I know I’m overdue two important posts, one on the Biennale in Venice and one on the Triennale here in Milan, but I’m still digesting many of the things I saw over there. More importantly, I’m working around the concept of adaptive and responsive architecture for an upcoming paper, so I thought I’d share some notes with you. They dive back into 2019, when Carlo Ratti & gang went to Asia with some inputs that resonate hard with this year’s Biennale. So here they are.

From Shenzhen to Venice: the Eyes of the City and the Evolution of Urban Gaze

Since its inception, the Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (UABB) has stood as one of the most forward-looking international platforms for architectural experimentation in urban contexts, with a dual-city structure shared between Shenzhen and Hong Kong. The 2019 edition, hosted in Shenzhen’s Futian high-speed railway station, took the theme of “Urban Interactions”, situating architecture not as a mere container of social life but as an interface reshaped by digital, mobile, and automated forces.

The year 2019 was distinctive for the explicit confrontation between spatial design and emerging technologies, with a focus on how architecture could evolve when cities themselves become sentient, data-rich entities. In this context, the “Eyes of the City” section — one of the Biennale’s main curatorial frameworks — offered a particularly thought-provoking lens into the dilemmas and potentials of digitally augmented environments. The catalogue can still be downloaded for free on the exhibition’s website.

“Eyes of the City”: A Curatorial Framework

Curated by Carlo Ratti, Michele Bonino, and Sun Yimin, the “Eyes of the City” exhibition was premised on a single powerful question: how does architecture change when every space becomes able to see by itself?

The title alludes to a condition in which buildings, infrastructures, and even urban voids are embedded with sensorial and computational capacities — especially facial recognition and AI-driven analytics — that allow them to observe, interpret, and respond to the presence of human and non-human agents. In this “aware city“, the architectural envelope is no longer passive but active, capable of modulation and reaction.

The choice of a functioning transportation node — Futian Railway Station — as the exhibition venue was not accidental. It served as both a site of transit and surveillance, exemplifying the dynamics of contemporary mobility and its coupling with biometric tracking systems. Rather than creating a neutral gallery space, the curators embedded the works within the operational logic of the station, allowing interventions to become part of the everyday experience and flows.

Contributions and Themes

The “Eyes of the City” section featured over 60 contributors from architectural firms, technology developers, academic institutions, and speculative designers. While their approaches differed, several thematic strands emerged:

- Facial recognition and privacy: projects challenged the opaque logic of biometric surveillance, often proposing counter-measures or speculative scenarios of resistance.

- Urban intelligence and adaptation: several contributors examined how AI can be integrated into the city to enhance responsiveness, including through real-time environmental modulation or anticipatory design.

- Architecture of presence: the notion of presence itself was questioned—what does it mean to be “seen” by architecture? Can architecture prioritise agency without reducing humans to data points?

- Alternative ontologies: designers like Liam Young, Philip Beesley, and others presented architectures not as inert spaces, but as symbiotic, soft, and partially autonomous agents in their own right.

The catalogue frames these projects within a broader reconsideration of spatial authorship: where before architecture spoke for the city, now it may begin to speak with the city, in an entangled dialogue of code, form, and social feedback.

Why talk about it now?

Carlo Ratti’s role as curator of the Venice Biennale 2025 — six whole years after “Eyes of the City” — offers a compelling thread of continuity. While details of the upcoming Biennale are still emerging, Ratti’s long-standing interest in responsive environments, civic sensing, and architectural intelligence suggests that Venice 2025 represents a theoretical maturation of many of the ideas first tested in Shenzhen.

Indeed, Shenzhen served as a test-bed for future urbanity, especially in how architectural intelligence intersects with ethics, politics, and the aesthetics of transparency. Venice, by contrast, may serve as a stage for more reflective, institutional, and globally situated debates, especially in light of Europe’s intensifying conversations on privacy, regulation, and technological sovereignty.

So, here are my notes. Were you lucky enough to see the exhibition? Did you read the book? Lay your insights on us.

Focus 1: Digital Societies

Camilla Forina, from Turin’s Politecnico, curates the theoretical backbone to this section in the corresponding publication, Architecture and Urban Space After Artificial Intelligence, published in 2021 as the result of the works in Shenzhen. A few copies of the book were still available at the Biennale’s bookstore when I went there.

“New technologies are redefining the notion of citizenship. How can we interpret the ‘eyes of the city’ idea from this perspective? This section revolved around the interaction between people, technology, and space. From observing what can be achieved when data is used to better understand society to using virtual platforms as spaces to collect people’s input, this section explored new ways in which inhabitants can get involved in the making of the city.”

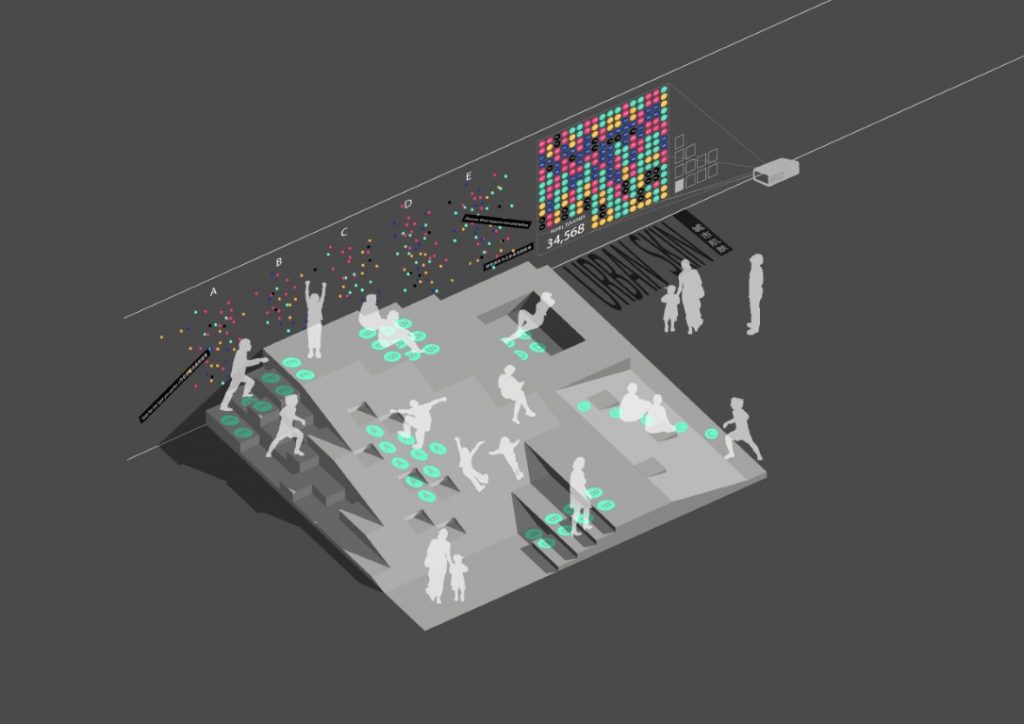

Palimpsest Shenzhen: rewriting the Urban Script Through Participatory Foresight

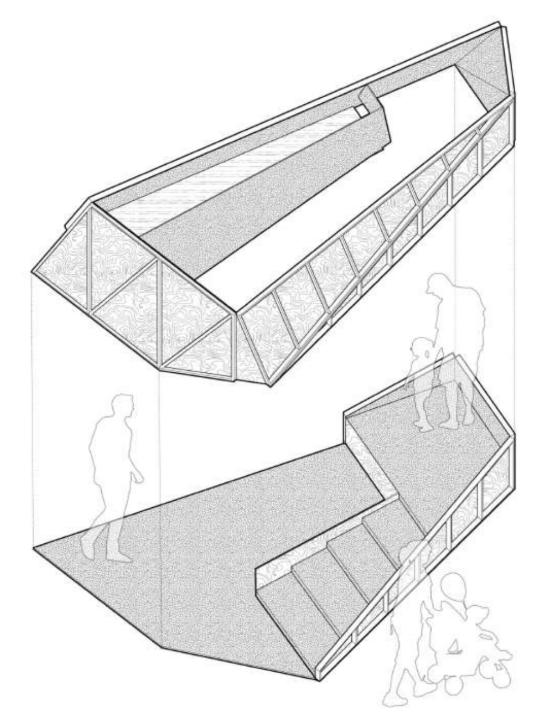

Among the most conceptually layered and architecturally suggestive contributions to the Digital Societies section of the 2019 Eyes of the City exhibition, Palimpsest Shenzhen by Wee Studio proposed a critical rethinking of how urban futures can be collectively imagined, authored, and materialised. Conceived as a participatory installation embedded directly within the exhibition floor, the project took the form of a large black case — at once object and interface — inviting visitors to input their aspirations, concerns, and priorities regarding the urban development of Shenzhen. Through a hybrid of analogue and digital media, it staged a kind of urban theatre of decision-making, where each action performed within the installation generated an evolving “crowdfunding strategy” for city-making. This speculative platform was not limited to representation: it modelled an architecture of active engagement, where the typical opacity of development processes was dissolved into a public choreography of data, desire, and democratic imagination.

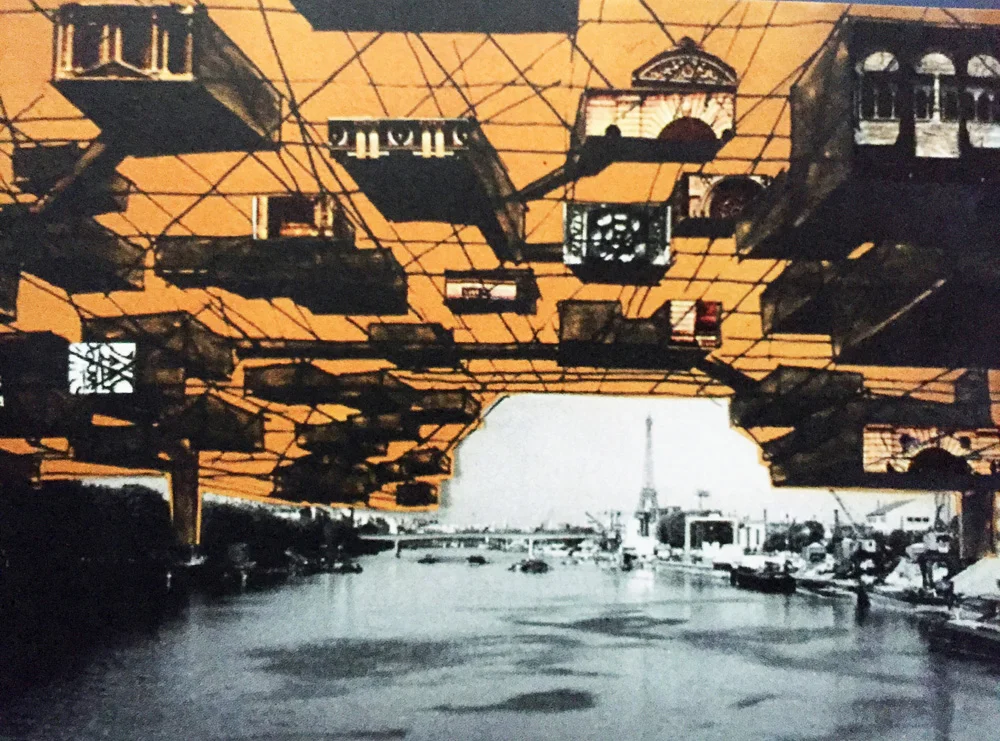

Wee Studio, in a design-research approach at the intersection of urban culture, technology, and participatory policy, structured the installation as a socio-political simulator. Participants were stakeholders in a scenario that, while fictional, drew on real geographic and sociopolitical data. In doing so, Palimpsest Shenzhen echoed both contemporary urban games such as Parsons’ “The Urbano Project” or MIT Media Lab’s CityScope, and historical precedents such as Yona Friedman’s “Ville Spatiale”, Cedric Price’s “Fun Palace”, or even the Delphi participatory planning experiments of the 1970s. Like these, it postulated architecture as a framework for negotiation, not a fixed product but a canvas for collective rewriting.

The use of the term “palimpsest” is critical here: rather than proposing tabula rasa interventions, the project conceptualised the city as a stratified space of successive inscriptions, where each new layer of design is aware of, but not necessarily constrained by, the past. In this sense, the installation resonated with Rem Koolhaas’ reflections on Lagos as a city of “residual structures” and with Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman’s civic platforms for participatory urbanism. Palimpsest Shenzhen brought these concerns into the computational age: its material interface recorded inputs via sensors and interactive mapping tools, simulating how citizen-driven data might inform future governance and spatial planning.

Importantly, its inclusion in the Eyes of the City exhibition positioned it within a broader inquiry into how architecture sees, remembers, and acts. In contrast to projects that embedded surveillance as a mode of control or visibility, this installation proposed a reverse gaze: it asked what a city might become if it could be seen through the collective eyes of its inhabitants. In doing so, it offered a counterpoint to more techno-deterministic installations by leveraging the same technologies (sensors, data visualisation, crowd interfaces) in the service of civic agency, not extraction.

The implications of Palimpsest Shenzhen extend beyond Shenzhen. It can be read as a prototype for post-platform urbanism, where algorithmic governance and grassroots intelligence converge in a single design apparatus. In a time when smart city rhetoric often sidelines the messiness of public life, this installation reclaimed the idea that cities are not only data-rich environments but narrative-rich systems, always in the process of being collectively rewritten.

Focus 2: Design Intelligence

In the book, this section is expanded and commented by Valeria Federighi, also from Turin’s Politecnico, and investigates the integration of digital technologies into architectural design processes. It poses fundamental questions about how machines and AI-driven systems should behave in built environments, and how buildings might respond intelligently to their occupants. Far from a techno-utopian celebration, the section critically explores how architecture is transforming at the convergence of human judgment, algorithmic logic, and automated processes. The aim is not only to understand how these technologies operate but to question how they alter architectural agency, authorship, and the cultural processes of design.

The latest advances in Artificial Intelligence pose many ethical questions. How should machines behave? How should buildings imbued with Artificial Intelligence respond to their occupants? This section explores how the quintessential human prerogatives of “téchne” and “logos” can be hybridised with automatisms and algorithms. Ultimately, it showcases how new technologies are reshaping the ways in which we plan, design and build our cities, and new practices are emerging at the intersection of “bits and atoms”.

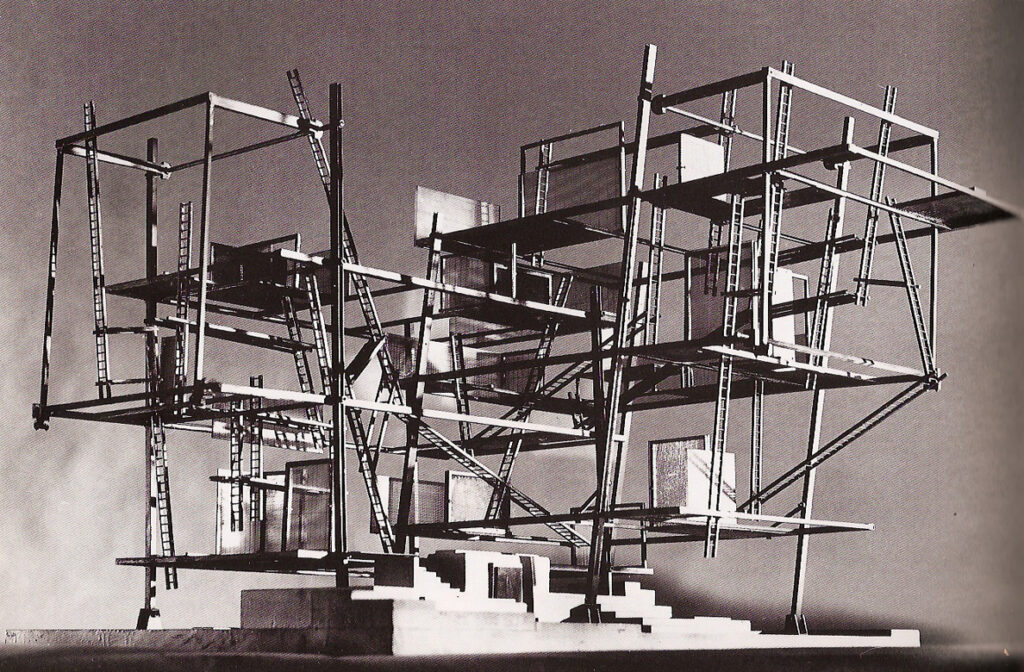

Urban Skin: towards a Sentient Architecture of Presence

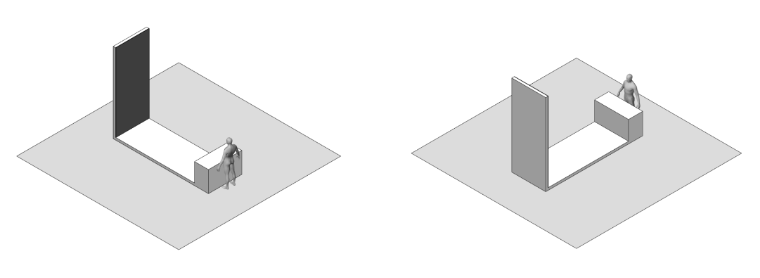

In Urban Skin, the collaborative work of Li Zhang, Marta Mancini, and Huishu Deng, architecture becomes an interface — at once tangible and intangible — through which the body and the city converse. The installation presented an experimental platform of responsive surfaces, modulated through sensors that capture the intensity and frequency of bodily presence. What emerges is not merely an artifice reacting to stimuli, but a provocative proposition for a new typology: one where architecture listens first, and only then expresses itself.

The system does not imitate traditional kinetic or interactive design, but it composes a soft prosthetic for public space, built from the ephemeral human interactions. The project functions on the edge of perceptibility, registering and amplifying minor shifts in bodily motion and atmospheric conditions. Rather than projecting form or space, Urban Skin yields an ambient intelligence, embedded in the fabric of architecture itself.

This approach echoes early speculative work in responsive environments — again from Cedric Price’s Fun Palace to Nicolas Negroponte’s Soft Architecture Machines — but repositions them within the contemporary logic of embedded AI, edge computing, and ubiquitous sensing. Unlike earlier analogue or centralised cybernetic systems, Urban Skin thrives on decentralisation: the computation is subtle, nearly invisible, and distributed. The project eschews spectacle in favour of phenomenological nuance, inviting a closer look into how data might not only inform design but also become its material.

Urban Skin is best understood as part of a lineage of experiments on cybernetic architecture and performative environments, drawing from mid-century explorations such as Gordon Pask’s Colloquy of Mobiles (1968), while sharply diverging from them in ethos. Rather than producing feedback loops for machine learning alone, the installation restores the primacy of the user’s embodied experience, constructing what might be called an affective interface—one where the physical response of the architecture is modulated not by explicit commands, but by presence, duration, and relationality. In doing so, Urban Skin aligns with contemporary architectural theories of relational aesthetics and new materialism, where space is understood as an emergent, co-constituted field, shaped in real time by human and nonhuman agents. It builds on recent experiments by practices like Philip Beesley’s Hylozoic Ground or the Aegis Hyposurface by dECOi, yet narrows its scope: less operatic and more intimate.

One of the most critical dimensions of Urban Skin lies in its implicit rethinking of authorship. The system does not respond to pre-coded variables or programmable thresholds alone, but rather is co-constructed by its inhabitants, whose behaviour dynamically adjusts the parameters through which the installation calibrates itself. This is no longer the territory of architecture as an object, but of architecture as a negotiated field, an ecology of inputs and outputs continually being rewritten. From this standpoint, Urban Skin can be interpreted as an architectural argument rather than an architectural product: it suggests a shift from designing for users to designing with their ephemeral traces, challenging traditional binaries between subject and object, body and building, author and inhabitant.

The project points toward larger questions around urban interfaces, smart infrastructures, and the ethics of environmental data capture. How might buildings anticipate use without surveilling behaviour? How can responsive systems respect the unpredictability and dignity of human presence, rather than converting it into a set of extractable metrics?

In this regard, Urban Skin also stands in critical dialogue with other works in the same section, including AI-chitect’s exploration of generative design via neural networks, or Nomadic Wood’s robotic negotiation of tectonics. Yet while those works foreground the power of automation and machine logic, Urban Skin emphasises situated intelligence, not an all-knowing architecture, but an attuned one. It is less about prediction, and more about resonance. What is ultimately proposed is not a tool, nor even a system, but a prototype for spatial empathy. In an era where urbanism is increasingly shaped by metrics, sensors, and computation, Urban Skin reclaims the uncertain, the proximate, and the lived, offering a skin that does not just cover space, but feels it.

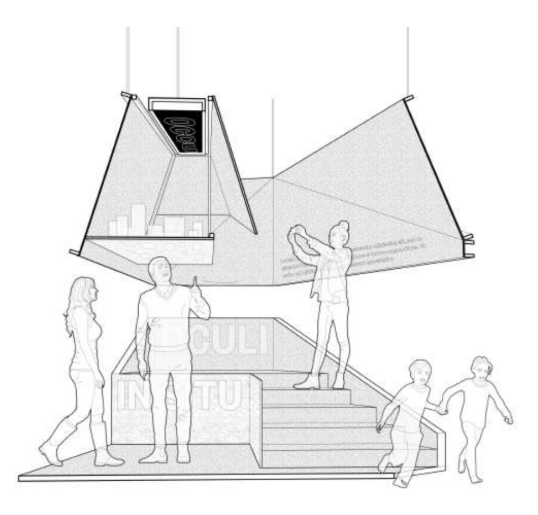

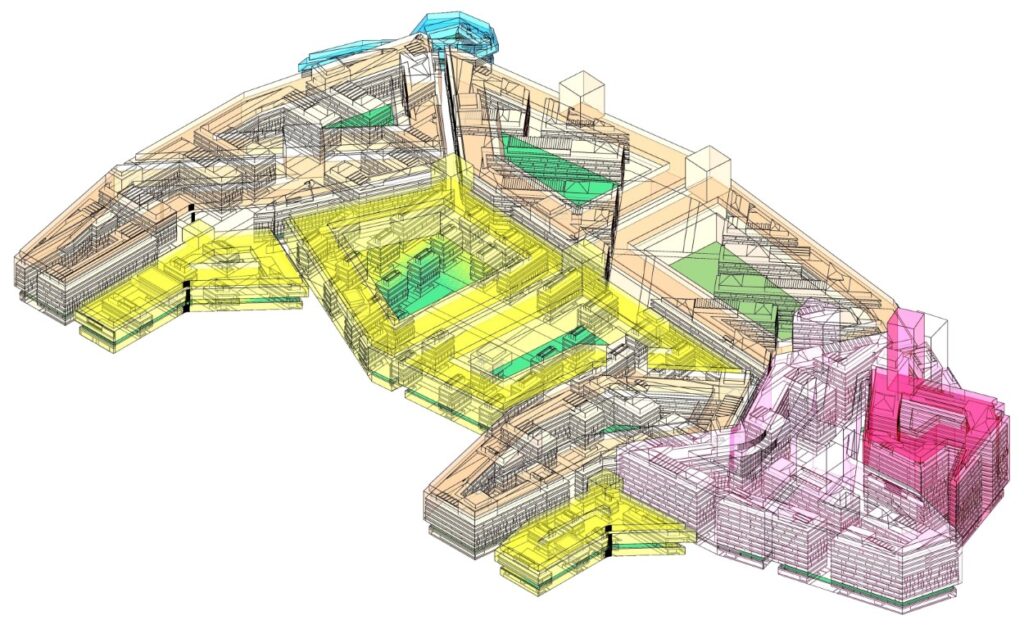

Everyone Is an Urbanist with CIIM!: Gaming the City, Designing Together

In Everyone Is an Urbanist with CIIM!, the boundaries between expert knowledge and civic participation, between design simulation and social negotiation, are deliberately blurred. Conceived by Weiwen Huang and Xue Chen at the Future Plus Academy, the project merges urban modelling, gamification, and public interaction through an innovative platform built around CIIM, a parametric design system adapted to the urban scale and participatory logic. What the installation offers is not simply a visualisation tool, but a new grammar of urban engagement, where the city becomes a shared interface and design becomes a game of civic intelligence.

At the heart of the project lies a playful but structured mechanism: visitors are invited to interact with the city through an intuitive game-based environment, in which adjustable parameters — density, program, mobility, form — become the levers of co-authorship. The goal is not to arrive at a final design solution, but to negotiate trade-offs, simulate the complexity of planning choices, and reflect on the cascading effects of urban form. In doing so, CIIM challenges both the authority of top-down planning and the presumed expertise of algorithmic optimisation. Instead, it enacts an agonistic, iterative form of planning, foregrounding the messiness and value of public input.

The project aligns with broader movements in civic tech and participatory design, yet its key innovation is to frame design as an accessible epistemology, one that doesn’t require professional fluency to navigate. CIIM is a modelling engine, but also an urban storytelling platform, where inhabitants, stakeholders, and non-specialists engage in a form of situated decision-making. In doing so, the project recalls the experimental ethos of Constant’s New Babylon — where the city was conceived as a field of collective authorship — and pairs it with the computational finesse of parametric platforms. CIIM’s visual language and system logic also resonate with projects like MIT’s CityScope or UNStudio’s Knowledge Models, yet it takes a more populist route. Its game-based interaction borrows from the UX principles of video games and participatory simulations, tapping into the cognitive grammar of gaming to create a non-threatening, low-barrier entry point into complex urban problems. Here, design is no longer the work of drafting a plan; it is the act of playing a meaningful role in the rules and consequences of city-making.

What sets Everyone Is an Urbanist with CIIM! apart from typical consultation platforms is its embedded design agency. Participants become co-authors of morphogenetic possibilities. Every action — every toggled parameter or placed structure — translates into real-time urban consequences, immediately visible and modifiable. The interface becomes a mirror of collective values, preferences, and conflicts. This deeply interactive approach confronts the limitations of “tokenistic participation” so often found in urban planning. It offers instead a sandbox of agency, where decisions can be rehearsed, undone, or reconfigured. In this sense, CIIM is less about predicting urban futures, and more about opening up design space for deliberative futures, those forged not by certainty, but by dialogue.

CIIM also serves an educational role: it demystifies urban complexity by making visible the systemic consequences of seemingly simple design moves. It turns urban form into a set of knowable and navigable relationships, a key step toward cultivating urban literacy in an increasingly technocratic landscape. This connects the project with the broader goals of “Design Intelligence” explored in Eyes of the City, where new technologies are deployed not to replace human designers, but to expand the field of contributors to the architectural process. Its implications stretch beyond the walls of the biennale. As a prototype for planning tools in democratic societies, it opens up possibilities for participatory zoning, community-driven infrastructure, and responsive urban scenarios where public values are not post-rationalised, but pre-inscribed into the act of shaping space.

In a world where cities are increasingly governed by data, metrics, and platforms, CIIM proposes a reversal: it leverages computation not for surveillance or optimization, but for distributed authorship and civic empowerment. Rather than flattening the city into a system to be managed, it renders it again as a site of choice, difference, and speculation. The installation speaks not only to the city of Shenzhen — a city shaped by speed, negotiation, and multiplicity — but to global contexts where urban agency is in crisis. CIIM doesn’t pretend to resolve that crisis. It instead opens a space where design becomes a shared game, and urban futures are constructed not from consensus, but from constructive conflict.

No Comments