Un film che comincia con Derek Jacobi non può che essere un buon film. Un film in costume, poi, che cominci con Derek Jacobi in abiti civili… beh, in passato era stato un film della madonna, il primo di una lunga serie di film che – dalle stelle alle stalle è proprio il caso di dirlo – ci ha condotti per mano da Molto Rumore per Nulla ad Amleto a Pene d’amor perdute a Come vi piace fino a… beh, fino a Thor. Ma questa è un’altra sordida faccenda e all’epoca di Enrico V, con la cui citazione abbastanza esplicita si apre questo film, non ne avevamo il sospetto.

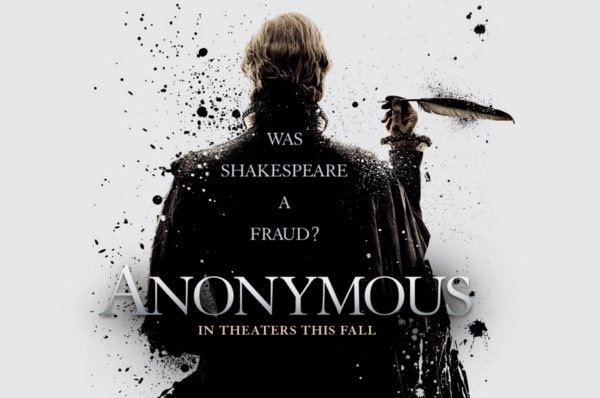

Questo film, dicevo, si apre con un’opera di meta-cinema e meta-teatro affatto ignota a Shakespeare stesso, e per qualche motivo piuttosto amata da un certo tipo di cinema in costume, se qualcuno si ricorda di Cantando dietro i paraventi (l’ultimo film degno di Ermanno Olmi che si preoccupasse di raccontare una storia e, per quanto mi riguarda, anche il primo) o se qualcuno ha affrontato con successo la visione di Nightwatching, il film sulla Ronda di notte di Rembrandt firmato da Peter Greenway. Un attore, un attore che arriva in taxi ed entra in scena, iniziando a recitare il prologo del film, un altro attore dietro di lui, in costume, che aspetta di entrare, ed una scena che si trasforma nelle strade notturne e piovose di Londra. Un ulteriore flash-back. L’inizio della vicenda. Questo film sin dall’inizio non si presenta come un prodotto dalla tessitura piatta anche se, come qualcuno potrebbe dire, altro non è che l’ennesimo film su Shakespeare e, di più, l’ennesima elucubrazione sulla reale identità di Shakespeare. Chi era in realtà il più celebre drammaturgo d’Inghilterra? Possibile che fosse veramente il figlio di un artigiano semi-illetterato di un paesino sperduto? Secondo molti no, secondo molti la sua prosa e i suoi riferimenti, sia culturali che sociali, sono il prodotto di una mente colta, che avesse viaggiato, ed ecco che William Shakespeare diventa un fantoccio, un prestanome per… per chi? Per un nobiluomo che con il suo nome non avrebbe potuto scrivere, e che attraverso le sue opere ha tentato di rovesciare le sorti della successione al trono d’Inghilterra.

Nel ruolo del suddetto nobiluomo, un ruolo che per qualche motivo pareva di nuovo perfetto per Joseph Fiennes, si muove egregiamente il gallese Rhys Ifans, appena uscito dal ruolo dello schizzato Xenophilus Lovegood in Harry Potter e i doni della morte, e lo affianca una ahimé non eccezionale Vanessa Redgrave nei panni di Elisabetta. Siamo negli anni finali del suo regno, quando già si parla della successione di James, ma – di flash-back in flash-back – ecco rovesciarsi le sorti, con un’eccellente e splendida Joely Richardson nei panni della giovane regina e un francamente ingessato Jamie Campbell Bower a sostituire Ifans come sua giovane controparte. Tra i nomi noti, troviamo naturalmente Ben Jonson, tra i protagonisti della vicenda, qui interpretato da quel Sebastian Armesto che ha un passato di re (Ferdinando VI in Pirati dei Caraibi e Carlo V nella prima stagione dei Tudors). E, ovviamente, lo spione Christopher Marlowe, interpretato da un d’artagnanesco Trystan Gravelle. William Shakespeare, uno spaccone di provincia, è invece affidato a Rafe Spall, che già s’era visto a vestire i panni dello schizzatissimo William Hunt di Desperate Romantics.

Tra i volti noti invece, oltre alle già citate due Elisabette, il Lupin di Harry Potter (David Thewlis, qui nei panni dell’oscuro consigliere della regina), Robert Emms (appena visto nell’inizio di Mirror Mirror che… lasciamo perdere) e Mark Ryland (l’inutile padre di The Other Boleyn Girl).

Per chi non è disposto a farsi spaventare dal fatto che metà del cast viene da Twilight, o per chi è disposto a dimenticare che in fondo è un film di Roland Emmerich, un thriller in costume con un ottimo ritmo, un’eccellente tessitura del soggetto e una splendida atmosfera.

Werewolves Wednesday: The Wolf-Leader (22)

A werewolf story by Alexandre Dumas père. Chapter XXII: Thibault’s Last Wish Urged in her flight by a hideous terror, and anxious to reach the village where she had left her husband with all speed possible, Agnelette, for the very reason that she was running so hastily,

No Comments