Last week I continued down Arthur Rackham‘s trail and I started writing a bit about his work on the first version of Peter Pan, one I actually prefer a lot over the more well-known Neverland story: Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens. His illustrations are incredible (and they’re a lot): I started from birds, one of the main groups of characters of the story, and today I’ll get into fairies.

Fairies

Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens is the first work in which we make our acquaintances with tiny winged faeries and lots of the things we see in the much less appealing Neverland story arc make much more sense (and Tinkerbell might result in a slightly less appalling character). Faeries don’t like to be seen and this is how we meet them in the very first illustration: hiding.

The first illustration after the map, in fact, shows us a human, adult figure, and a bunch of faerie creatures hiding under the roots of a tree in both a playful and a frightened attitude. The human doesn’t appear in the final version of the text, but Rackham was also familiar with its first version, The Little White Bird, where we meet the character of Pilkington, a schoolmaster who leads his students through the Gardens and sends the faeries into hiding. According to Maria Tatar, this might be him.

The theme comes back times and times again, with a dedicated illustration once Peter is able to escape the Serpentine Island and come back in the Gardens.

The distance between fairies and children is stressed by this separation: children play in the gardens during daytime, fairies come out at dusk when the Gardens are closed. This makes Peter even more a in-between, a strange hybrid suspended between two worlds, so much more than Neverland’s Peter.

Regardless of this, Rackham takes a chance to show us what the faeries’ life might be like when they’re not on the surface a creates small domestic scenes under the roots of a tree: one fairy is tending to the fireplace, another group is sleeping in what seems to be a scene from an ancient Rome household, and at the door an ambulant rat is delivering goods. These scenes are absolutely enchanting and if you like these kind of things I suggest you check our both Jill Barklem‘s Brambly Hedge and Tony Wolf‘s Woodland Folk series (I absolutely adore both).

Their attitude is significantly different than the one we see them while they’re circling around the head of another, older and more amiable character: old Mr. Salford, who Rackham shows perusing the gardens next to Albert’s Memorial Monument (being therefore quite close to the Park’s border). Maybe there’s hope in senility and one might expect to go back to being more connected and more benevolently seen by fairies when he grows old.

“Old Mr. Salford was a crab-apple of an old gentleman who wandered all day in the Gardens.” (Plate 10)

The possibility of seeing them in daylight, however, is often hinted at, as it would be no fun strolling in the Garden without having at least a vague hope at catching a fairy and Barrie knows this very well. And encounters do happen: sometimes, fairies meet with humans and pretend to be flowers (lilies, bluebells, crocuses, hyacinths and such), and when the peril is gone they rush home to tell their mothers, just as much as children will, one might expect.

“But if you look, and they fear there is no time to hide, they stand quite still pretending to be flowers.” (Plate 26)

Anyway, exceptions aside, fairies usually come out at dusk. Their houses too are hidden because they are “the colour of the night,” and of course you can’t see night during the day, can you? Their palace, “built of many-coloured glasses,” is the “loveliest” of all royal residences.

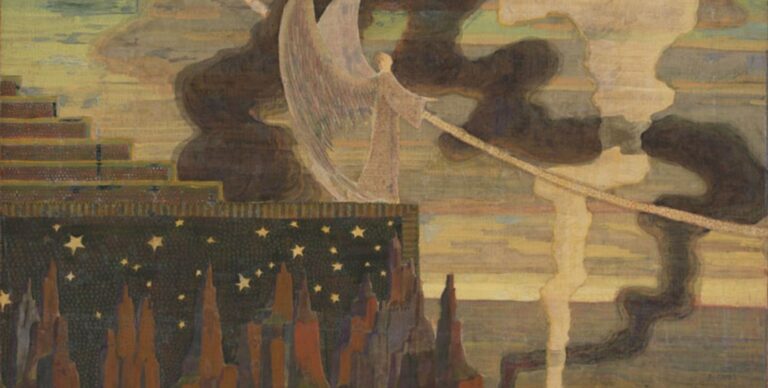

Their playfulness is an integral part of their behaviour, including dances. Though they’re sometimes shown in formal attire when it comes to the Court, their dances are more often a manifestation of play and Rackham gladfully picks up on that, as it happens in the plate below, where a fairy is shown dancing on a tightrope made by a spider’s string and using a spiderweb as a safety net, while another one is playing a miniatured cello.

Dancing is indeed an integral part of fairies’ mood, to the point where it’s synonymous with them being happy (and they don’t have a real word to say so).

Fairies forget all their steps, when they’re sad and, as we’ll see, this is bound to happen when we meet the loveless Duke of Christmas Daisies. The flowers and plants picked by Rackham in the illustration, though he’s deciding to show us a scene that doesn’t really happen, are meant to keep the link with the time and place of the tale: Holly for Christmas, Daisies for the sad Duke.

Fairies, as I was saying, are strongly connected not only with daylight and night time, but with seasons as well, an idea that artists at Walt Disney Studios will fully absorb when working on fairies for Fantasia (I talked about it here and here when I ran my series on the Nutcracker).

In one of the earlier plates, they are shown dancing and in full enjoyment of the season’s passing, in particular of fall. It’s one of the first seasons we meet with, and this influences a lot the gloomy atmosphere of the tale. As we’ll see, fairies have troubles of their own and they’re not quite as dancey as Rackham pictures them.

In fall, dead leaves are also used to sew curtains for the summer, and we see this in an “indoor” (or maybe should I see “underroots”) scene that has the high gloomy feeling of a lower-class London indoor scene with seamstresses working their fingers to the bone. The bare setting, with just a poor table and materials hanging from the ceiling, push this further and Barrie himself defined this illustration as «the grayest thing».

And where there’s fall, winter is soon to follow, but a snowy Kensington Gardens is the setting for most of Maimie Mannering’s adventure, so I’ll show you these illustrations in her setting.

Going back to fairies, sometimes they’re almost maternal, in their understanding that Peter is not a menace but simply a child. As such, they mix playfulness with sweetness with that gentle cruelty that pervades all characters and situations of the book.

“The Serpentine begins near here. It is a lovely lake, and there is a drowned forest at the bottom of it. If you peer over the edge you can see the trees all growing upside down, and they say that at night there are also drowned stars in it.” (Plate 7)

As far as I could understand, the above illustration was originally plate 7, and was re-worked in the 1912 edition with a close-up on fairies. The drowned stars are kept as part of the backdrop, but the close-up really helps us appreciate that, while the sky has a reflection in the water, the fairies do not, stressing their supernatural nature. Dragonflies and butterflies, albeit being a scene set at night, are here presented both for scale purposes and to underline the connection of fairies with the natural element, connection children have and adults lose over time.

They’re not completely benign, though, and in particular, we’ll soon learn that they don’t get along that much with birds, and this turns out to be a bit of a problem for Peter, at least while he’s still operating under the illusion of being one.

The problem is solved, on one hand, by the first fairy who hears Peter’s voice: he’ll be the one to point out that Peter is no bird at all, but a child, thus allowing a connection between him and the fairies, on one hand, and making impossible for him to fly again on the other. Peter loses the only truth he had, the conviction of being part-bird, and this completes his transition from something defined to an in-between, a creature trapped between multiple worlds. At first, however, he only scares fairies away.

Rackham decides to picture this fairy in a very different way from the others, focusing on the stamp she has been using to hide (which we see on the ground) and giving her clothing that’s clearly leftovers found in the Gardens. It’s more like a troll and totally dissimilar to the ethereal airy creatures we have seen so far. Rackham decides to integrate Barrie’s description of the faerie’s world with another layer of complexity as if there were two kinds of fairies, but this distinction in Barrie’s prose is of different nature.

If you remember from my dissertations around The Wind in the Willows, in particular my piece on the Wild Woods, there was a social subtext lots of critics have underlined and Disney didn’t fail to pick up: there’s upper-class, middle-class, and working-class, in those woods, and the working class is not at all friendly. The theme is not completely lost in Barrie’s fairy world, where we have a court, nobility, a chamberlain, and workers. We meet these workers at the very beginning, as one of the first encounters between Peter and the fairies, and they’re among the first to be scared away.

“A band of workmen, who were sawing down a toadstool, rushed away, leaving their tools behind them.” (Plate 14)

Their choice of clothing is very particular, with that strange embroidered beret and the towering fur one, that seem to suggest immigrant fairies, tools scattered all over, and a knotted bundle on the nearby branches. Overall, it’s a masterpiece of detailing and care.

The other “working class” fairies we meet are linkmen, defined as:

(ˈlɪŋkmən)

NOUN Word forms: plural -men

(formerly) a man who carried a torch for pedestrians in dark streets

Just as much as there’s lower class, we eventually get to meet the court, where Queen Mab resides, and the first figure Rackham chooses to illustrate is the Lord Chamberlain, in the act of performing one of his duties: telling the time. And he does so in the most professional way ever: he blows on a dandelion and counts the stems.

Then we meet the court and even in this scene Rackham decides to show us some social layering, with servants and rat-pages in the background.

Even in the formal circumstance of the ball, fairies behave like children and they’re unable to remain dignified for long: they soon start to “stick their fingers into butter” or to “crawl over the tablecloth chasing sugar”. There’s no tablecloth, in Rackham’s illustrations, and there are no attractive male fairies either, so you can’t really blame anyone for not being interested in such a thing as a ball.

At the centre of the court is Queen Mab, a name Barrie takes from Shakespeare, but not from whence we think. The Queen in A Midsummer Night’s Dream is Titania, as you should remember. Mab appears in Mercutio’s speech (Romeo and Juliet) and is far from being the queen: she’s the «fairies’ midwife» and she grants wishes.

“O, then, I see Queen Mab hath been with you.

She is the fairies’ midwife, and she comes

In shape no bigger than an agate-stone

On the fore-finger of an alderman,

Drawn with a team of little atomies

Athwart men’s noses as they lies asleep;

Her wagon-spokes made of long spinners’ legs,

The cover of the wings of grasshoppers,

The traces of the smallest spider’s web,

The collars of the moonshine’s wat’ry beams,

Her whip of cricket’s bone; the lash of film;

Her waggoner a small grey-coated gnat,

Not half so big as a round little worm

Pricked from the lazy finger of a maid:

Her chariot is an empty hazelnut

Made by the joiner squirrel or old grub,

Time out o’ mind the fairies’ coachmakers.

And in this state she gallops night by night

Through lovers’ brains, and then they dream of love;

O’er courtiers’ knees, that dream on court’sies straight,

O’er lawyers’ fingers, who straight dream on fees,

O’er ladies’ lips, who straight on kisses dream,

Which oft the angry Mab with blisters plagues,

Because their breaths with sweetmeats tainted are:

Sometime she gallops o’er a courtier’s nose,

And then dreams he of smelling out a suit;

And sometime comes she with a tithe-pig’s tail

Tickling a parson’s nose as a’ lies asleep,

Then dreams, he of another benefice:

Sometime she driveth o’er a soldier’s neck,

And then dreams he of cutting foreign throats,

Of breaches, ambuscadoes, Spanish blades,

Of healths five-fathom deep; and then anon

Drums in his ear, at which he starts and wakes,

And being thus frighted swears a prayer or two

And sleeps again. This is that very Mab

That plaits the manes of horses in the night,

And bakes the elflocks in foul sluttish hairs,

Which once untangled, much misfortune bodes:

This is the hag, when maids lie on their backs,

That presses them and learns them first to bear,

Making them women of good carriage:

This is she—”

(Romeo and Juliet, Act I – Scene IV)

The wishing-granting part is kept, in Barrie’s tale: as we have seen, she grants Peter a wish, and he decides to split that in two.

Mab also appears in Joshua Poole‘s 1657 work, called The English Parnassus, or, A helpe to English poesie containing a collection of all rhyming monosyllables, the choicest epithets, and phrases : with some general forms upon all occasions, subjects, and theams, alphabeticaly digested (yeah, I know). In this work, she appears as the Queen of Fairies and, this time, she’s Oberon’s consort. I do not want to know what happened to Titania.

Percy Bysshe Shelley entitled to Mab his first large poetic work: Queen Mab: A Philosophical Poem (1813) was later revised and republished as The Daemon of the World (1816) and it takes about revolution, ever-changing nature, human virtue and society.

In 1814, Henry Fuseli portrayed Queen Mab as a dream fairy queen in one of his paintings featuring dormant people and unsettling circumstances. So did Turner in 1846, giving us a Queen Mab’s Cave.

“Queen Mab” is also a chapter in Herman Melville‘s Moby-Dick (1851), where se see a dream of one of the sailors.

Rackham shows us Queen Mab in an unusually slender illustration, sheltering herself with a dandelion and her flowering gown being held by two pages.

In 1920, The Book of Fairy Poetry by Dora Owen featured a piece called “Queen Mab” by Ben Johnson and, since the book was illustrated by Warwick Goble, we get to see his take on the faerie character.

In contemporary fiction, it’s worth mentioning that Queen Mab is ‘The Queen of Air and Darkness’ In Jim Butcher‘s Dresden Files, and she lives with her Winter Court in a dark icy castle in Nevernever: she’s cold, and her thing is deals and unbreakable pacts, like a proper King of Hell. She’s also a recurring supporting character in the Hellboy comic book series, and goes by the name of Mrs. Mabb in Susanna Clarke‘s wonderful Ladies of Grace Adieu. She also appears in Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, with her court, and [spoiler alert] she’s the Queen of Hearts in Andrzej Sapkowski‘s retelling of Alice in Wonderland.

Upper of lower-class, anyway, the mischievous character of fairies emerges in different circumstances. Malicious fairies are portrayed by Rackham in a far more goblin-like way than regular fairies.

One of the situations in which their bad sides show, is when they’re playing tricks with the board to make sure people will be out of their way, for instance, when they’re holding their balls and banquets.

But what do fairies eat and where do they take food from? Barrie has this detail covered and Rackham soon follows. Butter is a special kind of vegetable butter (nothing to do with bog butter, which is far from being vegetable and I learned some disgusting thing by visiting the Iron Age Bog Bodies Exhibition in Dublin, a few years ago).

The tree, of course, is Rackham’s piece of cake, spooky and gnarled and menacing, but fairies do not seem to be bothered by it: the scene set in its trees is cosy and domestic, with three generations of fairies gathered around the recipe of what one can assume is a cake, small eggs in a basket (uncaring of scale, but I guess now we know why birds and fairies do not get along, do we?) and an assistant cutting the butter in the background.

There’s also nectar, in a fairy’s diet, and wallflower juice is particularly good to revive dancers after dancing too much, especially during the frenzy cause by Peter’s pipes (but more on that later). Now, of course wallflower is a kind of herb, Erysimum, which comes in a whole set of different colours, but it’s also a way of indicating someone who doesn’t participate in dancing or interacting at a party. According to the On-line Etymology Dictionary, the «colloquial sense of “woman who sits by the wall at parties, often for want of a partner” is first recorded [in] 1820», way before Barrie’s work. Knowing him, it’s highly possible there’s some satire in this.

Incidentally, we should also note that this is probably the only illustration in which we have a male fairy that’s not completely hideous.

I do believe in fairies!

The Duke of Christmas Daisies

Strongly connected with faeries is the character of the Duke of Christmas Daisies, a fairy coming from far away and cursed with the inability of falling in love. While I’m not so sure that Christmas Daisy are a thing, the Victorian Age was certainly enamoured with daisies and they’re a recurring theme in Christmas cards, even if they’re far from being particularly in topic, if you want my opinion. The Duke himself is also the character of a fairy play by one Maysie/Maisie Edmondston, but I was literally able to find only a couple of references to this (here, here and here). According to some very unreliable sources, it was indeed adapted from Barrie’s The Little White Bird.

Anyway, Rackham gives us an illustration of the Duke and decides to give him the orientalist looks than his description, but also plays a trick by giving him some of Barrie’s characteristics and putting some of himself into the doctor examining his loveless heart. There’s a pun, there, something we’ll probably never get.

Christmas Daisies are all over his robe, but the turban on his head really brings us to Edmund Dulac‘s illustrations, always full of orientalist traits even when it was out of place, whom Rackham knew and loved. If you remember, the prince in his Little Mermaid was wearing a similar headgear (we have seen it a couple of weeks ago), and so does his Bluebeard.

Queen Mab is confident that one of her fairies will be able to warm the Duke’s heart, and this someone is a fairy called Brownie. Rackham shows her wingless, almost ladylike, under the winter berries and with a gown that spells snow. This is one of the most beautiful illustrations he ever did, in my opinion. The sad fairy, who’s not dancing as we have seen before, has lost her wings but not her grace.

When indeed the Duke experiences the strange and new feeling of being in love, it’s of course his trusty physician to diagnose him and he informs him as a gentleman should. This of course brings back joy, and dance, and incidentally other enthusiastic marriages, to Queen Mab’s Court.

‘My Lord Duke,’ said the physician elatedly, ‘I have the honor to inform your excellency that your grace is in love.’ ” (Plate 47)

Queen Mab’s court in the background is clearly distinguished, in their French and British attires, and there’s even one dressed as a judge, but the page holding the crown comes clearly from the same place the Duke comes. Wherever that is.

It’s worth mentioning that, among all the Royal weddings, the Lord Chamberlain is finally rewarder of all his troubles and marries the Queen.

No Comments