of Metropolis do not rebel, evolve, or dominate: they stabilise an existing order by making it durable and scalable. Fragmentation of labour allows this stability: once craft is decomposed into discrete operations, it can be redistributed across bodies or devices without altering the system’s logic.

Lang’s machines and their apparent tyranny reflect the rigidity of the organisational structures they serve. By the end of Metropolis, the machine stands revealed as an artefact that concentrates, amplifies, and enforces decisions already taken. Like Chaplin’s factory, it is a mirror. What it reflects is not technological ambition, but a vision of labour stripped of agency, continuity, and meaning. And that’s what’s happening today: way before generative AI stepped into the picture and scared people, the organisation of creative labour and the demands of the industry should have outraged you.

4. Creative Labour on the Assembly Line

4.1. The Industrial Dream of Decomposing Intelligence

One of the most persistent fantasies of industrial modernity is that intelligence can be decomposed, disassembled, split into components, stabilised into procedures, and redistributed across roles. This fantasy predates digital technologies by decades, and it’s already present in Taylorist management, where thinking is extracted from execution and relocated into planning, supervision, and optimisation.

What changes in creative labour is not the logic, but the object of decomposition. Instead of gestures or physical tasks, it is imagination, judgement, and interpretation that become targets of reorganisation. The creative endeavour is reframed as a sequence of steps: ideation, refinement, execution, polishing. Each step is assigned to a role, each role to a worker, each worker to a measurable output.

This is one of the condition under which machines appear most capable of creative work, not because they invent (I wrote about this possibility here), but because creativity has already been remodelled as a workflow. Pasquinelli’s argument applies here with particular force: once intelligence is formalised into observable operations, it becomes transferable. The machine does not steal creativity; it arrives after creativity has been redefined as a pipeline. The language of contemporary creative industries makes this continuity explicit: film studios, game developers, and design firms speak of pipelines, throughput, bottlenecks, and optimisation. These terms do not describe artistic vision; they describe coordination. Their function is to ensure predictability at scale.

4.2. From Taylorism to Creative Pipelines

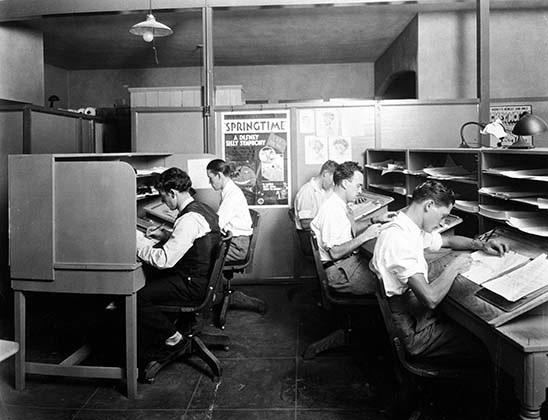

In the movie industry, character design offers a clear example: what could have been a fluid process of exploration was fragmented across concept artists, modellers, riggers, animators, texture artists, lighting specialists, and colourists. Walt Disney had a crucial role in inventing this fragmentation, and that’s why his studios resembled factories, with gender division mirroring the perceived complexity, nature and worth of the task.

Each role handles a tightly circumscribed portion of the character’s existence, often without visibility into the whole. Decisions are inherited rather than authored. Animation scholars such as John T. Caldwell (Production Culture: Industrial Reflexivity and Critical Practice in Film and Television) have shown how this segmentation increases managerial control while diminishing creative autonomy and, arguably, decreasing the quality of the final product favouring its scalability and time-to-market. The so-called creative pipeline allows studios to parallelise work, outsource segments, and replace contributors with minimal disruption. Under these conditions, automation appears as a logical next step and, sometimes, an aid to the poor creative worker under stress.

A similar dynamic unfolds in the videogame industry: concept artists, in particular, are increasingly evaluated on speed and volume, rather than depth, and the demand to produce dozens of sketches per day turns exploration into iteration without reflection. The sketch ceases to be a thinking tool and becomes a token in a production system, under the false assumption that sketching until your hands fall off helps you purge your mind of those harmful things we call ideas.

This is where dehumanisation begins, as in Chaplin’s factory: not with software, but with tempo. When the time allocated to thinking collapses, judgement becomes implicit, unspoken, and therefore replaceable. Generative AI tools enter a space that has already been emptied of deliberation.

4.3. Conclusion: when Thinking is broken into Tasks, it becomes Mechanisable

Architecture and design provide a particularly revealing case, because they make visible the fiction underlying many organisational models. I’m talking about the forced separation between architects and engineers on one side, and drafters and modellers on the other, a separation that assumes thinking happens upstream, while execution happens downstream. Design decisions are treated as discrete events that can be completed and handed off.

In practice, this distinction is bullshit. First of all, because modelling, annotating and coordinating information are not neutral acts: they require interpretation and continuous adjustment. Design happens while drawing, just as it happens while modelling. The attempt to separate these functions is not descriptive: it is prescriptive and just another act of control aimed at paying everybody less and, ultimately, replacing some of them.

Some countries nonetheless succeeded in enforcing this division, at least on paper. Switzerland is often cited as an example where regulatory and contractual frameworks institutionalised the split between conception and execution. I’ve never encountered a situation in which the result was clarity: the result is fake abstraction and, if you talk to the drafters, they’ll tell you their work is circomvoluted and complicated, and the do just as much engineering as the engineers, while the engineers themselves will lament reworks and not being able to bring their point across to “the kids”. Meanwhile, knowledge was displaced from the point where problems actually emerge. Once again, this prepares the ground for automation of the bad kind. When modelling is framed as the mechanical transcription of decisions made elsewhere, replacing the modeller with a machine appears reasonable. What disappears in this framing is the distributed intelligence embedded in the act itself.

Across these industries, the pattern repeats. Thinking is decomposed into tasks. Tasks are isolated, standardised, and accelerated. Meaning is replaced by compliance with a specification. Only then does the machine seem capable of stepping in.

The anxiety surrounding generative AI in creative fields often misses this sequence. The threat does not originate in artificial intelligence itself, but in the long-standing effort to treat intelligence as an assemblage of operations. Automation becomes credible only after imagination has been reorganised to resemble a machine.

Foreword — (Don’t) Rage Against the Machines

If Modern Times and Metropolis still feel unsettling after nearly a century, it is not because machines have grown more powerful but because the logic those movies diagnosed has remained remarkably stable and lies at the heart of our post-industrial society. The real continuity between the factory floor, the studio pipeline, and the contemporary discourse on genAI lies in the persistent effort to fragment work in the name of efficiency, control, and scalability.

Resisting this logic does not mean rejecting technology, nor returning to an obtuse and unattainable idea of a Vitruvian Beings that can accomplish any craft in its entirety by themselves. It means refusing a specific organisational fantasy: that intelligence, creativity, and judgement can be cleanly decomposed, redistributed, and recomposed without loss. What Chaplin and Lang both showed, each in their own language, is that something essential disappears when work is stripped of continuity and agency. What disappears first is meaning; automation follows later to fill in the gaps.

A useful contemporary counterexample comes from a somehow unexpected place: videogames. Baldur’s Gate 3 stands out not merely for its commercial or critical success, but for the production choices behind it. Larian Studios deliberately resisted hyper-fragmented pipelines, favouring long feedback loops and cross-disciplinary collaboration. This has been narrated by voice actors (pun intended) who were not treated as downstream executors of pre-defined characters, but as contributors to their development. Performances informed writing; writing informed mechanics; mechanics reshaped narrative possibilities. This was not a nostalgic return to artisanal production: it was a strategic choice to tackle a complex work and preserve wholeness. By allowing contributors to see, influence, and understand the larger structure of the work, Larian made creativity harder to abstract, and therefore harder to automate away. The result was acceptable inefficiency: it took them six years to produce the videogame. Compare that time with times of larger companies who fragment creative work and you’ll see that time isn’t the issue (and you can start from here if you have no idea what I’m talking about).

Similar signals appear elsewhere. In animation, smaller studios experimenting with integrated teams — where storyboard artists, animators, and directors iterate together rather than through rigid handoffs — report fewer revisions and stronger visual identities. In architecture, practices that resist the forced separation between design and delivery (through Integrated Concurrent Engineering sessions, for instance) rediscover that modelling, annotating, and coordinating are not manual tasks, but sites of continuous decision-making. In software development, movements like cross-functional teams and product ownership attempt, imperfectly, to restore responsibility and vision to those who execute the work.

These examples point in the same direction: resistance does not take the form of luddism (though those guys were right) but of reorganisation that consists in rebuilding contexts where work can be understood as a whole, where contributors retain visibility over outcomes, and where thinking is allowed to occur throughout the process rather than being confined to an upstream phase. From this perspective, genAI is neither the enemy nor the saviour. It will amplify whatever organisational logic it encounters. In fragmented systems, it will accelerate dispossession. In holistic ones, it may well remain a tool, useful, limited, and subordinate to human judgement.

The lesson of Modern Times is not that machines dehumanise us. The lesson of Metropolis is not that technology becomes tyrannical. Both films insist on something more precise and more demanding: when work is organised in ways that deny meaning, dehumanisation follows, whether the tools involved are gears, cameras, or models.

No Comments