Lucretia is one of the most famous women of Roman tradition, a noblewoman whose suicide (again) prompted the overthrown of the Roman monarchy and the birth of the Republic.

Her story is narrated by three main sources: Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Ovid and Titus Livius. Our favourite is, of course, Ovid.

As the story goes, Lucretia was the daughter of a magistrate, Spurius Lucretius, and the happy wife of Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus, nephew of the fifth King of Rome. She is described as the embodiment of the Greek virtue sophrosyne, an ideal of temperance, moderation, prudence, purity, decorum, and self-control.

All this virtue, unfortunately, attracts the attention of an asshole, Sextus Tarquinius, son of Lucius Tarquinius Superbus who – spoiler alert – is going to be the last king Rome will ever have.

Tarquin Junior, the asshole of our story, was being sent around by the king his father, because that’s what princes do, and was received at Lucretia’s house with great honours, but thought best to infiltrate the lady’s quarters during the night.

He threatened her not only to kill her, because that wasn’t going to be enough, but to sully her good name by placing a slaughtered slave next to her and saying he had caught them in flagrant adultery.

Since Roman society would teach you to value your virtue and good name above everything else, he thus was able to extort her consent.

The details of her suicide vary between the accounts of Dionysius and the one of Livy, but they both agree on the fact that she went to her father and her husband, requiring them to call witnesses, and denounced her aggressor.

In ancient Rome, apparently, it was obvious enough that «it is the mind that sins, not the body, and where there has been no consent there is no guilt». Maybe we should remember that nowadays as well.

After receiving the solemn promise that she will be avenged, but being unable to live with her honour tainted, she then drew a dagger and publicly stabbed herself.

This scene, and the act that had led to the noblewoman’s tragic deed, outraged the Roman people and the corpse of Lucretia was paraded around the city up to the Roman Forum, where it remained on fucking display while the revolution raged.

Lucretia’s husband, Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus, was to be one of the first two consuls of the newly formed Republic with Lucius Junius Brutus, one of the two witnesses of Lucretia’s suicide according to Livy.

It’s significant that, just as it happens with the foundation myth, the second most important transition in Roman power is explained through a story of sexual assault, just as it happened with the rape of the Sabine women.

Lucretia is a very popular character and, alongside Cleopatra, probably one the most popular women featured in Madame De Scudery’s work. Her story, following Livy, is also narrated in Geoffrey Chaucer‘s The Legend of Good Women, which also features Cleopatra, Thisbe, Dido, and Hypsipyle.

Drawing from Ovid, William Shakespeare also dedicated her a long poem called The Rape of Lucrece (probably composed in 1594) and often uses her name as a rhetorical feature to mean virtue: she’s mentioned in Titus Andronicus, in As You Like It, and in The Twelfth Night, and she also refers to her in Macbeth and Cymbeline.

Madame De Scudery has Lucretia writing to her husband.

1 Comment

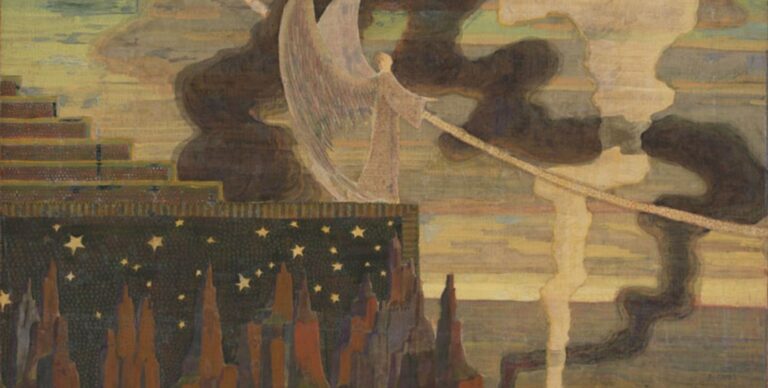

Pingback:400 centuries of folding screens – Shelidon

Posted at 00:03h, 22 November[…] by his wife Jane Morris. The subjects of the screen are three heroines: Lucretia (I wrote about her here), Hippolyta queen of the Amazons, and Helene of Troy. The three women embody three different sides: […]