Piero della Francesca was born in Borgo San Sepolcro, Tuscany, in 1412. This will be important later.

After spending decades honing his craft, he was hailed as both a great mathematician and an unparalleled painter, celebrated for his mastery of light and space. If we understand anything about perspective, we owe it to him. If oil painting came out of the Flemish area, we owe it to him.

Despite his travels to various Italian courts and cities like Arezzo, he maintained a deep connection to his hometown, often returning to its familiar embrace and answering when it called.

And it did call, in 1454, when an altarpiece was commissioned for the high altar of the Church of Sant’Agostino in Borgo San Sepolcro, Italy, and its commissioner had to adapt purchasing a wooden structure created and then abandoned for another altarpiece, almost thirty years earlier, for another church and the rival Franciscan order of monks.

The wooden structure was fully Gothic. Piero is the forerunner of Renaissance. An uneasy mixture, in a town legendarily founded by pilgrims carrying relics of the Holy Sepulcher, whose legacy had already been celebrated by the rivalling Resurrection Polyptych (1350) painted by the Sienese Niccolò di Segna (below).

Piero asked for eight years. It will take him fifteen years and, after I’m done with you, you’ll have no trouble imagining why.

The Political Context

I said the Franciscan and the Augustinians were rivals and I don’t have enough space to expand on it here. It’s also not particularly relevant to the content of the Altarpiece. What’s more relevant is putting it in the context of the Council of Siena.

The Council of Siena, also known as the Conciliar Movement of Siena-Pavia, took place between 1423 and 1424, and it was an attempt to reform the Catholic Church during a period known as the Western Schism. We were in the midst of a great unrest: Jan Hus, who had been pushing for reformations and had been promised safe conduct, had been burned as a heretic in Prague in 1415; John Wycliffe was promoting reformations across the English Channel (and he will later be considered one of the forerunners of Protestantism); the Aragonese Pedro de Luna had nominated himself Pope Benedict XIII in Avignon and the Church had two popes.

Pope Martin V initially planned to follow-up on the famed Council of Constance (1414-1418), and the designated seat for this follow-up was going to be Pavia. Only one problem, though: in Pavia the plague was running rampant. And, being very religious men who strongly believed in the afterlife, Bishops and Cardinals were scared shitless of dying. The council was moved to Siena, and met from April 1423 to February 1424, and it laid the foundations for negotiations with the Eastern Orthodox churches. Its proceedings were kept a secret and only one artist was allowed to enter the room, just as you only allow one in the American courtrooms. Drawings start to circulate, depicting the attires of the Oriental Churches, and Piero decides his Altarpiece will send a political message of unity.

A Broken Masterwork

As paradoxical as it might sound, the complete Altarpiece didn’t survive, and that’s at the centre of the operation carried out by the museum in Milan.

From the main order, four pieces survive: a Saint Agustine, usually at the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga in Lisbon; a Saint Michael Archangel, usually at the National Gallery in London; a Saint John the Evangelist, usually at the Frick Collection in New York and the Frick collection is forbidden to lend its works unless it’s closed for renovation… which it currently is; a St Nicholas of Tolentino, regularly hosted at this very same museum in Milan.

From what’s now recognised as the lower order (don’t look at the Wikipedia page: that reconstruction is wrong), we only have three pieces: a Saint Monica, a Saint Agostinian, and a Crucifixion scene, all from the Frick collection. An additional piece is usually attributed to this Altarpiece, a Saint Apollonia at the National Gallery in Washington, but it’s either they couldn’t borrow it or they don’t agree with the attribution, because it isn’t in the exhibition nor do we see a space for it in the reconstruction.

Here’s a plausible reconstruction, so that we can all weep together at the thought of how many pieces are lost.

What’s political about it?

Well, dedicated to the one guy who ran away disgusted when I wrote that everything is political, here we are again. Piero is very meticulous when he picks the clothing for his main four saints. Let’s see them one by one.

Saint Augustine

The host of the Altarpiece, head of the order of monks who commissioned it, it’s placed at the far left of the composition, and we know it because Piero decides to dismantle the original Gothic structure by removing the frames and creating a single, continuous scene. I can almost imagine him, a forty-two years old dude with a screwdriver, fussing and cursing at this fucking Gothic relic they had him working on.

The first choice is of course to dress him as a bishop, with a tiara and a transparent staff. His ceremonial embroidered coat is called pianeta, and Piero decides to paint a cycle within the cycle, showing us scenes from the life of the Virgin and the childhood of Christ: the Annunciation, the Nativity, the Flight to Egypt, the Presentation at the Temple, the Crucifixion and some other scenes we can’t quite see. The overcoat is decorated with a continuous branch and foliage in fashion at the time and apparently they checked with simulation software, and the decoration is indeed continuous because Piero della Francesca kicked some serious asses.

Beneath the sumptuous coats, however, the Saint wears a cassock, which he never did. Piero is conjoining ceremony and poverty, the high ranks of the church with the vows of poverty from the monastical orders. Which was bold at the time. Very bold.

Saint Nicholas from Tolentino

At the far opposite side of the composition we find San Nicola da Tolentino, in full cassock attire. He was a very recent Augustinian saint (from 1446), and he’s painted sideways because Piero didn’t like frontal, boring scenes. There’s a star, next to his eye, and legend says that a star appeared in the sky when he was born.

He’s the contemporary church, and some scholar speculate that the face was painted from life, and that it’s the abbot who commissioned the painting.

Saint John the Evangelist

Flanking Saint Nicholas, drawing closer to the mysterious missing central scene, next up is a glorious Saint John, depicted as an elderly man and wrapped in a sumptuous red coat. He holds a heavy book (boy does that thing look heavy) and his coronet is not dissimilar to the one of the abbot next to him, but his clothing is traditional, reminiscing of how people imagined people to be dressed back in the years when Christ was walking around. Antiquity and modernity are dialoguing on the wooden panel.

The model for the face is the same he used for the face of God of his cycle in Arezzo, and he painted it all before painting the beard over it. Because the guy was insane.

Next to his feet, there’s a hint of a porphyry pedestal, and scientific investigations revealed traces of a blue, feathered wing above his head, later painted over, but more on that later.

Saint Michael the Archangel

He doesn’t look bothered, and yet he’s just done killing the snake. Saint Michael holds a semi-transparent sword and it’s strangely attired, isn’t he? He’s the missing piece between poverty and splendour, between past and present. He’s dressed like a Byzantine warrior, just when negotiations had opened between the Roman Church and the Oriental one. And if you don’t see the politics in it, you’re just trying not to see it.

Besides, his red shoes are what got me into the crowded exhibition, as I was wearing something similar.

If you look closely, you’ll see a piece of a stone basement that’s similar to the one next to the right foot of Saint John and, this time, there’s also a drape of a decorated cloth. Underneath, as Piero painted everything even when he knew he was going to cover it up, apparently there’s a foot. And traces of a pink, feathered wing above Saint Michael are even more evident than the blue one on the other side. So what was in the middle?

The missing central piece

The video in the other room will show you the scientific evidence and, with cold composure, it will give you the solution. I was lucky enough to follow the passionate explanation offered by the museum, and that’s not how it goes.

What’s standing in the middle of a composition, enthroned, with two angels at each side? Well, a Virgin Mary with Child, of course.

Except what’s left of the basement is porphyry, and Madonnas only seat on white marble.

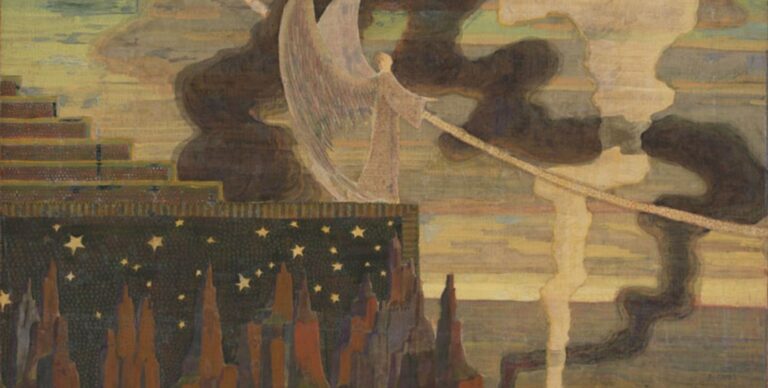

A dark-red stone, porphyry is generally used for Emperors, and this gives us the only plausible answer: the scene was an asymmetrical coronation, with the Virgin kneeling on the left and Christ enthroned who was crowning her on the right. What’s left of this scene is two shreds of wings, a piece of cloth and two blocks of stone. The rest, you’ll have to guess.

1 Comment

Pingback:Shelidon | Andrea Solario, at the crossroads of Realism and Reinassance

Posted at 10:07h, 13 May[…] The Poldi Pezzoli Museum, a hidden gem among Europe’s most enchanting house-museums, dedicates to him a jewel of an exhibition titled “The Seduction of Colour: Andrea Solario and the Renaissance between Italy and France.” Running from March 26 to June 30, 2025, it commemorates the 500th anniversary of Andrea Solario’s death, offering an unprecedented exploration of his artistic journey and—as it has been traditional for the Poldi Pezzoli museum—using scientific explorations to gain new insight into lost works. Collaborations with institutions like the CNR (National Research Council), in fact, have facilitated in-depth studies using X-rays, infrared imaging, and reflectography, unveiling new insights into Solario’s techniques and materials and finding another Madonna (do you remember the same operation done for Piero della Francesca. […]