Apparently Robert Louis Stevenson was written into my stars, this January: after reading Larsson’s take on Long John Silver, I wanted to read something Japanese and I picked a random volume from a series I bought a while ago, not even remembering what it was, and here we are.

What the hell did I just read?

Light, Wind and Dreams is a short, elusive work by Atsushi Nakajima, an early 20th-century Japanese novelist, and it resists easy classification. It didn’t help that the Italian publisher of my edition clearly loathes prefactions (I wrote about it already), so after a few pages I had to put it down and browse for information.

First published in 1942, it takes as its subject the final years of Robert Louis Stevenson, focusing in particular on the period Stevenson spent in Samoa and it’s based on reflections contained in his Vailima Letters. Yet Nakajima’s book is neither a biography nor a historical reconstruction in any conventional sense. Instead, it is a literary meditation that uses Stevenson’s life and writings as raw material for an exploration of illness, exile, creativity, and the fragile balance between body and spirit, all themes the author was personally familiar with.

At its core, Light, Wind and Dreams asks what it means to live and write under the constant shadow of physical limitation. In this context, Stevenson doesn’t feature as a monumental figure of Western literature, but as a vulnerable, reflective presence, observed at close range. Nakajima is less interested in factual accuracy than in emotional and existential truth, apparently, and I’m told episodes from Stevenson’s life are filtered through a restrained, almost translucent prose that matches Stevenson’s own literary agenda, where atmosphere matters more than chronology and inner states matter more than events. This approach places the book in a liminal space between biography and fiction. Nakajima draws directly from historical documents, yet he reshapes them freely, transforming anecdotes into scenes, impressions, and philosophical reflections. The result is not an adaptation of Stevenson’s words, but a parallel text that exists alongside them, and Stevenson is treated as a lens. Through this lens, the book reflects on broader themes: the experience of illness as both constraint and clarity, the desire to escape one’s cultural and physical boundaries, and the strange calm that can arise when life is lived with an awareness of its own precariousness, a concept that had to resonate with Nakajima’s cultural background.

More on the author

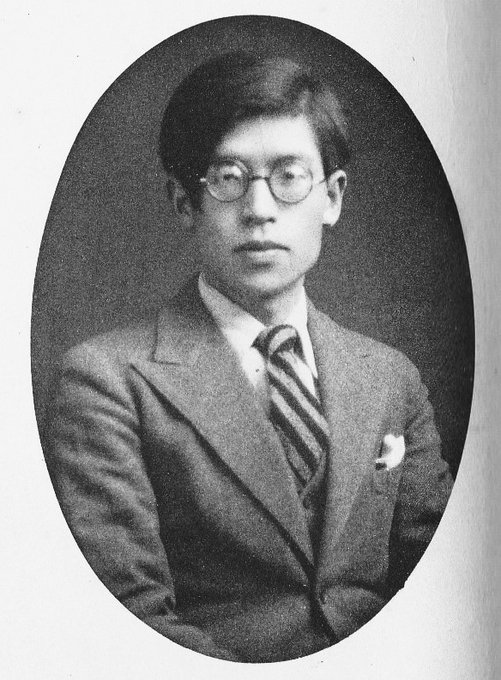

Atsushi Nakajima was born in Tokyo in 1909 into a family deeply connected to classical Chinese scholarship. This intellectual environment shaped his early education and left a lasting imprint on his literary sensibility, particularly in his attention to moral ambiguity, historical distance, and the tension between individual experience and inherited cultural forms. Nakajima came of age during a period of profound instability in Japan: the years leading up to and encompassing the Second World War, marked by imperial expansion, ideological rigidity, and increasing pressure on intellectual and artistic expression.

His literary career was brief but remarkably concentrated. Nakajima began publishing fiction in the late 1930s and early 1940s, producing most of his significant work in just a few years before his death in 1942, at the age of thirty-three. During this time, Japanese literature was often mobilised in the service of national narratives, yet Nakajima’s writing largely sidestepped overt political engagement. Instead, he turned toward distant settings, historical figures, and foreign cultures, choices that allowed him to reflect obliquely on contemporary anxieties without directly confronting the ideological constraints of his time.

By focusing on a Western writer living at the margins of empire rather than at its centre, Nakajima avoided both patriotic exaltation and explicit dissent. The book’s inward gaze and restrained tone stand in contrast to the dominant literary currents of wartime Japan, emphasising introspection over affirmation and fragility over heroism.

Influences

Nakajima’s literary influences are notably eclectic: his deep familiarity with classical Chinese literature provided him with a model of concise expression and reflection, while his engagement with Western authors introduced him to psychological interiority and modern narrative experimentation. Writers such as Robert Louis Stevenson, Franz Kafka, and Anatole France have often been cited as points of reference, though Nakajima’s work can’t be reduced to direct imitation, as Light, Wind and Dreams clearly shows. Rather than adopting specific stylistic techniques, he absorbed their shared concern with uncertainty, self-division, and the limits of rational control in ways that are fascinatingly multicultural. This is why Light, Wind and Dreams is particularly important: these themes find a particularly subtle expression in this book, and Stevenson becomes a figure through whom Nakajima can explore the act of writing itself, not as triumph or mastery, but as a fragile negotiation between desire and the limitations imposed by… well, everything. Literature appears as an ontological necessity, for Stevenson, a means of self-assertion and a way of enduring that has very little to do with fame and a far more domestic tone to it. So, let’s see some of these themes.

Illness, Exile, and the Sense of Impermanence

Illness plays a central role in Nakajima’s life and writing: he suffered from chronic asthma from a young age, a condition that repeatedly disrupted his daily life and ultimately contributed to his early death. This persistent awareness of physical vulnerability shaped his worldview, fostering an acute sensitivity to the body’s limits and to the tenuous nature of human plans.

Exile, both literal and metaphorical, also marked Nakajima’s experience. In 1941, he travelled to Micronesia (then a territory under Japanese mandate), an experience that deepened his sense of dislocation and estrangement. Although this journey occurred late in his life, the feeling of being out of place — geographically, culturally, or physically — had long been present in his writing. His characters often inhabit spaces that feel as though they might dissolve at any moment.

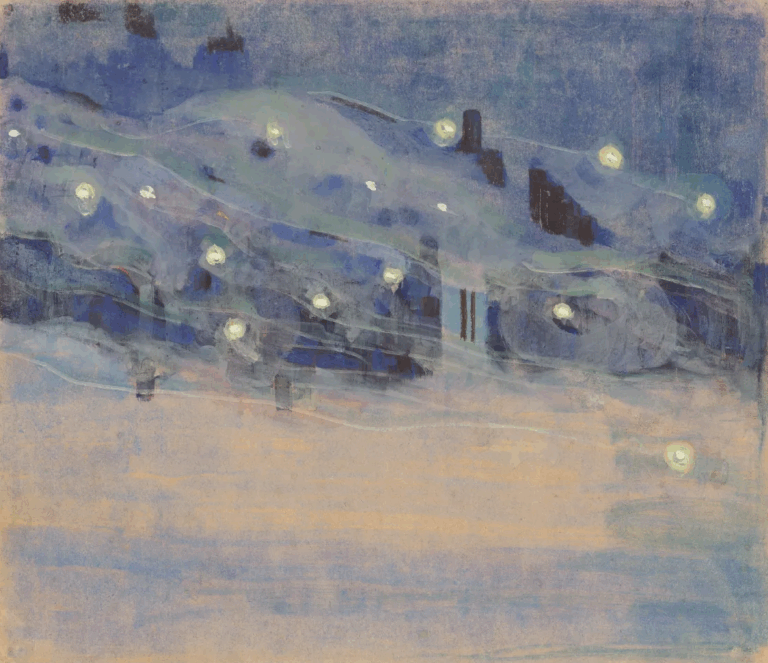

This convergence of illness and exile feeds into a broader sense of impermanence that permeates Nakajima’s work. Life is portrayed as something light and unstable, shaped by forces beyond individual control. In Light, Wind and Dreams, this sensibility finds a natural counterpart in Stevenson’s own fragile health and self-imposed distance from his homeland. The emphasis on nature, elements and fleeting impressions reflects an acceptance of transience as an essential condition of existence.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s Vailima Letters

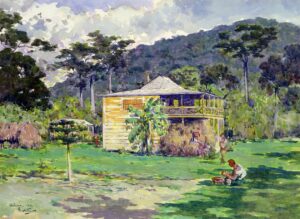

As we were saying, Robert Louis Stevenson settled in Samoa in the final years of his life, seeking relief from the chronic respiratory illness that had shaped much of his adult existence. After years of travel driven as much by medical necessity as by restlessness, he purchased an estate near Apia, naming it Vailima (five streams). There, far from Britain and the literary circles that had first brought him fame, Stevenson attempted to construct a life balanced between physical survival and creative fulfilment.

Samoa was not simply a backdrop for convalescence, as it happened for other Westerners: Stevenson became deeply involved in local affairs, forming close relationships with Samoan leaders and observing, often critically, the colonial tensions between European powers. Yet his engagement with the islands was marked by ambivalence. While the climate offered temporary relief, his health remained precarious, and his position as a European intellectual in the Pacific was inevitably fraught. This mixture of immersion and estrangement is central to the tone of the Vailima Letters and to their later resonance for Nakajima.

The Vailima Letters are a collection of personal correspondence written by Stevenson during his time in Samoa and addressed primarily to friends, family, and literary peers. Unlike formal essays or fictional works, these letters occupy an intimate space and record daily routines, shifts in health, observations of landscape and weather, reflections on work in progress. Their style is often informal, playful, yet beneath this surface lies a persistent awareness of Stevenson’s impending mortality, which is very Japanese.

What distinguishes the Vailima Letters is their oscillation between lightness and gravity: Stevenson frequently adopts a tone of ironic detachment, even when describing physical suffering or political frustration. The letters do not present a coherent narrative of decline or triumph; instead, they accumulate as fragments of lived experience, and this fragmentary quality allows moments of serenity and humour to coexist with fatigue and anxiety, creating a portrait of a writer living in suspension between hope and resignation.

For Nakajima, this form was crucial. The letters offered access to a literary voice caught in the flow of everyday life, a voice that reveals itself through interruptions, digressions, and fleeting impressions rather than through polished argument. In Light, Wind and Dreams, Nakajima transforms the Vailima Letters from historical documents into a generative literary space: rather than quoting or closely paraphrasing Stevenson’s correspondence, he distils their atmosphere and emotional cadence and uses them as a tonal and thematic foundation for original narrative.

This transformation involves a deliberate shift in perspective. The immediacy of the epistolary form — addressed to specific individuals and anchored in particular moments — is replaced by the contemplative distance of a diary. Nakajima selects, condenses, and reimagines Stevenson’s reflections and transforms them into a broader meditation on illness, isolation, and creative endurance.

The result is weird and yet fascinating.

No Comments