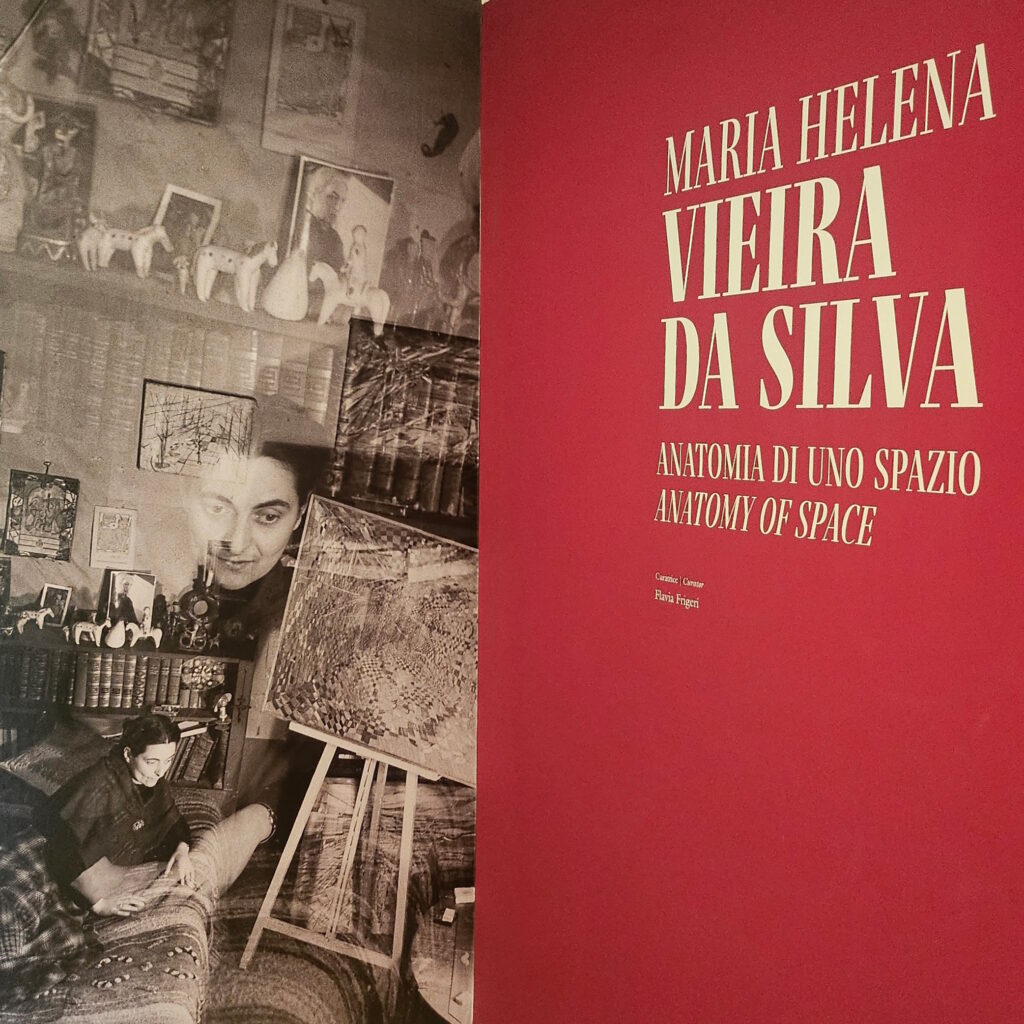

From April 12 to September 15, 2025, Venice’s Peggy Guggenheim Collection hosts the richly evocative solo exhibition Maria Helena Vieira da Silva: Anatomy of Space (Anatomia di uno spazio in Italian), curated by Flavia Frigeri, an art historian from London’s National Portrait Gallery. Featuring around seventy major works on loan from prestigious institutions such as the Centre Pompidou, Guggenheim New York, MoMA, the Tate Modern, and prominent private galleries, this exhibition offers an in-depth exploration of Vieira da Silva’s visual vocabulary.

A Portuguese-born artist who made Paris her artistic base, Vieira da Silva (Lisbona, 1908 – Parigi, 1992) became renowned for her innovative manipulation of pictorial space, melding abstraction with figuration to create labyrinthine, spatial illusions. Her work is richly infused with diverse influences: from Portuguese decorative traditions and urban landscapes to avant-garde movements like Cubism and Futurism. The exhibition traces her journey from the 1930s through the 1980s, spotlighting key periods including her formative years in Paris and her wartime exile in Rio de Janeiro alongside her husband, fellow artist Árpád Szenès.

Significantly, Vieira da Silva holds a longstanding connection to Peggy Guggenheim herself: she was one of the thirty-one women featured in Guggenheim’s groundbreaking 1943 show Exhibition by 31 Women at Art of This Century in New York, and earlier in 1937, Hilla Rebay (the Guggenheim Museum’s founding director) acquired her work Composition (1936), now in the Guggenheim’s permanent collection. Upon closing in Venice, the show will travel to the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao in autumn 2025.

This presentation, ambitious in scope and richly curated, illuminates Vieira da Silva’s enduring legacy: her ability to conjure immersive, abstracted realms where memory, architecture, and emotion converge. It invites viewers to consider space not merely as backdrop, but as the very subject of her artistry, a dynamic, living element testifying to the penetrating vision of a truly modern master. Let’s see what it’s about.

1. Painting Space: the Intimate Geometry of Vieira da Silva

“I love painting space.” With this simple yet profound declaration, Maria Helena Vieira da Silva invites us into the heart of her artistic vision: a lifelong, passionate pursuit of the intangible; space in all its guises, real and imagined. For her, painting space was not a matter of perspective or geometry alone, but of emotion, intuition, and memory. Two formative encounters in her youth — seemingly incidental, but in hindsight almost prophetic — set the foundation for this obsession.

The first came in 1926, in Lisbon, where a teenage Vieira da Silva enrolled in an anatomy course at the Escola de Belas Artes. There, she found herself mesmerised not by the figure as a whole, but by its inner scaffolding. “I drew hundreds,” she later recalled of her studies of the human skeleton. These were not dry academic sketches, but the beginning of a deeper fascination with structure—an interest that would eventually migrate from bone to architecture, from body to space. Works like Composition (1936) and The Weavers (1936) aren’t just experiments in abstraction; they are meditations on the skeleton of space itself. She speaks of her paintings as if navigating unknown terrain: “I walk through spaces where I’ve never known how to see, and which I am building as I go.” To look at them is to peer into a space mid-construction, at once delicate and determined.

The second revelation occurred in 1931, in Marseille, beneath an iron bridge in the old port. There, amidst the interplay of steel and sea breeze, Vieira da Silva experienced a revelation: space could flow. It could be as elusive as light, as ephemeral as a breeze. The encounter inspired her painting The Bridge in Marseille (1931), a work that captures not just the physical structure, but the shimmering weightlessness of air suspended between beams. It’s not just a bridge: it’s a metaphor for suspension, for transition, for the spaces that connect more than they separate.

These experiences — anatomy and architecture, bone and bridge — crystallised a unique way of seeing. Vieira da Silva didn’t depict space. She dissected it. She reimagined it as a living organism: a place of passage, of construction, of interiority. Her art was never content to merely reproduce the visible world. Instead, it asked: how do we feel space? How do we move through it, get lost in it, or — perhaps most radically — build it with our own eyes?

In the first room, we begin to understand Vieira da Silva not only as a painter of spaces but as an architect of the invisible, a cartographer of the mind’s eye.

2. Checkmate: Dancers, Chess Players, and Card Games

In one of the most perceptive readings of Maria Helena Vieira da Silva’s work, the Belgian critic and painter Michel Seuphor described her canvases as “spaces without dimensions that are at once finite and infinite, hallucinatory mosaics where each element contains an inner force that immediately transcends its own substance.” Nowhere does this paradox sing more clearly than in the works gathered in the second room: vibrant scenes populated by dancers, chess players, and figures immersed in card games, their gestures half-hidden within webs of painted squares. Possibly my favourite section.

At first glance, it all appears decorative: a kaleidoscope of tiny adjacent tiles, lovingly rendered with obsessive care. But let your eyes adjust to the logic of this language, and motion begins to emerge. Vieira da Silva builds her worlds out of countless interlocking squares: minuscule gestures that, when layered, shimmer with life. The colour palette is playful and dense: reds, greens, inky blues, and muted whites pulse like the tesserae of ancient mosaics or the hand-painted tiles of Lisbon’s azulejos. But here, they dance.

In Dance (1938) and Ballet of the Architects (1946), the dancers don’t move through space: they are the space. Their limbs merge with the planes around them, as if they were being folded into a breathing architecture. Each brushstroke flattens and deepens, like ripples meeting across the surface of a tiled fountain. Nothing is static. These paintings don’t depict scenes; they stage sensations. The ground becomes a tide. Walls sway. Figures flicker in and out of focus.

And then come the chessboards. Here, Vieira da Silva builds allegories for strategy, conflict, repetition. The players are locked into patterns, bound by a logic both orderly and mysterious. Each move echoes a decision made in the painting’s very structure. Cards are drawn. Pieces are pushed. The game, like the composition, is in a state of perpetual becoming.

In a rare personal insight, Vieira da Silva once explained that she preferred painting on large canvases using thin brushes, an approach she likened to tilework, embroidery, and even lace-making. This meticulous slowness gave her the rhythm she needed: “that rhythm,” she said, “is what gives life to what I seek. It allows me to find the heartbeat of a painting.”

3. The Second World War, seen from Rio de Janeiro

“I was afraid to stay in France after war was declared… I was panicking at the thought they might arrest Árpád.” With these words, Vieira da Silva distilled the terror that took hold of her life in 1939: the anxiety born of her Jewish husband’s background, of her own uncertain national identity, and of the rising shadow of persecution. When war erupted, she and Árpád Szenes left Paris and returned to Lisbon, hoping to reclaim Portuguese citizenship (lost after her marriage) and to avoid the growing danger. But their efforts to secure safety in Europe failed, and in June 1940, they boarded a ship bound for Rio de Janeiro.

What followed was anything but a tropical idyll. For Vieira da Silva, the move to Brazil was marked by emotional hardship: the suffocating heat, the weight of fear for family members left behind in war-torn Europe, and the silent, ever-present anguish over what was happening far away. Yet Rio also gave her something else, a different kind of distance. One that allowed her to explore new spaces, both psychological and pictorial. She and Szenes moved in intellectual circles, forging deep personal bonds with poets like Cecília Meireles and Murilo Mendes. “Great friendships were formed,” she later remembered, “but when it came to our work, we realised we couldn’t collaborate. So we each kept painting.” Their artistic paths diverged: Árpád began teaching, while Vieira da Silva immersed herself entirely in her painting practice. And what a creative flowering it was.

The works produced during this Brazilian exile are among the most profound in Vieira da Silva’s career. In them, humanity appears suffocated by grid-like architectures, as in The Encircled Men (1938), a harrowing forewarning of entrapment and surveillance. Later works, like The Garden of Rio (1944), burst forth with life, colour, and the chaotic exuberance of survival. The contrast is striking: in one, anguish and enclosure; in the other, vitality and resistance.

In these paintings, Vieira da Silva doesn’t illustrate events but absorbs them. Her lines become wounds, her brushstrokes, breaths. The war is never directly depicted, and yet it looms in every structure, every face, every spatial fold. In a place far from the frontlines, she paints an emotional geography of exile: where light is tropical but the shadows are European, where joy and horror lie side by side.

Above all, these canvases carry the pulse of someone struggling not just with displacement, but with the question of how to go on. Her work in Rio is a testament to the quiet, persistent labour of survival: not just bodily, but spiritual, visual, and artistic. A heartbeat faint but unbroken.

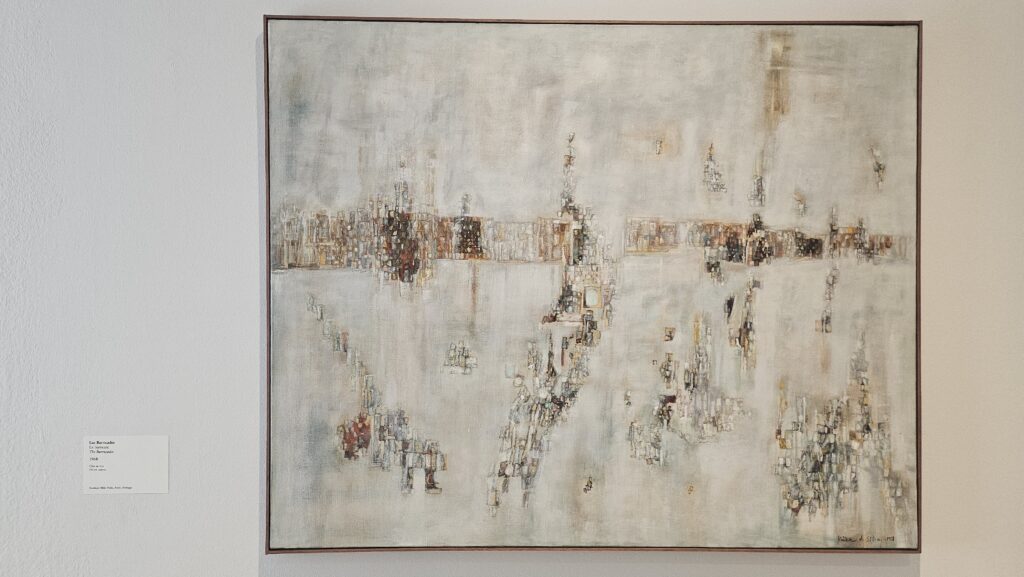

4. Cities, Real and Imagined

“I am a woman of the city,” Vieira da Silva once declared, and it’s a statement that resounds through every period of her life and practice. Cities were not just her places of residence: they were her intellectual ecosystems, her muses, her cartographies of thought. From Lisbon to Paris, from Rio de Janeiro back to postwar Europe, cities shaped not only how she lived, but how she painted, how she saw.

When Vieira da Silva returned to Paris after the war, she returned with new eyes. Her cityscapes became more than portraits of specific places: they transformed into meditations on what a city is, and what it means to inhabit one. Some works, like Festa veneziana (1949), evoke recognisable locations like Venice, rendered as a triumphant cascade of blues, evanescent and fluid like water itself. Others, like Paris (1951), with its frenzied latticework of intersecting lines, seem to pulse with metropolitan energy, bordering on abstraction.

But even when the city has a name, it may not be a map you can follow. Paris, la nuit (1951) offers a nocturnal mirage of the “City of Light,” more dream than document. In The City at Night and the Lights of the City (1950), the glow becomes almost spiritual, a ghost of lived experience. Conversely, in The Tentacular City (1954) and Figures in the Street (1948), Vieira da Silva captures something closer to urban alienation: the repetition, the static, the inescapable rhythm of anonymous crowds. These are cities stripped of landmarks. Cities where meaning is buried in routine.

One of the most striking pieces of this section is The City of the Staircases (1954), painted during a time of reconstruction and reinvention in Europe. It evokes a city that doesn’t quite exist: a metropolis without cars, floating upward in blue shafts of imagined light. “I think of an immense metropolis without automobiles,” she wrote, “where people move using only stairs and elevators. Not a gigantic skyscraper, but an architecture that rises softly, gently, into the blue.”

Here, we see how cities, for Vieira da Silva, become spaces of paradox: at once physical and imaginary, oppressive and liberating, ordered and chaotic. They are not backdrops, but characters—perhaps even autobiographical. In painting the city, she paints her place in it. In abstracting the city, she constructs a psychic architecture where personal history and collective space merge.

This section of the exhibition doesn’t just show us where Vieira da Silva lived—it lets us step into the cities she invented. And in doing so, it offers us the chance to get lost — joyfully, curiously — in her most enduring subject: the geometry of belonging.

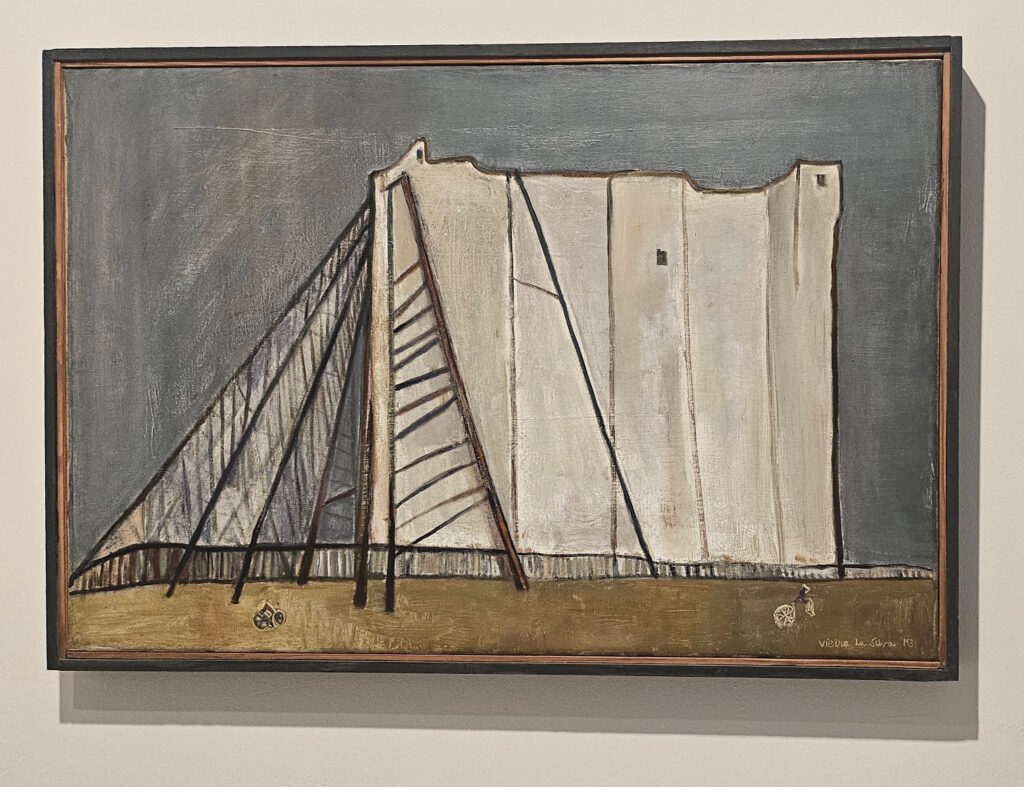

5. Grand Constructions

Maria Helena Vieira da Silva’s love for cities naturally extended to the buildings that compose them. In this section, we move from the cityscape to its structural skeletons: four paintings that focus on the idea of construction, not as finished architecture, but as process, scaffolding, and transformation. Two of the works, both titled Construction Site (1950), depict building sites not through architectural precision, but through evocative overlays of poles, grids, and tangled frameworks. There’s something almost musical about them: structures seen mid-growth, like fugues in concrete and steel.

In Gare Saint-Lazare (1949), an actual, completed Parisian train station becomes almost unrecognisable: dismantled and reassembled into a woven labyrinth. The composition denies clarity, insisting instead on complexity. Likewise, in The Gothic Chapel (1951), linear rigour gives way to baroque convolution. Lines curve and fold like ribs in a vaulted ceiling, evoking Gothic architecture not in form, but in spirit: elaborate, reverent, and a little haunted.

Critics have long noted Vieira da Silva’s affinity for architecture, and her husband Árpád Szenes confirmed it. But her vision went beyond buildings: she painted urbanism, space as social matrix, as experience. From the late 1940s through much of the 1950s, Vieira da Silva turned her brush to interiors and exteriors alike. What emerged wasn’t so much a depiction of architecture, but a reinvention of it.

These paintings explore spatial immensity through colour as much as line. Blues stretch, reds collapse, yellows pulse like beacons in a sea of grey. Sometimes her compositions feel dense and claustrophobic, other times airy and skeletal. In every case, they propose a new kind of architecture, born out of memory, intuition, and abstraction.

By the mid-1950s, Vieira da Silva’s architecture of the mind had become internationally recognised. Her spatial paintings were exhibited across the globe, from Lisbon to New York, Paris to Stockholm, and twice at the Venice Biennale (1950 and 1954), where she stood as a rare woman in a field still dominated by men. These great constructions are not just about what buildings are, but they ask what they could be. They frame architecture as an idea in flux, a choreography of lines, a place to think, to feel, and ultimately, to lose oneself in.

6. Labyrinth

The following room brings together some of the most representative works from Vieira da Silva’s career during the 1960s and 1970s. The tones are more subdued, the formats often larger, yet despite the change in scale and palette, one essential constant remains: the labyrinth.

From her earliest works to these more monumental canvases, Vieira da Silva was enthralled by rhythmic grids, tangled paths, and the ever-shifting interplay between line and space. The labyrinth, in her hands, was a philosophy, a way of seeing, a way of being.

Paintings such as The Barrier (1968) and The Man’s Path (1969) present checkerboard constructions that no longer trap the eye but instead offer openings, zones of visual relief and imaginary depth. These spaces are mental terrains where inside and outside blur, where time folds in on itself, where distance becomes immeasurable.

The 1975 work Daedalus makes the metaphor explicit. Named for the mythical architect of the labyrinth, it anchors this room conceptually. “I think I’ve lived my whole life inside labyrinths,” Vieira da Silva once confessed. “It’s how I look at the world.” From childhood, she felt drawn to complex spaces: intricate, impenetrable environments where progress was both possible and uncertain. Once you enter, she believed, the labyrinth becomes part of you. And yet, there is no fear in this wandering. By the time we reach these mature works, the labyrinth no longer imprisons. It invites. It becomes a metaphor not for entrapment, but for life itself: its twists and returns, its unknowable rhythms, the layers of memory and time it demands us to trace again and again. This final transformation is perhaps her most poignant: the labyrinth as a tool of remembrance. For Vieira da Silva, time was not linear, and memory was never simply a recollection of the past. It was spatial, vivid, alive. “Memory,” she wrote, “is like a wall that doesn’t divide the past from the present—but lets the past remain present.”

In these works, then, the artist becomes not just a painter of space, but a cartographer of memory. Each canvas is a path traced backwards and forward at once, asking not “Where are we?” but “Where have we been, and how do we carry it with us?”

7. Shades of White

This final room is a quiet, luminous tribute to the full arc of Vieira da Silva’s artistic journey: a retrospective within the retrospective. It gathers works from different periods of her career, all unified by a single element: the colour white.

At first, it might seem unexpected. Vieira da Silva is known for her masterful use of colour: deep reds, radiant blues, vibrant yellows, and brooding blacks dominate much of her work. The paintings displayed throughout the exhibition show how she orchestrated colour like a composer, layering harmonies. And yet, white—neutral, elusive—holds just as much power in her visual language.

In her later years, she increasingly turned to white, using it not as absence, but as fullness. Not as blankness, but as presence. These white-inflected works seek a kind of silence — a meditative stillness — where the noise of colour falls away and what remains is light. Space. Breath. Her partner, Árpád Szenes, once summarised this approach with piercing clarity:

“The problem of color is fascinating… In 1932 we started an experiment: to find every possible tone of white… all the shades needed so that the white would never remain an empty space, but a pictorial and plastic entity in itself. The intensity of color is only there to express the vibration of light. The importance of light is immense.”

White, for Vieira da Silva, was never sterile. It shimmered with nuance, it held memories, it carried a kind of transcendent vibration. This final room, then, becomes a chapel of sorts, dedicated to distillation and essence. It reminds us that in her search for space, Vieira da Silva was always reaching not just for new structures, but for clarity—for a place where light and thought converge. It is a luminous farewell. And like the best endings, it feels more like a beginning.

Recommended to…

…anyone who has ever been fascinated by the silent architecture of thought, and those who find poetry in grids and mystery in repetition. It will resonate deeply with lovers of modern art, of course, but also with architects, urban wanderers, and those drawn to the invisible structures that shape our lives. Whether you’re discovering Vieira da Silva for the first time or returning to her intricate worlds with familiarity, Anatomy of Space offers a quiet revelation into the production of this artist, and invites the patient viewer to lose themselves — and perhaps to find something — within her luminous, labyrinthine vision.

No Comments