Edit: for some reason, this article became quite popular.

The comment section is closed, but you should read this: it’s a comment from a Chinese-American reader, drawing the attention to the cultural controversy surrounding this particular piece, which is still staged in a very harmful way.

An addictional section on the article summarizes my answer you also find below in the provided link. ♡

As I told you, this is a special night, a night of stories. My grand-grand mother used to weave with her friends, in nights like these, and they told each other stories. I am not a particularly skilled weaver, but stories is something I do well. I started digging into Walt Disney’s Fantasia and a hour ago I posted something on The Nutcracker and the flower fairies of the first piece. Let us see what happens next.

3. The Nutcracker Piece by Piece (2)

At the end of the Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy, the fairies collide mid-air and explode (gruesome, I know): their fairy dust falls on some mushrooms and they come to life to enact one of the most beloved sequences in the whole movie, the Chinese Dance.

3.2. Chinese Dance: the music

The Chinese Dance is one of the celebrations in honour of Clara and the Prince after they return to the Land of Sweets: just as it happened in The Sleeping Beauty ballet, the two main characters are visited by people from different Countries, bearing gifts, and if the Sleeping Beauty widens its horizons by having characters of other fairy-tales to come to visit, in this case the broadening is more literal and more geographical. The Chinese dancers arrive bringing tea.

There have of course been controversy and accusation of racism, both on the composer and on how the act was brought to the scenes in the different versions (see the Australian incident mentioned below the picture). I honestly find it less racist than the centaurettes only matching with centaurs of the same colour in The Pastoral Symphony, so I‘ll skip on that. What I find interesting is that The Nutcracker is not the only ballet with a random Chinese Dance. I suggest you read here, if you want to ready an accurate deconstruction of musical devices used to evoke orientalism and chinoiserie, from Giacomo Puccini’s Turandot to Albert William Ketèlbey‘s In a Chinese Temple Garden, from Sir Edwin Arnold‘s The Light of Asia to my personal favourite, Maurice Ravel‘s impression of the China cup in L’Enfant et les Sortilèges (1925), which incidentally also features the celesta, that bell-piano used by Tchaikovsky for the Sugar Plum Fairy. There’s also this essay you might want to check out, in which Angela Kang explores chinoiserie tendencies in Claude Debussy, Manuel De Falla, and Albert Roussel (early XX Century), alongside Gustav Mahler, the already mentioned Puccini, and of course Stravinsky.

There’s a Chinese Dance in Henry Purcell‘s The Fairy-Queen, one of my favourite, specifically in the final masque, again as a homage to the newly wedded couple: it is said to be a homage to Queen Mary’s famous collection of china porcelain and it features arias like “Thus, the gloomy world”, “Thus happy and free” and “Yes, Xansi”, sang by a countertenor in duet with a soprano.

3.2. Chinese Dance: animated mushrooms

If Bianca Majolie, Sylvia Holland and Ethel Kulsar were the geniuses behind the delicate sequence of the Sugarplum Fairy, the mushrooms were fathered by John Walbridge, one of the most hectic artists of Walt Disney studios.

He had done previously designed the short Mickey Mouse cartoon Thru the Mirror (1936), in which Mickey Mouse falls asleep after reading Through the Looking-Glass by Lewis Carroll, and dreams of transitioning in an alternate reality featuring a nutcracker, the King and Queen of Hearts, a dancing telephone and dancing gloves. The scene of the dancing gloves is so iconic that it receives a tribute in Aladdin, when the genie dances with the two giant projections of his own hands.

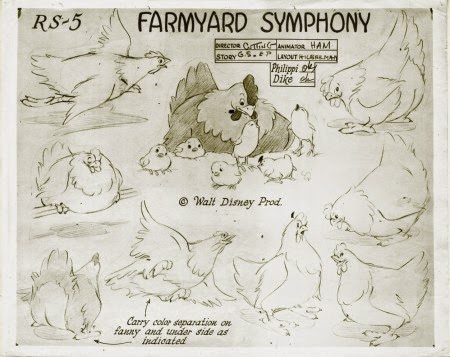

Despite being mentioned as a prospect to work on Snow White, he carried out working on shorts: for the Silly Symphony Woodland Café ( 1937), he worked on members of the insect orchestra; for the extravagant Wynken, Blynken & Nod (1938), which put to the screen the bed-time poem by Eugene Field about three children sailing and fishing among the stars in a wooden shoe, he did layouts; for Farmyard Symphony (1938), he did character design for some of the farm animals. The last short, although not particularly interesting plot wise, has an interesting and refined use of music and features two movements from from Beethoven‘s “Pastoral”, William Tell Overture, the overture to Semiramide and the overture from The Barber of Seville by Gioacchino Rossini, a piece from from Songs Without Words and a movement from Symphony No. 4 “Italian by Felix Mendelssohn, La donna è mobile from Rigoletto which then turns into “Sempre libera” from Act 1 of La traviata, both by Giuseppe Verdi, Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 by Franz Liszt. All squeezed into a 8 minutes short. Along with The Old Mill, it is considered one of the masterpieces preluding to wonders like Fantasia.

As soon as Walbridge started working on Fantasia, he moved to characters for the Russian Dance, the Dance of the Reed Flutes and, most importantly, the Chinese Dance.

If you take a look at the character sheet and earlier concept art, the first idea for the Chinese Dance had probably been less neat and more varied.

Flower girls made their appearances in the original concept, alongside a frog whose association with China in the animator’s minds was evidently an obvious picture. They are associated with good fortune in business, because of the healing spirit Ch’ing-Wa Sheng, and therefore often found in shops: although the animating team could take pride in having at least two Chinese-Americans in their staff, it is most likely that a lot of their direct experience came from visiting traditional districts like San Francisco’s Chinatown, the oldest enclave in North America and the largest outside of Asia, or one of the other three Chinese enclaves within the city.

Progressively, the scene became more clear.

But even when the concept sketches start featuring mushrooms, it is the contribution of choreographer Jules Engel that brought us the number we know now, with a sharp abstract contrast between the figures and the background.

The technique was also very peculiar, according to The Archives:

A special airbrush paint application on the cels of the mushrooms preserved the original pastel character of the sketches, and the special effect for dewdrops elevated the red and yellow caps to magical heights.

In the final concept, the small mushroom is only one, called Hap Low, continuing with a Disney tradition that indirectly kept quoting the ugly duckling and resonated with small children everywhere.

Disney had previously dabbled in chinoiserie with the black and white Silly Symphony The China Plate, in 1931, in which the décor of a china plate comes to life and tells the story of two star-crossed lovers, antagonized by an evil mandarin. It was directed by Wilfred Jackson, who will also direct A Night on Bald Mountain in Fantasia, and music was composed by Frank Churchill, who also will write songs for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Chinoiserie is not a theme anymore in a similar Silly Symphony from 1934, this time in colour, called The China Shop.

3.2. Chinese Dance: those dancing mushrooms

Just as we did for the Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy, one of my favourite things to do is try and look for references, so in this instance we might be wondering whether the idea of animating mushrooms and give them an anthropomorphic feature was an original idea of if there might have been some suggestion from previous artists.

The first story we find, is The Princess in the Forest (1909) and In the butterfly kingdom (1916) by Sibylle von Olfers, a German art teacher and a nun, daughter of a natural scientist and niece of German writer, illustrator and salonnière Marie von Olfers. In her work, initially solely intended for the amusement of her sister and family, a princess is living in a forest (you don’t say?) and gets help from dew children, moss children, toadstool and mushroom children. You can read a summary here. More than anthropomorphic characters, her mushrooms are half-human, but her style is delightful.

The same concept was explored by Swedish author and illustrator Elsa Beskow, who also did illustrations to her own children tale. She’s not widely known nor published outside of Sweden, but she’s probably the most important picture book creators for children’s book in the XIX Century. She started her work as a Christmas illustrator for the magazine Svensk Lärartidnings Förlag, which had a Christmas magazine run by Amanda Hammarlund. Her first publication, released in 1897, were illustrations to a nursery rhyme she knew from her childhood, Sagan om den lilla, lilla gumman, and made her breakthrough in 1901 with the illustrated nursery rhyme Puttes äventyr i blåbärsskogen, which became a classic. According to this website:

It’s the story of how little Putte wants to give his mother a present on her nameday and seeks the help of Blåbärskungen (the bilberry king) and his tiny assistants in filling baskets with lingonberries and bilberries.

She gives us some mushroom children in Children of the Forest (1910), a short tale about creatures who live under the roots of an old pine tree and their adventures throughout the seasons. Interestingly enough, also Sibylle von Olfers worked on a story where children were living under the roots of a tree: this must be a thing.

All these stories a little reminiscent of Barrie’s Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens: they’re children living pretty much by themselves in a fairy-world.

If we want to see some families, we have to turn to Edward Okuń, a Polish Art Nouveau painter who did paintings and illustrations including works for the manifesto magazine Jugend. Alongside some biblical works and lots of sceneries from his many travels, he also worked on mythical concepts like The Golden Yarn, Spring this Knight and Mermaid, and Driada. The work I had in mind when I brought him up was this Mother Mushroom with her children, painted around 1906. The poor thing looks positively miserable and I don’t want to say that it’s because the artist is Polish, though I confess that the thought had crossed my mind. The title underneath the illustration reads “Wo Die Buchen Dämmern”, Where The Beeches Dawn, and the illustration appeared on Jugen #45, at least according to this Tumblir.

There’s also a whole series of children illustrators who also dabbled in scientific or realistic illustrations of mushrooms and the most famous of them all just has to be Beatrix Potter. The famous and beloved author of Peter Rabbit developed a huge amount of watercolours of flora and fauna, some of them you have collected in a wonderful volume called The Art of Beatrix Potter. Her work as a naturalist, especially on mushrooms, led her to be widely respected in the weird world of mycology, although this was before she started publishing stuff about rabbits in wintercoats. She wasn’t allowed to publish any of her work, because of her sex and because she didn’t go to University (again, because of her sex),but a collection of her paintings is preserved at the Perth Museum and Art Gallery in Scotland, to whom it was donated by Charles McIntosh. Her work was published posthumously in 1967, when mycologist W.P. Findlay included her drawings in his Wayside & Woodland Fungi, fulfilling her desire to be published as a naturalist. In 1997, the Linnean Society issued a posthumous apology. It took them a while.

Her naturalistic attention and knowledge was of course not lost when she started drawing Peter Rabbit. Take a look at the beautiful depictions of the countryside in her The Tale of Johnny Town-Mouse, the ones of the pond in The Tale of Mr. Jeremy Fisher, the flowers in The Tale of Tom Kitten, and pretty much everything in Timmy Tiptoes. You can also take a look at her work in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum.

It’s also worth mentioning another Swedish illustrator, Signe Aspelin (1881-1961), which I didn’t know and I have to thank this blog for letting me discover her (the blog is excellent in general and I whish I had discovered it sooner, through my writing on Norse folk tales). She illustrated a book called The Rhyming Mushroom Book for Children (Småttingarnas svampbok. Bilder med rim), in which you have illustrations of mushrooms, rhymes and fairy characters like the King of Portobello Mushrooms (you can see it here).

If you’re looking for something unsettling, I also suggest you check out Der Giftpilz, I highly disturbing children’s book published by Julius Streicher in Nazi Germany in 1938. The “text” is by Ernst Hiemer, with illustrations by Philipp Rupprecht, and it uses the mushrooms as a metaphor to express how difficult it is to tell a Jew apart from everybody else, and the book is meant to be an “educational” text for German children. It was used in German schools and one copy is held at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

3.2. And what about mushrooms in fairy tales?

There’s a direct connection between mushrooms and fairies in folklore, because of the way mushrooms are sometimes organized into a circle: that thing is called fairy ring, ronds de sorcières (“witches’ circles”) in French, and Hexenringe (“witches’ rings”) in German, but the Middle English term elferingewort (“elf-ring”), meaning “a ring of daisies caused by elves’ dancing” apparently dates to the 12th century and Olaus Magnus reinforces the concept in his History of the Goths (1628), by saying that the rings are burned into the ground by elves dancing. British folklorist Thomas Keightley, around 1850, stresses that in Scandinavia during early XIX Century the belief persisted: the elfdans were seen as portals, zones in which mortals could see elves but elves were also able to catch them in the grip of their illusions.

And in their courses make that round

In meadows and in marshes found,

Of them so called the Fairy Ground,

Of which they have the keeping.

Michael Drayton – Nymphidia: The Court of Fairy (1627)

In these situations, what you’re seeing as mushrooms it’s either fairies or actual mushrooms which sprang from where their feet have danced.

In the last situation, it’s not very different from what we see in Fantasia, where the fairies are animating the mushrooms with the fairy dust resulting from their collision.

Addendum: racist stereotypes

After I closed the comment section because of the poisonous exchange you can still read below, a kind reader reached out to me commenting one of the main pages and invited me to address the matter of how this piece is fundamentally enforcing harmful racial stereotypes. I invite you to read their comment here: they’re 100% right and I 100% agree with them, especially in the matter that “everything is politics”. It is. You can read my answer right below.

In the original post, I intentionally skipped this aspect and I only briefly referred to it in the opening section, but I couldn’t pass up on such a kindly put request.

For your best convenience, I post here the same selection of articles I posted in the comment, so that those unfamiliar with the issue can look it up.

– “As ‘Nutcracker’ Returns, Companies Rethink Depictions of Asians”, published on the New York Times in November 2021 here;

– “Toning Down Asian Stereotypes to Make ‘The Nutcracker’ Fit the Times”, still by the New York Times but published in 2018 (note how the tone changes) is available here;

– “Sorry, ‘The Nutcracker’ Is Racist” published on The New Republic in 2014 is here;

– “Op-Ed: ‘Yellowface’ in ‘The Nutcracker’ isn’t a benign ballet tradition, it’s racist stereotyping” published on The Los Angeles Times in 2018 is here.

The Dance Magazine has a beautiful 2019 article by Phil Chan And Georgina Pazcoguin titled “A Fresh Cup of Tea: How to Make Nutcracker More Inclusive”, with some ideas on the matter, and you can read it here.

Here’s what I think, as I wrote in the comment: I think the problem lies in both the original music piece, filled with the exoticism and quirks in vogue at the time, the way Disney decided to implement that, and the contemporary depictions.

I think the music falls short as the so-called Orientalists painters did: it depicts something exotic for the sake of the exotic, with a vague allusion to what the author thinks the flavour of the culture is, but without any consultancy from actual people involved and without a real study into the musical culture of the countries involved.

It’s true, even if it doesn’t make it right, that the ballet features *sweets* and not people, and if Tchaikovsky is mocking other cultures, he’s also mocking his own, since there’s a Russian Dance between the Chinese dance and the Danish one. Still, the so-called Russian Dance is “Trepak”, which is a traditional dance, while all the other dances are made-up and flavoured pieces.

One usually says that “it was a different time”. Was it, though? The Nutcracker was performed in 1892, and all it takes is brief research to find out that Russia and China were in a splendid relationship, back then, and a person like Tchaikovsky could have easily reached for Chinese musicians if he really wanted to get it right. He didn’t. He didn’t recognise the need to.

Disney has even fewer excuses. The Studio could have done what the ballet is originally depicting, and put sweets on the screen: what we call the Chinese Dance is, in fact, the Tea Dance, the Arabian Dance is the Coffee Dance, and the Spanish Dance is the Chocholate Dance. They decided to do otherwise and enforce the stereotype, and I have no sources on whether the conversation even occurred.

I can only imagine how people like Wah Ming Chang might have felt and what they might have gone through in terms of bullying while working on the same production.

(for those who are not familiar with Wah Ming Chang, he was a Chinese-American designer, sculptor, and artist working at Disney, and he designed the snowflake fairies: I talked about him here.

Regarding contemporary depictions, it really is beyond me: why can’t we break free from the “Chinese” part and simply stick to the “Tea” part? Do they want something funny and light? Yes, they can use the very same music to mock the British and their obsession with tea. Why isn’t anyone thinking of that?

Or, I repeat, we could just stick with the teacups.

4 Comments

Stephen Rabin

Posted at 13:58h, 14 MayOne serious cvorrection. The Disney animator who did the Mushroom Dance was Art Babbitt, who did a number of works for Disney including the Wicked Queen in Snow White

shelidon

Posted at 08:05h, 18 MayHi Stephen, glad to see you here. I have re-read my article and I don’t believe I wrote anything about the animation if not a mention of Milton Quon that could be misinterpreted (I should have specified he worked on the Waltz of Flowers instead). I heartfully thank you for the integration. I don’t see where it’s a correction, but maybe you have spotted something I did not intend and I’ll be happy to correct it if you point it out.

Laurel Lee James

Posted at 17:38h, 16 January“3.2. Chinese Dance: animated mushrooms“ …with your clear reference to the animation, not design, of the mushrooms, the failure to mention Art Babbitt, animator of the mushrooms, is an epic fail. No matter who designed them, Art Babbitt gave them a life on screen; animation held in awe by animators to this day. He also bestowed the same legendary status to the Queen in Snow White, Gipetto in Pinocchio, the Thistles in Fantasia, the development and animated life of Goofy, an Academy Award for Country Cousin, etc.; as well as being a workers rights champion in the industry. Your dismissive handling of Stephen’s critique pointing out the egregious deletion of Art Babbitt from any of his work highlights how deeply uninformed you are. Either give Art Babbitt his due credit or make it very clear this is not an article about animation but about design only. Without exaggeration Art Babbitt is considered to be one, if not the greatest animator of the early Disney era. Another being Vladimir Tytla. His work speaks for itself. The designer of the mushrooms was very lucky to have Art Babbitt to be the one animating them, giving them their legendary status.

shelidon

Posted at 13:09h, 17 JanuaryLaurel, the tone of your comment is disgraceful and the way you’re harassing me on Instagram (multiple times, now) is frankly beyond ridiculous. I know who Babitsky was and frankly the only thing I would be interested in writing about is the Disney strike: everything else is out of my area of interest and beyond my expertise. The article doesn’t mention lots of other people who contributed in creating the piece, none of the animators and none of the musicians, for instance: should I expect equally harassing comments from the heirs of Stokowski? I would understand the content of your comment (but never ever would I understand the tone) if I had mentioned other animators leaving Babitsky out, but it doesn’t mention any animation whatsoever and proceeds to talk about illustrations. If you can’t understand or accept the fact that it’s about them being anthropomorphic mushrooms, more than them being dancing, it’s entirely your own business. You brought dismay and sadness into my day, under a post that was born to show some pretty things to a depressed friend and lully her through a night of quarantine. You are not welcome here: see yourself out.