It was high time to go, for the pool was getting quite crowded with the birds and animals that had fallen into it: there was a Duck and a Dodo, a Lory and an Eaglet, and several other curious creatures.

Last week, we fell with Alice in her own pool of tears and made our acquaintance with a quite anxious rat who has a story to tell.

This is the first coloured illustration Arthur Rackham decides to give us, following the full figure of Alice, with our girl swimming alongside a rat, a pelican, a crab, a very anxious-looking goose, a crow and what looks like a beaver, with the dodo peeking from the top-left corner of the frame.

It is rather rare for illustrators to show us this scene, as mostly they focus on the following chapter with the caucus-race and the mouse’s tale. To get pictures of this scene, we have to turn to those illustrators who, like Rackham, have a knack for showing us scenes that are either not central to the narration or, sometimes, not even there. It’s the case of Charles Robinson, if you remember: one of the few illustrators to show us the secret garden on the other side of the small door in chapter 2.

He gives us a rich illustration, with a flamingo and the dodo, a parrot and a pelican, an owl, some other weird exotic birds and a snail.

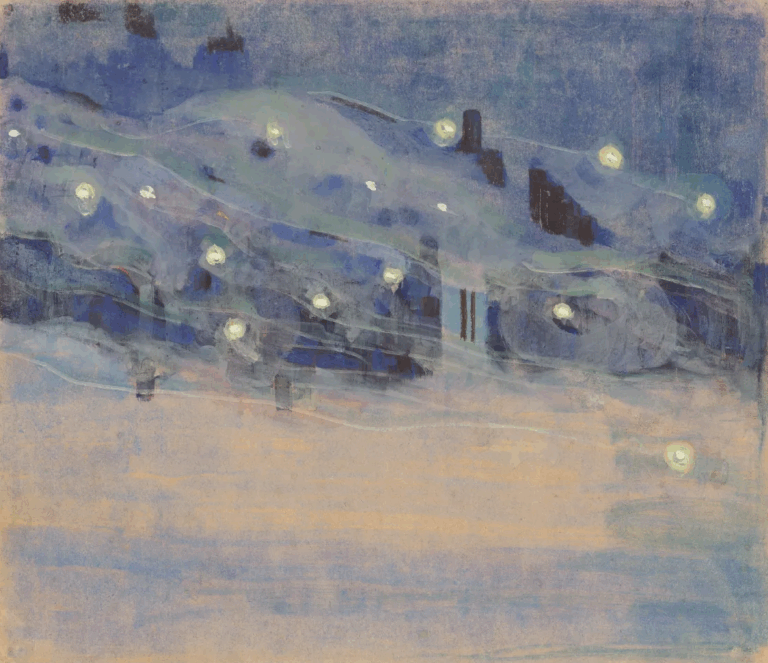

If you’re looking for something a bit more surreal, Moritz Kennel illustrated an edition of Alice in Wonderland that was published by Phaidon in 1975 and his work is very particular. For this specific scene, he gives us a swimming Alice, with a hat shaped like a paper boat, aided by a rather large eagle.

The same set of animals we see in Rackham’s picture is picked by Peter Weevers and it’s also the cover for the Hutchinson edition he illustrated in 1989. You can see it here, although it’s already sold.

We have already met Weevers with his falling Alice but especially with his crying Alice on top of a crispy pool of tears. If you like him, I suggest you try and grab a copy of Herbert Binns And The Flying Tricycle, a delightfully illustrated story by Caroline Castle in which a clever mouse is trying to invent a flying machine.

A few years later, another artist to work on the subject was Mabel Lucie Attwell, a beloved artist who is unfortunately plagued by a bunch of people who put watermarks on her work although not owning it. There’s a specific circle of hell for people claiming ownership to stuff they do not own.

Some copies of the edition she illustrated can be seen here.

In the 90s, one of the most charming contributions has been done by Angel Dominguez, who strangely enough decides to give us a walrus and a hippo in what looks more like a flowery pond than a pool of tears but definitely is one of my favourite illustrations. Dominguez published his edition with Workman Publishing, in New York, and followed up in 2015 with a limited signed edition of Through the Looking Glass, this time in Great Britain with Inky Parrott Press. You can read a beautiful article and see some pictures here.

Among contemporary artist, we find again the West German-born American artist Kiki Smith (we have already encountered one of her works for the Pool of Tears) with a rather anguished Alice and a wonderful choice for a completely non-transparent water that only adds to this feeling. The work is her second take on the subject and was apparently exhibited in the “I won’t grow up” exhibition in 2008, curated by Beth Deewoody. If you want to read more about this artist, I suggest this article (though it’s in Spanish).

Emma Chichester Clark, a contemporary illustrator we already met for falling Alice, gives us her dark-haired, blue-dressed character whit floating in the pool, surrounded by animals, in a strangely apathetic attitude and the face of one who’s clearly not up to the amount of bullshit she’ll face from here on. The article dedicated to her on the “Draw Me” blog suggests that her Alice is inspired by the Madeline franchise, a series of children’s books written and illustrated by Ludwig Bemelmans.

Another cool contemporary illustrator who did a fascinating interpretation of the Pool of Tears is Kirtsy Greenwood (not to be confused with the romantic comedy author) and it was on sale here. She also did a “Down the Rabbit Hole” and “Caterpillar”.

One of the most visual striking works done on Alice for the 150th anniversary, although a bit disturbing, was done by Benjamin Lacombe and he chooses to illustrate the scene from underwater, with an Alice that seems to be more drowning than swimming, and the curious looks of fancy-clothed creatures that is partly worried (the Dodo), partly curious (the owl) and partly murderous (the mouse).

A more recent one is this pencil illustration by Christian Birmingham, done for an edition by Books Illustrated in 2019.

On his website, you can find an Alice in Wonderland gallery with lots of works done on the subject, including a cheerfully falling Alice, one inspecting the “drink me” bottle in a rather gothic hallway, and a very fancy mouse swimming with Alice.

Getting Ashore

Among classical illustrator showing us the bunch of animals (and Alice) getting ashore, a peak position is occupied by Fanny Y. Cory, one of the first illustrators of Alice in 1902.

Alice led the way

She also shows us a very wet Alice with the mouse once they got ashore.

They were indeed a queer-looking party that assembled on the bank—the birds with draggled feathers, the animals with their fur clinging close to them, and all dripping wet, cross, and uncomfortable.

Of all these characters, however, the first we make a proper acquaintance with is the Dodo, one of the most illustrated creatures in the section and one in which, allegedly, Carroll put a lot about himself as well. So, let’s start from him.

The Dodo

According to Martin Gardner, author of the Annotated Alice, Lewis Carroll often went to the Oxford University Museum with the Liddell children, including Alice Liddell herself. when the group was visiting, the infamous flightless chicken had already been extinct for around 200 years (Alice came out in 1865, the dodo went extinct in 1681) and the museum preserved both a skeleton and the famous painting by Dutch painter Jan Savery.

The Dodo was intended by the author as a caricature of himself: the author stammered, apparently, and his original surname – Dodgson – was often mispronounced “Dodo-Dodgson”. When the first edition of the manuscript was published in 1886, a friend received a copy with explicit dedication: “The Duck from the Dodo”: the friend incidentally was Reverend Robinson Duckworth, who often accompanied Carroll on boating expeditions with the Liddell sisters, and he’s inspiration for the duck. The whole segment has autobiographical tones and reflects some adventures of the party, messing around in boats as some would say: the Lory, an Australian parrot, is Lorina, the eldest of the sisters (and this is why she says to Alice, “I’m older than you, and must know better”).

Edith Liddell is probably the Eaglet.

This is also the reason why a not central character like the Dodo is portrayed in the Lewis Carroll memorial Window in Daresbury Church, in the very first panel of five.

In memory of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson

(Lewis Carroll)

author of Alice in Wonderland.

‘What I was going to say,’ said the Dodo.

The dodo is often portrayed in a very serious manner, starting with Tenniel who portrays him with a walking stick and his illustration is kind of freaky the minute you realize Tenniel also gives the Dodo tiny creepy hands.

“But she must have a prize herself, you know”, said the Mouse.

“Of course”, the Dodo replied very gravely.

Rackham also does the same, but somehow manages to be less disturbing in deciding to get rid of the wings altogether.

Other illustrators, like Brinsley LeFanu, more sensibly decide to portray the handshake by leaving the poor Dodo with his useless wings, instead of giving him creepy hands.

Another one who manages to be less creepy than the average is Gertrude Kay, where the hand slides out from under the Dodo’s wings as if he’s wearing a coat of some sort. Not ideal, but ingenious nonetheless. Instead of the handshake, this is the scene where the Dodo gives Alice her “prize”.

The same scene had previously illustrated also by Margaret Tarrant (1916) and it always amazes me how little known her work is: she’s extremely clever in working around the Dodo’s legs, because no one ever said he had to give Alice the prize with his wings.

Sometimes, the Dodo get nautical attributes like a tricorne or a pipe. Disney’s movie goes in this direction and of course many illustrators followed.

Though I’m not fond of pastel, reassuring versions of Alice and I find the Disney version to be way too mild in this, some of these later works are really good.

The Caucus Race

The whole group comes together in two circumstances: when they’re racing and while the mouse is telling his tale.

First it marked out a race-course, in a sort of circle, (“the exact shape doesn’t matter,” it said,) and then all the party were placed along the course, here and there. There was no “One, two, three, and away!” but they began running when they liked, and left off when they liked, so that it was not easy to know when the race was over.

The term caucus race of course doesn’t have anything to do with physical racing and is another touch of satire: caucus is a preliminary meeting in which a political party tries to nominate candidates for public offices or to be delegates in meetings and gatherings, and we talk about caucus race when this appointment requires a vote between already selected members. It’s a little bit like a primary election, without the public vote.

Of course it makes sense that the Dodo runs it like a merry-go-round, and no one wins at the end. This political sense is lost in some translations, including the Italian one.

This is one of the most dynamic and nonsensical scenes of the book and it’s one illustrators tend to pick gladly. It’s the case of Maria Kirk, below, that decides to see the scene from a slightly elevated perspective.

Eunyoung Seo, a wonderfully talented illustrator from South Korea, decides to give us an Alice with her hair constantly up, a yellow-cowled dodo and an owl in his bathing suit.

On her website, in the gallery section dedicated to Alice, there’s also a lovely scene of the animals all wet in their fancy clothes, and of a rather shy mouse telling his tale.

Emily Carew Woodard, who also worked on Alice for its 150s anniversary, gives us a race in which she decides to get out of anatomically troubling details by giving both the lobster and the dodo small green shoes. As I previously pointed out, you can see all her illustrations here.

For the same anniversary, Bart Castle also worked on a caucus race that you can see here (or here on the author’s website). He’s a watermark kind of guy, and you know how I feel about those.

My favourite contemporary illustration, however, has to be David Delamare‘s who also did incredible works on the caterpillar and the tea party. The original painting is gone, but you can still buy prints here.

The Mouse’s Tale

‘I had not,’ cried the Mouse, sharply.

The page itself, in the original manuscript, is a sort of illustration with the tale being shaped like a tail (ha ha ha, very funny). It’s a shaped poem, sometimes also called concrete poetry when it’s trying to get serious.

Fury said to a mouse, that he met in the house, ‘Let us both go to law: I will prosecute you – Come, I’ll take no denial; We must have a trial: For really this morning I’ve nothing to do.’

Said the mouse to the cur, ‘Such a trial, dear Sir, with no jury or judge, would be wasting our breath.’

‘I’ll be judge, I’ll be jury,’ Said cunning old Fury: ‘I’ll try the whole cause, and condemn you to death.’

The shape was pretty much the same in the original manuscript of Alice’s Adventures Under Ground (1863), except of course, being hand-written, Carroll manages to convey a more sinuous twisting of the verses and presents the last words upside-down.

As you can see, the stories are different: in the original version, there’s just a nonsensical telling of a domestic scene, while in the printed version we get a satyr of justice and trials, and an anticipation of the subversion of justice we’ll see in Alice trial by the end of the book.

We lived beneath the mat,

Warm and snug and fat.

But one woe, and that

Was the cat!To our joys a clog.

In our eyes a fog.

On our hearts a log

Was the dog!When the cat’s away,

Then the mice will play.

But, alas! one day;

(So they say)Came the dog and cat,

Hunting for a rat,

Crushed the mice all flat,

Each one as he sat,Underneath the mat,

Warm and snug and fat.

Think of that!

Some of the illustrators decide to contribute to this page, by adding small pictures of either the mouse or the cat.

Willy Pogány for instance adds the mouse as a sort of a historiated initial and arranges the tail such as the writing can be seen as a continuation.

Ralph Steadman, for his 1967 edition, brings back a little of the fanciness of Carroll’s writing (which kind of makes sense, since we’re not printing like in the 1860s anymore). You can also see a glimpse of the animals assembling in the other page.

There’s also a version with numbers instead of words, but I could not find credits for the author (though the name of one file seemed to suggest it was by Jonathan Dixon).

Dixon for sure worked on a stand-alone version of the Mouse Tale, arranged by David and Maxime Schaefer around 1995 (you can find a used edition here).On the delightful cover for the book, the mouse is turning back to look at its tail and the tail is made of the word tail twisted around.

The same idea is reprised by Lisbeth Zwerger’s 1999 illustration, in which the whole sentence “Mine is a long and sad tale” is written along the mouse’s tail. You can find some of her illustrations in this beautiful article, in which you can also see Alice swimming in the pool of tears and the caucus race with a rather athletic rat. The book is available for purchase here. As usual, beware of the kindle version that throws you to a different edition.

Don’t be fooled by this book, illustrated by Mick Inkpen, as it has nothing to do with Alice and all to do with… Jesus, apparently.

There’s a small selection of pages here, but unfortunately no illustrator is credited and there’s no mention of the edition they came from. A much better researched and documented article is this one, where you can find two of the illustrations I mentioned.

In 1991, one Gary Graham from the University of Delaware made a curious discovery about the poem: apparently if you arrange it in the traditional stanza mode, you get the shape of an actual rat, with the last longer verse creating the tail. Carroll was not well.

Anyway, the mouse is telling his tale and John Tenniel illustrates the scene with delicacy and, though he self-copies the baboon from other satirical illustrations he did, I’m afraid I have to say this is one of the few illustrations that I find to be of my liking. I am too much disturbed by the lack of proportions for infant Alice, just like Carroll.

You can almost tell how many artist struggled in drawing the animals Carroll depicted: some of them are only drawn sideways, even if it doesn’t make much sense for the composition of the scene. It’s the case of Charles Robinson, who gives us a duck that’s clearly not interested in anything that’s going on.

A similarly arranged scene is give us by Alfred Edward Jackson, who worked on Alice for a 1915 edition and whom you might remember for the wonderful mouse jumping out of the water. You can find some more illustrations here, alongside a small biography.

Weirdly, the one to be talking seems to be the mole, and not the rat. But if you can manage to overlook that, take a look at the crow’s dress in the background, for no particular reason at all. These are the kind of details that make Jackson’s work so beautiful and yet I find he’s highly underrated.

A rather unsettling scene, on the other hand, is given us by Amy Millicent Sowerby, one of the first illustrators of the book. Her Alice is always scared or a little worried, as you might remember from her tentatively following the white rabbit, instead of rushing behind as it’s said in the book, or from her crouching and crying Alice in the hallway. For some reason that might be easily figured out, her scared and worried Alice (much like a little girl who knows what’s coming) wasn’t received well. According to the “Draw me” blog, a 1907 collective review of the many editions that came out that year wrote that her «attempts work rather too difficult for her, and she has not much imagination». I never read anybody saying that drawing children is too difficult for Tenniel and I really wonder why.

2 Comments

Pingback:The Fish and the Frog Footmen – Shelidon

Posted at 00:03h, 11 July[…] The Fish-Footman in this very livery also features on the Lewis Carroll Window in Daresbury Church, designed by Geoffrey Webb, which I already mentioned here. […]

Pingback:Lafcadio Hearn’s Japonisms – Shelidon

Posted at 00:05h, 10 January[…] a French illustrator whom I already mentioned in my Alice in Wonderland series (particularly the one post about the birds found in the pool of tears) and it’s absolutely awesome: it’s followed by a second one, less focused on ghosts and […]