A few weeks ago, I wrote about an installation with pieces by Giorgio Armani at the Pinacoteca di Brera, here in Milan, and as a matter of fact that wasn’t the only show around fashion I visited, which is unlike me. While I was in Venice in January, I stepped into the Fortuny Museum, completely by chance, as I had an hour to kill. I knew the guy from back in the day when I was working next to interior designers for Piero Lissoni, as one of them was very fond of Fortuny lamps, but I only had a vague notion of his contribution to the world of fabrics, and I knew nothing of his work in theatre, so the museum was a very pleasant surprise.

Mariano Fortuny: who was this guy?

Mariano Fortuny y Madrazo is one of those figures who seem to have come straight out of the Renaissance. Painter, inventor, scenographer, photographer, fashion designer, chemist, collector. His restless intelligence connected art and science, tradition and experimentation, Venice and the modern world.

Born in Granada in 1871, Fortuny grew up immersed in art: his father, Mariano y Marsal, was a celebrated Romantic painter with a knack for Orientalism, and his mother, Cecilia de Madrazo, came from a family in which the title of curator at the Prado seemed to be inherited from father to son. Fortuny’s personality, though, was markedly different from that of the virtuoso painter-genius often associated with the 19th century: he was reserved, methodical, and profoundly curious. Rather than seeking mastery of one medium, he pursued coherence across many.

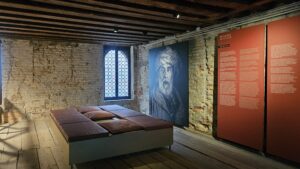

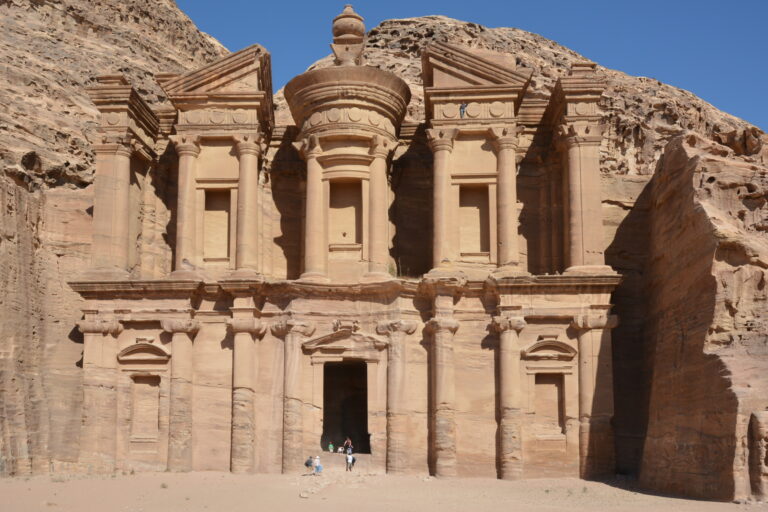

This disposition shaped both his life and his work. Venice, where he settled permanently at the end of the 19th century, was an intellectual catalyst and deeply fascinated him, with its layered history, its fading grandeur, its obsession with light and surface. Palazzo Pesaro degli Orfei — where the Fortuny Museumstands today — became a residence and a laboratory: a place where textiles, pigments, lighting systems, stage sets, photographic plates and ancient objects coexisted in productive disorder, as they still do today.

Three are the main aspects youb can mainly see here: painting and decoration, fashion and textiles, and theatre, with a digression on the splendid lamps.

Fortuny: the Painter and the Photographer

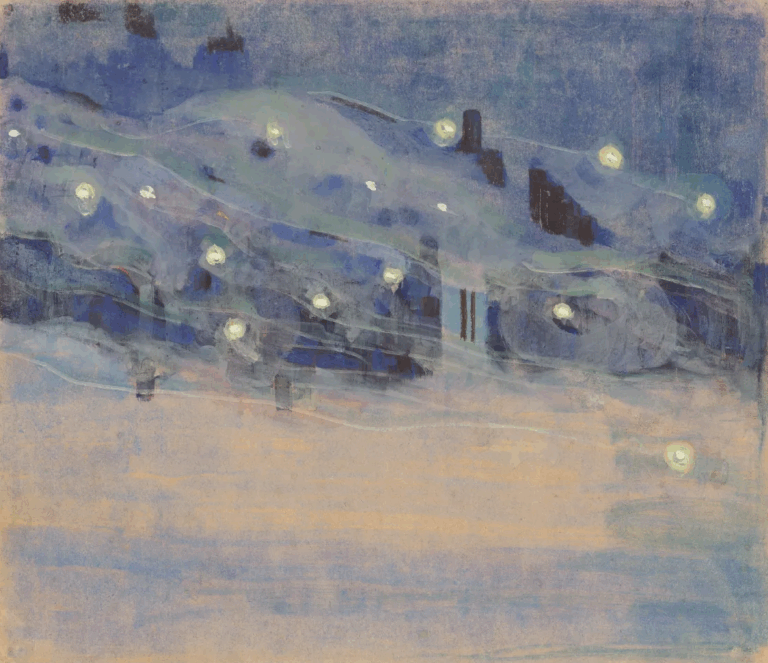

Fortuny treated art as a process of investigation and his paintings, often overshadowed by his work in other fields, reveal this clearly: they are mostly studies, of light and atmosphere and tone, rather than finished works. He was fascinated by how light behaves on surfaces, how it can be diffused, reflected, sculpted. This fascination would later find fuller expression in theatre and textile design, where light became both a material and a subject.

Photography also played a crucial role in this research-oriented approach: Fortuny used photography to analyse and freeze light, to study contrasts, textures, and spatial relationships, and to stage what looked more like constructed behind-the-scenes of plays that never were. In many ways, photography was the bridge between his artistic sensibility and his technical experimentation.

Fortuny: the Stage Architect

Fortuny’s contribution to theatre was radical. At a time when theatrical staging relied heavily on painted backdrops and rigid lighting, he imagined something different and astonishingly contemporary: a dynamic, immersive space shaped by light itself.

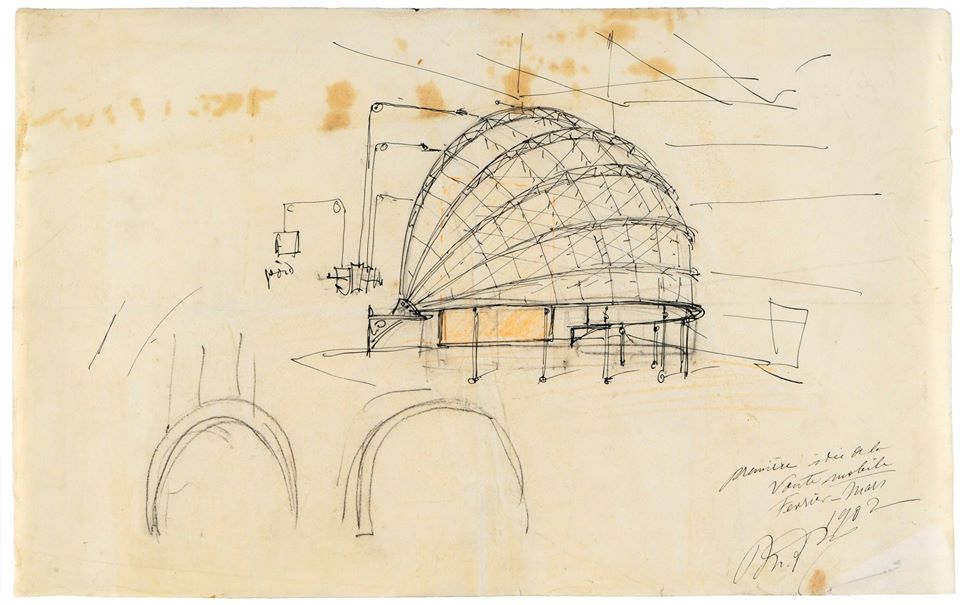

He developed an innovative lighting system, patented in the early 20th century, that transformed how stages were illuminated through the introduction of an indirect lighting dome, that created atmospheric depth, eliminated harsh shadows, and allowed gradual transitions of mood. Instead of telling the audience where to look, light became a subtle guide more akin to music.

Equally important was his conception of scenography as an integrated whole where sets, costumes, lighting and space were not separate departments but parts of a single visual language. This holistic vision anticipates modern stage design and even contemporary immersive installations, if you think about it, and it’s an architect’s approach: instead of designing decorations, he designed environments.

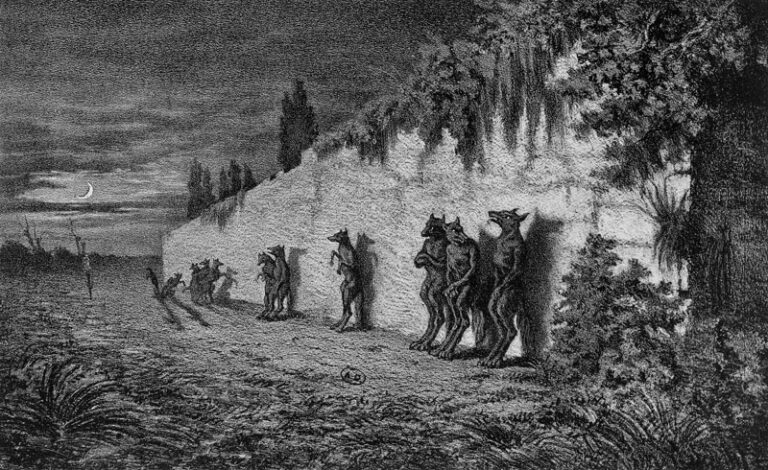

Fortuny’s work intersected with that of Gabriele D’Annunzio at a crucial moment for Italian theatre and aesthetics. The two shared a deep fascination with classical antiquity, symbolism, and the idea of art as a total, immersive experience, and Fortuny contributed to productions of D’Annunzio’s plays — most notably Francesca da Rimini — through his innovative lighting systems and scenographic concepts. In these works, light ceased to be a neutral technical element and became a poetic force, shaping the emotional rhythm of the drama and amplifying its symbolic intensity. D’Annunzio recognised in Fortuny a co-author in shaping the atmosphere and the emotional impact of what was happening on stage, someone capable of translating words into shadow and glow. This collaboration reinforced Fortuny’s conviction that theatre should be a synthesis of arts, where technology serves poetry rather than spectacle for its own sake.

Fortuny: the Fashion and Fabrics Designer

If Fortuny is widely remembered today, it is largely because of fashion, in particular the Delphos gown.

Inspired by ancient Greek sculpture, the Delphos dress was revolutionary in its simplicity and technical sophistication: made of finely pleated silk, dyed using secret processes that came from Venice’s tradition in printing, it followed the body with no corsetry, no rigid structure, no excess. The dress moved with the wearer, responding to light and gesture. Marcel Proust himself found the clothing “faithfully antique but markedly original,” and indeed Fortuny didn’t want to create a costume and didn’t copy antiquity; he translated its principles — freedom, proportion, harmony — into modern materials and techniques. Though echoing the fashion trends of Art Deco, his garments were timeless by design, intentionally detached from trends, and you could easily wear them today.

Fabric printing was one of the areas where Fortuny’s hybrid mind — at once artistic and technical — found its most refined expression: he developed and patented innovative printing methods that allowed pigments to penetrate the fibres of silk and velvet with unusual depth and durability, producing patterns that seemed to emerge from the fabric rather than sit on its surface. Drawing on Renaissance motifs, Islamic geometries and ancient symbols in a way that’s imbued with the atmosphere you still breathe in Venice today, Fortuny treated pattern as a culturally layered language. Each design was the result of meticulous experimentation with dyes, metallic powders and fixatives, often carried out in secrecy within his Venetian workshop. The resulting textiles interacted subtly with light, changing in intensity and tone as the viewer moved, and it’s pure magic.

Derived from the same principles that guided his stage lighting — diffusion, reflection, and atmosphere — his lanterns are at the crossroads between theatre and fashion: they were designed to soften illumination rather than dominate it, and they were crafted using pleated silk shades, often printed with his own patterns. Though they don’t have their own section and focus in the museum, you’ll see them hanging around everywhere. Take your time to appreciate them.

Palazzo Pesaro degli Orfei

Long before becoming inseparable from Mariano Fortuny’s name, Palazzo Pesaro degli Orfei had already lived several lives, and it’s worthy of a visit in itself.

It was built in the late Gothic period and reflects the complex stratification typical of Venice. It was first associated with the Pesaro family, a prominent Venetian patrician lineage since the early 13th century whose members served the Republic as admirals, magistrates, high officials and patrons of the arts, managing to be Doge for like one year at a certain point. In the 19th century, it was known as the Orfei, a venue for concerts and musical performances. When Fortuny acquired and transformed the palace at the end of the century, he kept the spaces as hybrid spaces where medieval tapestries coexisted with photographic equipment, stage models with ancient sculptures, bolts of fabric with lighting prototypes. The palace still has this vibe today.

No Comments