The fourth and last “faction” in Barrie’s Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens is, of course, Peter. And, as I have said previously, I think he’s a fairly different character than the one we see in Neverland. This just doesn’t come down to the fact that he’s a lot smaller (seven days old) and Rackham never fails at portraying him like a baby: there’s a much more tragical tone.

Death lingers a lot in Kensington Gardens and not only because Peter turns up to be a gravedigger for children who get lost (something very far from the picaresque leader of lost boys in Neverland): he himself struggles between not growing up as a wish and growing up as a non-option. He’s a character that decides to go home, eventually, and finds his mother asleep in his own room, heartbroken. He’s also a character who’s unable to make it a final decision and goes back to the Gardens, getting lost in time himself. When he comes back to the nursery, his mother has given birth to another child and has forgotten about him. With the cruel eyes of a dead boy, he’s unable to understand and forgive his mother from moving on, and in a world where death is a liminal state, moving on cannot be seen as nothing else than betrayal.

The Piper at the Gates of… Something

One of Peter’s characteristics, linking him with the Pan I already talked about, is music.

Just like his eponym, he fabricates a pipe and by playing he enchants fairies and animals alike.

Even though Rackham sometimes slip and shows us other fairies playing instruments, often strings, I don’t believe there’s any mention of it and we’re left wondering whether Peter enchants them because of some supernatural power or just because they were holding balls with no music. Anyway, his playing is what grants him the wishes that get him flying again. The coloured plate above is probably one of the most famous illustrations in the book, often used as cover, but my favourite is its black and white version (below).

His enchanting of birds is shown in a black and white illustration, where we can see Solomon high on a tree, pretending to be indifferent and not really succeeding at it. Even if Peter got rid of his nightgown, his pose is still the one of a child.

Other illustrations

As far as I could understand, Arthur Rackham has been the only one to illustrate Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, if we do not take into consideration independent artists for just a minute. The most notable exception is probably All About Peter Pan, an adaptation of Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens written by Emma Gelders Sterne and illustrated by Thelma Gooch with 8 full-color plates in watercolor and several inkworks. In published in New York by Cupples & Leon, in 1924.

Other illustrated editions of Peter Pan mostly focus on the Peter Pan and Wendy story arc and I’m not fond of that. There are however some beautiful illustrations that are linked with the theme of music and Peter as the Piper of olds.

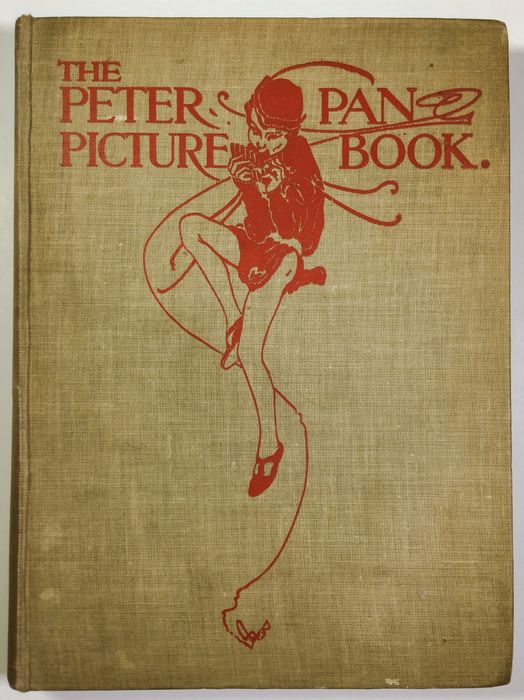

1907: The Peter Pan Picture Book

In 1907, Alice B. Woodward illustrated The Peter Pan Picture Book, published after the success of the play and following the publication of Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens. It featured 28 illustrations, alongside a simplified narration of the tale penned by Daniel O’Connor.

Woodward’s Peter Pan is fairly similar to the one we are used to think about, dashing and with fancy pants: you can find a spotlight and some illustrations here.

In the book, there are a couple of music scenes: the one above, where Peter plays for birds, and the ostrich scene (below).

We also see Peter sailing in a way that’s very similar to the way he sails on the Serpentine: in a bird’s nest, paddling, and using his coat as a sail.

Alice Woodward was one of the most prolific illustrators of the Golden Age and, alongside children’s books, she also did scientific illustrations. I already talked about her when I wrote about the many sources of inspiration for Disney’s Fantasia and specifically the Nutcracker fairies.

Her father was the Keeper of Geology at the Natural History Museum in London and she studied at the South Kensington School of Art, and later at the Westminster School of Art, before moving in Paris to attend the Académie Julian. She also studied privately with Joseph Pennell (an American mostly known for her anti-Semitic travel book The Jew at Home: Impressions of a Summer and Autumn Spent with Him which is absolutely appalling) and Maurice Greiffenhagen, who granted her a first commissions to illustrate children’s books for J.M. Dent and Macmillan and Company. She [also] illustrated Lewis Carroll‘s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

1907: The Peter Pan Alphabet

In the same year, another Peter Pan inspired book was published, this time with illustrations by Oliver Herford.

It too was produced following the play, and before the novel, and it was published by Charles Scriber’s Sons in New York.

As you might expect, it’s an A-B-C book, with double pages composed of verses on one side and illustrations on the other. It’s meant to teach children the alphabet, so you have A is for actress, B is for Boys, C is for Crocodile.

It’s not particularly good, but some of the pages are rather amusing, like X for X-Rays (the only way you can see Hook inside the crocodile at this point).

1921: Mabel Lucy Attwell

Mabel Lucy Attwell was a British illustrator and comics author, who worked on Mother Goose (1910), Alice in Wonderland (1911), Hans Christian Andersen‘s Fairy Tales (1914), and The Water Babies by Charles Kingsley (1915). She approached Peter Pan in 1921 for an abridged edition written by May Byron (1921), and of course we’re talking about the Peter Pan and Wendy story. You can find some pictures here, alongside an article in Italian. She too works on the scene of Peter sailing in a bird’s nest

1924: All About Peter Pan

This is one of the few adaptations and reworkings on Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens and it is retold for children by Emma Gelders Sterne, an Alabama-born writer and activist. She tells a small part of the story, featuring Peter in Solomon’s island, and with no fairies in it. Thelma Gooch is the illustrator and she gives us beautiful colour plates and black and white illustrations with a highly naturalistic attention. I give you all I could find.

In the front page illustration, we see Peter repairing the nest that will serve him as a boat to escape Serpentine Island and go back into the Gardens.

If you are not quite grown up

you will remember Solomon’s Island,

where all babies are birds

before they leave the Never-Never Land

to live with their mothers and daddies.

In the black and white illustration, we see Peter sitting on a branch, though the pose is more baby-like and less bird-like, if compared to Rackham’s take on the same subject.

Grown-ups cannot remember the beautiful island,

but they know that when they want a baby

they must ask Mr. Stork to fly to the Never-Never Land

and fetch them one from Solomon’s Island.

If you remember the particular for of American illustrator Paul Bransom on The Wind in the Willows, his realism reminds a lot of the approach chosen by Thelma Gooch for illustrations such as this Serpentine Island (called Solomon’s Island) or the following page’s birds.

So, once upon a time,

when Mr. Storm came flap-flap on to the island,

all the birds stopped their games

and fluttered about him.

The same black and white illustrations are sometimes used twice, as you can see with this standing Mr. Stork.

But Mr. Stork,

looking very important,

walked straight up to Solomon Caw,

where he sat on his great rock in the sunshine.

All the little birds said,

“Chirp, chirp”,

which means in bird language,

“I want to go”.

But Solomon Caw looked at them

and they were very quiet.

And when his mother saw Peter was gone

she cried and cried.

In this retelling, we see a point of view we don’t get to see in Barrie’s work: the one of Peter’s mother.

They did not know Peter at all,

and they laughed at him

because he was so different from a bird.

But Peter grew lonesome

because he could never go to the park

where children played all day long

and where even the little birdies can go

to look for crumbs and nice fat worms.

And he could hardly wait

for night time to come,

for Peter can only go to the park

when the real children are in bed.

Other notable stuff

Francis Donkin Bedford illustrated one edition in 1911, and gives us this beautiful scene of Peter sitting on a rock and enchanting Neverland animals by playing a double flute, much more similar to a Greek aulos than a Pan pipe in the traditional sense.

The flute is fairly similar to the one we see him playing in George Frampton‘s bronze statue, currently in Kensington Gardens. The statue was commissioned by Barrie himself and installed in the Gardens overnight, without announcements and without permission, and he wrote a note on The Times the following day, speaking about himself in third-person. You have to love this kind of nuts. It’s currently a Grade II* listed building and has been so since 1970.

“There is a surprise in store for the children who go to Kensington Gardens to feed the ducks in the Serpentine this morning. Down by the little bay on the south-western side of the tail of the Serpentine they will find a May-day gift by Mr J.M. Barrie, a figure of Peter Pan blowing his pipe on the stump of a tree, with fairies and mice and squirrels all around”

No Comments