As I anticipated, I’m looking into Lafcadio Hearn’s Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things. The first story collected in the book revolves around a prominent figure in Japan’s folklore, Hōichi the Earless (耳なし芳一, Mimi-nashi Hōichi), a cursed bard. It is normally considered that Earn wrote his tale after reading Isseki Sanjin (一夕散人), and his 1782 work “The Secret Biwa Music that Caused the Yurei to Lament” (琵琶秘曲泣幽霊, Biwa no hikyoku yūrei wo kanashimu), in volume 2 of Gayū kidan (臥遊奇談). The full version of Hearn’s text can be red here. There’s a beautiful in-depth analysis here, and another good post is here.

1. The Story

As the story goes, Hōichi was a blind minstrel, extraordinarily versed in playing the biwa but almost as extraordinarily poor: he lived in the Amidaji Temple, under the protection of a friend monk. His strongest point was the Heike Monogatari, The Tale of the Heike, an epic account of the fight between two rival clans: the Taira and the Minamoto.

Serizawa Keisuke, frontispiece of the Heike Monogatari (1960)

One evening, he was approached by a Samurai who required him to come and play for his lord and his court.

Hōichi wasn’t supposed to get out of his temple at night, but the invitation was too tempting, so he took up his lute and followed the samurai.

Once he started playing in front of the daimyō, the tale of the two fighting clans touched the hearts of the people at court and the performance reaped great success: the audience was moved to tears, the daimyō was extremely happy with the recital and asked Hōichi to come back the next evening in order to perform again. The samurai however warned the minstrel that the daimyō was travelling incognito and forbade him to speak a word about the event.

As you might imagine, it’s borderline impossible for a guy to keep a secret, even in ancient Japan, and Hōichi’s nighttime absence is noticed by the priest of the Amidaji Temple where the bard resided. The priest instructs a servant to follow the minstrel in his wandering and, to his surprise, all they see is the guy playing his biwa in the middle of the Amidaji cemetery.

And everywhere above the tombs,

the fires of the dead were burning,

like candles.

When he is dragged back to the temple, Hōichi has to tell the tale of how he performed in front of an audience that was captivated by his words, and how the invitation to go and perform repeated, night after night.

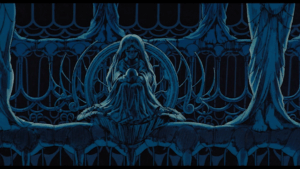

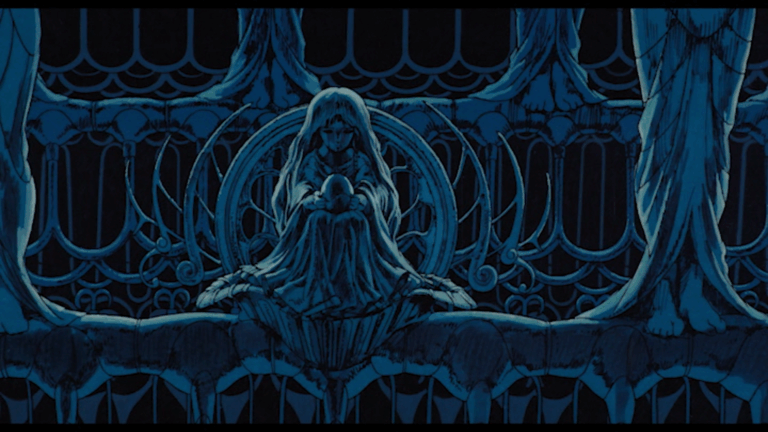

At this point, the priest has no doubts: his fellow monk is being bewitched by ghosts. In order to protect him, he paints Hōichi’s body with the kanji characters of the Heart Sutra, a famous sutra in Mahāyāna Buddhism.

Form is emptiness,

emptiness is form.

He then instructs the bard, should the ghosts appear again to summon him to their court, to remain silent no matter what.

When the samurai appears again, the following night, the minstrel stays completely silent and still, as instructed, and the ghost of the warrior gets angry at receiving no response. All he can see of the monk, however, is the only part of his body not covered in kanji: his ears. In an attempt to fulfil his master’s command, he grabs Hōichi by the ears and rips them off, taking them back to his master.

Regardless of this injury, this frees him from the ghosts’ influence and Hōichi lives on to become a famous musician.

Illustrations

The original edition of Lafcadio Hearn is absolutely awesome, and there are some pictures here.

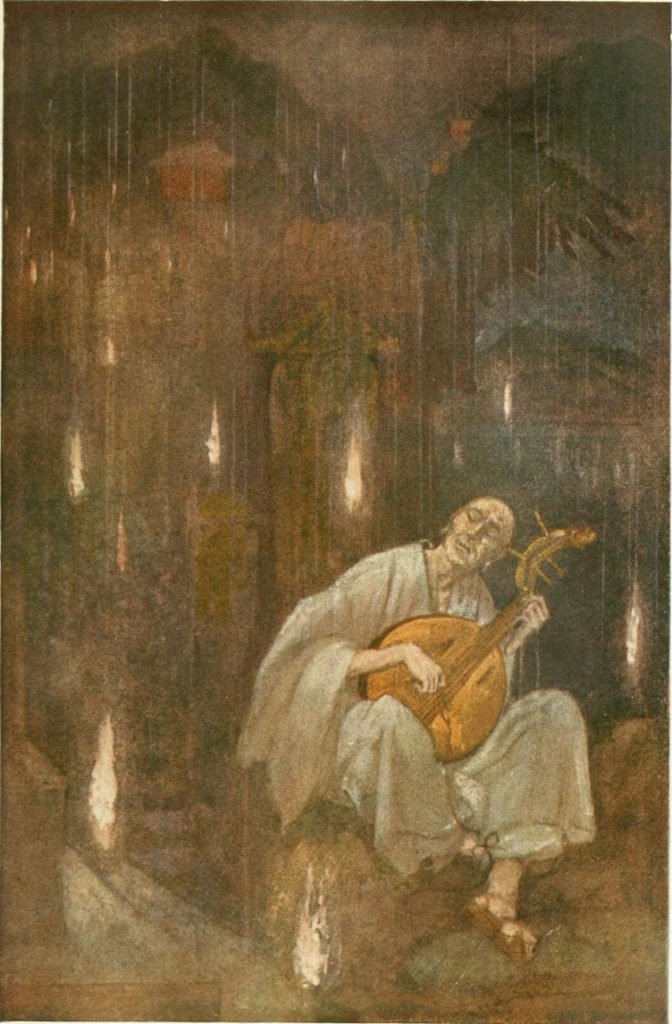

Among them, an original sketch of this very story, in which we see Hoichi playing the lute in the cemetery.

Lafcadio’s work was originally meant to be illustrated by his son, Kazuo Koizumi, who worked on several watercolours to accompany the text. Some of them can be seen here. They are collected in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library and they’re not all publicly available. My favourite has to be this one:

Hearn’s work was then republished a couple of times with illustrations and I did my best to track down the different artists who tried their hand at this.

In 1921, Emil Orlik illustrated Kwaidan alongside some other works by Hearn, all published in Vienna and you have a list here. His style couldn’t be more in line with the Vienna Secession, with its geometric patterns, and screams Klimt from every twist and twirl.

In 1966 a monographic edition of this tale was produced and you can see it here. It includes beautiful illustrations by Masakazu Kuwata, and you can get a glimpse of them on the website I linked. My favourite has to be the frontispiece of the book, with the minstrel playing surrounded by flames, but the whole thing looks absolutely stunning.

In 1974, the Merlin Gardyloo Press in San Francisco published a limited edition with illustrations by Cathy Pollack, but it includes only the tale Mujina, so we’ll talk about her in another moment if we get to that. If you’re curious, you can take a peek here.

A contemporary artist you might wanna take a look at is Shiro Ohara, who worked on a set of four illustrations based on Lafcadio Hearn’s works, but none of them is about our favourite earless musician. Kelley McMorris also illustrated the scene of the bard playing, surrounded by the flames of the dead, and you can find her page here. She did a couple of versions of this scene and another can be seen here.

This much more gory illustration of Hoichi’s ears being ripped out, on the other hand, is credited to Suehiro Maruo, and I love how the cemetery is depicted in the distance, with the fire returning to its grave.

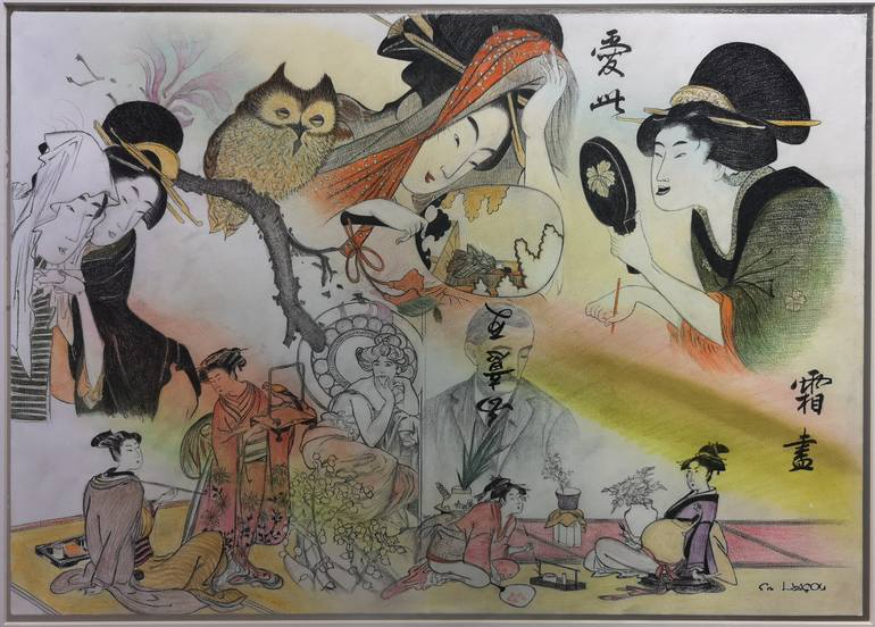

On a more general note, please check out this work by Emmanouela Liagkou, a painting that renders homage to the author and his life.

Lafcadio Hearn is not, however, the only author to talk about the tale of the earless musician. Frederick Hadland Davis published his own take on Japanese legends in 1913, with beautiful illustrations by Evelyn Maude Blanche Paul, a wonderful illustrator (and Paul is her surname, in case you’re wondering). If you are not from Italy, where the site is blacklisted because we’re stupid assholes, you can read the book at Project Gutenberg, here.

The tale also features in a book I already talked about in my 2021 Winter Tales collection: Tales of Japan – Traditional Stories of Monsters and Magic, with original illustrations by Kotaro Chiba. In that, we have one opening illustration, with the monk depicted from the back in his iconic pose, the same we see in the famous statue (see the section about the places of this tale).

2. Themes: the Fires of the Dead

One of the scenes that most captivated artists, as you have seen, is the scene where Hōichi is playing in the cemetery and the fires of the dead are competing with the pouring rain around him.

This kind of creatures are often described as Onibi (鬼火), though there are other two creatures of fire that are associated with the spirits of the dead: the Hitodama (人魂), which are fires originated from the recently deceased, and the Kitsunebi (狐火), an atmospheric phenomenon.

The Wakan Sansai Zue, an illustrated encyclopedia published in the Edo period (1712) compiled by Terajima Ryōan (寺島良安), presents us with an illustration of the Onibi as balls of fire that are raining from the sky.

There are different names for these creatures, however, and different areas might apply slightly different characteristics, as it often happens with Japanese creatures.

- in the Kōchi Prefecture, the creature is called Asobibi (遊火) and it mostly appears below castles and above the sea: its name means “play fire”, it has the habit of flying around and divide itself and is generally harmless;

- the Watarai District of the Mie Prefecture calls this creature Igebo;

- in the Ibi District, Gifu Prefecture, we find the Kazedama (風玉), which name means “wind ball”;

- in the Okinawa Prefecture, the Hidama (火魂) is a ball of fire that lives in fireplaces behind the charcoal extinguisher but can also turn into a firebird and fly around the house, causing things to catch fire;

- in a specific village of the Kitakuwada District, Kyoto Prefecture, the Wataribisyaku (渡柄杓) or “transversing ladle” is an Onibi that appears in the form of a hishaku, the ladle in the Japanese tea ceremony.

There are also particular kinds of onibi, with specific characteristics, like the Inka (陰火), which name means “shadow fire”, which appears when a ghost or a yōkai is summoned or shows up.

There are also some literarily famous Onibi, such as the one featured in Konjaku Gazu Zoku Hyakki by Sekien Toriyama (1779): in a retelling of the famous ghost story Banchō Sarayashiki, the main character appears as a shadow fire, but is depicted in the peculiar activity of counting plates and is therefore called Sarakazoe (皿数え), which means “count plate”. Another famous and named Onibi in the same collection of tales is called Sōgenbi (叢原火) and it’s the ghost of a monk who was transformed into a fire as punishment for stealing.

Last but not least, we have the Kitsunebi (狐火) or Fox Fire, connected with the extreme fascination Japanese folklore has for these creatures.

The most famous illustration of Fox Fires has to be the 1857 plate by Utagawa Hiroshige portraying a sabbat of foxes at New Year’s Eve.

In 1859 with his Comical Views of Famous Places in Edo he came back on the subject with his Fox-fires at Ôji (Ôji kitsunebi), with a strikingly more amusing depiction of the foxes in procession.

We don’t know which kind of fire is visiting this woman in this 1859 print by Utagawa Kunisada, but one can only imagine it’s not a natural fire, as natural fires rarely pay you a visit while you’re taking a stroll with your fancy umbrella. This particular version I’m presenting is preserved at the Tokyo Metro Library but you also have other copies in the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria and in the Waseda University Theatre Museum.

If you like this but you want something more dramatic, you have to wait until 1898, when Toyohara Chikanobu creates this amazing triptych called The Fire Flashes (thanks, Japanese Art Open Database): in this scene, you have a woman dancing beneath a rain of firebolts, holding a devil mask, with two rather puzzled gentlemen at the sides. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where a copy of this drawing is preserved, the scene is the Kitsunebi Scene from the play Honchô nijûshikô. The Waseda University Theatre Museum also have enlargements for the two unfortunate guys at the side.

Coming back to the more traditional Onibi, there are some awesome illustrations made by Matthew Meyer in his yokai encyclopedia, like these fireballs raining on marshy land, which would be perfect for #SwampSunday (if you don’t know what that is, go check it out).

He also has a nice one of the same fires raining on some sort of riverside, which is particularly charming because of the little detail of a skull, half-buried in the sand over there.

If you’re looking for a close-up, there’s also another version with a single fireball (you can see it here), but the most fitting for our tale would be the one with fireballs dancing in a graveyard, which you can see here. He’s an awesome artist and his style is absolutely iconic.

3. The Instrument

The biwa is a particularly shaped Japanese lute, with a short neck and a pear-shaped form. It originated in China and it’s usually made by a single piece of wood, with wooden preparations that are called “tasti” in Italian, like the keys of a piano, but I have no idea of you call them in English.

A wonderful illustration of the different types of biwa made by Gleolite for Wikimedia

It originated in China as a plucked instrument, but in Japan it’s played with a tool (with variations that you see represented above) called a bachi, a term that comes to indicate both the wooden sticks used for drums and the wooden plectrum used for strings.They were usually made out of ivory or tortoiseshell, but today of course they’re made of wood, plastic or acrylic. As they should.

The Asian Art Museum of San Francisco preserves a beautiful netsuke in the shape of a biwa, in which you can also see the detail of the bachi stored beneath its strings.

What’s odd is that the biwa is almost specializing in telling the Heike story: originally used by monks to accompany themselves in the reading of the scriptures, blinds monks called biwa hōshi started turning into minstrels. In that regard, the story of Hochi the Earless is not only the off story of a monk’s encounter with ghosts of the Taira family, but also the story of how these minstrels were born.

4. The Setting

The story is set in an actual place: the Amidaji Temple at Akama-seki, in what was known as the Chōshū Domain. By confronting Hearn’s version with previous texts, the place was identified as today’s Akama Shrine in Shimonoseki, the largest city in Yamaguchi Prefecture at the lower tip of the bigger island of Japan (Honshu).

The shrine is dedicated to Emperor Antoku, the child-emperor who was killed during the struggles between the rival clans of the Taira and the Minamoto, struggle at the centre of the Heike Monogatari. His birth was a troubled one, as his mother Taira no Tokuko was believed to be ill because of his grandfather’s crimes. He was only 2 years old when he ascended the throne, in 1180, and “reigned” only for five years, before being drowned by his grandmother Taira no Tokiko who was escaping capture by the Minamoto and preferred committing suicide and murdering the child with her.

In the legend, Antoku’s grandmother wishes for their palace to be created under the water, before jumping into the sea to her death, and therefore they are both transported to Ryūgū-jō, the underwater palace belonging to the shape-shifting water god Ōwatatsumi. After their death, his mother Taira no Tokuko has a dream in which her son and her mother are indeed living in that underwater palace.

Anyway, after his death, several shrines were built in his favour and he later came to be worshipped as a water-god (Mizu-no-kami), but his actual burial site is debated and one of the hypothesis include the island of Iwo Jima, allegedly leading to contemporary legends of his involvement in the famous battle.

The Akama Shrine can be visited up to these days and has a shrine dedicated to our favourite earless minstrel. The geographical aspects of the tale are well covered in a nice article at Tsemrinpoche.

5. The Heike Monogatari: the tale within the tale

There’s a part I have omitted in the tale, but you might have guessed it from the level of engagement the ghosts showed with the tale Hōichi was singing: those were not just any ghosts, but they came straight from the Heike Monogatari, the tale Hōichi was singing. So what’s the tale about? We will see it next week. Meanwhile, I leave you with some of the amazing artworks this epic has inspired.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, “Jô Shirô Nagamochi of Echigo Province, going to War for the Taira, sees an apparition in the sky” (1849-1852)

No Comments