Between the Chinese and the Arab Dance, both the Nutcracker Suite and Fantasia place another dance, the Dance of the Flutes or Dance of the Reed Flutes. Let us go back to them, though, and then all we’re missing is the Russian Dance and the Waltz of the Flowers.

3. The Nutcracker Piece by Piece (3)

Flowers are falling on a stretch of water and they turn into ballerinas, in this lovely but not particularly popular piece.

3.3. Dance of the Reed Flutes: the music

Also called Danse des Mirlitons or Dance with Little Fifes, the musical number features Danish shepherdesses playing what is also referred to as Eunuch Flute, a woodwind musical instrument in use between the XVI and the XVII Century and consisting of a wooden tube with the end closed with a thin membrane, like the vellum of a drum. It is closer to a kazoo than to a flute and it was firstly mentioned by Marin Mersennus. Irish writer Samuel Beckett wrote a series of fifty-nine small poems in French called Mirlitonnades.

There’s a huge confusion about it, because in Italian the piece is called “Pastoral” whereas the subsequent piece, Mother Ginger and the Polichinelles, is referred to as “dance of the zufoli” (picco pipes) and sometimes the dance of the shepherdesses are referred to as “marzipan”, which is the ginger bread of the following piece and now I’m super confused.

One of the reasons you might be confused about, is that we’re coming from tea and coffee and chocolate, we’re in the Land of Sweets, and we have Danish girls with flutes. I found a wonderful explanation of the meaning of this, on this website. Apparently…

Mirliton du Pont-Audemer is a French pastry that is rolled into a tube, filled with chocolate praline mousse, and dipped in chocolate, not unlike Cigarettes Russes cookies… or the mirliton flute.

Interestingly, there are other kinds of mirlitons, too.

Mirlitons de Rouen are almond-topped puff pastries, tarts, or cakes. Maybe all this almond and praline business is how we’ve made the leap to marzipan, which is an almond paste that can be formed into just about anything and is also a popular Christmastime treat.

It’s a beautiful article and I suggest you check it out also for explanations on other pieces from The Nutcracker.

In this piece, the double meaning bridges sweets and flutes together, and of course it makes sense that the people playing flutes would be shepherds, because of the whole Pan/pastoral imaginary.

Ivan Vsevolozhsky‘s original costume sketch for The Nutcracker (1892) featuring one of the Danish shepherdesses.

There’s a Dance of Mirlitons also in La cigale et la fourmi, a XIX Century three-act opéra comique by Edmond Audran, loosely based on Jean de La Fontaine‘s version of Aesop’s fable The Ant and the Grasshopper and worded by Henri Chivot and Alfred Duru. As it happens in a Disney version of the same tale, the story has a happy ending, at least for the Grasshopper: the “ant” (a working man) looks after his friend the “grasshopper” (the vain man). The instrument accompany a chorus in Act II – Les mirlitons, les crécelles – with reed flutes and rattles as instruments.

Madonna sampled the melody of this piece for her song Dark Ballet, featured in Madame X (2019).

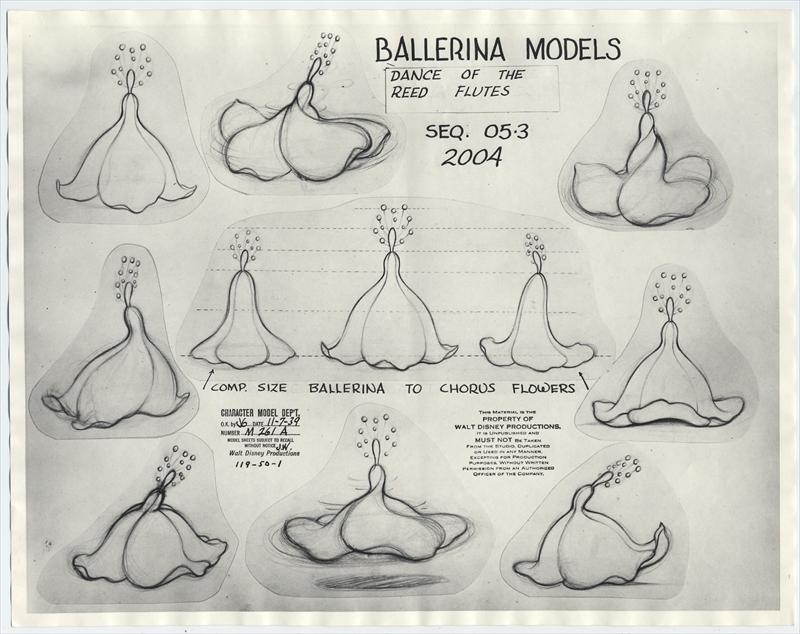

3.3. Dance of the Reed Flutes: flower ballerinas

The first concept for having dancing flowers was probably developed as early as 1935 by Ferdinand Horvath and Bianca Majolie for a piece that was originally called Ballet des Fleurs, Flower Ballet. I already talked about Bianca in the fairies segment: she was an incredible Italian-born artist and the first woman to become a storyboard artist for Walt Disney. Ferdinand Horvath has also already featured on these pages and you can read more about him here: he was a highly versatile Hungarian immigrant, a book illustrator and artist who also worked on pop-up books and three-dimensional models (including a windmill for the amazing segment The Old Mill, my favourite Silly Symphony of all times). John Canemaker dedicates a whole chapter to him in his Before the Animation Begins: The Art and Lives of Disney’s Inspirational Sketch Artists (Hyperion Press, November 1996), reference text for anyone who wants to know more about the artists that made these cartoons possible. They also both have dedicated chapters in the first volume of the They Drew as They Pleased series.

According to the same book, another artist who worked on the abandoned project was Gustaf Tenggren, a Swedish-American illustrator who had also worked on some Norse fairy-tales (yeah, it’s all coming together) collected in Among Gnomes and Trolls (following illustrator John Bauer). He also illustrated The Ring of the Nibelung, The Night Before Christmas by Clement C. Moore and Thumbelina by Hans Christian Andersen.

You can read a little more about this abandoned project here.

The artists depicted here the same impressionistic technique that’s characteristic of all the dances, except for the opening with the fairies: the characters are painted in bright colours, in contrast with the dark background.

“I like the coloured light coming out of the darkness: it is a little like Rembrandt’s painting, where he swished his highlights out from a black background”.

Stokovski (January, 23rd 1939)

The the abandoned Flower Ballet and the sketches developed by Horvath and Majolie back in the days would also serve as an inspiration for animation icon Mary Blair in working for the Carnival of the Flowers in The Three Caballeros. She had started as an as an animator with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and was one of the most important artists at Disney Animation from 1940 to 1968: she also worked on concept sketches Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan, Song of the South and Cinderella.

Eventually, the ballet turned into a classical ballet in the more traditional sense, with flowers basically performing turns and a circular dance like classical ballerinas as typically seen in figures like the pirouette (whirl) and the fouetté. The group whirling has also a Turkish form of dynamic meditation (see here).

The final result is flowers gently falling on water and, with a graceful twirl, turning into ballerinas with elaborate headpieces, with a white prima ballerina playing the lead role.

Just as it happened for the Arabian Dance, real-life dancer Marjorie Belcher was brought on site in order to provide references for the dancers. Few years before, aged only 14, she had already been the double of Snow White (1937). She will also model for Hyacinth Hippo in the Dance of the Hours and, later on, as the Blue Fairy in Pinocchio (1940). The pirouettes were particularly tricky to match with the music, a task undertaken by Louisa Field, who was Stokovski’s Assistant Music Cutter.

An original sketch for this sequence can also be seen at the MOMA (here).

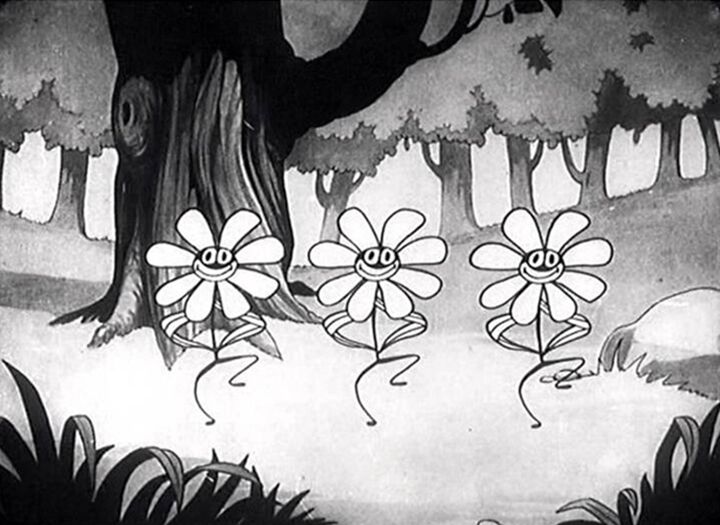

This, however, hadn’t been the first time in which we see flowers dancing, at least in a Disney segment: the first has to be the Silly Symphony Springtime (1929) defined by the Studio itself as, “The first animated picture in which flowers were used to interpret a ballet.” It also has a connection with Fantasia, and particularly with the Pastoral Sequence, because it’s one of the first cartoon representations of a thunderstorm, but in the first pieces we see daisies performing a merry dance. As it often happens, daisies are caricaturized as blackfaces, the highly racist theatrical make-up used in the United States throughout the XIX and XX Century, and with which Disney’s early cartoons seems to be obsessed: oddly enough, it does seem to be a late addition, as daisies are pretty much always portrayed as regular smiling daisies in the concept sketches. The girl tree was animated by Les Clark and there are beautiful coloured sketches in the book Animation from the Archive series (although it’s a shame that those pictures have no text whatsoever).

In One Hundred and One Dalmatians, this is the short aired on television while the puppies are at Cruella’s Manor.

Dancing flowers also feature in the other “seasonal” Silly Symphonies that followed in 1930, although not so much as in Springtime. They also come back in Playful Pan (also 1930), in which the faun-like God dances around and plays using flowers as instruments, but we have to wait for Flowers and Trees (1932), the first Technicolor cartoon, in order to see again a chorus of dancing daisies picking up their roots and sprouting little feet. The main characters, though, are a dashing young male tree and a nasty looking hollow tree, who battle for the graces of a slender female tree.

Similar dancing flowers also feature in another highly confusing Silly Symphony from 1934, The Goddess of Spring, an apparent attempt to bring to the screen the myth of Hades and Persephone, except the God of the Underworld is depicted as a Mephistopheles who tries to bribe the wife with huge diamonds and there’s no Demeter in sight. There’s people speaking and singing, in this segment, and particularly Persephone is voiced by American singers Jessica Dragonette and one Diana Gaylen. Music was composed by Leigh Harline, mostly known for When You Wish Upon a Star. The Goddess herself bears a high resemblance with Pinocchio’s fairy.

Interestingly enough, in this cartoon the daisies loose their racists features (at last) and they perform a dance that will remind us of the Russian Dance in Fantasia.

Similar concepts will also be explored with the flowers for Alice in Wonderland, although those are firmly rooted down and that’s pretty much how Alice is able to escape once they get upset. Doris Lloyd will be voicing the lead rose, Queenie Leonard is her baby blossom, Lucille Bliss is both the sunflower and the silly tulip, Marni Nixon is a bunch of singing flowers and Norma Zimmer has a grand entrance as the white rose.

Years later, Eyvind Earle seemed to be thinking about dancing flowers for a sequence in Sleeping Beauty, in one of his incredible concept artworks (if you’re not familiar with him, make sure that you are, like now). The work I’m thinking about is not available on-line and you can find it the Design book of The Archives series, but I’ll leave you with something else instead.

3.3. Dancing Flowers: is that a thing?

That’s certainly a thing. It must be because of the delicate movements, it might be because of the costume they wear, designed to highlight such movements, that often resembles petals, but the idea of female dancers as flowers is as frequent as the one of dancers as birds. Tchaikovsky himself in The Sleeping Beauty gives us the Fée des lilas, the Lilac Fairy as a flowery character (see this concept design by Léon Bakst in 1921).

There’s also a fair variety of ballets in which the dancers are literally flowers: in Act II of The Talisman by Riccardo Drigo, choreographed by the same Marius Petipa who also did The Nutcracker and The Sleeping Beauty, the main character Niriti, daughter of the Queen of the Heaven, appears as the Goddess of the Flowers in the gardens of King Akdar’s palace and dances with her subjects; in Tableau 2 of The Seasons by Alexander Glazunov, also choreographed by Marius Petipa, flower fairies dance with Zephyr and one of the main characters is a rose; in Le Réveil de Flore, also by Riccardo Drigo and still with Marius Petipa, the main character is Flora, the Goddess of the Spring. If you want to look at it the other way around, however, the Prima Ballerina is also a variety of rose.

Russian photographer Yulia Artemyeva did a beautiful series of pictures comparing ballerinas and flowers: you can see some of them here, alongside an interview.

3.3. The specific flowers

The flowers depicted in the segment seem to be peach blossoms, which have a rather characteristic way of falling in clouds and present the defined inside that will turn into the headdress for the dancers on water.

They are probably the most important flower ever in several oriental cultures. In the opening chapter of the Chinese novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, a 14th-century historical novel attributed to Luo Guanzhong, the three main characters Liu Bei, Guan Yu, and Zhang Fei take their oath of brotherhood under a blooming peach tree. The Peach Blossom Spring is a fable by Tao Yuanming about the discovery of an utopian world by a fisherman who sails through a river into a world of blossoming peach trees.

The expression shìwaì taóyuán (Chinese: 世外桃源 “the Peach Spring beyond this world”) has become a popular four-character idiom (chengyu), meaning an unexpectedly fantastic place off the beaten path, usually an unspoiled wilderness of great beauty.

The Peach-blossom Spring, painted by Ding Yunpeng, 1582

No Comments