I’ve known the work of Yoshitaka Amano for years even without knowing it was his, and so have you. He’s the mastermind behind Final Fantasy but you might also know him for his work in The Sandman, and there’s a splendid exhibition in Milan showcasing his work. I went to see it last week. Here are some impressions.

Amano Corpus Anime

Let’s start with a little context as provided by the introduction to this exhibition, according to which Yoshitaka Amano has carved out a space comparable to Gustav Klimt and Andy Warhol. Klimt merged fine art with the decorative, and Warhol gleefully erased the line between high art and pop culture. Amano? Well, he merges fine art with pop storytelling, and his traditional techniques embrace experimental media. Even if you might think this to be quite a stretch, it’s undeniable that the Shizuoka-born maestro has become one of the most iconic visual storytellers of our time.

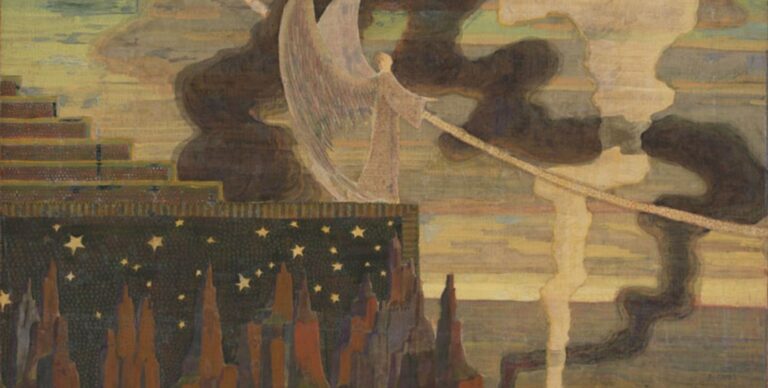

So, what really sets Amano apart from other artists? His uncanny ability to walk that tightrope between opposites: Japanese traditions on one side, and the surreal, boundary-pushing experimentation of movements like Art Nouveau and Surrealism on the other.

“I’ve seen too many artists fall into the trap of sticking to a rigid style,” Amano once mused, and he’s going out of his way to dodge that bullet. His relentless pursuit of innovation has kept his art ever-evolving, defying categorization. If Amano’s career were a playlist, it would be full of unexpected genre shifts—one minute, you’re vibing to serene harmonies, and the next, you’re headbanging to experimental beats.

This brings us to Amano Corpus Anime, the exhibition in Milan, which is a grand retrospective that feels less like an exhibition and more like stepping into fifty years of dreams. Over 130 works from his archives in Tokyo have been gathered to showcase Amano’s incredible journey. From the delicate and ethereal illustrations for Vampire Hunter D and The Sandman to unforgettable designs for animations like Kyashan, Yattaman, Tekkaman, and the saddest Pinocchio ever created, the exhibition is a time machine of visual wonders. And, of course, who could forget his fingerprints on the global phenomenon that is Final Fantasy?

The retrospective itself is organized like a journey. It begins with his earliest work in the Tatsunoko Production studio back in 1982 (I wasn’t even born back then) and moves through the decades, spotlighting his evolution from animator to full-fledged fine artist. Three thematic zones anchor the exhibit: Game Master, Free Spirit, and Global Resonance. Each represents a slice of his creative DNA, from the mythic and narrative-driven to the deeply personal and universally expressive.

And here’s the cherry on top: the showcase concludes with his latest creations, including a Puccini trilogy specially crafted for Lucca Comics & Games 2024. Just when you think Amano has done it all. So whether you’re a die-hard Final Fantasy fan, a lover of surrealism, or someone who just appreciates art that’s both timeless and trailblazing, Amano’s work offers something magical, and you can’t miss this exhibition.

Now for the bad news.

The space is not that large and, though it showcases a lot of works, you step from rooms where each work is correctly spotlighted to sequences like the Final Fantasy corridor where there’s no real explanation of whatever the heck is going on and the sequence of works is crammed together in a way that doesn’t really give them justice. Still, it’s highly worth a visit.

As usual, let’s see it room by room.

1. The Early Decades

Born on March 26, 1952 in the Shizuoka Prefecture, Yoshitaka Amano was the youngest of four siblings. His father, Yoshio Amano, was a renowned craftsman specializing in lacquerware—a heritage that perhaps planted the seeds of artistry in young Yoshitaka though he lost him when he was ten. And while the world of lacquerwork wasn’t his calling, he found his first muse closer to home in his brother Keisano Fujimoto and his sister Yaeko. His boundless energy and obsession with drawing manifested very early, alongside an insatiable hunger for creation, and he sketched prolifically on any surface available.

Fast forward to December 1966: a young Amano took a life-changing trip to Tokyo to meet a family friend. Little did he know that this visit would land him at Tatsunoko Production Studio, where his sketch portfolio caught the attention of none other than animation legend Tatsuo Yoshida. At just 15 years old, Amano joined the studio, leaving behind his hometown to dive headfirst into the bustling world of animation. It wasn’t long before his talent began to shine.

His first big project was working as a character designer on Mach Go Go Go! (aka Speed Racer), a show that would later become a global pop culture phenomenon. By 1969, Amano had his hands on classics like Science Ninja Team Gatchaman (Battle of the Planets) and Casshan (Casshern), earning him a reputation as the designer of powerful characters. But it wasn’t just his skill with characters that set him apart—it was his ability to bring an otherworldly flair to his creations. While the bustling “character rooms” of Tatsunoko churned out content, Amano developed a unique signature style that would soon take him beyond the studio walls. He wasn’t just designing; he was crafting stories.

By his twenties, Amano was already a legend. He contributed to countless beloved series, including Time Bokan, Ippatsu Kanta-kun, Tekkaman, Hurricane Polymar, and many more. It’s no surprise that his peers and mentors, such as Mamoru Oshii and Masami Suda, recognized his brilliance. And while Tatsunoko Studio buzzed with talent, Amano stood out for his bold and experimental approach, consistently delivering designs that redefined animation aesthetics.

1.1. The Saddest Pinocchio Ever Created

I have very fond memories of a discussion with a Japanese colleague from Tokyo, a few decades ago, in which he was complaining that we Europeans think Japanese cartoons are sad and full of suffering, while they really aren’t. One was the title that was able to convince him of our point—the 1976 Pinocchio.

Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio, published way back in 1883, is one of the most famous in the world and one of my least favourite, with its moralistic messages and its Masonic undertones, and especially its bourgeois views on the virtues of the poor (spoiler: it is not creating trouble). That being said, the story contains iconographic gems intimately connected to the original illustrations. And this is where things get interesting in connection to Amano.

Collodi’s Pinocchio has been reimagined and brought to life by countless artists over the years, but its earliest iterations were enriched by the iconic work of Enrico Mazzanti. His woodcuts helped carve the mischievous marionette into the public’s imagination, giving Pinocchio his first face and personality.

Fast-forward a few decades, and another master of Italian woodcutting enters the scene: Antonio Rubino. In 1911, Rubino breathed new life into Pinocchio, presenting the tale with an almost avant-garde aesthetic that hinted at the early stirrings of modernism.

Yoshitaka Amano’s take on Pinocchio seems more connected to these two references than to other, more recent interpretations and offers a striking blend of East-meets-West, tradition-meets-experimentation. Amano, with his ethereal and surreal style, provides a Pinocchio that feels as timeless as it is fresh. It’s also the stuff of nightmares, as the illustration below will exemplify.

However, Amano wasn’t content with simply haunting our nightmares and being part of the Japanese animation crowd—he was ready to take his artistic vision to new heights. After the untimely passing of his mentor Tatsuo Yoshida in 1977, Amano began exploring new horizons. His focus shifted toward freelance artistry, and by 1982, he left Tatsunoko to fully embrace the life of an independent artist.

2. The Early Freelance Year

Yoshitaka Amano’s creative journey hit a major turning point in March 1981, when his monthly comic strip Twilight Worlds debuted in S-F Magazine. Breaking free from the aesthetics of Tatsunoko Studio, Amano began cultivating a distinctly personal, international artistic style that would soon become his hallmark.

Between 1982 and 1986, Amano embarked on an intense whirlwind of creativity as an illustrator. He lent his artistic genius to a slew of international publications, with the Japanese fantasy market taking particular notice. Among these collaborations, one of the most iconic was with Michael Moorcock, the legendary author of the Elric of Melniboné series.

In January 1983, Amano’s art graced the pages of Vampire Hunter D by Hideyuki Kikuchi, a groundbreaking series that would cement his reputation as a master illustrator. With over 120 volumes of Kikuchi’s novels featuring Amano’s work, this collaboration wasn’t just a partnership—it was a creative dynasty. The gothic, atmospheric visuals Amano brought to Vampire Hunter D perfectly matched its eerie and epic tone, making it a cultural touchstone. During this period, Amano’s personal life saw the birth of his three children: Kikuchi (1983), Take (1986), and Hina (1990). Their faces sometimes provided inspiration for his art.

One of the defining moments of this era was Amano’s foray into movies. In 1985, he collaborated with Mamoru Oshii to work on Angel’s Egg. This animated movie was a stark departure from conventional storytelling. Instead of focusing on dialogue and action, it leaned heavily on surreal imagery, gothic architecture, and cryptic symbolism.

Despite its almost hermetic, mysterious nature—or perhaps because of it—Angel’s Egg became a cult masterpiece. Critics couldn’t agree on what it all meant, but that only added to its allure. Amano’s haunting, dreamlike designs elevated the film into an avant-garde treasure, marking a pivotal point in his artistic career.

By the late 1980s, Amano had established himself as an artistic juggernaut, redefining fantasy art and animation with his unique vision.

2.1. An Incursion into Fashion

Amano has always had a soft spot for haute couture, particularly the elegance of Italian fashion houses. By the late 1990s, this love had turned professional as he dived into costume design for global campaigns, stage productions, and his own creations. It was a natural extension of his art. After countless imagined outfits and accessories for his characters, we land in January 2020 when Vogue Italia decided to take a bold step to celebrate beauty beyond photography and asked a handpicked group of illustrators to reinterpret high fashion in their unique styles. Amano was on this exclusive roster, tasked with reimagining modern garments with his signature ethereal touch.

For this special issue, themed around the Renaissance, Amano faced a delightful challenge: to illustrate actual garments from the collections of Gucci and Giorgio Armani, all worn by model Lindsey Wixson. The result was nine illustrations featuring Amano’s delicate, flowing lines and attention to detail that elevate the garments into something almost divine. His work captures not just the clothing but the essence of the wearer, making each piece feel like a window into a dreamscape.

3. Final Fantasy

When Hironobu Sakaguchi, the mastermind behind Final Fantasy, first began crafting the iconic series for the Nintendo Famicom, he faced a monumental challenge: creating a visually unique universe that would stand out in a rapidly growing video game industry. Just a year earlier, in 1986, Dragon Quest by Enix had made waves, revolutionizing the RPG genre in Japan. For that title, Akira Toriyama (famed for Dragon Ball and Dr. Slump) played a key role in shaping the look and feel of the characters. His designs were so charming and instantly recognizable that they became inseparable from the game’s appeal.

Sakaguchi, understanding the importance of creating an equally strong visual identity for Final Fantasy, sought out an artistic direction that felt more mature and evocative. His main choices were Yoshitaka Amano and Moebius, and I will never stop wondering how Final Fantasy would have come out had he chosen the other option.

The choice historically felt to Yoshitaka Amano. Drawing inspiration from a blend of Western fantasy aesthetics and his own unique visual language, Amano transformed Final Fantasy from a game to an aesthetic experience. Alongside the unforgettable music of Nobuo Uematsu and the innovative programming of Nasir Gebelli, Amano’s art brought Sakaguchi’s vision to life.

Amano’s work on the original Final Fantasy games established many of the series’ enduring visual hallmarks with an intricate character design and ethereal landscapes, creating a distinctive identity that set it apart from competitors. His influence was so profound that, even as the series evolved with 3D models and cutting-edge technology, Amano’s illustrations continued to serve as the soul of Final Fantasy.

From 1987 to today, Amano’s contributions have spanned 16 mainline titles, countless spin-offs, animated adaptations, and a sea of merchandise. His delicate yet powerful designs are cultural artifacts that resonate deeply with fans around the globe, including this one.

4. Videogames beyond Final Fantasy

While the name Yoshitaka Amano is forever intertwined with Final Fantasy, his contributions to the gaming world stretch far beyond this iconic series. Over the years, Amano has collaborated with numerous Japanese production studios, leaving his mark on a diverse array of games that showcase his boundless creativity and versatility.

Amano’s first foray into the video game world was in 1984, when he worked as the character designer for the graphic adventure Angel’s Adventure: Eshtel Audronilla no Ehon. This early project, developed by Alfa Luna, was inspired by the success of Dragon Lair and set the stage for Amano’s growing influence in the industry. His role wasn’t limited to character design—he also crafted packaging and promotional materials, bringing his artistic touch to every aspect of the game’s identity. Later, he teamed up with Kure Software Koubo on First Queen, a game that debuted on the NEC PC-88 and Sharp X68000, platforms that were state-of-the-art at the time.

For Square Enix (then Squaresoft), Amano played a significant role in shaping several beloved titles beyond Final Fantasy. He designed the strikingly atmospheric characters and environments of Front Mission (1994) and Front Mission: Gun Hazard (1996), games set in dystopian futures brimming with intrigue and mecha drama.

One standout in Amano’s diverse gaming portfolio is his work on El Dorado Gate, a fascinating episodic RPG developed by Capcom for the Sega Dreamcast. Released exclusively in Japan between October 2000 and October 2001, El Dorado Gate married Amano’s unique visual storytelling with innovative gameplay mechanics, making it a cult classic for RPG enthusiasts. The game’s world-building and character designs, steeped in Amano’s dreamlike aesthetic, left an indelible impression.

In the 21st century, Amano continued to evolve as a creative force in gaming. He crafted the cover art for Rebus of Atlas and lent his visionary style to Lord of Arcana for Square Enix, a project that reunited him with Final Fantasy creator Hironobu Sakaguchi. He also designed exclusive posters for Child of Light by Ubisoft and contributed art to Cuphead by Studio MDHR, proving that his artistic reach knows no genre boundaries.

And let’s not forget his latest gaming collaboration! In 2023, Amano partnered with Epic Games to create the character Crossheart and a series of accessories for the celebrated Fortnite.

5. Sandman: The Dream Hunters

Editor Jenny Lee eventually fell in love with Amano’s artwork, sparking an idea that would bridge the world of British graphic novels and Japanese artistry. In 1998, Yoshitaka Amano was invited to create the celebratory cover for the 10th anniversary of Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman, and Gaiman was instantly captivated by the concept of bringing Amano’s ethereal style into the Sandman universe. In 1999, The Sandman: The Dream Hunters was born. Written by Gaiman and illustrated by Amano, this standalone masterpiece captured the imagination of fans worldwide, earning the prestigious Bram Stoker Award for illustrated narrative. It wasn’t just a graphic novel—it was a fusion of two artistic worlds, combining the mystical philosophy of Gaiman’s writing with the transcendent beauty of Amano’s art.

Amano’s illustrations carry a contemplative, almost meditative quality, perfectly complementing the philosophical depth of Gaiman’s storytelling. The imagery is steeped in Japanese mythology and tradition, drawing heavily from Heian-period aesthetics from the enchanting white fox spirit to Buddhist monks. His use of soft, fluid lines and rich, evocative colours imbues each image with a spiritual quality that transcends the page. This is definitely one of his favourite works of mine.

6. Marvel and DC Comics

By the dawn of the new millennium, Amano’s international acclaim was soaring due to his groundbreaking work on Final Fantasy and the global success of The Sandman: The Dream Hunters. DC Comics entrusted Amano with a series of alternate covers and posters for some of their most iconic characters, from Superman to Batman to Batgirl, Harley Quinn, and Suicide Squad. Amano reimagined them with his signature style—a blend of surreal elegance and mythic energy.

But DC wasn’t the only one eager to collaborate. Amano’s talent also caught the attention of Virgin Comics, where he partnered on projects with legendary director John Woo. Marvel Comics joined the mix too, roping him in for a trilogy of The Punisher written by Greg Rucka, featuring Elektra and Wolverine. It’s almost unfair—these characters were already cool, but Amano’s touch elevated them to a whole new level of almost operatic sophistication.

7. Three Odder Oddities

There would be so much more to show you, but I’ll close with one of the most charming spaces in the exhibition, which is dedicated to three special pieces:

an illustration of David Bowie…

…the Japanese movie poster for The Shape of Water…

… and the illustration for a Magic card.

No Comments