Before I start laying out what I thought of this book, let me be upfront about a couple of things.

- I don’t like Kubrick. I like some of his movies (mostly Full Metal Jacket and some parts of A Space Odyssey), and I recognise the historical importance of some others (Dr. Strangelove, A Clockwork Orange and The Shining), but I always grow suspicious of these overinflated geniuses of cinema, Tarantino being another one of them. I’ll elaborate on that later on.

- A Space Odyssey isn’t a movie I particularly like. While I enjoy the construction of the computer’s character, and all the work that went into it as I wrote this week), and I love the premise, I think the execution was too full of itself, and the end result is a confusing pastiche of things not said, long silences, and other authorial bullshit. They worked on it for too much time, and lost sight of the story they were trying to tell.

- I bought this book for the pictures. There, I said it. I own many Taschen books, and I can’t say I read all of them. I’m not even sure I read half of them.

With these premises, you can imagine my surprise when I found myself avidly reading the many sections drafted by Piers Bizony and sometimes skipping the pictures to reach the next section. So let us start from there.

The Prose

Piers Bizony is a journalist specialised in technology, with a particular knack for outer space and special effects, which makes him one of the best guys to tackle the endeavour of telling the story of how A Space Odyssey came to be, and telling it through a holistic approach that doesn’t focus just on one aspect. Other than this, he wrote an acclaimed biography of the Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, a splendid The Art of NASA: the Illustrations that Sold the Missions, and the very interesting The Man Who Ran the Moon: James E. Webb, NASA, and the Secret History of Project Apollo.

The book is divided into:

- Journey Beyond the Stars, with some of the backstories from Spartacus to Dr. Strangelove, and introducing the meeting between Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke;

- A Kind of Infinite Space, concerning some of the most important changes: how HAL was changed from the benevolent Athena, how we went to Jupiter eventually, and the evolution of the spaceship;

- Santa’s Workshop, on some of the practical effects that were employed, from the matte shot to some of the camera tricks;

- The Dawn of Man, on the making of the very first shot and how a group of mimes was recruited and turned into apes;

- Stanley on Set, which I skipped for reasons I’ll explain later;

- They Hated it, They Loved it, on the first disastrous screening, the critics’ first response and then how the tide turned when the movie became a counter-culture idol;

- Yesterday’s Tomorrow, on how the future envisaged in the movie aligns (or doesn’t) with what actually happened in terms of space exploration, and the privatisation of space flights.

- Are we alone? on one of the main topics that didn’t explicitly make into the movie: the presence of aliens.

- Film Synopsis, with the detailed description of what happens, in case you need help on whatever the fuck’s going on with the ending.

Every section is abundant with references, quotes, and the prose runs as smoothly as water, which is the good news. You can follow the production through its many stages from the different points of view: the backlog of Kubrick and how he didn’t want to work with famous actors after Spartacus (which is understandable); the meeting with Arthur C. Clarke and how they clicked, being both out of their freaking minds; the research into the plausibility of a supercomputer, of apes during the dawn of men, of aliens (or not) and so on. It’s very, very good, its enthusiasm is contagious, and it makes you want to jump onto a milk train early in the morning to go and photograph possible alternatives to the Sahara desert in Great Britain, to buy complex machinery and build weird contraptions, to write until your fingers fall out.

It wasn’t until the description of the rotating space station that things started to feel weird. There were signs before, sure, when the author mentions how Kubrick liked to work at weird hours (which is fine) and had a habit of waking up his collaborators at those hours (which is NOT fine). The final blow, however, was delivered in section n.7, Yesterday’s Tomorrow, while addressing an issue that hadn’t occurred to me: that Kubrick spent much time in trying to figure out the most accurate depiction of future technology and space travel, while merrily walking into a movie where there’s no nonwhite man (A Space Odyssey is from 1968 and, before someone says that Kubrick was “a man of his time”, Rosa Parks refused to move in 1955, while the first black astronaut was selected in 1967), and women are hostesses (Roddenberry envisioned a female number one for the pilot of Star Trek, “The Cage”, back in 1964).

Kubrick was certainly interested in addressing the main problems of “white-dominated society”, as this essay tries to point out, but certainly not in a way that involved non-white voices or figures in this critique. The same can be said for the figure of women, and it’s clear in that supreme crap that’s Eyes Wide Shut: the man’s perspective, very aptly conveyed through the specific choice of an asshole as an actor, is the only one emerging in the story, even if it’s a story about the maladies of fantasies, and the final chapter of Schnitzler’s novel, conveying the wife’s wide-eyed dream, is reduced to the wife telling the husband that they should fuck.

Back to the point, Kubrick was certainly interested in crafting a critique of certain worlds and, in doing that, he often became a part of that same world: a violent, white man’s world. This is a discourse worthy of exploring. Bizony, on the other hand, mentions that A Space Odyssey has a “lack of nonwhite characters or significant women in commanding roles,” while discussing Kubrick’s success in depicting a plausible future, but then defines “quibbles” any criticism aimed at addressing these issues. Quibbles my ass. But then again, this below is how Bizony looks like.

That passage in “Yesterday’s Tomorrow” was a shock, and it made me realise why I had skipped the chapter “Stanley on Set.” It wasn’t because I was not interested in reading that aspect, and it wasn’t just my disliking of Kubrick, but my personal diffidence towards him piled up with a certain amount of agiographic tone that had already been willing to downplay Kubrick’s responsibility when his whims caused injuries and illnesses on set. I don’t think these are aspects we can overlook, while talking about a director, even if we’re willing to admit he was “a genius.” You’re a genius when you can achieve your vision while taking care of the people who work for you. If not, you’re just another asshole.

The Pictures

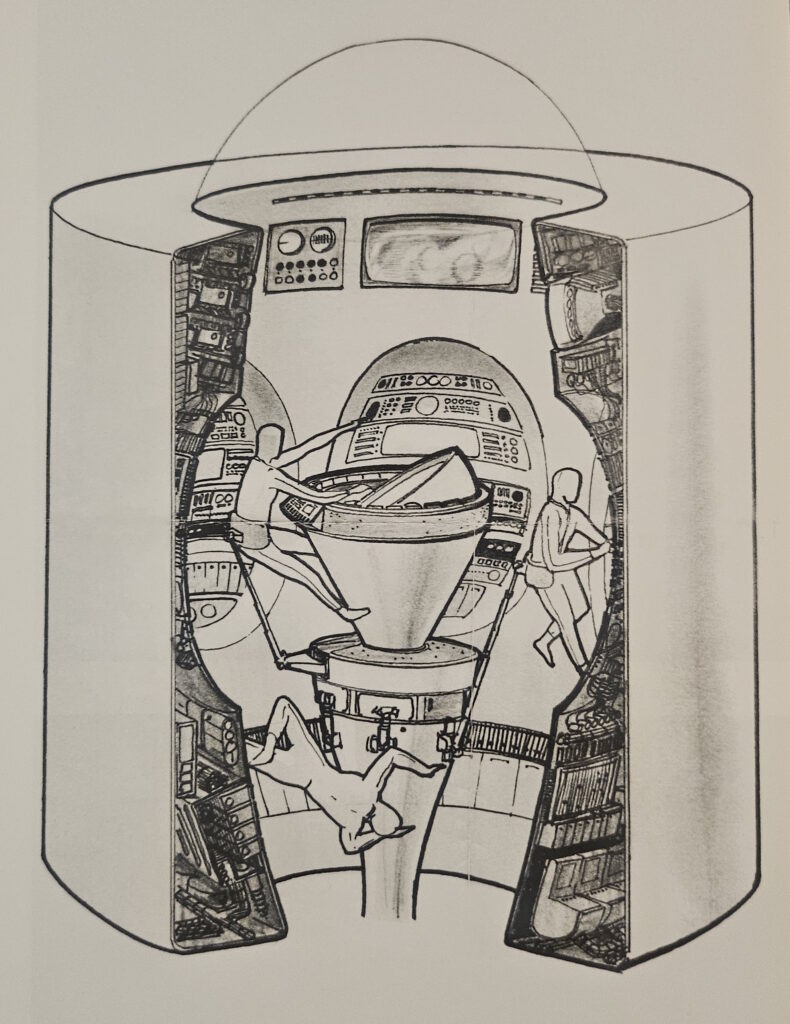

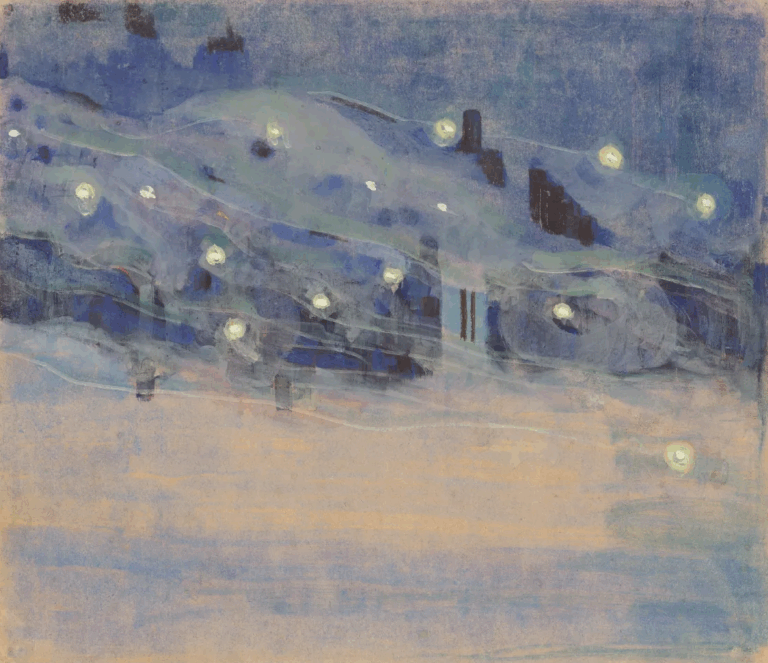

That being said, the collection of pictures is astonishing and almost all illustrators are properly credited, which wasn’t obvious. The fact that many pictures are miniaturised next to the text also helps to put them in context of the different sections, and so you have properly contextualised selection of illustrations, pictures, graphics, photos and technical drawings that of course were my favourite.

The Format

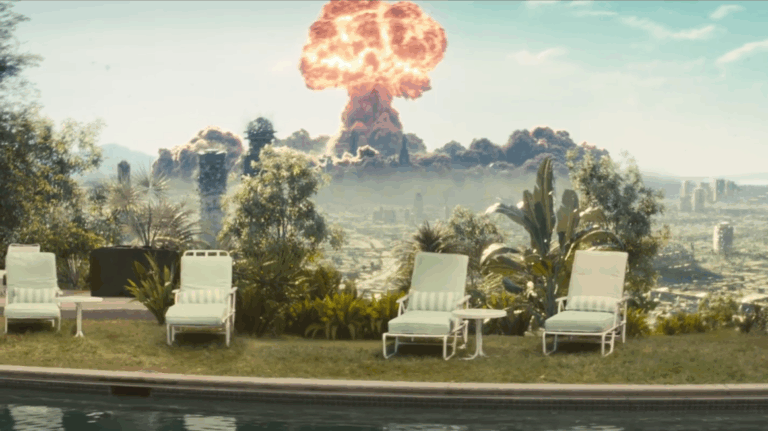

Now for the bad part. The book is tall and narrow, like the monolith, which I’m sure someone thought was an idea worthy of Kubrick and in one way it is: it’s captivating and equally unpractical, up to the point of being uncomfortable and damaging the actual content. Yes, because most of the pictures are horizontal – like the Cinerama screen, like life – and this means they’re consistently cut in half. And, to quote Resient Alien’s Harry…

Still, regardless of everything, it’s a book I recommend. It’s well written, well researched, and a rich repository of material for a movie which importance needs to be recognised.

No Comments