In the rich tapestry of 20th-century Italian art, Felice Casorati is a figure of striking elegance and introspection at the crossroads of symbolism, metaphysical painting, and the classic Italian tradition. Casorati did not simply paint; he composed visual odes to silence, to structure, and to the inner life of forms. His work stands as a compelling testament to the contemplative potential of art in a world increasingly drawn to speed and spectacle. Now you go ahead and tell it’s not relevant.

What draws me most to Casorati’s work is the paradox he mastered: the ability to infuse rigid geometry with raw emotion. His paintings—seemingly cold and constructed—are in fact vibrantly alive with inner tension whether he portrayed women in long, static poses or still lifes arranged with almost scientific care, there is always something stirring beneath the surface. His figures, so serene, often radiate a subtle anguish or longing, suspended in rooms that seem both timeless and placeless. It’s as if he painted the architecture of the soul.

Casorati’s love of structure owes something to his early training in music and his brief foray into law before he fully committed to painting. The discipline of those pursuits shines through in his canvases, where each element seems deliberately placed, not a stroke out of order, yet the result is never sterile, and the quietude of his compositions invites the viewer into a space of reflection. There is a rhythm to his work that resonates like a sonata played in a hushed room.

In paintings such as Silvana Cenni (1922), one sees Casorati’s mastery of psychological depth. The young woman’s distant gaze, her elongated form, her enthroned pose like a Priestess of Tarots, the delicately flattened perspective—all contribute to a sensation of stillness so profound it feels sacred. In that space, the viewer is a participant in an unspoken conversation between presence and absence.

Maybe this is why Casorati is often linked to the metaphysical painting of de Chirico and Carrà, and while the connections are there—particularly in his use of empty, dreamlike spaces—he is no imitator. Where de Chirico’s cities are haunted by mystery and dread, Casorati’s interiors are imbued with restraint and calm. His classicism is not nostalgic but modern, a response to chaos with clarity. And yet, what I find most profound is that his classicism is never cold. In Casorati’s work, the past is not a relic but a living guide. He speaks to us not through grand gestures or historical narrative, but through the poetics of line, form, and gaze. His figures may be frozen in time, but they pulse with quiet intensity.

The Show

From February 15 to June 29, Palazzo Reale in Milan hosts a major retrospective dedicated to the influential Italian artist. This exhibition marks Casorati’s return to Milan after 35 years, following his last major show at Palazzo Reale in 1990. Curated by Giorgina Bertolino, Fernando Mazzocca, and Francesco Poli, the exhibition features over 100 works, including paintings, sculptures, drawings, and stage designs, offering a comprehensive overview of Casorati’s artistic journey.

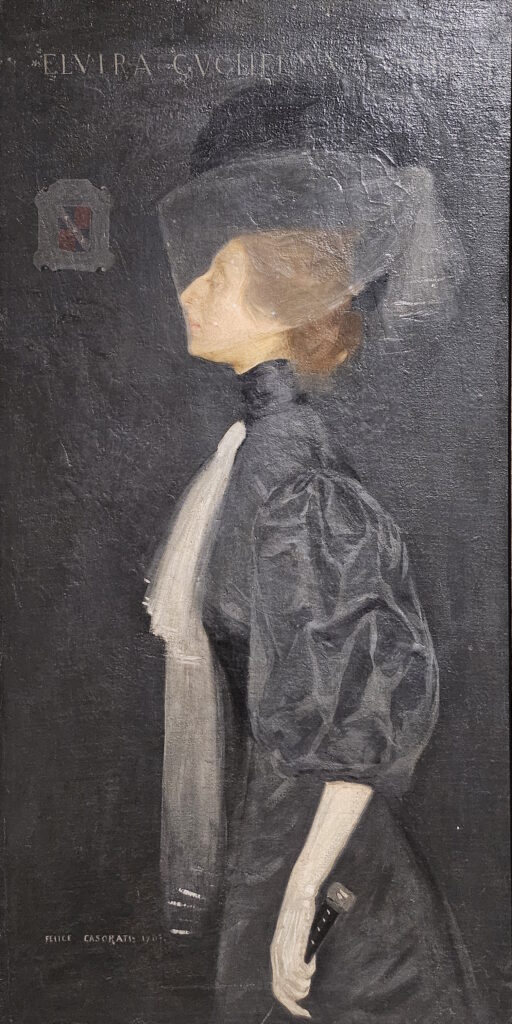

The exhibition is organised chronologically across 14 rooms, tracing Casorati’s evolution from his early realist and symbolist works to his mature style characterised by metaphysical and magical realism elements. Notable pieces on display include “Ritratto della sorella Elvira” (1907), “Silvana Cenni” (1922), and “Le sorelle Pontorno” (1937).

The exhibition also emphasises Casorati’s connection to Milan, a city he considered strategically important for its vibrant art scene; Casorati’s multifaceted talent extended beyond painting; he was also a sculptor, graphic artist, and stage designer. His contributions to theatre are highlighted through sketches and designs for productions at venues like Teatro alla Scala.

1. From Padua to Naples: The Early Adventures

Felice Casorati may have started his artistic journey in 1904 at the Philharmonic Circle in Padua, but his real breakthrough came in 1907 at the Venice Biennale. There, as we have seen, he made waves with his evocative Portrait of Sister Elvira—a dreamy composition featuring a misty oval halo framing her face and a delicately gloved hand. It’s also the perfect ratio for an Instagram story, for some reason.

By 1909, Casorati had packed his bags and moved to Naples with his family. For that year’s Biennale, he upped the ante with The Old Women—a bold piece snapped up by the Italian government for Rome’s National Gallery of Modern Art. Critics were wowed by the “masterful composition,” rich colours, and emotionally intense portrayals of timeworn faces.

Casorati wasn’t just painting from imagination—he was strolling through museums to seek intellectual validation for his inspiration. His studies of the old masters at Capodimonte and the Uffizi clearly left their mark. In particular, Bruegel’s Parable of the Blind made an impression. You can catch nods to Botticelli, Velázquez, and Titian in later works like Children in the Meadow and The Heiresses.

But perhaps his most original piece from the Naples chapter is People, a cryptic and slightly surreal painting that feels like a poetic riddle. One critic described it beautifully as “the end of a meal of memories”—a perfect way to sum up Casorati’s early period: rich, layered, and lingering long after you’ve taken it in.

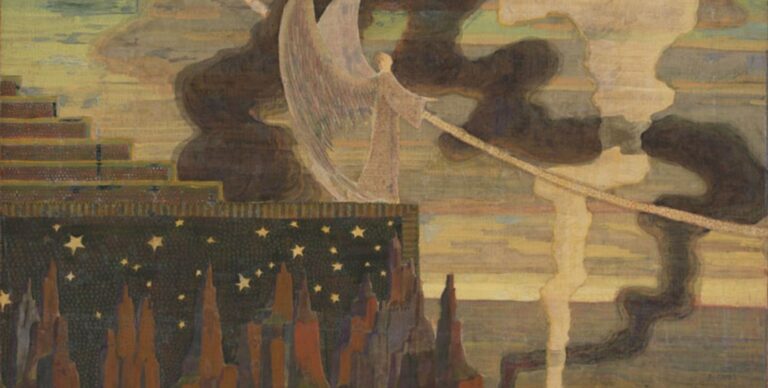

2. Allegories, Symbols, and a Dash of Drama: Casorati in Verona (1912–1914)

My personal favourite section of the exhibition covers the span of two years in which he was most influenced by Symbolism and other artists like Gustav Klimt.

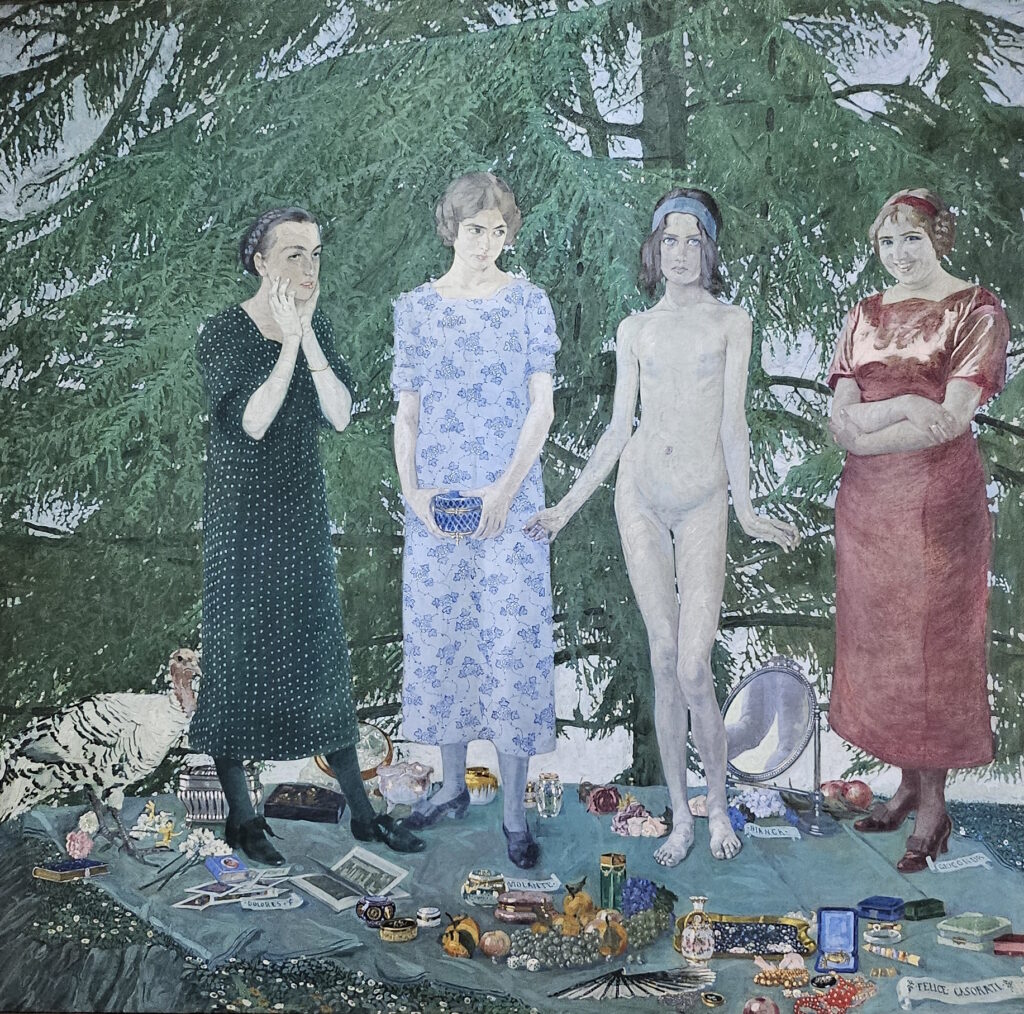

By 1912, Felice Casorati was no longer just “one to watch”—he was officially regarded as one of the most prominent artists of his time. His painting Signorine, fresh from its debut at the Venice Biennale, was scooped up by the International Gallery of Modern Art at Ca’ Pesaro in Venice. With this work, Casorati sealed his place as one of the key voices of European Symbolism.

Set against a leafy backdrop, Signorine channels major Primavera energy à la Botticelli. Four women appear, each with a dramatic persona straight out of a Renaissance mood board: Dolores, the personification of grief; Violante, steeped in melancholy; Bianca, radiating purity; and Gioconda, the happy housewife archetype, basking in matrimonial bliss. At their feet, a still life of jewels, mementoes and bourgeois tokens.

Casorati’s brush was clearly being guided by more than just the muses—enter Gustav Klimt. After being thoroughly wowed by Klimt’s work at the 1910 Biennale (where Casorati’s own work was prominently featured), our local painter took a stylistic leap. The result was a deep dive into dreamlike Symbolism with a Viennese twist I’m only sad it didn’t last longer.

Between 1913 and 1914, Casorati produced some of his most emotionally resonant pieces, such as Nocturne, Two Figures, and The Milky Way. These works reflect not only a surreal, almost magical atmosphere but also his bold experiments with form and design.

3. Grand Temperas and Quiet Drama: Casorati in Turin (1918–1920)

In 1918, still in Verona, Felice Casorati dove headfirst into what would become one of the most striking chapters of his career: the era of the grand temperas. This series kicked off with the ghostly portrait of Teresa Madinelli Veronesi, quickly followed by the quietly haunting The Waiting and the metaphysical vision of Maria Anna De Lisi in Girl with a Bowl. By 1919–1920, Casorati wrapped up the cycle with The Man with the Barrels and Morning.

These works—and those from the early 1920s—cemented Casorati’s signature style: instantly recognisable and now a favourite of critics and art collectors alike. What makes them so unforgettable are the desolate interiors, carefully staged as if to create a mental landscape rather than a physical space. The figures within are stripped of realistic detail, frozen in stylised poses and garments that feel more symbolic than specific.

The atmosphere is heavy with anticipation and anxiety. Everyone—and everything—seems to be waiting, stuck in a quiet emotional limbo. Even the mundane objects, like the bowl and cutlery in The Waiting, seem to be emotionally checked out, almost slipping out of the frame. In Maria Anna De Lisi, the iconic terracotta sculpture Head of Ada silently converses with the solemn, statuesque presence of the model, creating an eerie sense of suspended dialogue. And the exhibition pairs them masterfully.

Casorati’s temperas aren’t just paintings—they’re psychological spaces. Still, silent, and unsettling in the most beautiful way.

4. Masks, Armour, and a Touch of Rebellion: Casorati Between 1914–1921

A new era, which seems to be the natural development of both symbolism and the temperas’ anxiety, kicks off with the unexpected Joke: Marionettes in 1914. He began crafting what critics called “artificial still lifes”—not your average fruit bowls and flower vases, but staged objects with a conceptual edge. These works marked his deliberate break from Symbolism and decorative flourishes, aiming instead for a stripped-down, pure kind of painting.

What’s fascinating about this phase is its unsettling, playful spirit, like a horror house. You can see it clearly in Toys, one of the few paintings Casorati completed during World War I, and especially in the wildly provocative Target Practice. When he exhibited this work in Turin in 1919, it caused quite a stir. Some critics even accused him of dabbling in Futurism, scandalised by the almost abstract, distorted forms of carnival-style shooting range targets. It makes me laugh so much.

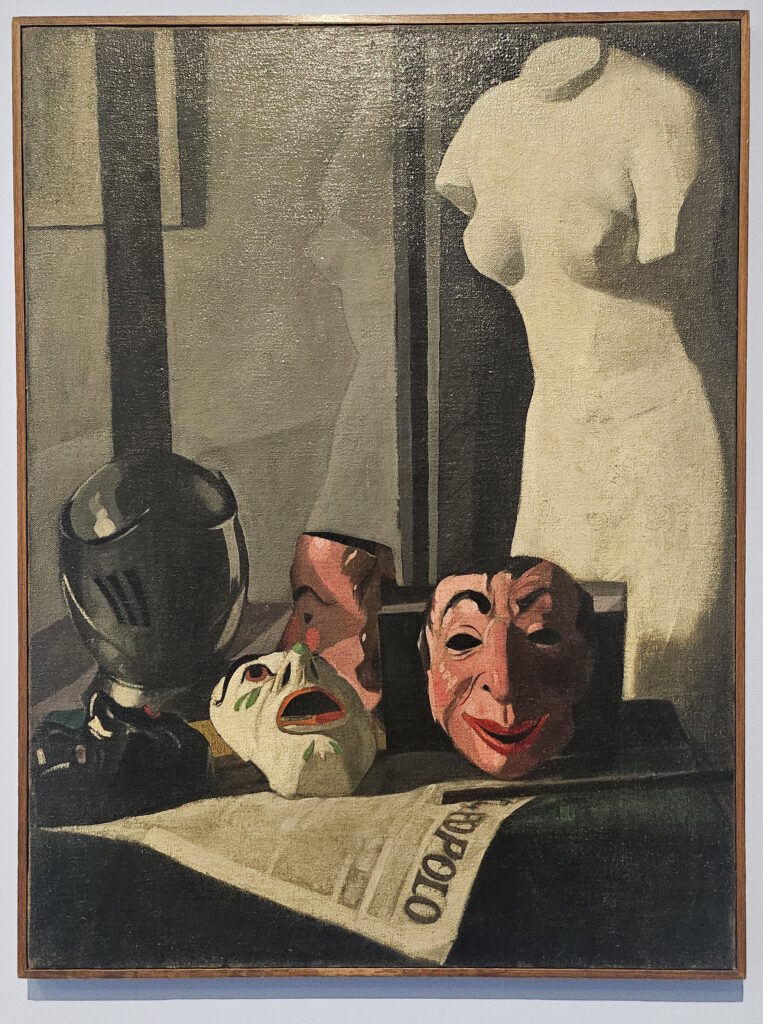

Then there’s Masks, a still life set in his studio that subtly introduces an unexpected guest: a helmet. This curious detail becomes a key motif in The Woman and the Armour, where it looms in the background, setting up a silent tension with the quietly introspective nude figure resting in the foreground.

This was Casorati in transformation—playful, provocative, and experimenting with visual language that left Symbolism behind, but carried its theatrical soul forward in entirely new ways.

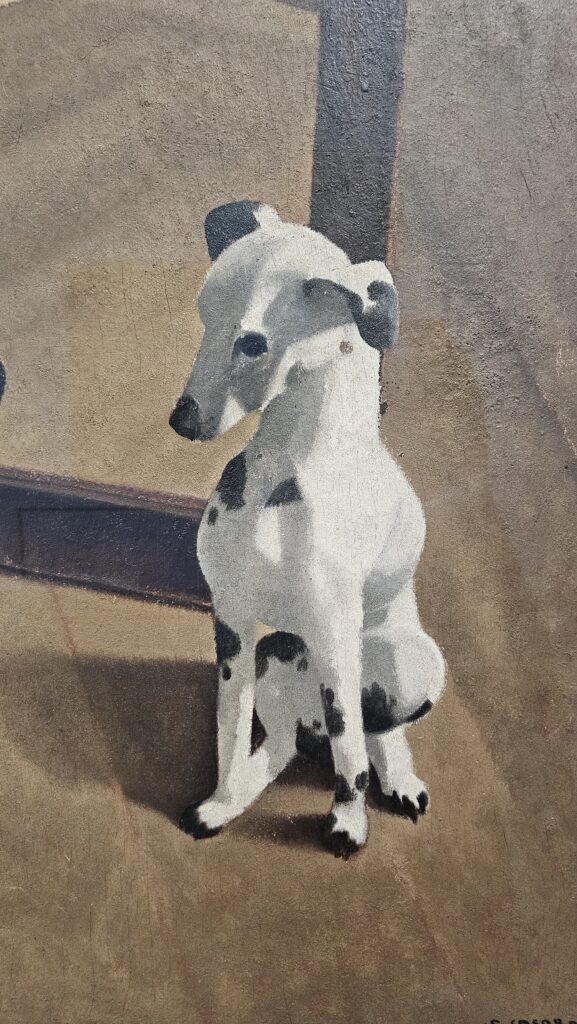

5. Silvana Cenni (1922): Eggs, Icons, and Imagined Saints

And now it’s time to talk about eggs. Yes, eggs. When Felice Casorati painted Eggs on the Drawer, critics like Piero Gobetti and Lionello Venturi were genuinely thrilled. Why? Because the piece was a breath of fresh air: perfectly composed, subtly colored (“humble hues,” as Venturi put it), and marked by forms that were both loved and familiar. It signalled what they called “a new light, anti-Impressionist” and a confident leap into a style all Casorati’s own.

There were whispers of Cézanne, of course—Casorati had admired his work at the 1920 Venice Biennale—but those enigmatic eggs carried a different weight. With their sculptural perfection, they seemed to echo Piero della Francesca’s sacred geometry, especially the Brera Altarpiece, where a single egg hangs as a mystical focal point.

Enter Silvana Cenni, perhaps Casorati’s most famous painting. This large-scale tempera work is both monumental and intimate—a reinterpretation of Renaissance Madonna imagery seen through a modern, deeply personal lens. Painted in 1922 and measuring 205 x 105 cm, it’s widely regarded as one of the artist’s most significant and enigmatic works. The portrait depicts a woman seated on a wooden chair draped with a damask cloth. She is dressed in white, with her hair neatly gathered, her eyes closed, and her arms resting on the chair’s back, hands relaxed and lowered. Around her are books, scrolls, and various objects, suggesting an intellectual or artistic environment. Behind her, through a window, one sees fields and the distinctive silhouette of a monastery with a portico and distant hills.

According to the curators, it draws directly from Della Francesca’s Polyptych of Mercy. I don’t see it, but I’ll let you be the judge of that.

Despite its religious air, Silvana Cenni is a fictional portrait. The name is made up. There’s no Silvana Cenni. There never were. But that only adds to the mystique. Casorati gives his imagined woman the gravitas of a literary heroine. She’s been called a “ghost woman”—seated like a statue, stiff yet serene, backed by a classical-style building reminiscent of Turin’s Church of Santa Maria del Monte on Cappuccini Hill. A Madonna, a phantom, or a timeless muse. Silvana Cenni stands as a symbol of Casorati’s unique vision: classical, modern, and unmistakably his.

6. A Private Stage and Public Style: Casorati & the Gualinos (1922–1926)

Between 1922 and 1926, Felice Casorati found himself at the heart of an artistic alliance with Riccardo and Cesarina Gualino—the power couple of cultural life in 1920s Turin. Patrons, collectors, and tastemakers, the Gualinos commissioned Casorati to capture their portraits in a Renaissance-inspired style, though dressed in chic modern garb. Classical poses with contemporary flair, we might say.

Casorati showed off these portraits at the 1923 Turin Quadrennial and again at the 1924 Venice Biennale, where he also unveiled a portrait of their son. These artworks reflected the luxurious aesthetic of the Gualinos’ Turin residence—an interior soaked in opulence, funded by Riccardo’s booming business empire.

But the real jewel of this collaboration was a private theatre, dreamed up by the Gualinos and entrusted to Casorati in 1924. Designed with architect Alberto Sartoris, the space was a minimalist marvel: black seating, grey walls, and pristine white bas-reliefs (three of which are on view in the exhibition).

The theatre wasn’t just for show. It hosted concerts, poetry readings, and modern dance performances, often led by Cesarina Gualino and the Markman sisters—who are themselves immortalised in one of Casorati’s tempera portraits, Raja. One notable figure who stepped onto that stage was composer Alfredo Casella, painted by Casorati in 1926, who conducted a concert dedicated to Igor Stravinsky.

7. Back at the Venice Biennale (1924): Light, Form, and a Lost Masterpiece

Casorati came back to Venice in 1924, with a personal exhibition at the Venice Biennale. Out of the fourteen works he showcased the first time, seven make a comeback in this current exhibition. Among them are portraits of the Gualino family, Meriggio, Double Portrait, Portrait of Hena Rigotti, and Mannequins.

A black-and-white photo from that Biennale also offers a tantalising glimpse of Studio, a now-lost masterpiece tragically destroyed in the 1931 fire at Munich’s Glass Palace. But even without it, the works from Venice reveal Casorati at a turning point—embracing tradition while boldly crafting his own language of form.

Among the most talked-about works in Venice was Portrait of Hena Rigotti, posed almost like a modern-day Virgin Mary. Casorati cleverly placed her against the familiar backdrop of his earlier Portrait of Maria Anna De Lisi from 1919, blending past and present. And then there’s Mannequins, where Casorati paints himself reflected in a mirror—one of his rare and nearly silent self-portraits.

The success of this 1924 solo show didn’t just boost his reputation in Italy. It catapulted Casorati into the international art scene, opening doors to exhibitions across Europe and the United States.

Influenced by the broader post-war return to order and craft, Casorati’s paintings from this period celebrate structure and classical sensibilities. Colour becomes a vehicle for light, and his brushwork takes on a polished smoothness. Flesh appears porcelain-like, dishes gleam with enamel sheen, and details like the soft hat and slippers in Meriggio add a tactile richness that became a hallmark of Casorati’s style.

8. Platonic Conversations (1925–1930): an accidental inspiration

Sometimes, great art begins by chance. That’s exactly how Felice Casorati described the birth of Platonic Conversation. One day, a friend stopped by his studio during a nude posing session. Casorati later recalled, “I don’t quite know what I felt, but I saw the painting—the painting I wanted to make.” It was a moment of serendipity: the sombre, modest figure of the man juxtaposed against the luminous, almost blindingly glazed surface of the woman’s body.

When Casorati exhibited the painting in 1926 at the First National Exhibition of 20th-Century Italian Art in Milan—curated by Margherita Sarfatti—it caught the critics’ attention. The two figures in the painting, posed together with a strange air of restrained sensuality, sparked a lively public debate in newspapers: was this an exploration of gender dynamics? A commentary on the relationship between men and women?

Between the first Platonic Conversation (1925) and the second (1929), Casorati’s work entered a new phase. He gradually moved away from classical formality—not through rebellion, but through a shift in his style and materials. His palette changed, as did his handling of paint, which became more opaque, even porous in texture. I strongly prefer the first (so much that I didn’t even take a picture of the second one).

This evolution is especially visible in Annunciation (a work recently brought back into public view) and Beethoven—two paintings that share the recurring motif of the mirror. During this period, Casorati also deepened his love for still lifes, a genre he described as offering “the most beautiful and most free architecture” for a painter to explore.

9. The Springtime of Painting (1927–1932): Light, Stillness, and Symbolic Fruit

Spring had a special meaning for Felice Casorati—not just as a season, but as a metaphor for artistic renewal. He even added “Primavera” to titles like April and Portrait of a Young Girl, as if to underline the warm, fresh air that his evolving style was starting to breathe.

By the time of the 1930 Venice Biennale, critics were recognising a “new Casorati.” His figures were now wrapped in soft atmospheric tones—not realistic, but radiant in a dreamy way. Set in calm domestic interiors, his characters were surrounded by familiar household items: a basin and mirror in April; a watering can, a mat, and a dish towel in Portrait of a Young Girl. These weren’t just background props—they were part of a quiet, staged intimacy.

Around this time, Casorati began expanding his visual vocabulary of femininity. He introduced a broader variety of female forms, moving between delicate, slender bodies and more statuesque, solid types, all rendered with elegant, almost sculptural distortion.

In Girls in Nervi, for instance, the woman on the right is a striking figure in a turquoise dress—regal, still, and monumental. This painting is many things at once: a figure composition, a seascape, and even a still life, with a tray of fruit prominently displayed in the foreground. The silent tension between the two girls plays out entirely in the expressive choreography of their hands.

One of Casorati’s most striking colourist achievements from this period comes in Apples (1932). These are no ordinary apples—they are luscious, red and green, nestled into folds of dusty pink fabric, transformed into near-mythical fruit, glowing like something from a fairy tale.

10. The Melancholic Figures (1931–1937): Stillness, Silence, and Emotional Gravity

There’s a quiet melancholy that lingers in many of Felice Casorati’s works from the 1930s. A mood of meditative stillness—tinged with vulnerability, introspection, and waiting—settles over his portraits of women and girls, whether clothed or nude. These are not dramatic scenes, but carefully crafted tensions between psychological depth and compositional restraint.

Take Woman with a Cloak, for instance: seated on a plain chair in a bare room, she folds in on herself, a figure of sorrow and solitude. Casorati painted her with a rare emotional intensity, capturing her as someone enclosed in her own world.

In Girl in Pavarolo (also known as Clelia), we meet a fragile young adolescent, bare-chested and seated with her hands in her lap. The soft greens and blues that bathe the scene lend it a tender, more bittersweet sense of melancholy—less stark, more dreamlike.

One of the most striking works of this phase is Woman at the Table, created in the mid-1930s. The composition unfolds on two levels: the figure in the foreground, and behind her, a still life of domestic objects laid out on a table. The woman herself, semi-nude, leans forward with her chest bare. One hand rests on her thigh, the other cradles her head, and her entire posture radiates a quiet yet theatrical sorrow. It’s a study in melancholic grace—where stillness becomes its own kind of drama.

11. Masterpieces of the 1930s (1933–1937): Serenity, Symbols, and Sisters

Among the standout works featured in Felice Casorati’s personal exhibition at the 1934 Venice Biennale were three major pieces described as true pièces de résistance: Daphne in Pavarolo and Women in a Boat. Out of the thirteen paintings he exhibited, these stood out for their beauty, symbolism, and quiet emotional power.

Daphne in Pavarolo is a portrait of calm and harmony. Casorati paints his wife Daphne seated on a windowsill, looking out over the soft, undulating hills of the countryside around their home. The scene is a symbol of his emotional peace and marks a shift in his painting—away from the formal confines of the studio and into the natural world beyond.

Women in a Boat is a more constructed and sculptural composition, shaped like a dreamy allegory of life itself. Set in a mythic, timeless space, the painting revolves around a woman nursing her child, bathed in a poetic, almost suspended atmosphere that feels part dream, part memory.

That same tender image—a mother nursing her child—reappears in The Pontorno Sisters, one of the defining masterpieces of Casorati’s late 1930s output. Presented at the 1938 Venice Biennale, the painting captures a scene of delicate domestic intimacy: sisters sharing a quiet moment in a simple room, filled with soft light and a peaceful, tonal calm.

These works show Casorati at his most emotionally resonant, merging myth, memory, and the everyday into something timeless.

12. The Enigma of Narcissus (1937–1944): Fragile Beauty and Silent Tension

From the late 1930s onward, Felice Casorati turned his gaze to more vulnerable subjects—specifically, young boys portrayed in their delicate, exposed nudity. One of the most poignant examples is the mysterious Narcissus, a loose evocation of the ancient myth. In this painting, a fragile, nude boy stands in the foreground, his eyes cast downward toward a mirror placed on the floor. This modern-day Narcissus, alone in a bare, desolate room, stands motionless in a posture that radiates sorrow and isolation. Behind him, two modestly dressed young girls linger in the background, their hesitant gestures suggesting an awareness of something tragic yet unspoken.

There’s an underlying tension in these scenes—a quiet, haunting unease shaped by the looming shadow of wartime. You feel it not only in Narcissus, but also in the subdued chromatic atmosphere of works like The Green Nude, where a young girl sits in a chair, and Two Women, where a wordless conversation unfolds between two female figures.

One of the most visually arresting pieces in this group is Back Nude, a large-format painting executed with refined elegance. The composition features a woman seen from behind, her long red hair cascading over her back. Her gracefully curved silhouette stands out in front of a softly lit windowed door, creating a powerful contrast of presence and absence, form and fading.

In these late works, Casorati blends myth, memory, and emotional fragility into a still, suspended world—one where the body becomes both subject and symbol.

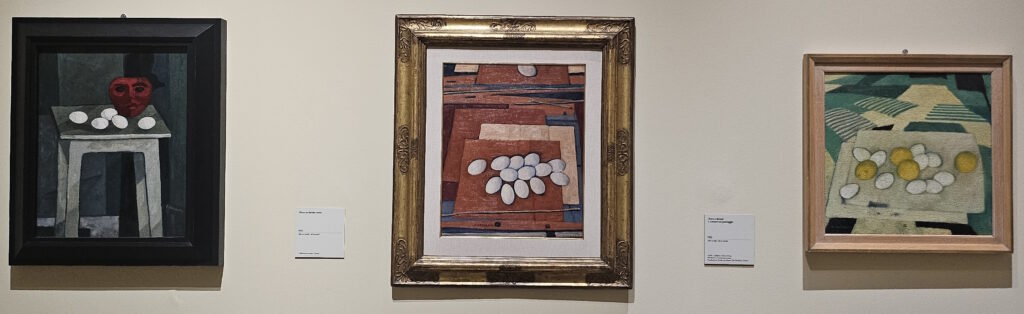

13. The Strategy of Composition: Still Lifes (1947–1953)

For Casorati, still life painting was never just about objects—it was a key laboratory for refining his compositional strategy throughout his career. In this genre, he achieved some of his most extraordinary results, using it to explore essential aspects of his aesthetic vision. Of particular interest for the show are the still lifes from the late 1940s and post-war period. Here, Casorati revisits his favourite themes, but with increasingly refined formal and chromatic solutions that gradually become more stylised and synthetic in appearance. There’s also a series of still lifes with strong symbolic resonance, which feature plaster casts (of feet, hands, arms, classical busts), mannequins, masks, and heads—recycled and reimagined from his earlier works. I love them to bits.

One especially inventive work is Paralleli—on the right in the picture above—where Casorati suggests the presence of a female figure using only fragments of plaster body parts placed on layered, stratified surfaces. In Eclipse of the Moon—above in the middle—he proposes what feels like a miniature theatrical set, with an astrolabe positioned at the center, flanked by two vertical panels that function almost like curtains on a stage. Then there’s Still Life with Helmet—on the left—a composition made of ovoid forms, where Casorati plays an elegant formal game with abstract undertones. The two eggs placed in the arrangement aren’t just decorative—they’re carefully chosen elements that carry symbolic and visual weight. Casorati sure loved his eggs.

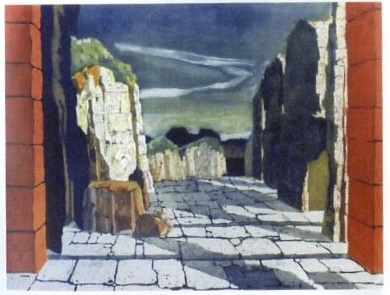

14. Casorati at La Scala (1947–1951): From Canvas to Stage

As we have seen with the theatre, Felice Casorati wasn’t only a master of the canvas—he had a spatial sensibility akin to an architect, and he brought that creative vision to the theatrical stage. His long-standing collaboration with Milan’s Teatro alla Scala began in 1942 with set designs and costume sketches for La donna serpente, a fantastical opera by Alfredo Casella.

Over the next decade, Casorati would design for seven more productions, a journey captured in this exhibition through a selection of his stunning scenic and costume work.

From La follia di Orlando, a ballet by Goffredo Petrassi, we see Casorati’s whimsical set sketches and costume designs for the characters Astolfo and Medoro—both full of imagination and flair. For The Bacchae by Giorgio Federico Ghedini, he reimagined the mythic drama in rich operatic tones, with classical stage structures reminiscent of regal architecture.

And finally, for Bartók’s The Wooden Prince, Casorati fully embraced fantasy. His dreamlike sets are straight out of a fairy tale, complete with enchanted forests and pointed castle towers rising from the stage like something out of a storybook. Through his work at La Scala, Casorati brought the same sensitivity, structure, and elegance that defined his paintings into the realm of performance, crafting entire worlds for opera and ballet.

No Comments