Overlooking Piazza della Scala in the stunning building called Gallerie d’Italia, the exhibition explores the production of Giovan Battista Moroni (1520 – 1579) with over 100 paintings and drawings, also featuring books, jewels and a piece of armour. Works from Lorenzo Lotto, Tiziano, Veronese and Tintoretto are also brought in to contextualise the work of this overlooked master of his own age. I must confess I had very low expectations for this exhibition, and I was absolutely blown away.

The exhibition is divided into nine thematic sections, each one dedicated to a particular aspect of the production of the artist:

- the early days and studies, and the relationship with his master Alessandro Bonvicino, known as “Moretto”;

- his relationship with Lorenzo Lotto, particularly through his production in Brescia;

- an in-depth look at the artistical scene after the council of Trento;

- a section on people of power;

- a counterpoint section on portraits of common people in more spontaneous contexts;

- a follow-up section on portraits of powerful and notable people;

- the powerful depiction of the Catholic reform against the backdrop of the neglected poor;

- a section on prayer and the spiritual aspects of life as represented by Moroni.

Portraits, portraits and more portraits

Wait, before you run away: if portraits aren’t always boring, we owe it to this guy.

His paintings are often defined “portraits in action”, as they present characters in the instant they are performing a gesture that’s significant to identify their trade, to glimpse their personality or simply to encapsulate their views of life. He was a sober man, preferring shades of grey in his later life and making a very selective use of nature with small still lives that sometimes steal the main scene.

Here’s a section by section overview of an exhibition I strongly recommend you see with a guide, if you have the chance. If not, I’ll be your guide. Or at least I’ll try.

Moroni’s early years

Moroni entered the workshop of Alessandro Bonvicino known as Moretto when he was very young. Moretto was a Brescian painter very active in the nearby artistic centres of Bergamo and Milan, where he produced some of his most representative paintings. According to Giorgio Vasari’s authoritative opinion, Modetto’s main ability was to ‘imitate natural things’, a skill inherited by his most brilliant pupil.

The section showcases a series of drawings by Moroni this formative phase, around 1543. They are notebook sheets in which the artist practised copying his master’s models, a practice he would put to good use once he was called upon to produce the main altarpiece for the basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Trento, completed in 1551.

The level of detail and the vividness of these sketches is absolutely stunning, with hands and feet and robes and beards inked as if they were jumping out from a modern comic book.

Following in Lorenzo Lotto’s and Moretto’s Footsteps

Moroni’s earliest portraits date from the fifth decade of the 16th century. In these experiments, he was certainly inspired by Lorenzo Lotto, alongside his master, as the two were close friends, so much so that when Lotto decided to leave Bergamo after a ten-year residence he recommended Moretto do his patrons who wanted a portrait.

Moroni appreciated Lotto for his extraordinary ability to adopt an informal and disenchanted approach, capable of establishing a special relationship with the subject portrayed and surprising him in his most secret intimacy.

My favourite painting from this period certainly is the guy with the statue, the Portrait of Marco Antonio Savelli from 1543. The work was mistaken for a painting by Tiziano, and it’s still traditional witth the inclusion of classical art at the background. Rarely he would indulge in these touches, when it comes to his later works, but I kind of like it.

Moretto provided his pupil Moroni with layouts perspective tricks that would allow him to focus on the physical appearance of the models, on their faces and on the shades of personality that could be communicated through their gazes. Lotto provides examples of natural settings and poses supporting the insight on the portrayed figure.

Moroni in Trento

The city of Trent hosted an ecumenical council of tremendous impact, initiated in late 1545 to face the spreading reformation. At that time the city’s prince-bishop was Cristoforo Madruzzo, a personality of recognized diplomatic skills linked to Emperor Charles V.

Moroni had come into contact with the Madruzzo family by making portraits of Cristoforo’s grandchildren, and that’s how he met the sculptor Alessandro Vittoria, another artist who had the Madruzzo family as patrons.

Vittoria is recognised as one of the masters of mannerist sculptors, and his masterpiece is considered to be a Saint Sebastian in the Montefeltro Chapel at San Francesco della Vigna in Venice.

His portrait is showcased in the exhibition next to Tiziano’s Portrait of Giulio Romano, who proudly shows the plans for one of his architecture.

Tiziano used to tell chancellors in Bergamo that, if they wanted a portrait, they should have asked Moroni, as he would paint them natural.

— Carlo Ridolfi, 1648

The Council brought an international atmosphere in Trento, and Moroni could gain familiarity with the latest tendencies in portrait paintings, from Tiziano to Anthonis Mor. At the time, both artists were laying the foundations of what would be called “state portrait”, a type of solemn portrait that seeked to both capture physognomic features and restitute the character as if they were out of time.

Anthonis Mor in particular was a Dutch who had been introduced to Charles V by his patron, Cardinal Granvelle of Arras. His most famous work is the portrait of Mary I of England.

Potraits of Power

During the sixteenth century, people of power made extensive use of portraits, meant to convey their stature and personality across Europe. Moroni painted mainland podestà from the Venetian patriciate, for instance, but rather than conveying the gravity of their rank and the decorum of their status, Moroni brought out more confidential and familiar aspects, through portraits that introduce us into their private sphere rather than celebrating their public one.

The most stunning painting in this section is the Portrait of Giulio III, inherited by Innocenzo del Monte who tasked Moroni to paint himself into the painting, next to the pope, and the two works had recently been separated. I have no idea how they did it.

Their story isn’t a particularly edifying one, as it’s considered one of the biggest homosexual scandals in the history of the Catholic Church.

Giovanni Maria del Monte had met 13-year-old Santino a few years earlier than becoming pope. He was the son of one of servants, and the cardinal fell madly in love with him, buying the connivance of the boy’s father with substantial favors. As a reward, the boy obtained ecclesiastical benefits at age fourteen and was eventually adopted by the Pope’s brother Baldovino who named him Innocenzo.

Four months after becoming Giulio III, he appointed Innocenzo vice-chancellor of state, head of the entire governmental structure. Historians close to the Vatican downplayed the scandal by saying that he appointed “a nephew,” and appointments of nephews as cardinal vice-chancellor in Rome were perfectly normal in a situation where the first concern of any new pope was not to get poisoned. Innocent’s appointment as cardinal however elicited protests from the cardinals who were most sensitive to the need of reforming the customs of the Church to counter the Protestant Reformation. The Council of Trento was in full swing, at the time, and Innocenzo’s appointment created much clamour in some of the European courts.

Since the boy always accompanied the pope carrying his monkey, a rumor was circulated around Rome in the attempt of explaining such an appointment as a reward for this task, and of the fact that the boy was the guardian of an animal that was much loved by the pope, but the theory didn’t stick. The boy was nicknamed “Bertuccino”, and satyrical poems were circulated in which it was suggested that the Pope loved both the monkey and the monkey carrier, and he should have made cardinal the monkey as well.

Groomed by the Pope, Innocenzo grew to be less than innocent: at the age of 23, after the death of Giulio III, he was involved in violent incidents, rapes, rapes, and murders. Pope Paolo IV stripped him of his rank and eventually exiled him in Bergamo, where he met Moroni and asked for the painting.

Giulio III and Innocenzo are buried together in San Pietro in Montorio.

“Natural” portraits

“Since they’re called ‘natural’ portraits, one will put greate care so that the face or other part of the bodies aren’t made more handsome or more solemn.”

— Gabriele Paleotti (1582)

The naturalism of Moroni’s paintings is the result of a technical strategy: the figures are in fact presented in a life-size format, with their proportions carefully respected, so that the viewed can have the illusion of standing in front of the real subject. The painter also wasn’t used to sketch the subject and painted straight away, which makes these works more luminous and vibrant. Physical defects are welcomed, in this scenario, as they increase the sense of realism and often add to the personality.

The section also features two very rare paintings of women: one of them is preserved at the Uffizi, they don’t want us to take pictures of their precious crusts, so we won’t even talk about it.

The other one is damn fine: the red-haired Luisa Vertova Agosti sports tight curls and an even tighter hairstyle, with two flowers above her ears and a dress in black and white that seems to spring out of a Flemish painting.

Two of the finest works in this section are the profile portrait of Bartolomeo Colleoni and the frontal portrait of Giovanni Gerolamo Albani, a jurist named cardinal by Pio V in 1570, and one of the fiercest hunters of heretics across northern Italy. It’s almost as Moroni painted the cyst on his forehead to represent the shit coming out of his head.

Altarpieces with and without portraits

During the long rule of Federico Cornaro as bishop of Bergamo (1561 – 1577), the artistic and intellectual climate was oriented toward an obedient proclamation of loyalty to the principles dictated by the Council of Trent. Diocesan parishes quickly established themselves as important patrons of Moroni, who was called upon to replace old devotional images with a repertoire that updated worship art to contemporary forms and sensibilities. Public commissions intensified in coincidence with the apostolic visitation of Carlo Borromeo in 1575, as they wanted to look cool in front of the contemporary superstar.

Before the Council of Trento tried to tone down the self-celebration and corruption, it was customary for patrons to include their portraits in altarpieces, worshipping the saints or being blessed by them. They were propaganda pieces.

After the Council, the presence of such portraits on altars began to be frowned upon as it should have been from the beginning and as I’m sure people were already doing before the Council said so.

In Moroni’s altarpieces, we find portraits of diocesan priests intent on charitable acts or celebrating the Sacrament of the Eucharist, which protestant reformation was declaring to be superstitious nonsense.

I’m not too fond of religious subjects, as you might imagine, but there are some stunning pieces in this grand section, and you might want to take a look at the so-called Pala Rovelli (above a detail), recently restored to its former glory.

It depicts a glorious Virgin Mary with a flowing white veil that’s exquisite in all aspects and a caring Jesus child softly caressing her cheek. On the left part, Saint Nicholas from Bari receives his traditional emblems. That’s before he became Santa Claus.

To complement the altarpieces in the room, the exhibition shows a piece by Lorenzo Lotto, The Alms of Saint Antonius from around 1540.

The Portraits of Society

Members of the leading families of the time up in Bergamo hired Moroni because of his recognized specialization in the portrait genre. The painter had moved back from Trento to Albino, his hometown, and he did so many portraits during this time that they give us a clear photograph of the society of his time.

The only personality Moroni paints on more than one occasion is, extraordinarily, a noblewoman, Isotta Brembati. Celebrated poet married to a Spanish nobleman from Aragona, she was known for her compositions in Italian, Spanish and Latin. One has to love her ostrich-feathered fan in the colours of the trans pride flag.

The most important painting of the section is, however, considered to be the Portrait of Gabriel de la Cueva, viceroy of Navarre and future governor of the State of Milan, represented in full armour and the corresponding Knight in Pink.

The Devotional Portrait

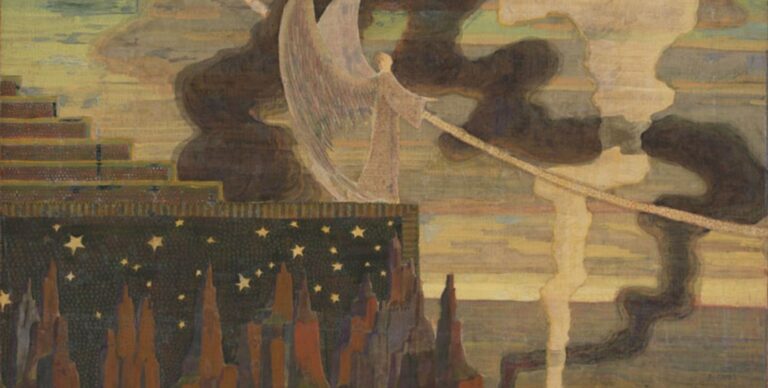

The two main genres depicted in the exhibition — portrait and religious painting — come together with the genre of the devotional portrait, a concept coming down from the silent prayer as described by Ignazio di Loyola in his 1548 Spiritual Exercises.

In his view, meditation happened through the “mental composition” of an imaginary place meant to soothe and aid contemplation. It’s only natural that Moroni melts the limit between the real and the imagined, showing dream-like environments as they were springing from the mental exercise of the character portrayed.

The Tailor and black is the new black

The exhibition concludes with Moroni’s masterpiece, the portrait of a simple tailor, where a man is shown with the tool of his trade while he cuts a piece of black cloth.

During the reign of Charles V, black became the official colour of the court of Spain, quickly spreading through the rest of Europe as fashion trends do.

Moroni faithfully reflects this trend through his many portraits in black, a genre that allows him to push the limits of his technical mastery.

“Tell me whether in your opinion there is a more distinguished, and more refined, as well as more genial portrait in the world than Moroni’s Man in Black. You will see it was not by any means Whistler who invented tone”.

— Bernard Berenson, 1895

No Comments